EDITOR’S NOTE: The following investigative report is long and comprehensive because, to date, a common response from recreationists and the outdoor recreation industry, whenever presented with evidence of impacts from wildlife, is to deny and deflect from the conclusions reached by scientists. We suggest you print this out and fully digest it when you have time. For several months, we have been assembling the data. Pondering the cause and effect of industrial recreation impacts on wildlife holds not only implications for Greater Yellowstone, America’s most iconic large wildlife ecosystem, but it is timely. In recent months and years, a literal grab-bag of bi-partisan bills have been passed by Congress and signed into law by Presidents from both parties. These bills authorize, collectively, billions of dollars in direct and indirect spending to amass/improve/expand grids of infrastructure to accommodate outdoor recreatiton. It will result, over time, in more trails, larger parking lots, more boaters on rivers, and a lot more humans moving through front and backcountry areas of public lands which in many areas are the last viable homes of some wildlife species. One thing overtly lacking: there has been little to no discussion—nor scrutiny voiced by many conservation organizations—about what expanded access and intensified use levels mean for sensitive species which already are dealing with widespread adjacent habitat loss or disruption from development on private lands. In many instances, conservation organizations have stood alongside lobbyists from the outdoor recreation industry touting a mantra that rising levels of outdoor recreation equates to “better and more conservation.” But what kind of conservation is being achieved? The analysis, below, was written by Todd Wilkinson and is adapted/updated/expanded from an essay that appears in the compelling new multi-author book, A Watershed Moment: The American West in the Age of Limits. If you’re pinched for time, scroll down through Todd’s story and read the pull-out quotes from scientists and influential others that will give you the gist.—Gus O’Keefe

by Todd Wilkinson

A few years ago, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Ford gave a lecture at Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana. He spoke of things people say repeatedly that just aren’t true. But, when such assertions are constantly retold and circulated, without being challenged or subjected to rigorous scrutiny, they become part of accepted lore and then are embraced as fact.

Some of these are adages, such as “all growth is good,” or “that wolves are devastating livestock and big game herds,” or that “living the American dream” is equally easy to achieve for everyone. In fact, such assertions are shibboleths and can be mobilized to advance hidden agendas.

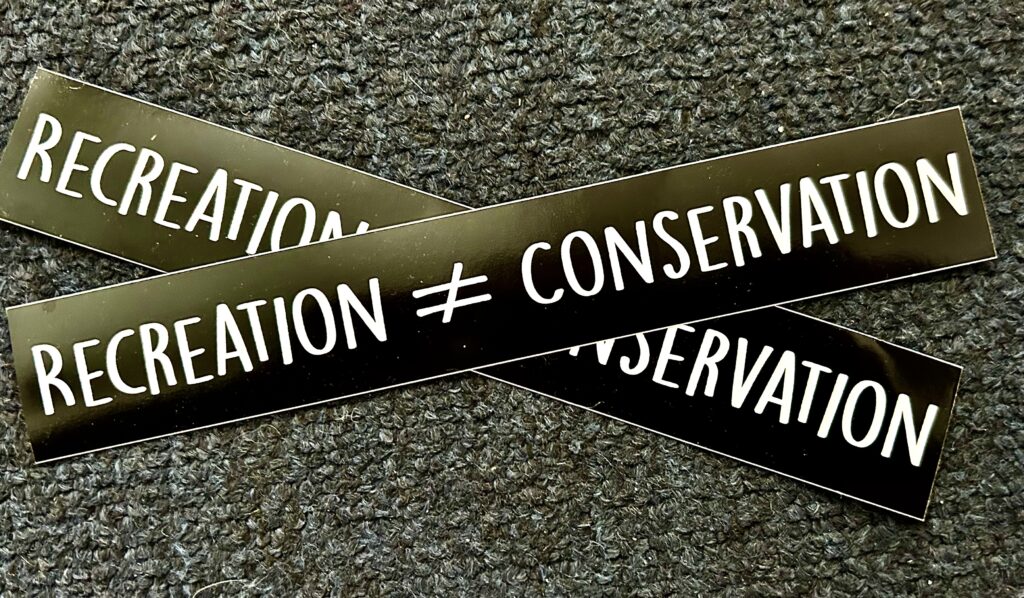

Within the realm of the American West, a more recent assertion that “outdoor recreation is tantamount to wildlife conservation” qualifies as one of those tropes. In truth and through on-the-ground evidence, scientific studies firmly establish that it is often just the opposite—more people, more trails, more infrastructure, and more expanded public access into wild places are not benign. Research upon research upon research confirms that when human visitation goes up in a given habitat, the negative impacts on wildlife rise too.

Despite this evidence, the US Congress and Presidential administrations led by both political parties have worked closely with government agencies like the US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, the powerful outdoor recreation industry and, ironically, some well-known conservation organizations, to dramatically increase the footprint of recreation on public lands. In some cases, they have moved to undermine or weaken longstanding legal protections for the most undisturbed of wildlands that remain. Part of this juggernaut involves allowing public land managers to, at their own discretion and in the name of streamlining approval, invoke categorical exclusions which allow them to evade thorough environmental analysis. Were this allowed to occur with logging, mining, energy and other traditional forms of natural resource extraction, environmentalists would likely be up in arms.

For those who care about the fate of wild nature, they might reasonably wonder: what is the real cost, i.e. the consequences of expanding recreational invasion on the native, indigenous biological diversity of non-human beings living there? Relatedly, maybe, too, it may invite serious reflection on this question now facing us all: does perpetuating the survival of wildlife matter, and if it does, then are we as recreationists willing to change our behavior to ensure it happens? Essentially, are we willing to not be takers?

By now, reading this far, your dander is probably up. To use the lexicon of the times, you might be feeling “triggered,” and you might think: how could I as a pleasure-seeking human with good intentions and a passion for adventure possibly be part of a problem? Before we proceed further, let’s state what is patently obvious: it’s good to be physically fit and outgoing; it’s also good to be conscientious and fully ecologically aware of the wild places we traverse.

“Communing with nature” is what we do to “re-create ourselves,” right? Inspiring self-help books, from noted authors like Richard Louv and Florence Williams tell us what most Westerners who have lived here awhile already know: getting outside benefits us physically, mentally, and spiritually.

I live in a wild corner of the West because I love to recreate outside. If you presented me with a checklist of various outdoor recreation activities I have participated in during my life, I would mark the box that says, “most of the above.” This includes “muscle-powered,” electric, and locomotion propelled forward by the throttling of combustible engines. It includes hunting and fishing. For a long while, I didn’t think much about how my presence might be affecting wildlife, until I began having more conversations with scientists. To raise common-sense questions about the aggregate, unexamined impacts of industrial-strength outdoor recreation is neither anti-recreation, nor anti-fun, nor anti-human; in this case, it is pondered through the lens of being “pro-wildlife.”

Concerns about wildlife and its intrinsic value often are lost within our prevailing, one-way, human-centered orientation toward public lands, and amid public involvement processes designed to decide how such lands will essentially be divied up among different groups of human users and “stakeholders.” In those exercises, seldom is wildlife—or its designated representatives—given a full seat at the table of negotiation.

