by Steven Fuller

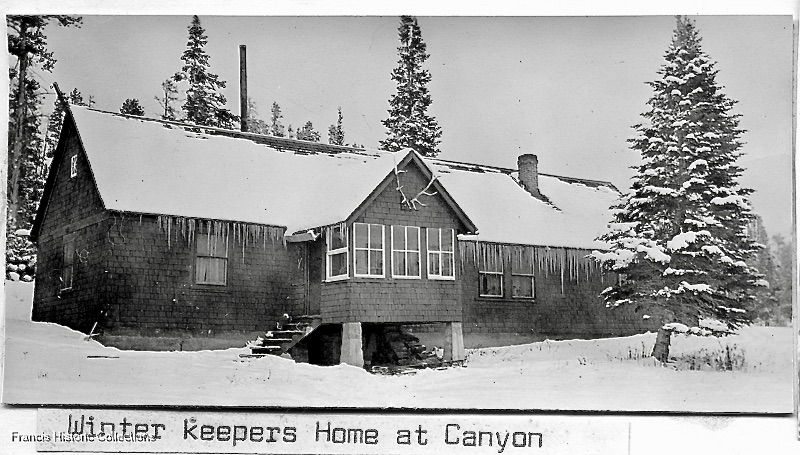

My first sight of the Canyon Village winterkeeper’s house was on a raw gloomy afternoon in late September, now more than fifty years ago. My English wife, Angela, toddler Emma, and my latter twenty-year-old self parked our $100 car in the black cindered wasteland in front of the house and went inside.

I had been hired the week before by “YP Co.,” aka The Yellowstone Park Company as the next winterkeeper for the winter of 1973-74. I would be the solo caretaker of Canyon Village, a summer tourist complex located near the center of Yellowstone National Park. The care of the Village, they said, was now in my hands.

The pay was $13.25 a day but included the house and utilities. I was the only applicant for the job which was the only reason I had been hired.

The need for a keeper was critical and the onset of winter impending and so, given that the company had no other option, I was it.

Inside, the kitchen included a kerosene-powered refrigerator similar to the one I had lived with for two years in East Africa—three classic i.e. “old” chest meat freezers (indicative of the culinary preferences of my predecessors), and several curious retro-vertical cylindrical propane heaters to heat the house. Even in 1973 it was a visit into the past.

The furniture was a hodgepodge of musty overstuffed chairs salvaged from the Canyon Grand Hotel built in 1910 and a poorly-patched orange vinyl couch, circa mid-1950s, discarded from the historic hotel’s successor Canyon Village, located a mile to the north of our house and opened to visitors in the summer of 1956.

Later, I learned that the Grand Hotel, a rambling structure a mile in circumference and designed by Robert Reamer, had stood downslope of the winterkeeper’s residence until it was condemned by the park authorities as obsolete and burned in 1959. It was a circumference that, in time, I came to appreciate as its absence much improved the extraordinary view overseen by what became our, then later, my home, where I am today writing these words.

Our casual walkthrough of the house was unlikely to have found the accommodation unsatisfactory, as it was a great improvement over our yearlong hardscrabble attempt to pioneer a sustainable life in Wyoming and Montana. Under the circumstances we found the house to be acceptably rustic. I was especially pleased with the pencil sharpener attached to the kitchen wall, an accoutrement that portended a more settled life.

We moved in on October 1, 1973. After years of wandering I knew I had found the place for which I had been searching.

A few days later I was given an “orientation,” a day with my predecessor, a local who lived distant but who had spent the two previous winters as the Canyon keeper. Our initial conversation set out the “expectations and challenges” that came with the job. The words used then were earthier and franker than those I quote above.

