(Part 3 in a series)

by Todd Wilkinson

Eastward, just across the narrow Gallatin Mountain Range from Big Sky, is Park County, Montana where, as mentioned earlier in this series, county citizens were going to the polls on June 4, readying to vote on whether to repeal their county growth management plan. The issue had been contentious, as most planning-related issues in the rural West are, and no one knew for certain what the outcome would be.

On June 5, 2024, results were announced: Sixty percent of Park County residents rejected the initiative put forth by libertarian, anti-regulatory interests who had long held sway in the county and who bristle at planning that comes with enforceable zoning. The majority of voters, deeply worried about sprawl, claimed a victory while breathing a sigh of relief. The triumph, however, was temporary.

It didn’t take long before Park Countians realized again that, no matter which way the expression of participatory democracy had gone, growth issues are still bearing down on their special province the same they are in every Greater Yellowstone county encircling Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. In the previous installment of this series, readers learned what is happening at Big Sky amid a mostly laissez-faire approach to planning and development—development where there is no municipal government oversight and where two counties, lacking a cohesive growth plan to implement and enforce, often act largely in deference to developers. Big Sky is what happens when long-term wildlife and ecological protection is trumped by short-term economic interests.

° ° ° °

Friends of Park County and another group, the older Park County Environmental Council, have been among a small handful of local grassroots conservation organizations in Greater Yellowstone intimately involved with planning and zoning issues. There is no such group in Big Sky or Bozeman. Friends of Park County has cultivated a feisty reputation for bluntly pointing out things about the pace of change occurring there that other groups would rather not hear.

Wild public landscapes in Greater Yellowstone have never been protected through soft or voluntary approaches to conservation but rather through making hard decisions, passing legislation and having environmental protection laws backed up in court if necessary. Private land protection, in contrast, has been a different kettle of fish, one in which national environmental groups, synonymous with public land issues, have avoided.

Private individuals can make a huge difference in advancing landscape conservation. The best example is that of John D. Rockefeller Jr. who, a century ago, quietly purchased private ranches from willing sellers in Jackson Hole then deeded the land to the federal government to create what is today Grand Teton National Park. Despite local rancher Clifford Hansen, as a young Teton County commissioner, leading one of the first “sagebrush rebellions” in the West to protest what Rockefeller did, he later had a change of heart. Hansen would go on to be governor of Wyoming and serve the state as a US senator. He and others predicted economic calamity if private property was shifted into the hands of the federal government with protected status. Yet in the latter years of his life and as the value of his own private ranch land soared, Hansen told me in interviews that what Rockefeller did, expanding the boundaries of Grand Teton and safeguarding the floor of Jackson Hole in front of the Tetons from sprawl, was the best thing that ever could have happened to the valley.

Not only was the “spirit of place,” a term invented by noted Jackson Hole conservationist Olaus Murie secured in a way that would transcend time, but conservation in the northwest corner of the state is one of the most dependable, sustainable drivers of Wyoming’s economy. The irony is that conservation also has been a de-facto insurance policy for protecting property values on adjacent private land.

When it comes to conservation, businessman Ted Turner, who founded CNN and transformed the face of modern media, he had a different approach in mind than Rockefeller. Turner believed that the private sector, working to advance environmental protection and public good, can achieve the best outcomes faster, better and cheaper than government. After Turner purchased the 113,000-acre Flying D Ranch outside of Bozeman in the late 1980s, he worked with The Nature Conservancy to put a conservation easement on the property to protect it from development. It was then one of the largest such easements in the country. Some in Big Sky looked at Turner and thought he was crazy.

Had Turner wanted, he could have easily instead exploited weak planning regulations in Gallatin and Madison counties. He could have subdivided the Flying D, which stretches from the banks of the Gallatin River on the east to the Madison River on the west, and sold thousands of lots, yielding trophy homes, luxurious guest lodges, golf courses, spas and landing pads for helicopters. For his initial investment of $22 million, he could have netted billions.