“Ask yourself this — has the explosive recreational development around Big Sky over the past few decades conserved the area’s forests, wildlife and once-pristine streams? Has industrial recreation around Moab, Utah conserved the surrounding red rock canyons and created more opportunities for solitude? Of course not. While they are often linked, there’s a fundamental difference between recreation and conservation. Recreation is about taking. It’s a form of hedonism. Conservation is about giving. Sometimes that means giving up the opportunity to recreate in certain places or at certain times of the year to protect wildlife. Sadly, far too many recreationists take without giving anything back. That’s why our conservation deficit is worsening in Greater Yellowstone and our wildlife is increasingly under siege.”

—Scott Bosse of the conservation group American Rivers

Studies indicate that people who spend more time in the natural elements, whether in a city green space or remote wilderness, tend to be happier, calmer, more sensitive, caring, and generous. We know, too, that outdoor recreation has generated hundreds of billions of dollars for the national economy and billions each year for states in the Rocky Mountains.

That makes outdoor recreation a bona-fide industry and, like all industries—including the real estate, development and construction industries—year over year “success” is achieved by pushing for an ever-expanding bottom line made possible by generating more clients consuming more stuff; though, in the case of outdoor recreation and those closely related industries above, it is premised on consuming more of finite nature. This makes it extractive.

For outdoor recreation companies, they are constantly pressing for more access to generate more product users so that they can sell more of what they make. And often, they give wildlife only token reference, treating animal presence as nuisances or invisibly as if they don’t exist.

Much has been touted about the muscled swagger of the outdoor recreation industry, but reflection is often lacking on the consequences of large numbers of people venturing into sensitive wild areas and displacing non-human species that often have nowhere else to go. In fact, the outdoor recreation industry and the makers of gear who claim to possess a green consciousness and ecological awareness have steadfastly evaded acknowledgment of impacts on wildlife. At an unspoken gut level, being unable to escape crowds ourselves, we know it can’t be good for wild creatures.

This is a modern phenomenon, wildlife biologists say, that is a growing problem—an elephant in the room— for a region like the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which is world-renowned for the diversity of its wildlife. Yellowstone National Park, its sister preserve Grand Teton National Park, and the other public lands surrounding them represent the cradle of American wildlife conservation, where numerous species have been brought back from the brink of extinction. Never has it contended with the kind of recreation pressure proliferating in places like the Colorado Rockies, Utah, and cities close to the West Coast.

No other bioregion in the Lower 48 possesses the kind of wildness that characterizes the Greater Yellowstone as reflected in its assemblage of wild native species. On a single late summer’s evening you can hear wolves howl, loons trilling, and elk bugling, watch free-ranging bison wallow and bellow, spot a grizzly bear mother with cubs, cast for wild native trout, and soak in a sense of solitude that lets us forget what year it is. Greater Yellowstone is home to all the original, free-ranging wildlife species present 500 years ago prior to the arrival of Europeans.

Here’s the good news offered up front. Overwhelming evidence demonstrates that when humans reduce or control the size of their individual and collective footprints, as well as the intensity and volume of their activity, wildlife can flourish. But this requires us backing off, deliberately making space, understanding cause and effect, and following the pillar of 21st century conservation—the precautionary principle. Are we capable of that?

Here’s the good news offered up front. Overwhelming evidence demonstrates that when humans reduce or control the size of their individual and collective footprints, as well as the intensity and volume of their activity, wildlife can flourish. But this requires us backing off, deliberately making space, understanding cause and effect. Are we capable of that?

Known colloquially as “looking before one leaps,” the precautionary principle requires understanding all variables to avoid unintended consequences that might be destructive and irreversible. Ignoring the precautionary principle already has resulted in huge swaths of the Lower 48 where native species, once present, were eliminated, and never likely will exist in viable populations there again.

All public lands, national parks, forests and wilderness areas in America possess categorical legal designations, but each one is not qualitatively equal in terms of the natural entities an individual location contains. Some parks and wildernesses are less wild than others and bear the impact of human intervention and spread of non-native species; some are more pristine, in that they still can sustain native species; and some are undeniably exceptional, like those in Greater Yellowstone, in that they have the full complement of animals from before European settlement.

Given this, ponder a logical progression: if outdoor recreation supports conservation, then what kind of conservation is it? How does encouraging more people to use/invade limited public and private land benefit wildlife living there? Can we therefore extrapolate this assertion to assume that areas with the most outdoor recreation are thriving meccas for wildlife?

Does Outdoor Recreation Really Result In Support For More Wildlife Conservation?

At the end of the 20th century, Greater Yellowstone and other regions in the Rockies transitioned away from logging, boom-and-bust hardrock mining, and livestock grazing, which were all industries that came at the expense of native species. After World War II, ski resorts became the first form of industrial outdoor recreation. Resort development has been bolstered by the prevailing belief, promoted by the manufacturers of gear, that outdoor recreation economies represent a better, more benevolent alternative to resource extraction. In recent years, some of the mainstream conservation organizations that cut their teeth trying to halt clearcutting of old-growth forests, energy development, and mining on public lands have forged an alliance with the outdoor recreation industry. Together they have advanced three basic arguments treated as gospel.

- Outdoor recreation advances education and financial support for “conservation.”

- Greater access for user groups to public lands translates into more positive “conservation outcomes” and better land protection.

- When recreation happens in landscapes vital to the survival of certain species, it improves public support for “conservation of those species in those places.”

What is the evidence supporting these arguments? Does it exist? Often, some conservation organizations arrayed with the outdoor conservation industry or serving as their silent allies tout vague, sanguine-sounding terms like “balance” and “sustainability” without defining them. You also see the words mentioned routinely in product catalogs for major outdoor brands, likely penned by nature-illiterate copywriters living in cities, encouraging customers to seize their piece of the great outdoors as if it were a blank slate of emptiness just waiting for them to conquer it.

But sustainability, in application, really comes down to asking “what is being sustained, to the benefit of whom, and at the expense of what?”

Does “sustaining” the insatiable appetite of the outdoor recreation industry and its customer minions result in achieving “sustainable” and healthy wildlife ecosystems? Further, what kind of “conservation” is being achieved through outdoor recreation? And, when talking about “balance”—balance between what exactly? Again, how does putting more humans into spaces populated by sensitive species that have only those places as refugia improve their prospects for survival?

Looming large is this curiosity: how often are recreationists, who zealously insist upon claiming more public access for themselves, willing to then give it up if it becomes clear those activities are having deleterious impacts on wildlife? In an iconic wildland bioregion like Greater Yellowstone, if “wildlife conservation” is not the cornerstone of “conservation” that is allegedly being achieved, then what, exactly, is being sustained?

Looming large is this curiosity: how often are recreationists, who zealously insist upon claiming more public access for themselves, willing to then give it up if it becomes clear those activities are having deleterious impacts on wildlife? In an iconic wildland bioregion like Greater Yellowstone, if “wildlife conservation” is not the cornerstone of “conservation” allegedly being achieved, then what, exactly, is being sustained?

Many recreation specialists working for federal and state land management agencies, as well as lobbyists for the outdoor recreation industry and leaders of some conservation organizations, evade those questions or treat them with hostility—even though the agencies that conservation groups exist to hold accountable have a public trust and in many cases legal responsibility to protect and preserve public wildlife.

The premise that “recreation equals conservation” has been spoken often and yet rarely has it been challenged or scrutinized by conservation organizations or, for that matter, by the largely urban media. Recently, for example, developers of a proposed recreation resort, River Bend Glamping Getaway on the banks of the Gallatin River west of Bozeman, utilized the rhetoric. The Gallatin River is a revered Western trout stream that begins in Yellowstone National Park and courses northward. It is one of three rivers that converge near Three Forks, Montana to create the Missouri River. The Gallatin was featured as the backdrop for the 1992 movie poster of Robert Redford’s film adaptation of Norman Maclean’s novella, A River Runs Through It.