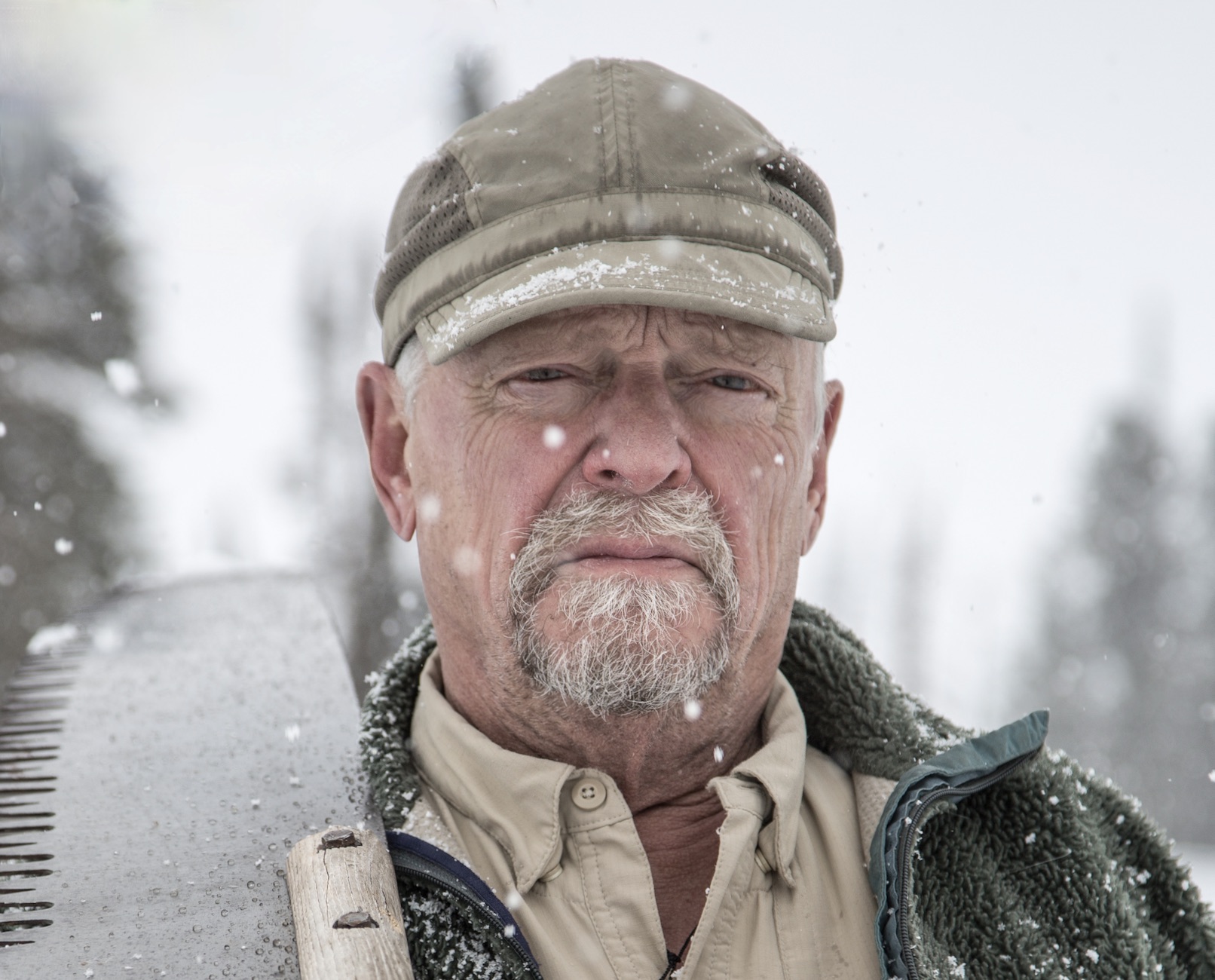

In those days the job was a hardship posting; a winter solitaire, remote, poorly-paid, mentally testing, and if undertaken conscientiously, physically grueling. He didn’t explicitly share these facts with me, but similar to mining, logging, and ranch labor work of the times, there was not the slightest hint of romance for what I had signed up to do.

To the locals the job was a last alternative because winter work in the two small gateway towns West Yellowstone and Gardiner, Montana, each 40 miles away from Canyon, was near to nonexistent.

My calloused tutor told me that winterkeeping was simple— to keep enough snow off the flat roofs of 60 eight-plex cabins, four dormitories, the main lodge, and sundry other buildings so that nothing broke, or worse, collapsed under the winter’s snow load of hundreds of inches.

He told of the short timer winterkeeper before him who had been fonder of whiskey than shovels and due to the damage to several of the buildings had been fired the following spring. I took the story as a warning.

In a back shed he showed me the tools of my new trade: a half dozen D-handled steel blade coal shovels, two six-foot snow saws, and a wood extension ladder. For fall protection on the high roofs I was given a leather waist belt with a D-ring (but no rope) and finally the pièce de résistance, an archaic worn out Johnson snowmobile.

