by Holly Pippel

I often get asked, “What drives you, what inspires you to stop and take a photograph?”

For several years now, in this phase of my life, I’ve turned to my cameras to help interpret what I’m witnessing in the world around me, from beauty that encircles us in southwest Montana to the steady pace of change that one can see happening at nearly breakneck speed.

On any given day, I adhere to a habitat that has become a ritual. I spend five to 30 minutes in semi-wild to very wild places near my home in Gallatin Gateway, Montana. On the weekends, I tend to get out on foot and horseback for quiet time with wild things to have more prolonged remote interludes.

Semi-wild to very wild are, of course, subjective, relative terms, and for me they relate to the varieties of wildlife that reside in each setting and/or correlating to the kind of human development that is present.

Earlier this spring, I took a trip to Jackson Hole and I drove through the Gallatin Canyon, via Island Park and the pastoral Teton Valley, Idaho then up and over Teton Pass to Wilson, Wyoming only a few weeks before that crucial connector road collapsed in a landslide.

No matter where you live in Greater Yellowstone, and if your valley is undergoing huge amounts of pressure from growth, then you too are witnessing the rapid transition of wild places turning to semi-wild. The images that I’ve been amassing may have a familiar feel about them to you, too.

Below are a few instances, presented as photo vignettes, that shed light on my passion for wildlife and wild places.

Resilience

Fox kits are typically reared by both male and female parents. Not this year. The mother whom I’ve nicknamed “Stella” has been raising five kits alone. Her male fox mate, whom I called “Reynard,” has been absent since I first discovered them in early April at an old den site along the river. Nothing short of miraculous is the survival of these young ones and praise goes to the single mother. Approximately 75 percent of kits typically won’t make it through their first year. Disease, traffic collisions caused by speeding inattentive drivers, trapping, poison, shooting and predators such a coyotes make it a challenge to reach adulthood.

As of the writing of this column, all kits are accounted for and doing well. We need carnivores and scavengers contrary to some popular beliefs. Stella and her clan have put a serious dent in the gopher population near her two chosen den sites. So, if you have a fox den close to you, be curious, get informed and enjoy watching nature unfold before you. It will make your own life feel richer. Follow#foxkitchronicles2024

Hindsight

Just a month and a day before the historic 2022 flood event in Yellowstone National Park and Paradise Valley that through the sheer power of Mother Nature changed the course of rivers and people’s lives, I took this photo in the park’s Lamar Valley. What struck me then about this pair of Uinta ground squirrels, and tempted me to lay flat and still on my belly in the grass as they stood, was their expression. As they peered out across thousands of acres in the Lamar, soaking up the early morning sun, they seemed to be appreciating the same view that we were. Hundreds of bison, some with new calves, were feeding along the river not knowing that a major flood event was just around the bend. While apex carnivores are always a highlight, I am drawn to the unsung, often-underrated species in our midst. They also play an important role in biodiversity.

Patience

Motivated by the ambiance of early morning light, the possibility of witnessing quiet interactions between animals is what gets me going early before work most days. This was such a day. At daybreak in the Gallatin Valley, there were two horses on a ridge backlit as the day began to break. One horse kept looking down the ridge and running to a fence line and back several times, peering into the distance. I thought to myself, “Something special is about to happen.” As I waited patiently, I soon saw a lone mule deer approaching from the south at a steady walk. His equine counterpart seemed to anticipate his arrival and quietly waited for him to jump the pasture fence and greet him. It appeared that they were familiar with each other and that this was a rendezvous they had shared before.

It is easy to apply human reasoning to animal behavior when you spend so much time observing them. There are so many subtleties we miss as we hurry through our daily routines. Animals continue to surprise me or prove me wrong often. Moments like these are my motivation to keep exploring the environment around me.

Upstream

Spending time in nature is a but a selfish pursuit. The quiet time seems almost decadent when contrasted with the visual cacophony of sprawl engulfing many of our valleys. Most of us are unaware of what is incrementally being eroded.