In a full-page ad in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle on Feb. 9, 2022, River Bend developers, heeding the advice of PR mavens and mimicking phrases used previously by conservation organizations, declared in bold letters that “Recreation Encourages Conservation.” This ought to leave us interested in learning how saddling a development along a river and increasing river usage could accomplish that goal—in this case conserving the wildlife and essence of a renowned river—if that is indeed conservation?

First, a crucial bit of context: In 2021, Yellowstone National Park notched nearly five million tourist visits for the first time ever— and since the new millennium began, tens of millions of visits in total have been recorded. Grand Teton National Park in Jackson Hole also has seen record numbers crowding natural areas. During the years of the Covid pandemic, parts of the Greater Yellowstone region were inundated with recreation-minded visitors and development like never before. Has this translated into a general appreciation for the conservation of nature? Are recreationists more willing to curb their use of wildlife-rich wildlands?

Relatedly, have we seen a groundswell of citizens rising up to stop sprawl that is simultaneously destroying vital habitat for wildlife on private land and having negative spillover effects on public land? No, we have not. Combined, unmitigated private land sprawl and soaring outdoor recreation are squeezing wildlife at a time when the effects of climate change mean that species will need more habitat to survive—habitat that the outdoor recreation industry sees as a vacant opportunity to exploit.

Yellowstone National Park’s former science chief David Hallac warned a decade ago that the natural fabric of the ecosystem is not just facing death by 1,000 cuts, but death by 10,000 scratches. Small impacts that seem trivial in themselves erode the ability of the land to support wildlife. Outdoor recreation, a substantial number of scientists and studies suggest, brings its own form of lacerating effects.

Yellowstone National Park’s former science chief David Hallac warned a decade ago that the natural fabric of the ecosystem is not just facing death by 1,000 cuts, but death by 10,000 scratches. Small impacts that seem trivial in themselves erode the ability of the land to support wildlife. Outdoor recreation, a substantial number of scientists and studies suggest, brings its own form of lacerating effects.

Interestingly, the glampground mentioned above as well as recreation resorts and luxury guest lodges and zillions of lesser ventures built or proposed to service recreationists by developing real estate, demonstrate how the footprint of outdoor recreation is both an accelerator of private land sprawl while also exacting impacts on public land. Big Sky, Montana may be the emblem of that.

After Gallatin County, Montana commissioners approved the glampground along the Gallatin River, a number of conservation groups sued, some of whom have been avid boosters of increasing outdoor recreation on public land. One of the plaintiffs, American Rivers, and its Northern Rockies Director Scott Bosse, understands the dilemma. Bosse has openly questioned the legitimacy of the recreation-encourages-conservation mantra.

Bosse has earned praise among wildlife advocates around the region who believe that growing levels of industrial-strength outdoor recreation are out of control and for daring to say it. “We used to think of, and tout, recreation as a non-consumptive gateway to conservation, but we seriously need to revisit that,” Bosse told me. “All we need to do is look around at the impacts coming to bear on public and private land. Things have changed quickly and we need to wake up.”

What Bosse says is corroborated by both science and by the fact that in many places where people are, sensitive wildlife species are not. Bosse condemned the Gallatin River glampground in a commentary which appeared in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle. But he also turned heads by broaching a topic that most conservation groups in the region have largely ignored or treated as taboo. “Let’s explore the claim that ‘recreation encourages conservation,’” he wrote. “As a lifelong outdoorsman who lives to fish, hunt, paddle and ski, I’ll be the first to admit that recreating in the outdoors played a huge role in turning me into a conservationist. Many of America’s most celebrated conservationists — people like Teddy Roosevelt, Aldo Leopold and Mardy Murie — got their inspiration to preserve wild country from immersing themselves in the outdoors. So yes, recreation can encourage conservation.”

Bosse then addressed newspaper readers directly: “Ask yourself this — has the explosive recreational development around Big Sky over the past few decades conserved the area’s forests, wildlife and once-pristine streams?” he asked. “Has industrial recreation around Moab, Utah conserved the surrounding red rock canyons and created more opportunities for solitude? Of course not. While they are often linked, there’s a fundamental difference between recreation and conservation. Recreation is about taking. It’s a form of hedonism. Conservation is about giving. Sometimes that means giving up the opportunity to recreate in certain places or at certain times of the year to protect wildlife. Sadly, far too many recreationists take without giving anything back. That’s why our conservation deficit is worsening in Greater Yellowstone and our wildlife is increasingly under siege.”

In September 2024, a study was published in The Journal of Wildlife Management co-authored by two wildlife scientists who have had a high profile working on conservation in Greater Yellowstone—Dr. Joel Berger who helped lay the groundwork for protecting the Path of the Pronghorn wildlife migration corridor and investigating the cause of moose declines; and Kira Cassidy, who has gained renown for her work as a wolf biologist in Yellowstone. The pair have teamed up in recent years to study the effects of recreation on wildlife in southern Utah, especially on sensitive desert bighorn sheep. Their paper is titled Play is a privilege in both humans and animals: how our recreation influences wildlife. Besides chronicling the litany of threats, they write, “Conservation gains for wildlife and biodiversity come about because of nameless advocates who believe that our human footprint needs to be dampened and are bolstered by research on effects of nature-based recreation.”

It’s ironic how American conservationists often accuse the skeptics of human-caused climate change of willfully ignoring evidence that connects burning of carbon fuels with the greenhouse effect and rising temperatures. Can’t it be argued that American conservationists are doing the same thing with the depth of scientific evidence linking outdoor recreation intensity to impairment or destruction of secure habitat for wildlife? Critics of the movement call this a major blind spot that opens it to charges of hypocrisy and having its own inherent bias about the outdoors existing foremost to serve human desires. The bias is that tolerance for wildlife is highest when wildlife does not interfere with human insistence to be in a place.

Shortly after she was hired to be the first director of the Montana Office of Outdoor Recreation, Rachel VandeVoort appeared at a conference on outdoor recreation organized by the Greater Yellowstone Coalition at Montana State University in Bozeman. At the time, Forest Service and Park Service officials, conservation organizations, and a coalition of advocacy groups for outdoor recreation called the Outdoor Alliance claimed there was a huge gap of understanding related to the impacts of outdoor recreation on wildlife. In fact, it’s been staring them in the face all along. They said this as the Forest Service was rallying behind efforts to expand access to public lands in Greater Yellowstone and as the outdoor recreation industry was pushing through bills to dramatically expand infrastructure and allow federal land management agencies to approve it with less environmental scrutiny. Their vague argument was that there was no proof of harm to wildlife. But an unwillingness to look for evidence does not mean evidence is lacking.

“I’ve heard recreationists remark that because they never saw a grizzly bear sow and cubs flee while they were riding their bikes down a trail, it means they’re not having impact on bears or other species,” says Dr. Christopher Servheen, who for 35 years was the federal government’ national grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service. “That kind of thinking is not only ignorant; it’s absurd.” (Servheen also is the father of son, Calvin Servheen, an avid mountain biker who rode trails around Bozeman while at Montana State University and wrote a story about recreationist responsibility for Yellowstonian).

But VandeVoort, at the conference, dismissed worries about impacts: “I have zero, zero, zero, zero, zero, zero tolerance for anybody using the term consumptive vs. non-consumptive. That is a huge bugaboo of mine and it is only creating division because every form of recreation, and recreation itself, is a renewable, sustainable use of our resources.”

