Ask yourself: what makes something—anything—sacred?

For the sake of argument here, also consider this question: Why don’t we treat the daily miracles of Nature with more sacred reverence, considering they are what sets life on this spinning rock apart from any other known places in the cosmos? And without many of the intrinsic things, on which the mavens of free-market economics are not able to ascribe a value, we would perish and the quality of life would be eminently poorer.

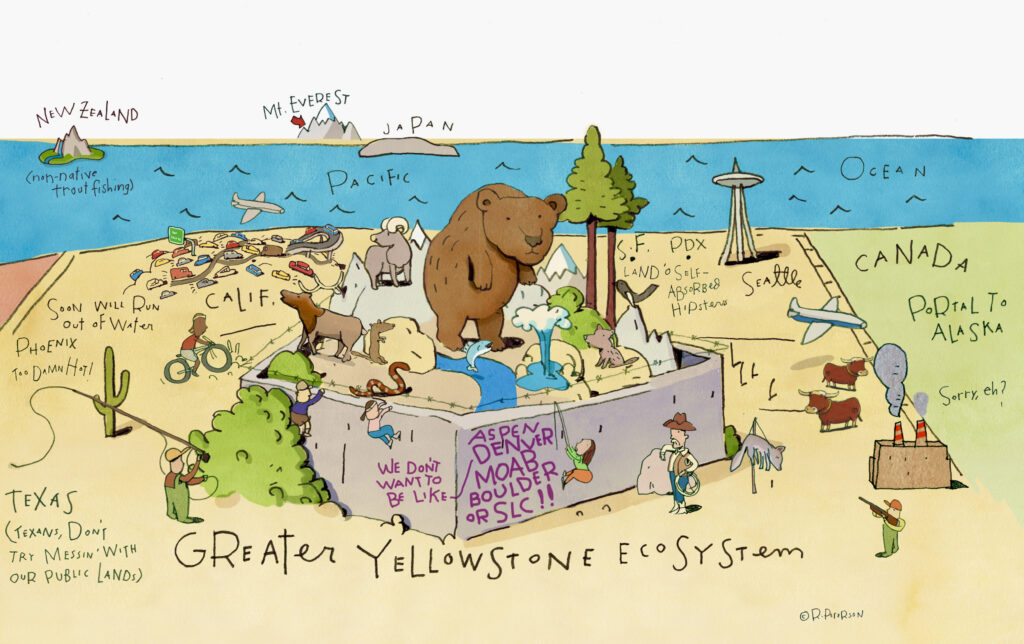

By one definition, sacredness can be applied to “objects, places and people considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion.” Another reference is to things “that inspire awe or reverence among believers.” They all exist in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

This new conservation journalism website is devoted to those who believe in the power of Yellowstone and all of its physical, biological components that extend far and wide across a larger region. Yellowstonian will be a voice foremost for the living things that call it home and we will keep exploring how the idea of Yellowstone, this first wildland nature preserve born in 1872, has evolved in its significance over the years.

In order to appreciate something that is extraordinary, priceless, irreplaceable and sacred, it might be helpful to first entertain a counterfactual reality, as in: What if Yellowstone and the influence it commands around the world, as a centrifugal of anchor our region, did not exist? If you sit with this thought for a minute, and let it percolate into your brain and heart, it really does dramatically alter the way we conceptualize the value of conservation in the 21stcentury.

For those who care about Nature, it creates a feeling of being lost and without a compass.

In its day, the creation of Yellowstone was viewed by some as an extreme and radical maneuver but today it’s an extreme and radical thought to imagine its absence. Were the US Congress and American people presented with similar circumstances in 2024, as they existed in the early 1870s, would decisionmakers now have the will, the courage and the vision to create Yellowstone again? For, without Yellowstone, there would be no Grand Teton, no national forests or national wildlife refuges, no Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. And, by extension, we may not have any grizzly bears, wolves, bison, elk, trumpeter swans, black-footed ferrets and other species left. Most of the West as we know it today would instead be privatized and colonized.

Yellowstone was a bold, rare expression of human restraint and today that’s exactly what is required to preserve the larger ecosystem bearing its name.

° ° ° °

Six months ago, while the concept of Yellowstonian was only in early gestation, I was far away from this sweet home ecoregion strolling through the streets of Ravenna in northeastern Italy near the Adriatic Sea. It was a time of much-needed and long-overdue decompression after spending six and a half years founding and then building a different online journalism site into a venue that earned a massive audience.