This day, I perched in the tall grass watching elk around Gallatin Gateway come back to Harry’s Hill for their evening unharried retirement. Of 250 members of a local elk herd crossing an old dirt road at a steady clip, almost military in fashion, one cow elk stopped and faced west. As the herd filed by, like salmon pulsing upstream, she waited with fortitude until one specific special cow reached her. This took almost five minutes. They greeted one another with nose bumps then joined the rest in a steady climb upwards to the sheltered forested hillside. I have witnessed so many interactions of individuals displaying recognition of family members and searching for one another. Not always apparent, cow/calf type interactions are more common. Such subtleties are what keeps me curious and grounded in the sense of place that exists. I want to know more about the wildlife that shares our space, visually and audibly, rightfully so; it’s their home, too.

Medieval

Once you immerse yourself in wild places, you begin to recognize the body language and habits of individual animals—their travel patterns, nuances, challenges, family units, intelligence, sense of humor and duty exhibited by elders to young. Spending time with wolves brings all of this to the table. For a couple of years, I have watched the alpha male of a pack on private land navigate seasons with all the challenges—natural and human that come with them. What he didn’t prepare for was a snare set on neighboring property.

Snares are indiscriminate killing devices; they can just as easily catch someone’s dog as they can a wolf or coyote. No livestock depredations linked to this wolf, he was the patriarch of generations and killed, for what? Wise and older, able to guide the younger members of the pack to natural hunting areas, teaching them by example, and keeping them on the straight and narrow, wolves do, outside of protected areas like Yellowstone or even private land where they are welcomed, often navigate a narrow line of survival. Who will guide the pack now with all of his accumulated knowledge gone?

The ongoing presence of snares and other forms of “predator removal techniques” are a reminder that we continue to live in the Dark Ages in which archaic thinking of the past is being applied to an era in which wildlife alive holds far more worth than a dead animal. There are sound tools now that enable landowners to use non-lethal techniques and ranchers are compensation for livestock loss. Potential livestock losses to native carnivores should be considered part of the cost of doing business when raising cattle on the fringes of wild Greater Yellowstone just as they do for loses due to frostbite, miscarriage, eating poisonous weeds, disease, breaking limbs in rugged terrain or just disappearing. Last year, I was shocked and dismayed to learn that chasing carnivores with motorized vehicles until exhaustion and then running them over until dead is legal in some Western states. And then, earlier this winter, the notorious wolf incident involving a snowmobiler happened in Wyoming.

We need to do better. While I grateful respect and praise large landowners that keep large parcels together, this doesn’t justify barbaric wildlife practices, unsafe, wildlife-unfriendly fences, snaring and poisoning. There are resources available to mitigate loses which doesn’t necessitate their use.

We need food, we need clean air and water, viewsheds, habitat for us, the same as wildlife do. We are capable of demonstrating tolerance and compassion. Education is key to having a sustainable, healthy landscape for all. Carnivores play a vital role in the equilibrium of life in Greater Yellowstone. Now is the time for us to come together in recognition and protection of the things that set this region apart.

Just because we can be cruel, doesn’t mean we should.

Flight School

Northern harriers are some of the most interesting and curious raptors on the landscape, in my opinion. The males, which are grey a.k.a. the allusion made to them as “grey ghosts,” can often have up to five mates during a season. They are one of the only raptors to be monogamous or practice polygamy. Their owl-like facial disc directs sound to their ears which is their primary hunting skill. They are year-round residents in Greater Yellowstone. How many of you have seen one?

I was fortunate to watch five young birds at the end of the summer on the precipice of a ridge practicing their hunting skills. Their practice medium of choice that day: dried bison poop. The headwind was strong as a weather front was coming in which made them unaware of my presence. Repeatedly, the young birds took turns dive bombing each other and carrying their prize in their talons as they would prey. I felt a bit like a voyeur, stealing something as I watched them hone their skills for 45 minutes utterly entranced. Once they discovered they were being watched, they took flight and disappeared over the ridge.