Again, the relevant question is “what is being sustained, to the benefit of whom, and at the expense of what?” Servheen says if wildlife is forced to flee or abandon habitat due to intensity of human users of a given space, that is a “consumptive” activity because it removes what an animal needs.

VandeVoort injected another term: “renewable.” What is being renewed, on behalf of whom, and at the expense of what? The outdoor recreation industry loves to invoke a word salad of terms that, in net effect of their implementation, are actually detrimental to wildlife.

“I’ve heard recreationists remark that because they never saw a grizzly bear sow and cubs flee while they were riding their bikes down a trail, it means they’re not having impact on bears or other species. That kind of thinking is not only ignorant; it’s absurd.”

—Dr. Christopher Servheen, who for 35 years was the federal government’ national grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service and is the father of an avid mountain biker

VandeVoort’s assertion does not align with the conclusions of leading scientists who say industrial-strength recreation is neither renewable nor sustainable—nor is it reciprocal nor balanceful when it comes to maintaining wildlife populations having to deal with ever shrinking and fragmented habitat. In fact, plenty of evidence existed before she made her declaration at the Greater Yellowstone Coalition conference (which by the way went largely unchallenged). Just a year after VandeVoort spoke, a major peer reviewed study titled “A Meta-Analysis of Recreation Effects On Vertebrate Species Richness and Abundance” was published in the journal Conservation Science and Practice.

The findings were no surprise to the lead author. Three years earlier Dr. Courtney L. Larson had been part of another landmark study. Larson’s research team completed the largest summary of studies gauging the effects of recreation and human activity on wildlife. Some 93 percent of the studies found at least one significant effect of recreation on wildlife, most of which were negative: “…there is growing recognition that outdoor recreation can have negative impacts on biological communities. Recreation is a leading factor in endangerment of plant and animal species on United State federal lands and is listed as a threat to 189 at-risk bird species globally.”

The authors wrote in the 2016 study: “Effects of recreation on animals include behavioral responses such as increased flight and vigilance; changes in spatial or temporary habitat use; declines in abundance, occupancy, or density; physiological stress; reduced reproductive success; and altered species richness and community composition. Many species respond similarly to human disturbance and predation risk, meaning that disturbance caused by recreation can afford trade-off between risk avoidance and fitness-enhancing activities such as foraging or caring for young.”

In an article of explanation for The Conversation, Larson along with Sarah Reed and Jeremy Dertien who were co-authors in the studies above, wrote that “we examined 330 peer-reviewed articles spanning 38 years to locate thresholds at which recreation activities negatively affected wild animals and birds. The main thresholds we found were related to distances between wildlife and people or trails. But we also found other important factors, including the number of daily park visitors and the decibel levels of people’s conversations.” That was corroborated by a noise study published in 2024 focused on the Bridger-Teton National Forest that found wild animals are more likely to run away from sounds made by hikers and mountain bikers than ATVs.

Corroborating evidence goes on and on, pointing the finger not at one use, but the combined effects of all that cannot be ameliorated by simply focusing on one cause of disruption. For example, in a recent analysis scientists found that”elk were nearly half as likely to occur in locations during summer weeks where the model-based recreation estimate exceeded 22 people/day and the camera-based recreation estimate exceeded 2 people/day. These findings support recent work indicating that low levels of recreation have the potential to displace wildlife species.” Another study concluded “that elk avoided areas where humans were recreating. This avoidance resulted in habitat compression. All-terrain vehicle use was most disruptive to elk, followed by mountain biking, hiking, and horseback riding. When exposed to these activities, elk spent more time moving rather than feeding and resting.”

Creeping sprawl and recreation pressure in Colorado have been cited in elk declines around Vail. The most formidable predator is not wolves but habitat loss. A headline in the Vail Daily newspaper, based on interviews with state wildlife officials, said this: “Colorado wildlife officials say elk herds may not be sustainable over the next 20 years. While elk look plentiful in areas, data tell a different story.”

Another study showed that mule deer may experience increased predation risk when they shifted toward nocturnal activity in response to human recreation. Another study noted that human activity resulted in elk foraging less and showing increased signs of stress. Research has shown that higher levels of human activity reduced habitat suitability for bobcats, gray fox, mule deer and raccoons. Human activity has also been linked to declines in reptile species. Recreation has been cited as a factor in endangerment of plant and animal species on federal lands, and of all U.S. states, California has the greatest number of listed species that are threatened by recreation.

Nonetheless, federal land management agencies continue to greenlight expanded recreation without establishing a baseline of how wildlife behave in largely undisturbed settings, how that changes with differing use levels, how populations have already been impacted, and how much tolerance wildlife has and how populations are affected over time. “Leave No Trace” is a movement that evolved in response to utilitarian attitudes toward recreation. It focuses on seven principles, including keeping a clean camp and packing out trash, with principle number six being “respect wildlife.” But its recommendations, tiered to an urban audience, are soft and superficial at best for how not to displace wildlife.

Often, wildlife disappear or negative impacts ensue even before land managers become aware that they have created a threat by enabling the number of human users to swell. A study on recreation in British Columbia documented impacts. “We found that recreational activity is displacing wildlife and mountain bikers are doing it more than hikers and horseback riders,” Cole Burton, the lead researcher at the University of British Columbia’s Coexistence Lab, told Men’s Journal. “But we don’t know why.”

Burton noted to the reporter that cyclists disturbed wildlife on par with dirt bikes and ATVs. The reporter wrote that “the findings back up other research that suggests self-propelled recreation might not be as good for the wilds as many would like to believe.” And that, according to Burton, the findings align with other studies that show the presence of backcountry skiers and hikers in Canada have a negative impact on mountain caribou, bighorn sheep, and grizzly bears. Just because self-propelled recreation is healthy for humans, the research noted, doesn’t mean it’s benign. Individual episodes of displacement, Servheen says, are not by themselves significant, but over time, they can add up exponentially and users, especially new residents and tourists from out of the region coming to the Northern Rockies to play are oblivious to what’s being lost.

One Forest Service resource specialist with the Jackson Hole-based Bridger-Teton National Forest told me that each year new generations of gung-ho young people arrive and each carries with them boundless desire to seek out more terrain and boast of where they’ve been. They have been taught through marketing messaging from gear companies to seize the day and reject limits. Few are sensitive or conversant in wildlife ecology and within their user cohort groups extreme athleticism is celebrated.

The Forest Service employee, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said recreationists are more demanding and more vocal than wildlife advocates and, over the years, they’ve openly flauted restrictions such as riding in wilderness and wilderness study areas. Rather than hold the line on land protection, the Forest Service acceeds to pressure organized by local user groups and supported by the outdoor recreation industry. Rules put in place to protect wildlife are portrayed as onerous examples of over-reach by the federal government. Recreationists claim they are being picked on or discriminated against. It creates an attitude of smug resistance to wildlife conservation that is also present among recreationists in Teton Valley, Big Sky, and Bozeman.

While federal land managers in the US are often compelled, as a part of the National Environmental Policy Act, carry out an Environmental Impact Statement to assess the consequences of a major proposed timber sale, mine, or oil and gas field, seldom have they, in a broad way, studied or informed the public about the diffuse yet prolific impacts of outdoor recreation. And, tellingly, there have never been calls from conservation organizations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which has one of the highest per capita concentrations of paid wildland environmentalists in the US, to assess the magnitude and cumulative effects of outdoor recreation which affects wildlife on millions of acres of public land. This is, in addition, to activities such as energy development and predator control occurring on public lands to protect livestock.