In the course of the day, as we became better acquainted, he shared how to poach one of the several mule deer that wintered close by and, as an afterword, revealed that his predecessors had trapped pine martens and sold them to fur buyers outside the park so as to subsidize the poor wages that came with the job.

In the course of the day, as we became better acquainted, he shared how to poach one of the several mule deer that wintered close by and, as an afterword, revealed that his predecessors had trapped pine martens and sold them to fur buyers outside the park so as to subsidize the poor wages that came with the job.

Later, in the crawl space under the house, I came across several deer legs, presumably those of the victim of a previous “poaching for the pot” and a couple of leg traps, likely for coyotes.

He told me our nearest neighbors were at Lake Yellowstone, 18 snowmobile miles to the south. They included a ranger and his wife and two winterkeepers tending to the Lake Hotel and Lodge and its cabins. One of those winterkeepers was a widower whose wife had died there during a winter and the second a fellow known as “Silent Joe.”

I never met him.

Any visit to our closest neighbors would require an overnight stay and thoughtful consideration of weather and trail conditions for the snowmobile trek southward through Hayden Valley where wind- blown snow created a formidable albino dunescape of drifts.

In those early days there were no other people nor amenities at Canyon, no ranger, no gas station, no warming hut. The occasional adventurous, most all of whom were regional snowmobile enthusiasts, were on their own in here which was one of the reasons we always left a light on in our front window. We attracted a few unfortunate pilgrims to whom we were able to give shelter when late in the night they hammered on our door.

If the Lake tribe didn’t suit our social needs, our other options were the two distant gateway towns, both reachable only by snowmobile. However, YP Co.— my employer—had made it adamantly clear that once snowed in we were not to leave Canyon until the snow plows liberated us come April.

On our walk around the outside of the house I noticed that the exterior of the back door was pieced with scores of prominently protruding nail points.

“Why?” I asked?

“To prevent grizzlies from tearing the door open,” he replied.

“Hmm…,” I said.

A year later, Guy Fawkes night November 5 [a British holiday we appreciated due to Angela’s nationality and to my previous times immersed in various iterations of the British diaspora], an elderly sow grizzly broke in the kitchen window while we were eating dinner and took a pot of stew off the stove.

In time, as the years passed into decades, this experience and a myriad of others came to populate my consciousness and eventually to meld into an amalgamation of self and place. Early on, I came to love the unpretentious house and its intimacy with the extraordinary landscape in which it had come into being.

In time, as the years passed into decades, this experience and a myriad of others came to populate my consciousness and eventually to meld into an amalgamation of self and place. Early on, I came to love the unpretentious house and its intimacy with the extraordinary landscape in which it had come into being.

