A Note From Yellowstonian co-founder Gus O’Keefe

In an extraordinary video presentation below, journalist and Yellowstonian founder Todd Wilkinson has a conversation with Gregory Nickerson of the Wildlife Migration Initiative and Dr. Jeff Reed, a Montana conservationist, about the larger ecosystem and what’s happening to animals near Yellowstone Park.

We think you will be amazed listening to Nickerson and Reed hold forth with perspective and images. In this, the third decade of the 21st century, many consider it a miracle that Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife migrations still exist.

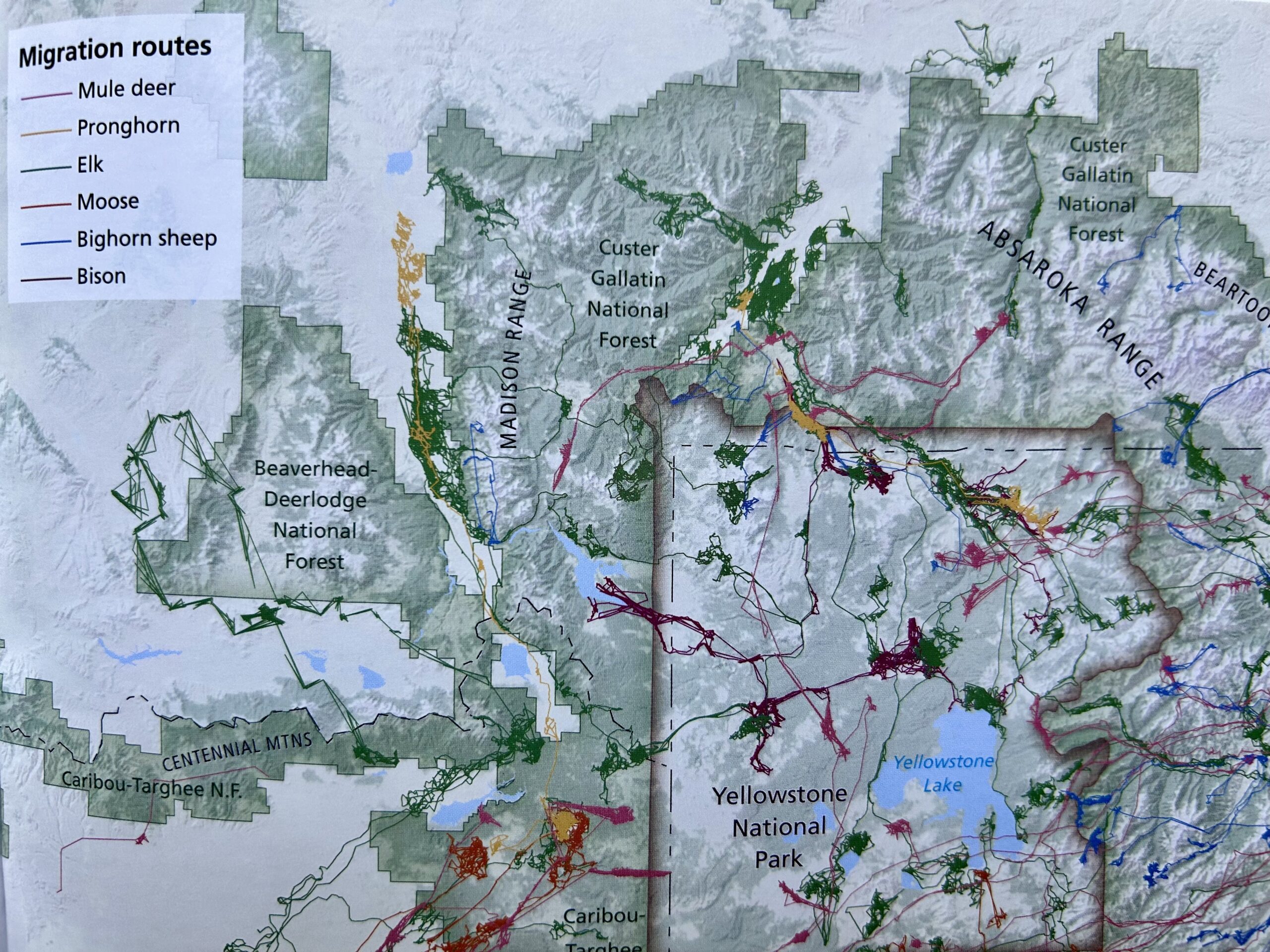

The conversations happened as part of the 2024 Yellowstone Summit organized by Jenny Golding and George Bumann. They enlisted Wilkinson and Yellowstonian to moderate the discussion. Nickerson’s employer, the Wyoming Migration Initiative, is at the forefront of mapping wildlife migration corridors in Greater Yellowstone and leading a global discussion on how to save those that remain from ruination. Nickerson is currently writing a book about migrating mule deer. Greater Yellowstone has the longest-documented migrations of pronghorn, elk and mule deer. The truth is that most large mammal species either migrate or move seasonally—if they can and their pathways are not blocked by development.