Often, wildlife disappear or negative impacts ensue even before land managers become aware that they have created a threat by enabling the number of human users to swell. While federal land managers must, as a part of the National Environmental Policy Act, carry out an Environmental Impact Statement to assess the consequences of a major proposed timber sale, mine, or oil and gas field, never have they, in a broad way, informed the public about the diffuse yet prolific impacts of outdoor recreation.

Problems in Greater Yellowstone are compounded by the unprecedented development pressure on private lands adjacent to public land. Sprawl is transforming former farms and ranches, which used to provide vital wildlife habitat, such as winter range and migration corridors, into suburban and exurban landscapes. (Also read these recent Yellowstonian stories: What Happens When Greater Yellowstone’s Conservation Movement Goes MIA On Sprawl? and this one, Subdivisons: As Impactful To Wildlife Over Time As Clearcuts, Mines And Energy Combined).

Dr. Servheen, when he headed U.S. grizzly recovery, had been a proponent of removing grizzlies from federal protection. But together with anti-predator sentiments flaring in the states of Montana, Wyoming and Idaho, and the combination of expanding recreation and development pressures on public and private land, they have caused him to reverse his position and his optimism. As co-chair of the North American Bears Experts Team for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, he has noted that grizzlies are being squeezed out of important habitat, undermining the outlook for bear recovery.

As I type these words stacks of printed scientific studies (in addition to the citations above), news articles, and interview notes with scientists sit before me, and they are complemented by links to many other studies. One notable study that appeared at the onset of Covid and is well worth the read is a special issue of the California Fish and Wildlife Journal, published by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. It is titled “Effects of Non-consumptive Recreation on Wildlife in California.” Together with the analysis of Courtney Larsen and colleagues, this document provides a compelling starting point for pondering the consumptive impacts of recreation everywhere, and it is replete with examples.

Counted among the most aggressive user groups, dismissive of discussing impacts on wildlife, has been mountain bikers and their representative groups, some of whom have tried to undermine the Wilderness Act, or prevent more lands from becoming wilderness lands and they have aggressively pushed to build more trails. Click here to read what scientists had to say about the impacts of mountain biking on wildlife. This is relevant to Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies because mountain biking pressure and conflicts with other users continues to rise.

Nationally, mountain bikers already have thousands of miles of trails and unpaved public land roads to ride. And, by the Forest Service’s admission, many additional miles of trails been built illegally. Bear expert Servheen has found that soaring numbers of mountain bikers threaten bear and human security in the Northern Rockies. Because bicyclists ride fast, quietly, unpredictably, and have their eyes down on the trail, the likelihood of human-bear encounters is higher. In addition, human activity of all kinds causes bears to flee habitat where they otherwise want or need to be. Notably, grizzlies are a kind of bellwether. One peer-reviewed study led by Dr. Charles Schwartz, former head of the prestigious Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, found that a grizzly will exhibit habitat avoidance behavior if a single house and its related infrastructure sprouts on a section of land (640 acres or equal to a square mile).

Another peer-reviewed study in Yellowstone led by Kerry Gunther, Schwartz, Scott Creel and Tyler Coleman found that grizzlies in some of the remotest corners of the park will stay away from backcountry campsites if even a few human hikers are present. Again, the point is not to portray an anti-human attitude; it is to accentuate the fact that every species of wildlife has threshholds of tolerance when humans enter their habitat, beyond which they will abandon those areas for areas that might not be as conducive to their survival.

People also often take their best canid friends into the wilderness with them. When we are recreating with our dogs, especially when off-leash dogs roam widely, the impacts are broadened. Dogs chase and sometimes kill wildlife; they are scourges to ground-nesting birds; they can cause dangerous run-ins with bears, wolves, and mountain lions, and they carry diseases which are shed into the environment through feces and urine. Watch the short video above dogs in national parks but the advisements of Ranger George Heinz in Yellowstone are a reminder of how dogs negatively impact wildlife everywhere.

“I think sometimes people have trouble accepting that recreation has impacts because it’s an activity that ‘we’ [meaning conservation advocates] typically engage in. It was easier when we could point fingers at those building developments or extracting resources, but it’s harder to place blame on ourselves. The impact is also much less visible. Trails do not have a large footprint on the landscape, so it’s easy to think that there are few impacts. Impacts such as wildlife avoidance, stress, and reduced reproductive success are not easily seen by the public.”

—Scientist and researcher Courtney L. Larson who congealed a large body of studies examining recreation impacts on wildlife

Crowded trails became a new norm during the Covid pandemic. This should serve as a wake-up call, scientist Larson told me. “I do think there is more and more attention being paid to this topic of outdoor recreation, especially in the last few years,” she said.

I asked Larson, who is a deep-thinker working for The Nature Conservancy in Lander, Wyoming, why the conservation movement turns a blind eye to conservation? “I think sometimes people have trouble accepting that recreation has impacts because it’s an activity that ‘we’ [meaning conservation advocates] typically engage in. It was easier when we could point fingers at those building developments or extracting resources, but it’s harder to place blame on ourselves. The impact is also much less visible. Trails do not have a large footprint on the landscape, so it’s easy to think that there are few impacts. Impacts such as wildlife avoidance, stress, and reduced reproductive success are not easily seen by the public.”

Such pressures can leave wildlife populations further stressed at a time when resilience is important, especially as climate change alters habitat in myriad ways. In fact, some groups claim, showing little evidence to support their contention, that blanketly promoting outdoor recreation is a compelling strategy for confronting climate change.

As Servheen and other wildlife experts note, resilience means wildlife having access to more habitat – because climate change is going to put more animals on the move. Unfortunately, habitat that is secure from human pressures is in decline. “When we recreate, we are doing activities that are optional,” he said. “It’s a way to spend our leisure time. Our lives do not depend on us having to do things in a certain place or else we’ll die. But that’s what wildlife face by necessity.”

Landscape ecologists say the dispersed nature of outdoor recreation, in every season, means that wildlife seldom get a break. Let’s again state the reality: there is no scientific data which supports the contention that soaring recreation bodes well for wild wildlife. There is little or no evidence to support the contention that more recreation results in better wildlife conservation overall. And there is little evidence that backs the claim that having more recreationists moving into wildlife-rich public lands, especially those being homes to imperiled or sensitive species, results in more financial or policy support for wildlife conservation in those places. Often, recreationists will state their conditional support for putting land under conservation restrictions, but only if they can use them.

The Tetons are a famous line of jagged breathtaking mountains that rise above Jackson Hole to the east, and Teton Valley, Idaho, on the other side of the range, to the west. Their vaulting profile extends southward to a beloved destination for backcountry skiers and snowboarders on Teton Pass. It is crowned by a mecca for powder snow called Glory Bowl. Glory’s mystique among locals has made it a funhog landmark. But during Covid and since, levels of use by backcountry recreationists in some parts of the Tetons has been off the charts.

Wildlife scientists have said that intrepid winter recreationists have disturbed and displaced mountain sheep (bighorns) in their airy haunts. Wyoming Game and Fish wildlife manager Aly Courtemanche has been quoted in the local media saying it is imperative that the human presence, which stresses sheep when they are most vulnerable, be minimized. Among the options being considered by the state of Wyoming, National Park Service, and Forest Service are restricting access or closing portions of the range to protect sheep. At one of the public meetings when these options were discussed, some recreationists voiced resistance. One backcountry skier, incredulous that her personal freedom might be denied or limited in deference to wildlife, responded this way: “Well, the sheep have had these mountains for 10,000 years, now it’s our turn.”