The rigors of that multi-tasking endeavor, however, had left me burned out, disenchanted with many frustrating aspects non-profit world. While in Ravenna, I stood alone bathed in fading afternoon light at the doorway of Dante Alighieri’s tomb (see photo). Dante, if you know history, is credited with being the godfather of the modern Italian language. His book, The Divine Comedy published in 1321, is a long-verse poem that explores the human soul’s journey through hell, purgatory and heaven.

Ravenna is famous for its artisans who turned tiled mosaics into masterpieces and for its early Christian Byzantine architecture, both of which converge breathtakingly inside Basilica di San Vitale. Enter, and it’s not just one image that evokes awe in a way words cannot describe, but rather the entirety of the panoramic experience that encircles San Vitale’s worship area.

Step back and medleys of color, pattern, texture and narrative appear. Venture closer and what you discover is that those scenes are comprised of a million individual pieces of tile and glass, many no larger than a thumbnail that have been intricately configured, one by one, ingeniously.

Imagine now, in the context of the American West, the stunning mesmerizing beadwork inlaid into the leggings of an living fancy dancer, except that the mosaics at San Vitale cover thousands of square feet of wall space rising a few stories tall. For a long stretch of time, I sat on a bench in the basilica, neck craned, mouth agape, immersed in peaceful quietude peering upward at the sanctuary ceiling. Not unlike countless moments in the backcountry of Greater Yellowstone.

Although I had San Vitale to myself, others throughout the ages had been there before. One of them was legendary art critic Bernard Berenson. He divided fine art paintings and visual media into two categories: those that he dubbed “life enhancers” and those that were “life diminishers.”

“Miracles happen to those who believe in them,” Berenson once observed. He also said, “From childhood on I have had the dream of life lived as a sacrament…the dream implied taking life ritually as something holy.” And he said, “Between truth and the search for it, I choose the second.”

We do too.The wild nature of Greater Yellowstone is life enhancing; those things taming it, abusing it, replacing it and ultimately making it go away are life diminishing.

Moreover, Greater Yellowstone is a miracle, a masterpiece that belongs to us all and which is the result of previous, forward-thinking generations. It is a lot like the spectacular interior of San Vitale yet it spans the intersection of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho. Like Dante giving Italians a common language, Yellowstone is the bedrock of the way we as a species have come to conceptualize and think about the true meaning of conservation.

The ecosystem’s centerpiece, Yellowstone, is, when you see it as more than a tourism cliche, the closest thing our country has to a shared national nature preserve considered sacred. To grasp the deeper context, it’s important to behold both a macro and micro view of how all of its pieces—from microbes in a Yellowstone hot spring to bison descendants that are survivors of biocide, from a healthy trout stream to the wanderings of a mother grizzly bear and cubs—fit together and intertwine, enabling us to grasp a larger, more holistic picture.

Yellowstone isn’t a religious place; it is, however, a sweep of Planet Earth that is full of innate spirit and magic. You don’t need to explain its sacredness to a traditional indigenous elder. It’s not difficult to gander across one of its geothermal basins at dusk and believe it possesses otherworldly mystical qualities. It’s not obtuse to gain a sense of why Yellowstone is a destination for human pilgrimage when one joins thousands around Old Faithful waiting in anticipation for an eruption; or venturing to Artist’s Point and hearing the vibrating roar of the Lower Falls thundering into the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River and not seeing the rim lined with condos and trophy homes.

Greater Yellowstone still exudes all of the essential ingredients to spark our appreciation for wildness as a reality, not as a fever dream of the Anthropocene. (Admittedly, it’s a bit harder to undergo a transformational awakening, as Paul allegedly did on the road to Damascus, when you’re stuck in the gridlock of a bison jam, but that is not what the essence of Yellowstone is.

° ° ° °

Like Basilica di San Vitale and neighboring holy places, Yellowstone is a World Heritage Site except that it is the mother of all national parks. While Dante’s tomb causes us to reflect on the past, Yellowstone should compel us to consider the future. Our survival—and the health of Greater Yellowstone— depends on our ability to be smarter with how our species fits into the larger fabric of nature. A word like the Anthropocene suggests we actually aren’t doing a very good job at exhibiting restraint or controlling greed because our conquest of nature continues at a pace that will leave wildness exhausted—unless we change our attitude.

Sacredness involves wanting to belong to something bigger than the mere worship of self or the almighty dollar. Frankly, we’re not treating the Yellowstone region with sacred reverence. We’re exploiting it, at every turn, trying to wring out every bit of commodifiable worth from a finite mosaic that should be approached as non-expendable.

