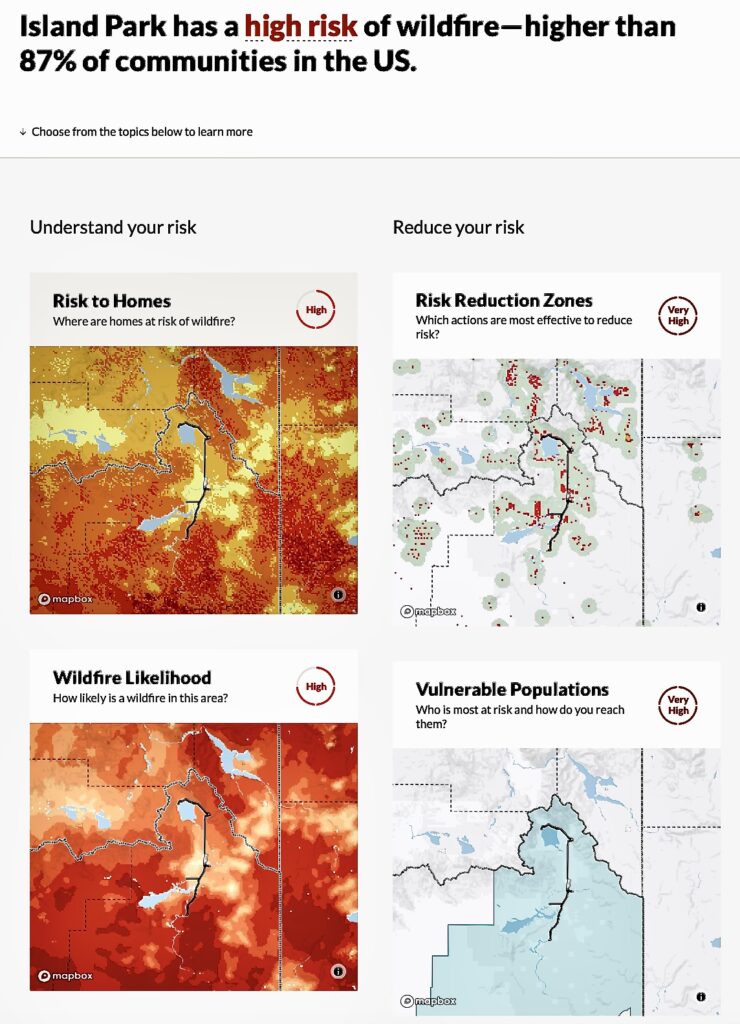

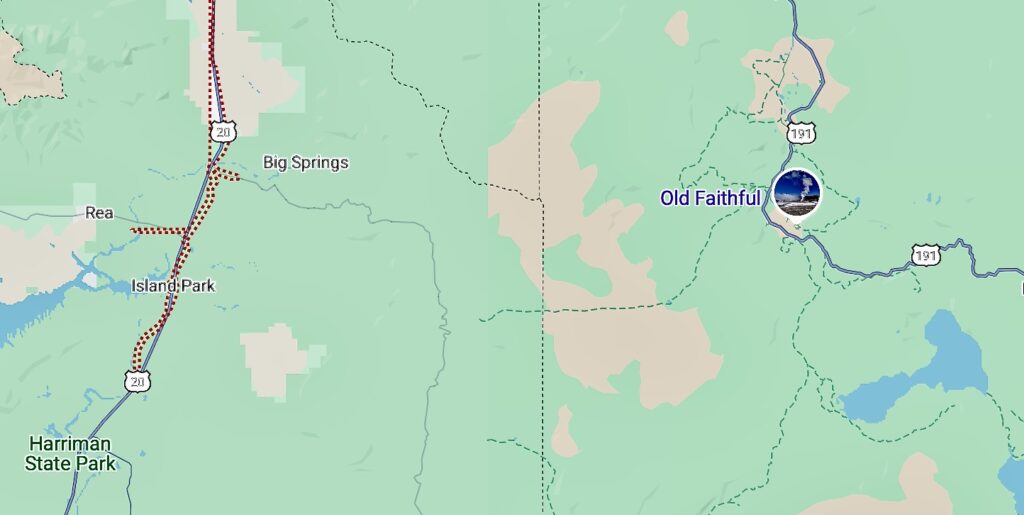

EDITOR’S NOTE: A book of essays, A Watershed Moment: The American West in the Age of Limits, is in fresh circulation and already it’s spawning discussions up and down the Rockies. Several of the pieces focus directly on issues in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem or topics relevant to our region. Yellowstonian is proud to bring you a number of excerpts which demonstrate the thoughtfulness that went into assembling this volume by its three editors, Robert Frodeman, Evelyn Brister and Luther Propst. In the excerpted essay by Paul C. Rogers that follows, he visits Island Park, Idaho on the western side of Greater Yellowstone (just west of Yellowstone National Park) which has been described as one of the largest small towns in the West. Rogers has had a distinguished career pondering our human relationship with nature. Read his bio. Island Park is a place where thousands of vacation homes sprawl throughout a vast forested landscape vulnerable to wildlife (and it is also located inside some of Greater Yellowstone’s vital wildlife migration corridors). Over the years, residents of Island Park have expressed libertarian sentiments and open defiance against any kind of government regulation emanating from the federal, state and local levels. And, as Rogers notes, the community has backed itself into a corner with its resistance to preparing itself for inevitable fires, with more people each year building dwellings inside the wildland-urban interface. It begs the question: sprawl located inside the forest exacts a huge ecological cost on wildlife living there; how much more harm will occur fire-proofing structures and stripping back more of the forest, to prevent property damage and worse, potential loss of life? Rogers’ piece will force you to think, it speaks to the quality of the essays in A Watershed Moment (which we recommend adding to your bookshelf) and it holds lessons for hundreds of other towns dealing with peril as they sprawl into the forested West. (By clicking on this link, you can go to the USDA/Forest Service’s Wildfire Risk to Communities page and type in the name of your town to see how it is rated for risk of wildlife. —Todd Wilkinson