Turner and Blank, like the Rockefeller family before them, are different kinds of thinkers who demonstrate the meaning of true ecological sustainability, holistic thinking and taking action to enhance the best stewardship outcomes for wildlife and people who value it. But they don’t have the resources to buy up and protect all of the private rural land vulnerable to sprawl around them.

When I interviewed Turner for my book Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet, he said, “Why would I want to do an idiotic thing like that? Instead of that, there is this.” Today, in addition to his bison, he shares the land with public elk, pronghorn, mule deer, moose, grizzly and black bears, mountain lions, imperiled westslope cutthroat trout, dozens of other species and, notably, one of the largest wolf packs in North America. He views saving the Flying D, part of which the public can visually enjoy while driving a county road leading to Spanish Creek Campground, as one of his proudest accomplishments. Turner is considered a hero to people of the Gallatin Valley. “How we take care of the land,” he told me, “is our legacy.”

In Paradise Valley, fellow Atlanta businessman Arthur Blank, who founded Home Depot and owns professional sports teams, shares the same conviction as Turner. Blank owns four large ranches in Park County and he, too, has put much of his holdings under conservation easement. He could have behaved like the powerful villain developers portrayed in the TV show Yellowstone and realized quadruple-digit profits by slicing them up into ranchettes and invoking the excuse, “Well, if I don’t do it, somebody else will.” But Blank, like Turner, enjoys being able to move freely around southwest Montana and not be cursed by locals for destroying the sense of place he shares with them. He too is praised for doing something that, in perpetuity, will enable the trove of wildlife in his part of Park County to migrate seasonally between essential habitat, which means bettering the animals’ chances of survival.

Turner and Blank, like the Rockefeller family before them, are different kinds of thinker capitalists who demonstrate the meaning of true ecological sustainability, holistic thinking and taking action to enhance the best stewardship outcomes for wildlife and people who value it.

But generally, as the record shows, people like Turner and Blank are unicorns. In addition, they don’t have the resources to buy up and protect all of the private rural land vulnerable to sprawl around them. This is where citizen-supported planning and zoning in the counties of Greater Yellowstone comes in. What it does is put limitations on property owners who are captive to short-term thinking, interested in turning quick profits to satisfy investors, and who don’t value the extraordinary concentration of large mammalian biodiversity that exists here and only a few other places on Earth.

On June 4, 2024, Park County residents (only county residents could vote; people in Livingston could not) voted convincingly to reject an attempt to repeal the county’s existing growth management plan. In an all-important related measure, they also passed a referendum requiring that regulations in the future in Park County be approved by voters and not enacted only by the county commission.

Soul-searching in Park County about what residents want their county to be—and look like—in another generation has only begun. As mentioned in the first installment of this series, the crucial question is not merely if citizens value wildlife and pay lip service to protecting open space and maintaining rural character, but what are they actually willing to do about it? The Park County Community Foundation is at the center of an ongoing conversation happening through its “We Will Park County” campaign. It focuses on five key areas that are inextricably interconnected: landscapes and natural amenities; small town and rural lifestyle; economic performance; housing and affordability; and health, safety and education.

° ° ° °

Two years ago, Friends of Park County commissioned a scientific poll that illuminated how important wildlife is to county residents. Not surprisingly, only 10 percent of respondents thought natural beauty and wildlife were insignificant contributors to local quality of life. If oldtimes and newcomers are not totally aware of what resides in their wild backyard, here is a reminder. References to Park County’s world-class biological diversity were earlier highlighted in a document called the 2013 Park County Atlas that was a collaboration of local government and conservation/community organizations. Its contents offer fodder for Park County residents to consider how they might might think differently were wildlife, often taken for granted, to vanish or become so marginalized by the trappings of sprawl as to disappear This fact is what gives them bragging rights. Park County itself, and like nearby neighboring counties in Greater Yellowstone, holds more native large mammal diversity than 95 percent of the hundreds of other counties in the West.