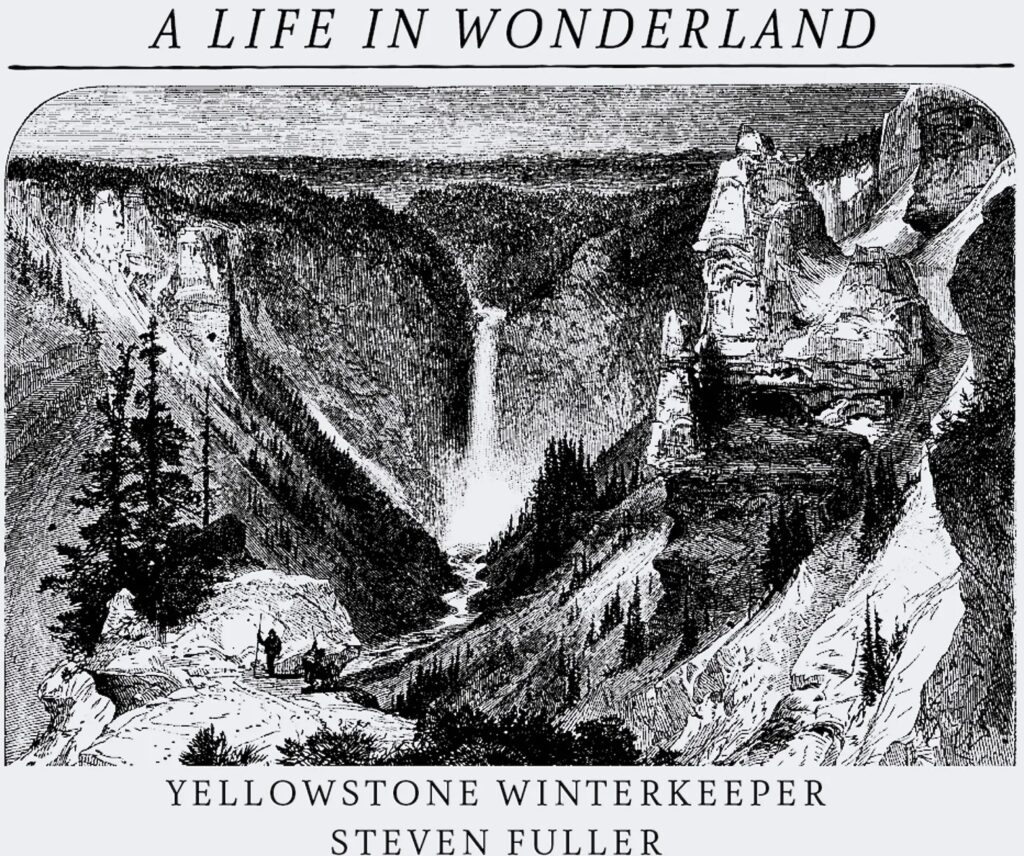

The house overlooks a fringeof lodgepole pine trees that conceal the northern rim of the narrow gash of the Yellowstone River canyon here 1200 feet deep. The gorge bisects a basin of steaming geysers hot springs and fumaroles that have hydrothermally metamorphosed the complex geological stratigraphy of the canyon creating an incomparably rich pallet of alchemic earth colors on its’ time sculptured walls.

At the head of the canyon, directly below the house, the river falls off a 308-foot cliff creating a water fall that frequently generates a column of vapor that rises high into the sky, “A Smoke That Thunders.” The plume is often back lighted, illuminated by the early morning sun or by a rising full moon. All and all, when the myriad constituents come together the spectacle is an incomparable sight to sit and to see.

And so here I sit, almost fifty-two years later, come nearly full circle, mindful of each remaining day of this, my last winter. This evening, as the sun nears the horizon, I sit on the bench bundled up outside the front of the house with my companion cats’ their pussy toes tucked under against the cold. They sit a few feet away their ears erect targeted on the rustlings of a variety of subnivium little rodents who are inaccessible, protected by the overhead several inches of a sun/cold combo of metamorphosed snow.

So far, in the course of this years’ autumn and early winter very little snow has accumulated so the meadow I oversee is a patchwork windrow of sun cured grasses and old granular snow punctuated by the standing skeletal stalks of desiccated meadow plants.

Since the snow is old it holds a cumulative record of the many animals that have passed through this past week, a comprehensive clutter of the spoor of buffalo, elk, coyote, mule deer, fox, ravens, mice, pine marten and others more mysterious.

I sit within the large matrix of a quiet surround solaced by the familiar muffled roar of a second 100-foot-high companion water fall that lives a mile further upriver at the mouth of a natural Yellowstone river canyon megaphone that points directly at the front door of the house where I sit.

When the atmospherics are just so I can uncannily hear the riffles, as if they were close-by, in the pool just below the falls. Under these just so conditions were there a water ouzel in the plunge pool I fancy I would hear the medley of its’ song and the splashes as it dips, a feathered submersible, in and out of the water.

Sit and listen. Turn down the inner voices, the maelstrom of white noise…recall the diminishing sound struck on a Zazen bronze bell that in time diminishes to zero and takes self into a new space where the ever-moving dwindling sun light on my overseen home valley is subsumed by growing shadow. Feel the swell of breeze that touches a windward cheek.

Notice a passing raven who animates the canyon and draws attention to a waxing moon and to a scattering potpourri of light catching clouds. Follow your eyes to the static reef of steam that hangs over the Crater Hills geyser in the mid distance and to a more complex bank of steam above mud volcano eight miles further south.

Understand a wisp of vapor that distracts when it appears from up out of the canyon in the foreground, a reminder of the waterfalls below. And most distant, eye ramble to the Absaroka mountain peaks that jut above the horizon at the eastern edge of my small Yellowstone world.

The surround landscape wherein I be is rich beyond notice, a myriad of details beyond any useful waste of words.

While we sit the light wanes and gradually the day world disappears into darkness allowing the stars to emerge. The temperature continues to fall and so the cats agree it is time to go inside.

ALSO READ: How Not To Love Yellowstone To Death