“Across the American West, some communities are inherently more flammable as a result of their proximity to standing forests. Such locations, when lacking resources and prone to individualistic ideologies, are particularly vulnerable to conflagrations. Island Park, Idaho is one such community.”

by Paul C. Rogers

Fire screams for our attention. A forest ablaze is nature’s sensational headline. The images draw a visceral reaction: do something! The response for the past century has been to suppress wildfires. Our policy was to send teams of firefighters to douse ignitions before 10 am the next day. In hindsight, suppression itself is at fault, bringing an unprecedented menace in the form of accumulated fuels into today’s forests. Yet we go on battling these flames with boundless budgets and military bravado.

How should we respond to future fires?

Across the American West, some communities are inherently more flammable as a result of their proximity to standing forests. Such locations, when lacking resources and prone to individualistic ideologies, are particularly vulnerable to conflagrations. Island Park, Idaho is one such community. A retreat for the middle class, Island Park is deeply rooted in conservative politics, combustible fuels, and ample sources of ignition.

The Island Park caldera, like its better-known and younger Yellowstone neighbor, was born in cataclysm. The rhyolite soils from prior eruptions some two million years ago provide a foundation for broad expanses of fire-prone lodgepole pine. Sitting at 6300 feet, residents of Island Park rest on this dormant volcano, its getaway homes spreading across landscapes also frequented by campers, fishers, and urban refugees.

Unlike many of the West’s iconic resort destinations, most of the dwellings in Island Park are modest. Clearly not a Santa Fe, Vail, Park City, or even nearby Jackson, Island Park’s unpretentious existence still faces significant hurdles given its ripe setting for wildfire.

Chief among the challenges of Island Park, and what sets it apart from the storied playgrounds of the West, are its humble trappings: wood cabins mingle with aluminum trailer homes alongside a scattering of small subdivisions. It’s a middle-class model of escapism dropped into a forested Rocky Mountain setting.