This fact is what gives them bragging rights. Park County itself, and like nearby neighboring counties in Greater Yellowstone, holds more native large mammal diversity than 95 percent of the hundreds of other counties in the West.

The Park County Atlas provided a short overview of some of the many wildlife superlatives: the Shields Valley and Crazy Mountains have an unusually high concentration of golden eagles, one of the best-preserved native Yellowstone cutthroat trout populations in the state, one of the largest mountain goat populations in the Lower 48, along with more than 1,500 pronghorn and several thousand elk that can still move because their migration corridors are not blocked.

South of US Interstate 90 as one moves closer to Yellowstone Park where the county border ends, Park County has even more wildlife that move through its open spaces on public and private land, including species that are very rare or absent in the rest of the country outside of Alaska—grizzlies, wolverine, lynx, as well as bighorn sheep, Yellowstone bison, moose, pronghorn, and elk.

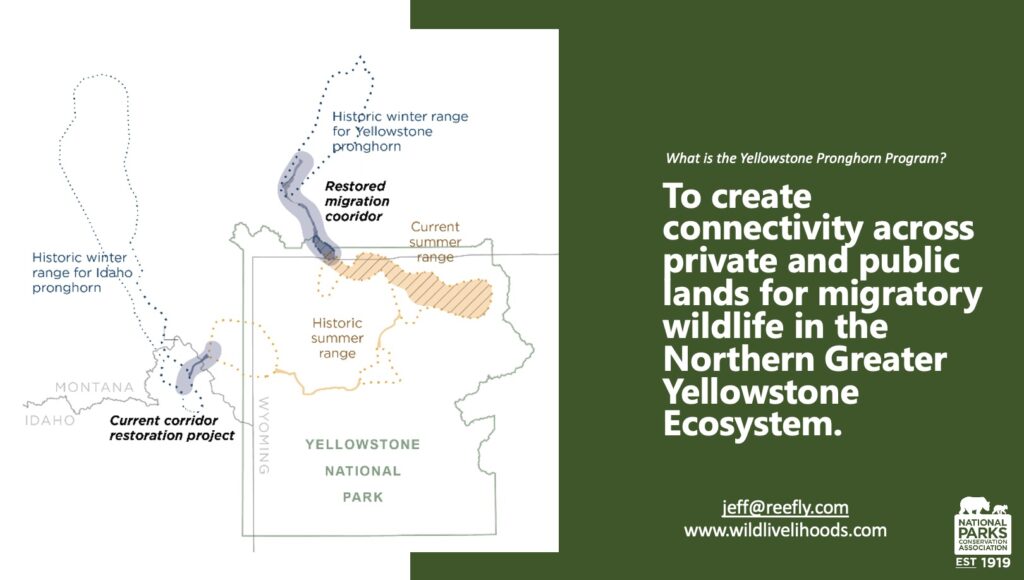

Conservationists groups like the National Parks Conservation Association, individual citizens like Jeff Reed and members of a group, Wild Livelihoods, are working with government agencies and landowners in areas just to the north and west of Yellowstone to try to save the tiny scattered pronghorn population in Yellowstone whose migration routes have been partially blocked by development. Whether those efforts succeed, and whether the seasonal ranges of pronghorn can be expanded depends largely on what happens on private lands in Park, Gallatin and Madison counties in Montana and Fremont County in Idaho.