While it obviously cannot be applied to everyone, this kind of attitude, not uncommon, has been a foundation for rationalizing the continued loss of wildlife habitat across the West, as outdoor recreationists, often reciting talking points written by the industry, express an unrelenting desire to claim more terrain. Athletic hedonism, as Bosse references it—or solipsism, the adolescent belief that living with the mindset of Peter Pan and pursuing our self-indulgent personal needs are the only things that matter—is pervasive in mountain towns.

On the Bridger-Teton National Forest, user groups are constantly competing with each other for places to play and some claim it is their right to lay claim to more turf. Lost upon many is that the vast majority of the Lower 48 represents an area where wildlife has been forced to adapt, compromise or vanish in the face of human domination of the landscape. While intense recreation exists in other parts of the Rockies and Utah’s Wasatch mountains, for instance, the likelihood of species being re-wilded there is almost nil. Just as animals have vanished, so has tolerance for their return. A region like Greater Yellowstone is a remnant: it stands as a miracle that it still possesses its biodiversity and yet the outdoor recreation industry treats it as another place to colonize.

Negative impacts are not about a specific use, but a numbers game. They are a function of location, geography, variety of uses, frequency of users and intensity of recreational use. Where there are a lot of people moving through secure habitat for wildlife, animals suffer negative consequences.

Outdoor Recreation Generates Lots Of Money But Does It Sustain Local Biodiversity?

Yes, you can’t fault anyone for wanting to have fun, or make a living, provide for their family, pay their mortgage, and save for retirement—and, for many, outdoor recreation is a source of income. Politicians, gear and clothing manufacturers, outdoor retailers, state tourism offices, outfitters, guides, lobbyists in Congress, and conservation organizations cite how outdoor recreation accounts for over two percent of America’s gross domestic product.

Generating upwards of $1.2 trillion annually in consumer spending, outdoor recreation is the foundation for five million jobs, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Boulder, Colorado-based Outdoor Industry Association. The latter noted that their 2020 figures are probably low because they were calculated in a year of Covid-related restrictions.

Late in 2024, the mother of all outdoor recreation bills, the omnibus “Expanding Public Lands Outdoor Recreation (EXPLORE) Act” was passed. While the industry praised it for unleashing one of the most ambitious expansion of new trails and upgrades, parking lots, boat put ins, and facilities in modern times, many advocates say nature experiences will be monetized like never before and it’s wildlife that will get further steamrolled in the years ahead.

“This is a huge win for the outdoor recreation community and a game-changer for recreation on public lands,” said Hilary Eisen, policy director of the Winter Wildlands Alliance. Get a sense of what different recreational user groups said in a press released written by the Outdoor Alliance. Wildlife was not mentioned once.

For the sake of argument, the petroleum industry generates a lot of revenue and jobs, too, and so does real estate and construction. What puts outdoor recreation in a special category, its promotors say, is that this economic engine is fueled by citizens spending money while engaged in enjoyable leisure activities that also make them healthier, enable them to escape the asphalt jungle, and use public lands that belong to them.

The Outdoor Industry Association, a trade group, asserts a strong link between recreation and conservation—and some of its scripted talking points would likely attract scrutiny from author Richard Ford. “The outdoor recreation economy depends on abundant, safe, and welcoming public lands and waters,” the Outdoor Industry Association states. “The health of individuals, communities, and our economy is tied to opportunities for everyone to experience the benefits of parks, trails, and open spaces.”

It’s true: we recreationists generally do not like getting out into forested clearcuts, strolling through oil and gas fields and boating on streams sullied by mining tailings. Yet, in the face of large numbers of human recreationists descending on public lands and waters, how safe, beneficial and welcoming will they be to wildlife? Not long ago, a large contingent of river protection groups convened in Greater Yellowstone and, along with climate change, they agreed that development pressure and recreational overuse of rivers were top concerns in the West, but they were not shared with the public.

Outdoor recreation has given even conservative states a lucrative steppingstone for pivoting away from resource extraction and the whiplash of boom and bust economic cycles. Recreation tourism fills motel rooms and makes cash registers ring in restaurants, helps outfitters and guides send their kids to college, enables outdoor retail gear shops to thrive, and generates tax dollars. But like all industries, business success is tied to rising profitability, sometimes at all costs, which rests on the zeal to grow user market share—even if “the resource” is diminished. This is connected in turn to unrelenting pushes to put more people into public lands, persuading them to buy pricey gear and recreational vehicles—have you seen TV commercials for sport utility vehicles?— without reflecting on the downsides.

In his 2016 profile of Patagonia clothing company founder Yvon Chouinard for The New Yorker magazine, Nick Paumgarten revealed Chouinard’s disdain for the industrialization of nature as they floated the Bighorn River in Montana. Chouinard said, “When you see the guides on the Bighorn, they’re all out of central casting. Beard, bill cap, buff around the neck, dog in the bow. Oh, my God, it’s so predictable. That’s what magazines like Outside are promoting. Everyone doing this ‘outdoor life style’ thing. It’s the death of the outdoors.”

Chouinard is a part-time Greater Yellowstonian. If he ever needs reminding of the importance of wildlife and giving animals a voice, he gets it, everyday, from his advocate wife, Malinda, who routinely expresses her concern about grizzly bears, wolves and bison. Never far away either is Kris Tompkins, wife of Chouinard’s late best friend, the adventurer Doug Tompkins. Kris served for years as chief executive of Patagonia and then, with Doug, they embarked upon an ambitious and ultimately successful effort to buy land in Chile and set it aside as national parks and protected areas. Kris, too, sees the trendiness of industrial recreation and has said to me what she’s repeated elsewhere, that “landscape without wildlands is just scenery” and that wildlands are never truly wild without the native creatures that call them home.

“When you see the guides on the Bighorn [River], they’re all out of central casting. Beard, bill cap, buff around the neck, dog in the bow. Oh, my God, it’s so predictable. That’s what magazines like Outside are promoting. Everyone doing this ‘outdoor life style’ thing. It’s the death of the outdoors.”

—Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, conservationist, eco-warrior, mountaineer, fly-fisher and reluctant funhog idol in The Yorker magazine

But who in the conservation world has the guts to call out the new swaggering industry whispering in our ears, assuaging our egos and telling us that playing is an expression of courageous activism? I have read tens of thousands of words, at least, posted and circulated by entities like the Outdoor Alliance, Winter Wildlands Alliance and others which purport to be promotors of conservation but which have aggressively pushed for more access. Wildlife is rarely mentioned on their websites or the op-eds they submit to media outlets, and if it is, wildlife is only cited generically without acknowledging the negative impacts of recreation on non-human species. It obviously is part of a script of strategic messaging.

This is the same kind of mindset that environmental groups have historically harshly criticized extractive industries for having. In fact, it could be argued that trees will grow back in a Pacific Northwest clearcut, but recreation pressure, represented by numbers of people and infrastructure, can cause permanent damage because once user groups gain access they will fight to keep it. Arguably, outdoor recreation, where the well-being of remnant wild wildlands is concerned, is one of the last frontiers of acknowledging the need for limits.