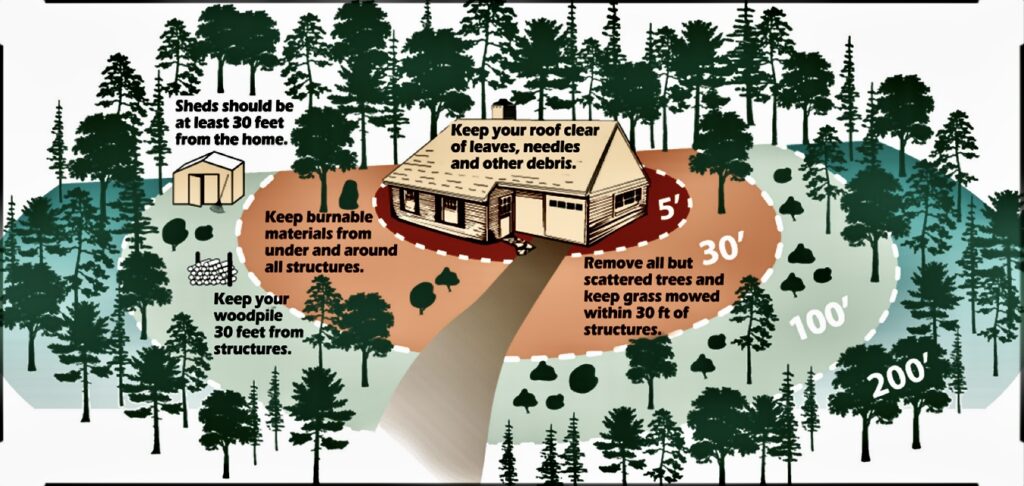

Dwellings in the 800 to 3,000 square foot range are markedly different from the likes of a Sun Valley mansion, a Park City second home, or a Telluride estate weighing in at several thousand square feet. Obviously, size isn’t everything, but it does provide a measure of ready resources. To create a “Firewise” landscape in Vail requires writing a check to professional arborists or landscapers. (Firewise is a series of actions taken to clear fire-prone fuels and other materials away from homes).

In Island Park, most homeowners will be investing in personal equipment and callused hands for several years to clear underbrush and overhanging trees themselves. More realistically, many seasonal visitors and permanent residents will do nothing and hope for the best. This strategy of inertia usually results in dire outcomes, at least from the perspective of the homeowner.

A second challenge is the dominance of individualism found in much of the Interior West. Although many of the iconic Western resort towns are populated with extra-regional “outsiders” bringing decidedly non-individualist philosophies. In many ways Idaho epitomizes the libertarian bent that limits civic action and champions personal intention.

In the past, however, our greatest trials have required collective action. Lessons learned from the Civil War, the World Wars, the Great Depression, and myriad natural disasters have shone a bright light on Westerners coming together, sacrificing comforts, lending a hand, and compromising for the greater good. We can draw on that experience to shape our approach to managing wildfire, even in communities that prize individual liberty.

How Did We Get Here?

North America didn’t have a wildfire problem prior to Euro-American settlement (nor water use crises!), although periodic climate fluctuations certainly presented challenges to Native people. Living within the limits of Western ecosystems means living with flames. Thomas Vale’s 2002 book Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape, showed that multiple regions across the West had similar patterns of aboriginal burning.

Native peoples settled in much the same areas as immigrants, showing a preference for valley bottoms with water, fertile soils, and relative ease of travel for food acquisition. While acknowledging wide variability in Native customs and forest types, a common pattern emerges of localized fires near established villages and seasonal camps, with less human-caused fire in less-traveled mountainous terrain. No doubt, as with today’s prescribed burns, Native-set blazes must have occasionally escaped intended areas when conditions in adjoining terrain and vegetation were susceptible.

Today one commonly hears the phrase “100 years of fire suppression” to underpin the notion of overly dense forests that are fueling wildfires often described as unprecedented. Viewed in isolation, this theory seems plausible, but the ultimate drivers of wildfire are more likely vegetation type and short- and long- term weather patterns. Suppressing fires, sometimes successfully, has led to more severe events in some locations and little effect elsewhere.

Late in the 20th century federal agencies pivoted to more holistic approaches in land management, including allowing some fires to burn. As federal agencies transitioned from managing land for optimum timber production to whole ecosystem management with multiple goals, fire management also changed. At the same time, the transition to ecosystem management has not been smooth—in fact, most western state governments remain steadfastly tied to short-term, single-resource harvesting. Contrasting federal-state mandates, intermingled with private property prerogatives, undermines coordinated fire approaches. Moreover, understanding fire in the arid West requires making systematic connections to maintain ecosystem processes rather than being exclusively focused on traditional commodity, or single-species, stewardship. A tenet of modern fire management is making critical process-based linkages to climate.