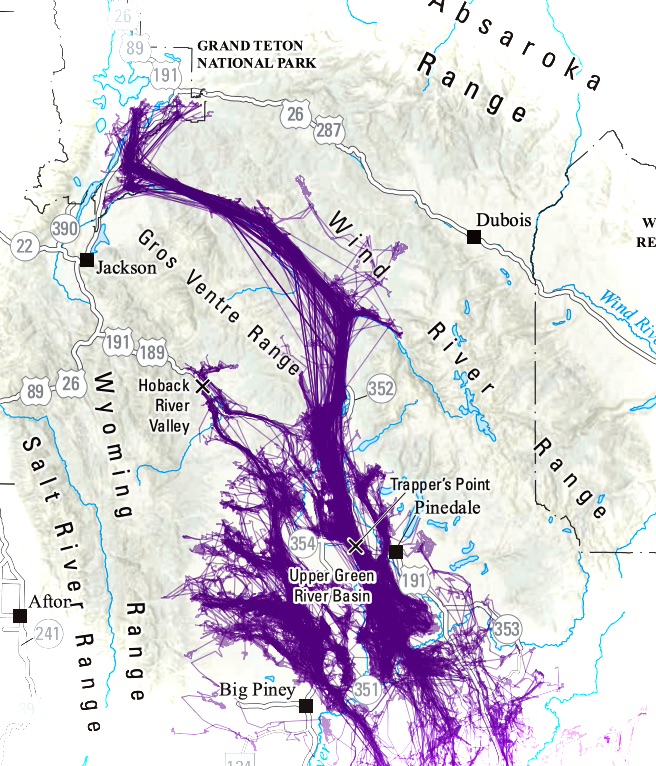

Pronghorn, often overlooked in Yellowstone and Grand Teton parks’ parade of charismatic megafauna, are an indicator species and their plight foreshadows potential future problems for wildlife. Like pronghorn in Wyoming that follow the high profile Path of the Pronghorn migration route between Grand Teton National Park in Jackson Hole and the Upper Green River Valley/Red Desert to the south, many members of Park County’s much smaller and more isolated herd move between Yellowstone and Paradise Valley, part of a migration that since the end of the Pleistocene extended further onto the prairie.

Wyoming Game and Fish is the unrivaled national leader, among all state wildlife management agencies, in working to protect migration corridors. Although it has come under withering criticism for its approaches to managing wolves and grizzly bears, and feeding elk in a time of increasing worry about Chronic Wasting Disease, Game and Fish, working closely with the Wyoming Migration Initiative and independent scientists, has engaged the public and been direct in raising concerns about threats to corridors. From its director to field personnel, people in the agency are pioneering new thinking about keeping biological linkage zones viable and making their own commitments to Greater Yellowstone’s legacy as the cradle of American wildlife conservation.

The impact of energy development in the Upper Green River Basin of Sublette County near Pinedale and near the foothills of the Wind River Range has been well documented in its effects on pronghorn, mule deer and greater sage-grouse. In a published evaluation of habitat threats in Sublette County, Game and Fish scientists recently pointed to deepening concerns about sprawl and residential development.

So that readers here get the full gist of what the agency stated in its 2024 report, read the following verbatim analysis. A similar narrative can be applied to Montana’s Paradise, Madison, Shields and Gallatin counties, as well as Fremont and Teton counties in Idaho, in particular sprawl spreading through Island Park and the flats around Henrys Lake/Raynolds Pass that is a crossroad for pronghorn, elk, mule deer and other species moving between Yellowstone Park on the east and the Centennial ValleyGravelly Range on the west.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

“There are several significant threats to maintaining the functionality of the Sublette antelope herd’s seasonal movements. One of the most pressing threats is habitat loss associated with the expansion of suburban development and general expansion of the human population into native habitats. Subdivisions and associated disturbance from roads, fences, pets and humans have already affected the functionality of the corridor in some areas, and demand for more development continues to be a pressing concern.“

—Report from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Wyoming Game and Fish’s assessment of dangers to Sublette County’s pronghorn, including animals moving seasonally between Grand Teton National Park and the Upper Green River Basin, reads: “There are several significant threats to maintaining the functionality of the Sublette antelope herd’s seasonal movements. One of the most pressing threats is habitat loss associated with the expansion of suburban development and general expansion of the human population into native habitats. Subdivisions and associated disturbance from roads, fences, pets and humans have already affected the functionality of the corridor in some areas, and demand for more development continues to be a pressing concern. Recently, the influx of people relocating to western Wyoming has greatly increased, likely fueled by the Covid-19 pandemic and the increased ability for employees to telework away from urban centers. As of 2021, the total population of Sublette County has increased 78 percent since 1990 and 46 percent since 2000. Demand for additional residential development and changes to county zoning to accommodate this demand has occurred throughout the corridor While private land is not the dominant land ownership through the corridor, the impacts associated with this population expansion are predominantly focused in these areas. Development can disrupt migration behavior and significantly impact the functionality of the corridor by animals increasing speed of movement, reducing time in stopovers or shifting use of stopovers. The area directly west of the town of Pinedale is an example of how residential development severed a historic bottleneck. A busy roadway, numerous new buildings and impermeable fences have nearly eliminated use of this area.”