Nobly and ironically, the Winter Wildlands Alliance in 2021 produced one of the few reports in circulation from an outdoor industry group that identified the environmental impacts from recreation on wildlife. The report concludes: “The existing body of evidence indicates that winter recreation can have a substantial impact on wildlife and natural resources if not properly managed. Given our growing understanding of the catastrophic declines in biodiversity, along with fast-increasing pressures of habitat fragmentation from climate change, increased and expanding recreation use and development, we must incorporate this science into sound recreation management that errs on the side of conservation and protection of species and natural resources.”

“The existing body of evidence indicates that winter recreation can have a substantial impact on wildlife and natural resources if not properly managed. Given our growing understanding of the catastrophic declines in biodiveristy, along with fast-increasing pressures of habitat fragmentation from climate change, increased and expanding recreation use and development, we must incorporate this science into sound recreation management that errs on the side of conservation and protection of species and natural resources.”

—Report from Winter Wildlands Alliance

But telling is that publicly, at least, the organization did not highlight wildlife concerns in a slough of recent bills passed in Congress, like the EXPLORE Act and signed into law that will result in billions of dollars’ worth of new recreation infrastructure bringing more people into sensitive wildlands, resulting in more certain displacement of wildlife.

Scientists are concerned that the expanding and unchecked outdoor recreation complex (which involves not just using public lands but the development superstructure that supports it on public and private lands) will be a major contributing factor to the undoing of Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife. It’s why some call it the “wreckreation industry.”

The Gallatin Mountain range is a prime example. Consider this: the Gallatins today are wilder, based on the diversity of species present there now, than Yellowstone was in 1872. The only reason they are that way is because they’ve been protected from intense levels of traditional resource extraction and from large numbers of people using them.

Arguably, the Gallatins are as important to Greater Yellowstone and the adjacent health of Yellowstone Park as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is to perpetuating the legacy of wildlife in Alaska. They provide habitat for grizzlies, wolves, elk herds, bighorn sheep, moose, and bison wandering out of Yellowstone and, at times, rare wolverines and Canada lynx. In fact, based on the composition of species, the Gallatins would be the wildest line of mountains in nine of the 12 Western states, absent the mountains in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho. If, based on their mammalian diversity, they were a national park, the Gallatins would be wilder than any national park outside of Yellowstone, Grand Teton and Glacier. Notably, they would be wilder than any federally designated wilderness area in those nine other states, too.

Arguably, the Gallatin Mountains are as important to Greater Yellowstone as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is to perpetuating wildlife in Alaska. They provide habitat for grizzlies, wolves, elk herds, bighorn sheep, moose, and bison wandering out of Yellowstone and, at times, rare wolverines and Canada lynx. In fact, based on the composition of species, the Gallatins would be the wildest line of mountains in nine of the 12 Western states, absent the mountains in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho

Acknowledging the Gallatin Range’s stature in the upper one percent of true wildlands left in the Lower 48 offers a focal point for thinking about the divide between wildlife conservation advocates and outdoor recreation. Debate over the applied meaning of real conservation is important. Read the pull-out quote from the Winter Wildlands Alliance report on threats facing wildlife again. It’s as if little of it was considered by the Forest Service in the Custer Gallatin National Forest’s new forest plan, nor with the Gallatin Forest Partnership’s proposal that limits the amount of wilderness lands being protected in the Gallatin Range out of deference to mountain bikers, snowmobilers and other recreationists. Sparse on science as it relates to impacts on wildlife, the Gallatin Forest Partnership—comprised of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, The Wilderness Society, Wild Montana, the Winter Wildlands Alliance, mountain bike groups, backcountry horsemen and praise from the Outdoor Alliance—has a drafted a bill for submittal to Congress (involving the fate of the Gallatins)— that has been roundly criticized by a long list of veteran conservationists and scientists.

While Wild Montana rebranded itself—it was formerly known as the Montana Wilderness Association and dropped “wilderness” from its name because it claims the word is racist—automaker Subaru thinks the word holds mass appeal, inspiring its Forester Wilderness vehicle line. Ironically, this car commercial, like many produced by SUV makers, does not exactly promote respect for the American outback nor sensitivity for wild denizens living there.

Critics of the Gallatin Forest Partnership include Mike Finley, renowned for being a former superintendent of Yellowstone, Yosemite and Everglades national parks. Finley was a longtime board member of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, he recently served as chairman of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, and, when he served as president of the Turner Foundation, he was instrumental in creating the Outdoor Alliance. He helped get the Outdoor Alliance off the ground because he thought “it would be a strong advocate for real wildlife conservation” but said recently “it has drifted far off course from that.”

Questions about the commitment of conservation organizations to wildlife protection, versus advocating more strongly for rising levels of recreation, fester in communities throughout the Rockies and public-land-rich West.

To return to Richard Ford’s proposition, tropes and memes keep getting used and embraced by the public as fact when they aren’t. The late conservation biologist Michael Soulé told me that much conservation thinking today seems stuck in an old paradox. Protection of wildlands, the premise goes, can’t be politically justified unless wildlands are being used (up) or monetized by people. But wildlands are being used, he said. They’re richly inhabited wellsprings for biodiversity at a time when we are dealing with an extinction crisis. They are priceless systems that humans cannot engineer or be replicated if the pieces have been stripped down or liquidated.

The Only Way to Truly Safeguard Wildlife Is Limiting Human Consumption of Nature

I crave to be outdoors moving my body, getting the heart pumping, activating the senses, unplugging from gadgets and trying to be empathetic to the fact I am entering someone else’s home. No one goes wildlife watching in a gymnasium, yet we treat wildlands as if they were health clubs, there for us to work up sweats, and we are oblivious to knowing the difference.

Recent annual reports from economists working for the National Park Service have estimated that the economic value of nature-tourism generated by Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks approaches $1.5 billion annually and is linked to 15,000 jobs. Next to seeing Old Faithful Geyser erupt, the top two draws to Yellowstone are grizzly bear and wolf watching. One study found that visitors would be willing to pay twice as much for an entrance fee if they were guaranteed a better chance of seeing a grizzly.

A recent study by the University of Montana and touted by an entity called Wild Livelihoods (comprised of companies in Park County, Montana that benefit from nature tourism) pegged the annual value of wolf watching in Yellowstone at $83 million. Were the economic activity ever tallied relating to the appeal of famous Jackson Hole Grizzly 399 and her cubs—and all griz watching opportunities in Grand Teton Park—no doubt it would be measured in the tens of millions of dollars annually. Yes, grizzlies are worth exponentially more alive to the Wyoming economy than dead.

Consumption of wildlife and debate about sentient animals being “a renewable resource” like corn or timber can take many forms. As renowned Jackson Hole wildlife photographer Thomas D. Mangelsen says: The late Grizzly 399 and the opportunity to see her year after year provided enjoyment to millions of people and inspired them to care more about wildlife. “If a sport hunt of grizzlies is ever brought back, the person who gets a hunting tag will kill the bear for fun and privatize the value of that bear all for himself as he aims to turn it into a rug or stuffed animal for bragging rights.”

But bears can disappear from habitat without being shot. In Forest Service lands, especially with mountain bikers, there is an ongoing problem of “user-created trails” that the agency, to date, has refused to uniformly confront. Outlaw bikers who blaze new trails are treated inside their own community as heroes. Not only do some managers deny there are impacts or claim there is a paucity of evidence, but they also admit that if there are impacts they do not possess the staffing resources to measure them or to halt the rampant creation of new trails. Young mountain bikers have told me the trails they create are advancing conservation and when I ask them to elaborate they seem confused by the question. As scientists have told me, many user-created trails begin by riders who co-opt game trails (first charted by wildlife away from human trails), and when humans claim them as their own, this results in wildlife being further displaced.