According to the multi-century Palmer Drought Severity Index climate record, the 20th century was the wettest century of the past two millennia in much of the Interior West, even accounting for notable drought cycles of the 1930s and 1950s. Context matters. Relatively high moisture during the 20th century facilitated reduced burn incidence. With this context, lower elevations tend to burn much more frequently that upper elevations. Where mixed-conifer or spruce-fir communities predominate and blazes occur every 200-400 years on average; change related to short-term climate shifts or fire suppression may have little ecological impact.

Different forests burn differently. The industrial reach of modern forest management dwarfs localized efforts by Native Peoples to modify landscapes via fire and cultivation. Accessible 20th century forests, generally lower, drier, and of mild slope angle, provided the initial inroads for wood harvest and fire protection which later encouraged recreation and home-building on private lands. These woodlands have experienced the greatest transformation. Homogenous forests closer to established developments are the frontlines of contemporary fire management. Such scenes supply flashy footage for nightly news broadcasts. The tragedies are real, but the roadmap for our arrival at this place was predictable and preventable.

A Plan for Island Park, Idaho?

Many rural communities in the West aspire to fire protection. At the same time, a belief in unlimited development dominates municipal planning. Island Park, Idaho stands out in that, unlike most amenity focused destinations, modest income levels drive much of the community’s decisions about wildfire protection. This is not—or not yet—an area of imported wealth, swelling tax revenues, and glamorous entertainment options. There is no nearby high-capacity airport. Instead, generations of cabin dwellers within a few hours’ drive make up the majority of residents.

A small fraction of Island Park’s 18,000 dwellings are occupied year-round. There are around 800 full-time residents. Cabins are modest and thick forests abut most homes across this volcanic bowl bordered by Yellowstone National Park on the east, Montana’s southern border to the north, and lowland sage-steppe on its western and southern margins. With such attributes, both daunting and dazzling, residents have laid claim to their small patches of private land and built a loose assemblage of homes—collectively a municipality, of sorts—from which they now must respond to the inevitable future firestorms.

The political climate, decidedly libertarian, makes implementation of civic fire protection logistically challenging. A 2013 poll by Resources Media found that only 29 percent of Island Park citizens were willing to take actions, such as thinning trees adjacent to homes; even fewer were on-board with replacing roofs with fireproof materials or widening access roads to dispersed cabins or concentrated developments. Since the community survey, efforts have congealed somewhat around a working group known as Island Park Sustainable Fire Community (IPSFC).

Similar municipal groups advocating for “Firewise Landscaping” are common in fire-prone communities. Recommendations call for homeowners to establish a continuum of active forest management, with more work closer to buildings.

“A small fraction of Island Park’s 18,000 dwellings are occupied year-round. There are around 800 full-time residents. They have laid claim to their small patches of private land and built a loose assemblage of homes—collectively a municipality, of sorts—from which they now must respond to the inevitable future firestorms.“

In Island Park, the consortium of individuals, homeowner’s associations, civic leaders, and federal land managers (that is, IPSFC) is making progress, though they face physical, economic, and political challenges. Fire protection merged with forest restoration is expensive. In Idaho in 2022 the State received $1.23 from the federal government for every tax dollar paid, but it is unclear how much of that is directed toward Firewise practices. This highlights the irony of staunch individualism in places that take in more federal money than they give, particularly where citizen protection is a first principle of government.

Nonetheless, actions taken to date include setting up volunteer-run demonstration projects, gaining government grants to clear a wide swath of lodgepole pine along the main highway US 20, acquiring flashing highway signs to alert people to combustive conditions and evacuation plans, and improving municipal codes regarding defensible space, sprinkler requirements, and access road improvements.

The IPSFS fully admits, however, that enforcement of these regulations has been nearly non-existent. The group recognizes other shortcomings, pointedly phrased as goals: to ensure multi- and single- unit rentals are included in fire prevention and safety procedures; to connect developments with loop roads rather than with one-way access; to create social media outlets for preventative actions and emergency communications; to plant fire-resistant plants and encourage aspen rejuvenation where it already exists; and to greatly increase civic education to inform people of why and where the Forest Service is removing trees.