To city slickers relocating to Wyoming and even to longtime residents unfamiliar with wildlife ecology, Sublette County and big open valleys in Greater Yellowstone may seem empty; it may lead them to believe that sprawl is benign or that “wildlife just needs to adapt.” But scientists say it’s precisely this kind of naive thinking, either willfully or unknowingly promoted by developers and accepted by county commissioners and county planning staffs in granting new subdivision approvals, that could irreversibly damage Wyoming’s world-class migration corridors. They are a source of deep pride in the state. The analysis also illuminates how it really does not take a lot of development to sever a migration corridor or impair its function.

Yellowstone’s pronghorn population is a case in point. In their book Yellowstone Pronghorn: Recovering from the Brink of Extinction, lead author P.J. White, Kerry Barnowe Meyer, Robert Garrott, and John Byers take readers through the history of pronghorn presence in Yellowstone and note how two major shocks to their population—development that blocked their ancient migration route out of the park through Paradise Valley and killing by hunters—left behind small, fragmented populations in northern and western sections of the park.

During more recent times, prior to wolf reintroduction, coyotes which rose in number and filled a vacant niche after wolves were exterminated by the 1940s, resulted in heavy predation pressure on pronghorn fawns. With the restoration of wolves, coyote numbers were reduced enabling the pronghorn population to stabilize albeit at a lower level. The animals are still vulnerable to a combination of hard winters, potential disease outbreaks, predation and drought. The biggest challenge to their resiliency, however, is habitat modification and limited range at lower elevations; more precisely, a gathering gauntlet of sprawl on lands north of Yellowstone and outside the park’s western boundary in the southern Madison Valley. Restoring migratory behavior is possible but windows of opportunity could permanently close if corridors on private land outside Yellowstone get block by sprawl. It’s also possible that pronghorn once moved from Yellowstone in late autumn into the southern Gallatin Canyon and through the Madison Range, via drainages like the Taylor Fork and West Fork of the Madison, where Big Sky is now located. While the Taylor Fork still holds potential, the presence of Big Sky has likely ended that possibility forever.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The question before elected officials, citizens and landowners in Park County is: will they heed the data Reed and other scientists are producing or will they make decisions that result in these creatures winking out? Should this happen, Park County would gain dubious distinction by being the first in our era to knowingly let an iconic species disappear before its eyes.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Pronghorn are a potential harbinger and a microcosm of the challenges facing them and other migratory species. Yellowstone itself isn’t big enough to sustain an enduring pronghorn herd. On the positive side of the ledger, read a story that appeared in The Land Report about what two environmentally-minded investors, Rebecca Patton and Tom Goodrich, working with Bozeman-based Beartooth Capital, are doing to acquire and save strategic pieces of private land in the vicinity of Henrys Lake and the southern Madison Valley.

In Montana, local Park County conservationist Jeff Reed has done what many call a remarkable job tracking the movement of pronghorn in Paradise Valley where he lives. He has confirmed that sprawl is no friend to the amazing fleet-footed ungulates still holding on there. A high tech guru, he’s the bulwark behind an effort to use remote cameras, sophisticated audio recorders and AI via his private company, Grizzly Systems, to track the movements of different wildlife species. What many Park County residents don’t realize, he says, is that pronghorn movements could easily become curtailed by just a handful of poorly-sited subdivisions overtaking the remaining farms and ranches. The question before elected officials, citizens and landowners in Park County is: will they heed the data Reed and other scientists are producing or will they make decisions that result in these creatures winking out? Should this happen, Park County would gain dubious distinction by being the first in the modern era to knowingly let an iconic species disappear before its eyes.