In the Crosshairs

Nothing gives you more perspective on the change that’s happening than being high in the air above the Earth below. As I flew out of Bozeman to Phoenix to see family, I was taken aback by the stark symbolism beneath me on the valley floor, set in the shadows the Bridger Mountain Range. The farm ground was delicately carved with a perfect bullseye—timely, as Bozeman and the ever-important outer reaches of the valley are bursting at the seams with new growth and no comprehensive plan on the books. Literally, rural farms have a target on them by developers of all kinds.

Wild places, possible wildlife connectivity corridors and scenic vistas are being gobbled up by local landowners selling to outside investors without satiation. Billboards are popping up along US Highway 191, the historic gateway to Yellowstone—a form of tone deaf advertising that seems obvious to vocal concerns of locals who have are having unwanted change foisted upon them. How many more places to shop or eat or engage in manufactured playgrounds that could just as well be anywhere else do we need? Billboards are littering our scenic road corridors and valleys and they’re even sources of light pollution. Seriously, how much more stuff do we need, how many more natural resources do we need to extract when there is so much irreplaceable beauty? How many reminders to carry out more commerce? This image from the air was so powerful and it spoke a truth about how so much of what we love being here is now hanging in the balance.

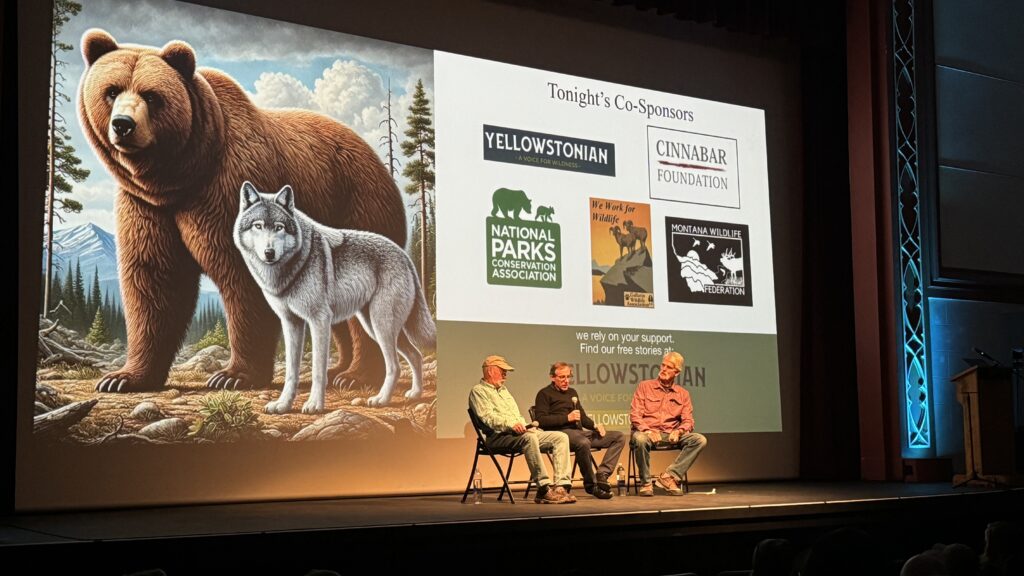

Support Yellowstonian and

Get Some Real Cool Visual Stuff

From now through the end of July, Livingston-based Artemis Institute, the parent non profit entity of Yellowstonian, is participating in the Park County, Montana Community Foundation’s Give a Hoot fundraiser and all contributions made to Artemis Institute will support Yellowstonian‘s mission of providing conservation journalism focused on Greater Yellowstone. We would be profoundly grateful for your support and here’s your chance to get a really cool visual reward for your generosity: Anyone who contributes $35 or more will receive their pick of one individual species poster below or all three for $100. For a donation of $350 or more, supporters will receive a special, limited-edition collector’s lithograph that features all three of Greater Yellowstone’ species’s icons. It is hand-signed by Eric Junker.