Even though homeowner compliance is sluggish, the working group has expended considerable energy identifying regional environmental groups to “address resistance of groups that litigate” and “fight against environmental groups who are preventing vegetation treatments.” These quotes are telling: local residents see such “outside groups” as a central part of the forest management problem. However, this battle may be misplaced in terms of overall effectiveness in Island Park fire mitigation. Resistance from residents in the form of strident individualism and opposition to community action likely plays a more central role in this drama than interloping environmentalists.

Acknowledging A Key Word: Limits

In early June 2022 I toured Island Park by foot and vehicle to gain a sense of the fire prevention setting. Newer, more prosperous neighborhoods show some broad protective elements. Though seemingly out of place is this mostly wildland setting, bluegrass lawns, exotic nursery stock trees, and sculpted shrubs lined wide asphalt access roads and driveways. These modifications will slow flames in developed spaces. However, even here, there were some features that increase the likelihood a house will burn: native conifers overhanging wood decks, thick carpets of shed needles, and firewood stacked against exterior walls. I came upon one homeowner actively trimming the lower branches of a lodgepole pine near his garage. When asked whether he was taking other actions, he was circumspect about talking to a stranger but confirmed my observations: “It’s every man for himself. I can barely keep up on my own property.”

“I came upon one homeowner actively trimming the lower branches of a lodgepole pine near his garage. When asked whether he was taking other actions, he was circumspect about talking to a stranger but confirmed my observations: ‘It’s every man for himself. I can barely keep up on my own property.’”

Passing through an older and decidedly more haphazard grouping of homes, the scene was eye-opening. Here, narrow rutted roads—some paved, some not—are infringed upon by overhanging shrubs, capped by canopies of dense conifers. Small homes, cabins, and outbuildings abut forest in every direction; propane tanks and wood caches seem tethered to each property. Many of these cabins were likely built in an era very different from the dry, hot, fire-prone, and peopled forests of today. To the trained eye, it looks like a tinderbox.

When a settlement overextends itself into wildlands, the motivation is two-parts profit and one-part aesthetics. Our nation, in many ways, appears to be at a crossroads: one avenue says “more, more, more” toward increasing disfunction, while the other path preaches nature’s limits, earnest dialogue, and adaptive action.

While the West of lore seeks to reap short-term profit from nature, the region’s community-builders, the “stickers” in the parlance of Wallace Stegner, craft a life among these storied vistas through persistence and cooperation. The latter, as entrepreneur, is here to make a living, while the former, the so-called “boomer,” strives for a killing. The famed essayist Bernard DeVoto described this as the perpetual fight of ‘The West against itself.’ In a 1947 essay so named, he summarizes: “The West has always been a society living under the threat of destruction by natural cataclysm and here it is, bright against the sky, inviting such a cataclysm.”

The maxim holds that if floodplains flood, we shouldn’t build in them. But the forest corollary does not appear to hold water. Public polling of the Island Park community found that most residents felt that wildfires could and should be prevented, though the means of doing so were not explicitly stated. Further, half of respondents felt that saving their homes was the job of firefighters and, if their homes were damaged or destroyed, their insurance would cover replacement. The sentiment that fire, a native element of Western forests, can be stopped in its tracks may be attributed to decades of command-and-control messaging, as well as ample doses of cognitive dissonance.

A flare-up in lodgepole pine, boosted by even modest winds, burns at high intensity and may transform from spark to blow-up in under an hour. The challenge remains, here and elsewhere, how to spur collective action when environmental constraints run into Western mythology.

We should embrace strategic planning and slow the rate of development. Budding fire protection measures in Island Park are slowly gaining traction, but clear-eyed acknowledgement of limits to growth in the face of expanding drought, naturally combustible environs, and already overtaxed fire protection personnel will be essential.

“We should embrace strategic planning and slow the rate of development. Budding fire protection measures in Island Park are slowly gaining traction, but clear-eyed acknowledgement of limits to growth in the face of expanding drought, naturally combustible environs, and already overtaxed fire protection personnel will be essential.”