Mule deer, also a species highly sensitive to exurban sprawl, are suffering mightily on the other side of Bozeman Pass in the foothills of the Bridger Range north of Bozeman due to intensifying rural development. Biologist David F. Pac documented the start of their decline back in the 1980s. With development now encircling three sides of the southern Bridgers, along with intense rising recreation pressure largely unmitigated by the US Forest Service, mule deer on adjacent private land are not adapting as well as weedy white-tailed have to disturbance.

If Park County is not careful, the late conservation biologist Brent Brock who studied development trends in Paradise Valley, said, the same pattern of decline could happen in the mountain foothills for mule deer there. Park County, unlike Big Sky and Jackson Hole, does not have a major downhill ski area anchoring lavish gated communities and speculative real estate involving billions of dollars’ worth of property changing hands.

But it has a lot of monetizable natural wonders that make it more vulnerable to attempts at exploitation by big developers, with huge amounts of outside capital backing them. Many outside developers find existing planning and zoning in Montana weak by comparison to elsewhere. There is the magnetic attraction of Yellowstone National Park in the southern end of the county; the Yellowstone River meandering through Paradise Valley and the mid section of the county with the Absaroka and Gallatin mountains on either side; there is the river town of Livingston that commands its own mystique; beyond that there is the Shields Valley in the northern part of the county located between the Crazy and Bridger Mountains. Finally, there is the direct spillover effects of growth coming from Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley just on the other side of Bozeman Pass along Interstate 90.

None of this is a secret; the word already is out. It’s proclaimed in multi-million-dollar promotion campaigns from the state tourism office, and the biggest blow-horn of all is the popular TV series Yellowstone that has called attention to the vulnerabilities of a fictional Paradise Valley located just north of Yellowstone Park. Not long ago, Lone Mountain Land Company purchased the 18,000-acre former Marlboro Ranch in northern Park County and renamed it Crazy Mountain Ranch. Lone Mountain is the titan of land development in Big Sky and holds title to three ultra-elite gated communities—the Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, and Moonlight Basin and it has major development plans in Big Sky’s Town Center. One of Lone Mountain Land Company’s first big maneuvers in the Shields Valley with Crazy Mountain Ranch was to break ground on a new 18-hole golf course designed by Ben Crenshaw and Bill Coore. Watch this video and decide for yourself how much thought appears to have been given to the consequences of building a golf course in wildlife habitat. Residents of Park County, seeing what happened in Big Sky, hope that Lone Mountain Land Company doesn’t bring the same aggressive style of monetizing landscapes to the Shields Valley. As of right now, the company’s future plans there are a mystery.

° ° ° °

Brent Brock loved doing wildlife research in the Madison Valley and he partnered in recent years with Steve Primm, who is an expert in rangeland stewardship, human-grizzly bear co-existence and was a co-founder of the group People and Carnivores. Brock had a special soft-spot in his heart for Park County. To save wildlife, he was devoted to finding ways of keeping working ranchers on the land and he was a firm believer that cows are better than condos. I frequently had Brock fact-check my stories to make sure I was getting the science right and he shared hundreds of research documents with me over the years.

Tragically, Brock passed away in early October 2023 at age 61, from cancer. At the time he was perfecting a computer modeling program called Wild Planner that not only innovatively plotted the impacts of existing rural residential subdivision on wildlife, but it allowed him to simulate future growth trends and draw conclusions about what it would mean for wildlife in valleys like Paradise and the Madison.

Today, several large ranches in the north-to-south trending Madison Valley are protected by conservation easements but if half of the remaining unprotected private tracts become covered in 20-acre ranchettes, then things like the Madison Valley’s spectacular elk migration comprising upwards of 8,000 to 10,000 animals and one of the largest in Greater Yellowstone—could be severely impacted. That goes for the pronghorn, too.