Here’s what biological and social scientists found in the study, mentioned earlier, by the California Department of Fish and Game. “Collectively, the results show that managing tourism in protected areas in a manner that reduces such impacts is essential to providing beneficial cultural ecosystem services related to human health and wellbeing.” They add that “To capitalize fully on the positive aspects of tourism (including recreation) for protected areas, the degradation of resources needs to be constrained to ecologically acceptable levels.” Wildlife presence and healthy is a barometer of that, and it means having wild animals, not only species capable of becoming habituated.

The Forest Service is a bureaucracy driven by a “multiple use” mission to accommodate as many kinds of human uses as possible—especially when politicians dangle enormous amounts of money to carry it out. If an area becomes crowded, a local forest supervisor may recommend building a larger parking lot, or say that in order to alleviate congestion, more recreation will be “dispersed” into other “underutilized” areas of the front- or backcountry. What often results are crowded areas remain crowded and traffic directed to other areas results in more impacts there; as if the prime objective is to fill up as much of a public land with human presence as possible. Employees gain promotions if they favor recreation over perpetuation of non-human species.

Plus, in addition to all this, outdoor magazines, travel writers, state tourism offices spending millions on advertising, and some conservation organizations call attention, in print and social media campaigns, to “the most undiscovered secret trails” in a given park, forest or BLM land which inevitably means they will not remain that way for long. If we were able to ask them, few wildlife species would ever call the habitat they need “underutilized.” Does wild nature need more human publicists or more watchdogs? This video by Jackson Hole Stay Wild raises many questions, including how local tourism promotors define sustainability for what and whom.

Protecting biodiversity means being able to empathize with other beings. To contemplate what an animal needs requires modesty and humility. At the beginning of this essay, I noted how research shows humans who spend more time in nature are happier, calmer, more sensitive, caring, and generous. Does that translate into us being more magnanimous in the way we think about wildlife?

What good is human prosperity if it comes at terrible cost to wildlife, diminishes the environment, and displaces working class citizens who make huge contributions to socially holding communities together?

We need a strategy for safeguarding Greater Yellowstone and other mountain ecosystems. We need a national “backpack tax”—assessed on all outdoor gear and equipment sold with the proceeds going back into wildlife habitat protection to offset the amount of terrain already lost. No consumer would balk at paying it. Hunters and anglers already pay their version of a tax. The outdoor retail industry, concerned about answering to shareholders or wanting to pad their own profits, rallied to oppose a backpack tax a quarter century ago. Poll after poll, study after study, as well as other reports, show that Greater Yellowstonians and Westerners value wildlife—that its critical to how we relate to, and identify with, the landscape.

We need a new conservation ethos if we want to hold onto the miracle of wildlife in a region like Greater Yellowstone. And it ought to have as its bedrock wildlife conservation.

Famed American ecologist Aldo Leopold, in the 1940s, anticipated the flight of masses of people from urban areas to a region like Greater Yellowstone. “The greater the exodus, the smaller per-capita ration of peace, solitude, wildlife, and scenery, and the longer the migration to reach them,” he observed. In the last page of his classic A Sand County Almanac, Leopold warned of ego-indulging recreationists. “The trophy-recreationist has peculiarities that contribute in subtle ways to his own undoing. To enjoy he must possess, invade, appropriate. Hence the wilderness that he cannot personally see has no value to him. Hence the universal assumption that an unused hinterland is rendering no service to society. To those devoid of imagination, a blank place on the map is a useless waste; to others the most valuable part. Is my share in Alaska worthless to me because I shall never go there?”

“The trophy-recreationist has peculiarities that contribute in subtle ways to his own undoing. To enjoy he must possess, invade, appropriate. Hence the wilderness that he cannot personally see has no value to him. Hence the universal assumption that an unused hinterland is rendering no service to society. To those devoid of imagination, a blank place on the map is a useless waste.”

—Aldo Leopold in A Sand County Almanac

Curt Meine, the award-winning writer who wrote a biography of Leopold, shared this observation with me: “Leopold understood and appreciated recreation as one of the primary ways in which modern Americans interacted with land and the natural world—and through which we could develop a personal land ethic. And so he devoted substantial time throughout his career to providing recreational opportunity through wildlife conservation, wilderness protection, land restoration, and other means. But he also understood that recreation could also become just one more modern expression of consumption—of taking from the land without regard to its beauty, diversity, or health.”

How often do federal land management agencies or conservation organizations leading consensus and collaboration efforts ever begin by first asking: what are the absolute biological and spacial needs of wildlife, considering all of the converging forces already underway, and then projecting what habitat will look like in another human generation given current trendlines? Almost never. In fact, it’s usually just the opposite. Conservationists start with focussing on maximizing recreational opportunity to appease differing user groups with the tacit expectation that wildlife, which already has given up much, will somehow adapt. Likely, however, many species won’t.

In his groundbreaking and most excellent book, Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv, a friend, made a compelling case in asserting that the antidote to nature-deficit disorder in young people is exposing them to nature. He and I have spoken about this. The overwhelming majority of young people in America today live in cities and suburbs and bringing them to green spaces and local nature preserves can be positively life changing. But arguing that treating the wildest of wildland crown jewels that remain as human gyms to serve large numbers of us—in places which are home to the most sensitive of species in desperate need of secure habitat—warrants scrutiny.

Eventually, there could come a time in Greater Yellowstone when we recreationists set out looking for wildlife species with the younger generations and discover the animals are no longer there. What kind of lesson in conservation is that?

One possible conclusion: it would be a strange kind of conservation where the persistence of wildlife, by our choice, wasn’t made a priority, and the justification involved using a deflective vocabulary of nice-sounding, virtue-signaling words that actually meant little or nothing for the creatures being affected by them most. Edifyingly, this just might be the very quintessence of us thoughtlessly—and willingly— loving our most precious wild places to death, all in the name of us having fun.

° ° ° °

Reader comment:

Nice piece on wreckreation. Two reasons it is all about growth: 1. Every state tourism office, research center, and marketing board gets it’s funding from the tourist industry in the form or room tax, sales, etc. The more they bring in the more they can grow their budgets and staff. 2. 90% of tourism research is about marketing and very little is about impacts. I published impact of tourism articles for two decades. They were always hard to get into journals that were supported by the industry. Oddly, they are still the most cited articles I wrote and most of those come from developing countries trying avoid the negative impacts of tourists and tourism.

The grizzly bear is a monitor for our impacts. As we grow backcountry use the bear will show us that we have gone too far and it will probably affect water, fish, fire, conflict, and congestion.

—Jerry Johnson, Bozeman, Montana

Jerry Johnson was, for decades, a professor of political science at Montana State University in Bozeman with a special interest in assessing how and why outdoor recreationsts interact with backcountry terrain. Johnson also collaborated with colleagues in the Department of Ecology, Drs Andy Hansen and Bruce Maxwell, on analyses looking at the causes and effects of sprawl on natural lands, and the forward-looking consequences. Here is a link to one multi-author paper that appeared in the journal BioScience in 2002: It is titled “Ecological Causes and Consequences of Demographic Change in the New West: As natural amenities attract people and commerce to the rural west, the resulting land-use changes threaten biodiversity, even in protected areas, and challenge efforts to sustain local communities and ecosystems”