Reed by profession is a high-tech wizard involved in the study of bioacoustics among many personal and professional projects. He also is involved with the Upper Yellowstone Watershed Group and Wild Livelihoods Business Coalition that highlights the economic value of wildlife-related nature tourism in the northern part of Greater Yellowstone.

As my journalist colleague Todd Wilkinson writes, “Migrations are like Greater Yellowstone’s biological electrical, circulatory and pulmonary system all rolled into one. In a profound way they move around caloric energy which feeds the entire wild food chain. Energy from the sun, combined with clean water and soil, is converted into calories in plants; native plants are eaten and enhanced by the herbivory by wild ungulates; those ungulates are eaten by predators and dozens of different scavengers, from raptors down to microbes. When animals die their remains inject nutrients back into the system. Because ungulates move long distances in both space and at certain times of the year, their biomass is distributed over large areas. Their ability to move hinges on whether the ancient corridors they frequent are not blocked by human development.”

Migrations are like Greater Yellowstone’s biological electrical, circulatory and pulmonary system all rolled into one. Dr. Matthew Kauffman, who leads the Wyoming Migration Initiative with the USGS. says the single biggest threat to the persistence of migrations in Greater Yellowstone is the proliferation of rural residential subdivisions and sprawl on private land.

Wilkinson, who has written for years about Greater Yellowstone’s migrations, including for National Geographic, adds, “Animals that can’t migrate how fewer survival options and they end up becoming isolated as ‘island’ subpopulations. Island populations of species disappear at a much faster rate than those which have healthy migration options. The wildlife migrations are considered a wonder of the world, like those found in the Serengeti of East Africa and the high steppe of Mongolia.”

Dr. Matthew Kauffman, who leads the Wyoming Migration Initiative with the USGS, says the single biggest threat to the persistence of migrations in Greater Yellowstone is the proliferation of rural residential subdivisions and sprawl on private land. While the ecosystem has big sweeps of public land, it’s private land that plays a crucial role in enabling wildlife to migration. Dr. Arthur Middleton, a conservation biologist who has his own lab at the University of California-Berkeley, works closely with Kauffman, and who spends his summers in Cody, Wyoming, has used these analogies:

The movements of nearly a dozen different elk herds, which converge upon Yellowstone every summer from distant corners of the ecosystem, are akin to a pulmonary system, in which the national park breathes elk in during the warm months as they drawn toward the high country by greenup; then elk are “exhaled” when they head to lower ground in winter across more than 100 miles in some cases. The journey between lower and higher ground depends on having open corridors on private lands. Not altogether different from people who live in Teton Valley, Idaho but who work in Jackson Hole needing a reliable and open Teton Pass.

Kauffman has also noted that when wildlife corridors become blocked it is like a human suffering a blood clot in a major artery which can cause stroke or death to the body. In the two-part conversation we are sharing with you here, Nickerson discusses the remarkable macro picture of wildlife migrations in Greater Yellowstone while Reed examines what is happening in Park County, Montana.

Make sure you pay attention to what Nickerson says about the importance of applying indigenous knowledge to the cause of protecting wildlife corridors and how it is complementing/enhancing the insights being realized through science. After you listen to our conversation, also read Nickerson’s tribute to long-distance traveler Mule Deer 255 who passed away this spring at age 10 years, 10 months old.

(Note: Images above are from Atlas of Yellowstone, 2nd Edition, a book we strongly recommend adding to your bookshelf).

Finally, a friendly note to our growing fanbase: Yellowstonian is a site devoted to delivering great conservation journalism, elevating public awareness and building a more enlightened nature-loving community. We exist to give you the best available information about how to safeguard wildlife and wildness in Greater Yellowstone and beyond. If you enjoy forums like this, please support us. We’d like to host more of them. Most of all, we value having you as a member of this community.

Support Yellowstonian and

Get Some Real Cool Visual Stuff

From now through the end of July, Livingston-based Artemis Institute, the parent non profit entity of Yellowstonian, is participating in the Park County, Montana Community Foundation’s Give a Hoot fundraiser and all contributions made to Artemis Institute will support Yellowstonian‘s mission of providing conservation journalism focused on Greater Yellowstone. We would be profoundly grateful for your support and here’s your chance to get a really cool visual reward for your generosity: Anyone who contributes $35 or more will receive their pick of one individual species poster below or all three for $100. For a donation of $350 or more, supporters will receive a special, limited-edition collector’s lithograph that features all three of Greater Yellowstone’ species’s icons. It is hand-signed by Eric Junker.