When people drive south on US Highway 89 from Livingston en route to Yellowstone through Paradise Valley, they see scatterings of homes along the Yellowstone River. Brock worried they might get a false impression about sprawl being a slow-moving contagion. Up many of the side drainages hundreds of homes are packed into those draws, each with their own water wells and septic systems, plus driveways, fences, horses, chickens, yard lights, barking and roving dogs, lawns, unsecured garbage cans that can attract bears and sprawl is spilling out onto the valley floor. It is creating a deadly labyrinth for wildlife to navigate which may not register to the human eye.

“What people don’t realize is the open space they see in front of them today and the wildlife moving through may be an illusion informing how they imagine the future,” Brock said. “It isn’t always going to be that way. In fact, it’s a reflection of the past. Invisible are all of the subdivision lot lines that already have been approved down at the local court house. And there could be a lot more. The problem is the public isn’t aware and the time to make important decisions to save these valleys isn’t when the bulldozers are breaking ground.”

“What people don’t realize is the open space they see in front of them today and the wildlife moving through may be an illusion informing how they imagine the future. It isn’t always going to be that way. In fact, it’s a reflection of the past. Invisible are all of the subdivision lot lines that already have been approved down at the local court house. And there could be a lot more. The problem is the public isn’t aware and the time to make important decisions to save these valleys isn’t when the bulldozers are breaking ground.”

—the late conservation biologist Brent Brock

As Brock’s own end was drawing nearer in the summer of 2023, he rallied when he should have been resting, organizing his files for Wild Planner with the hope they could be passed along to other scientists who could run the model and make the trendlines more clearly visible to elected officials, planners and citizens. What he created was an incredible, eye-opening tool and was his gift to a future he could not see but one, he hoped, could make a difference posthumously.

“I don’t have a lot of time left, but we in Greater Yellowstone don’t either to prevent the worst outcomes from happening. They are not imaginary. The good news is we can still make course corrections,” he said. “I love this place. We brought all of the major species in Greater Yellowstone back from the brink once thanks to conservation. But if we lose them this time, because of the choices we are making not to act, we won’t have that opportunity again.”

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Read Part 1: Of Gut Checks And Moments Of Truth What happens when communities surrender their wildlife to sprawl? Outside Yellowstone and Grand Teton, Jackson Hole, Teton Valley, Bozeman, Big Sky, Island Park, and Madison Valley are wrestling with the question. Nowhere does it loom larger at the moment than in Park County and Paradise Valley

Part 2: The Spillover Effects Of Big Sky’s Ravenous Appetite For More As Park County contemplates the future and ponders how it can protect its special sense of place, a major Big Sky land developer has moved into the neighborhood. A story about why ecologically-minded planning matters in Greater Yellowstone

In Part 4 we will take a look at what the compelling body of science says about the impacts of sprawl on wildlife and what it means for citizens and the counties of Greater Yellowstone.

ALSO READ:

On The Front Doorstep To Yellowstone, A Montana County Wrestles With How To Confront Change by Randy Carpenter and Robert Liberty

Can the ‘Californication’ of Idaho Be Slowed? by Rob Harding

Support Yellowstonian and

Get Some Real Cool Visual Stuff

From now through the end of July, Livingston-based Artemis Institute, the parent non profit entity of Yellowstonian, is participating in the Park County, Montana Community Foundation’s Give a Hoot fundraiser and all contributions made to Artemis Institute will support Yellowstonian‘s mission of providing conservation journalism focused on Greater Yellowstone. We would be profoundly grateful for your support and here’s your chance to get a really cool visual reward for your generosity: Anyone who contributes $35 or more will receive their pick of one individual species poster below or all three for $100. For a donation of $350 or more, supporters will receive a special, limited-edition collector’s lithograph that features all three of Greater Yellowstone’ species’s icons. It is hand-signed by Eric Junker.