In an earlier career I made a living as a Forest Service nomad. We moved from north to south, border to border traversing states, surveying all landownerships with small field crews documenting ecological indicators of forest conditions. I witnessed the dangers of prone communities. In one blaze,

14 women and men lost their lives as that fire exploded beneath them carrying smoke and flames up a long steep gulch in an unimaginably hot whirlwind. Billowing black-brown plumes 45 miles away could be seen from my destination; the fatal outcome was later confirmed.

This was not the first, nor the last, of such tragedies in the name of… it’s never quite clear what. First it was watershed protection, then it was timber, then it was structural defense. Slogging through this endless war on fire, for those in actual combat, we might toss in bravado, ego, dominion, summer income, and adventure. Following on these motives, an undertone of good versus evil prevails. The inherent sensationalism of searing flames projected across the TV screens is seductive. Fire ‘the villain’ is an easy sell. Who’s going to save defenseless Bambi, much less our cabins, from Satan’s marauding furnace? An orphaned New Mexico bear rescued from a smoldering snag and now wearing jeans, a ranger hat, and holding a shovel strutted into the role like a marketing natural!

The dream of a flame-free forest, bolstered by interventionist practices, should be quietly put to rest like so many smoldering embers under autumn snow. Such prescriptions entail a healthy dose of humility.

Messaging is key to living with fire. Cataclysmic storylines about modern “mega-fires” lead to the mistaken impression that human building and agricultural forestry are not culpable. Moreover, it’s negligent to claim that fires have not been a historical fact of Western life.

Some in the media continue to cast wildland firefighting in military terms, as if an enemy or villain—Nature herself—must be vanquished. “Messaging is key to living with fire. Cataclysmic storylines about modern ‘mega-fires’ lead to the mistaken impression that human building and agricultural forestry are not culpable. Moreover, it’s negligent to claim that fires have not been a historical fact of Western life.”

Someone viewing today’s fires in a short-term climate window of 30 years against a backdrop of dollar value impacts would conclude that today’s fires are worthy of a rash response. What’s really new is the growing number of structures, and sometimes lives, in the path of predictable flames. Feed this basic script to news outlets, however, and the resultant language looks like “devastation,” “destruction,” “loss,” “charred,” “tragedy,” and on and on. Such dire branding may drive us to despair or inaction.

Rather than inflammatory language, we should kindle conversations based on ecological opportunity and social connection with wildlands. Strategic thinking grounded in complexity, preparedness, and acceptance of the unpredictable will be crucial.

Island Park typifies a Western version of American Dream, of living within nature. This locale, not unlike others in surrounding states, caters to those already residing in the region who desire respite from their workaday lives.

The paradox of the West’s various fire-exposed Island Parks is that while they may be more numerous than the famed resort towns, they exist outside the limelight, without the resources, planning, and infrastructure needed to protect them from the next firestorm. Often such commonplace retreats in the rural West value simplicity and independence when foresight and community are needed. As outsiders, bearing the best of intentions and armed with scientific knowledge, we are likely to be spurned. How might we all enact a bigger vision that incorporates acknowledged limits to growth while living with fire?

We can start with a clear-eyed civic understanding that we cannot stop fire and that, in many instances, we need fire for healthy landscapes. And we must come to terms with unrestrained development. Modern real estate and related industries, along with consumers’ endless demand for more, are out of step with our shrinking planet. As for wildfire, it’s not unreasonable to suggest the planet is pushing back. Humility suggests we listen, take note, and ask key questions of ourselves. How does this Earth function? How do forests thrive with flames? How can we live compatibly?

ALSO READ THESE RELATED STORIES:

New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife

Next Door To Island Park: Meet The Real Madison—And Why It’s Called ‘A Mini-American Serengeti’

A Success Story Of How A Development Threat Went Away On The Flanks of Henrys Lake

NOTE TO READERS: Paul C. Roger’s entire essay is well worth the read and is among a collection of stories about the West in A Watershed Moment. Read our story about the book and interview with one of its editors, Robert Frodeman, by clicking here. Support your local bookseller and buy a copy of A Watershed Moment from them.