There’s a perfect word for what ails us—solipsism— and it means being self-centered, self-obsessed, self-indulgent, egotistical, vainglorious and conceited. It is the opposite of altruism, reciprocity, being magnanimous, philanthropic, humble, and modest. What’s ironic about this is that studies show people who spend more time in nature allegedly tend to have values rooted in the latter, not the former, yet the current prevailing pathos in many of Greater Yellowstone’s boomtowns seems to be all about grabbing as much materially for ourselves in this moment as we can.

In terms of examples, try these:

Ask the real estate developer who is building a mass of homes for wealthy vacationers in the middle of an ancient wildlife migration corridor or across pastoral ranchland if he/she has sacred regard for what is being destroyed? Check out this video of a developer who recently bulldozed a rural golf course into a travel route for elk, pronghorn, moose, grizzlies, wolves and other species. At a time in the country when many golf courses are being disassembled and their lands turned back to nature through re-wilding, why are new ones being built in wild settings?

Ask the state wildlife manager who refuses to publicly condemn the practice of citizens chasing down coyotes and wolves with snowmobiles if he/she really believes in human morality, ethics and decency?

Ask the young mountain bikers who are illegally blazing new trails into wild country, by thoughtlessly siting them on game trails long used by resident animals, if he/she/they have respect for those non-humans being displaced or even care about the animals whose homes they are invading?

Is that not a form of heresy, doing short-minded things that violate the wild fabric of a region that is an American treasure?

Were Greater Yellowstone San Vitale in Ravenna we’d be doing the equivalent of chiseling away the precious tiles on the wall and hawking them to the highest bidder. While that approach would leave behind an overt unsightly mess of ruination in Italy, the unraveling that is currently underway here is far more subtle and insidious because of the ecosystem’s capacious size.

° ° ° °

What sets Greater Yellowstone apart more than any other attribute is its wildlife, the soul of wildness itself. This is the only bioregion left in the Lower 48 with all of its original fauna that roamed here in 1491, the year before Europeans reached North America. The hallmark of that is the presence of a complete predator and prey system with terrestrial species still able to migrate across long distances.

Often, we hear a rationalization invoked that we use to justify our voracious behavior. Portraying our consumption as virtuous, we tell ourselves that we are “loving places to death.” How can that be? In fact, this is an impossibility.

No sane human would knowingly destroy a place they love, and they most certainly wouldn’t abide the notion of loving a sacred place to death. We have choices to make, hard ones, and we can’t pretend otherwise because the results of inaction are right in front of us.

We’re all hypocrites,, but let’s not allow our own hypocrisies to become convenient excuses preventing us from striving to do better.

A few years ago, the late Yellowstone Park Superintendent Bob Barbee, whom I had interviewed hundreds of times, was dealing with pressures from funhog recreationists who were relentless in trying to open Yellowstone trails to mountain biking, its rivers and streams to paddlers, and there was the snowmobile industry fighting restrictions on loud, polluting show machines that, in mass, were literally sickening rangers and drowning out the sounds of erupting geyers.

Barbee told me this, “You know, the smooth marble floors in the National Gallery of Art along the National Mall and the nearby National Cathedral in Washington D.C. would, in the assessment of some, provide an extraordinary opportunity for rollerbladers to have fun and they would probably welcome it. They could claim to be savoring the art and the stained glass windows as they flew by it. But allowing them to do that would, of course, be stupid.”

Barbee noted that the most meaningful encounters with the natural wonders of the Yellowstone ecosystem come from strolling at slow speed and soaking in the messages that contain revelations, the biggest being that we are not the center of the universe. One of the paintings in the National Gallery of Art is a depiction of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone by Thomas Moran, a work that helped convince Congress to do something unprecedented with the birth of Yellowstone.

Yellowstone is our mutual, shared national natural cathedral, our living homage to the forces of a creation that does not exist, so far as we know, at any other place in the universe among countless stars, galaxies and planets.

What is it that makes something sacred? Why aren’t we treating a natural wildlife ecosystem, the last of its kind, as sacred? Who is giving it a voice?

On April 3, 2024, Dr. Jane Goodall, who counts herself a defender of Greater Yellowstone and a friend of Yellowstonian, reached 90 years old. She said, “The least I can do is speak out for those who cannot speak for themselves.” As she illustrates, there is no retirement age that lets you off the hook in caring about the future, nor an age requirement for young people to say they won’t let the magnificence of Greater Yellowstone disappear on their watch.

Subscribe

Never miss a story, subscribe to our newsletter!