by Todd Wilkinson

Sprawl is obviously not a new phenomenon in America. In many ways it is, in fact, a manifestation of our national identity—we being a country of individuals who struggle to accept limits imposed on property rights, livelihoods and lifestyles.

For much of the 20th century, sprawl was seen by many planners and boosters of commerce as a key indicator of economic prosperity, based on the well-worn but disproven theory that if a community isn’t growing in geographic area, then it must therefore be dying.

Today, sprawl is rapidly transforming a vestigal corner of the rural West that represents the pantheon of large landscape conservation in the Lower 48. Myths supporting sprawl are running headlong into a different reality, that when development expands across a landscape unchecked, the fabric of nature does not thrive, but withers.

When the casualty is Yellowstone, perhaps the best-known wildlife preserve in the world and a national treasure, it’s a problem of broad interest. Ironically, it’s a conundrum being exacerbated by an instinct—reversing decades in which many lonesome parts of the West were emptying out of residents and visitors—involving people yearning to “get back to Nature.”

What few younger generations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem may realize, and this includes the staffs of most conservation organizations, local governments, federal agencies, real estate firms and news outlets, is that ample warnings about sprawl’s advance have been sounded for decades.

What few younger generations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem may realize, and this includes the staffs of most conservation organizations, local governments, federal agencies, real estate agencies and news outlets, is that ample warnings about sprawl’s advance have been sounded for decades.

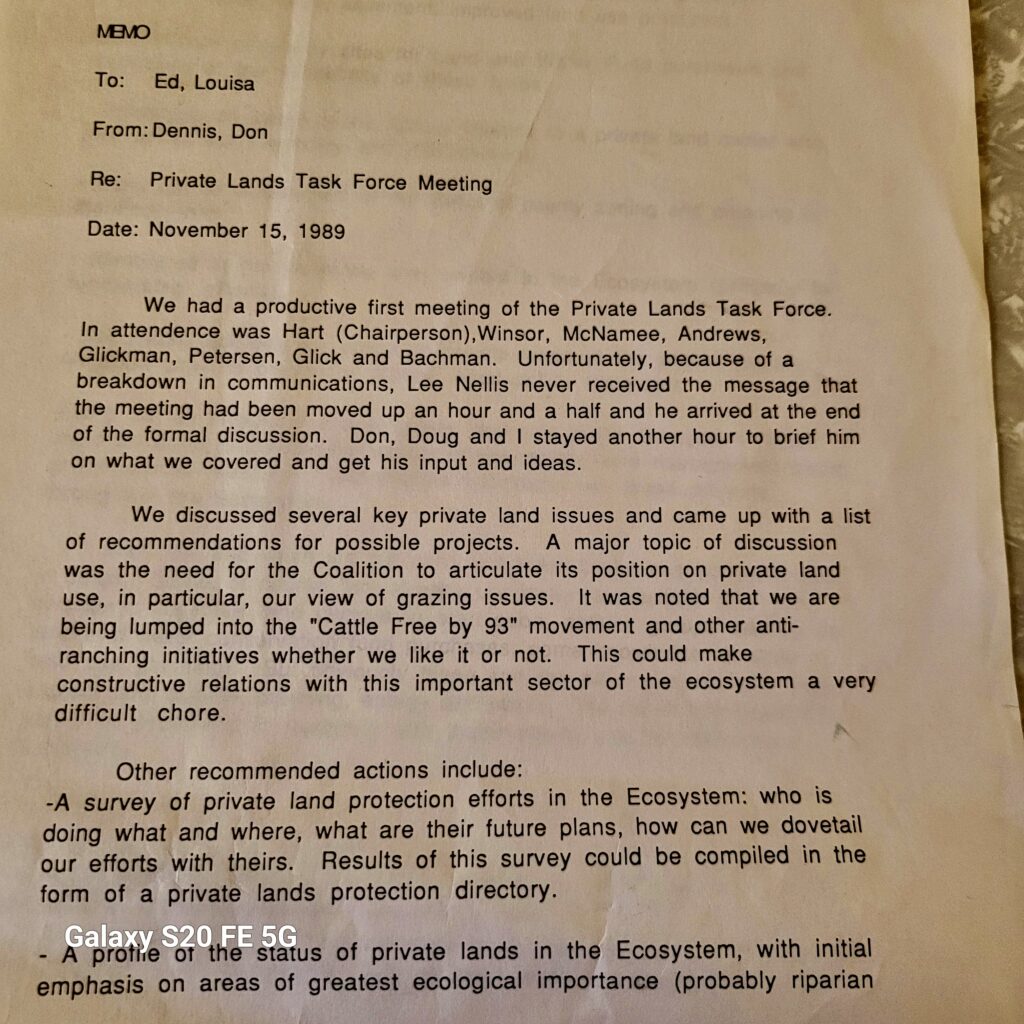

In 1989, 36 years ago, a then mid-career conservationist named Dennis Glick, working for the World Wildlife Fund, was hired by the Bozeman-based Greater Yellowstone Coalition (GYC), then headed by executive director Ed Lewis, an attorney by profession who had previously practiced law in Phoenix. Lewis had witnessed the deluge of migrating Snow Birds from northern states inundating the Sonoran Desert, and he was keenly aware of what unmitigated sprawl portends. He and his late wife, Wendy, wanted to raise their daughters in a more down-to-earth setting.

GYC in those days was hailed for its courageous mettle, a group founded out of urgent realization that one of Greater Yellowstone’s most enduring emblematic species, the grizzly bear, might vanish. The risks were highlighted in a benchmark report prepared by the Congressional Research Service in 1986 and it’s a compelling read. That same year, scientist William Newmark published the first in a series of peer-reviewed analyses warning about national parks, especially large ones in the West, and their wildlife suffering from forces beyond their borders. “With an increase in human population, energy and land development in the western United States and Canada, there is a potential for considerable habitat disturbance and change on the lands surrounding the national parks,” he wrote. “Existing parks may become true habitat islands unless an active effort is make to manage cooperatively the public and private lands that adjoin the parks.”

During Ed Lewis’ time at the helm of GYC, the group established a reputation for having a small staff that tenaciously battled against corporate entities monetizing Greater Yellowstone’s public land riches and treating the region as a natural resource colony.

Glick was selected from a pool of experienced applicants to lead a brand new multi-near initiative for GYC called “Greater Yellowstone Tomorrow.” The project was underwritten with a large grant secured from a major Minnesota-based foundation that understood the importance of planning ahead. At the time, coming into vogue was a vague concept called “ecological footprint” that provided a way of thinking about how humans, and the land consumed to support material lifestyles and business enterprises, can negatively harm nature, rural culture and wild ecosystems. As one might expect, affluent people consume far more space and raw materials, per capita, than those at the other end of the socio-economic scale.

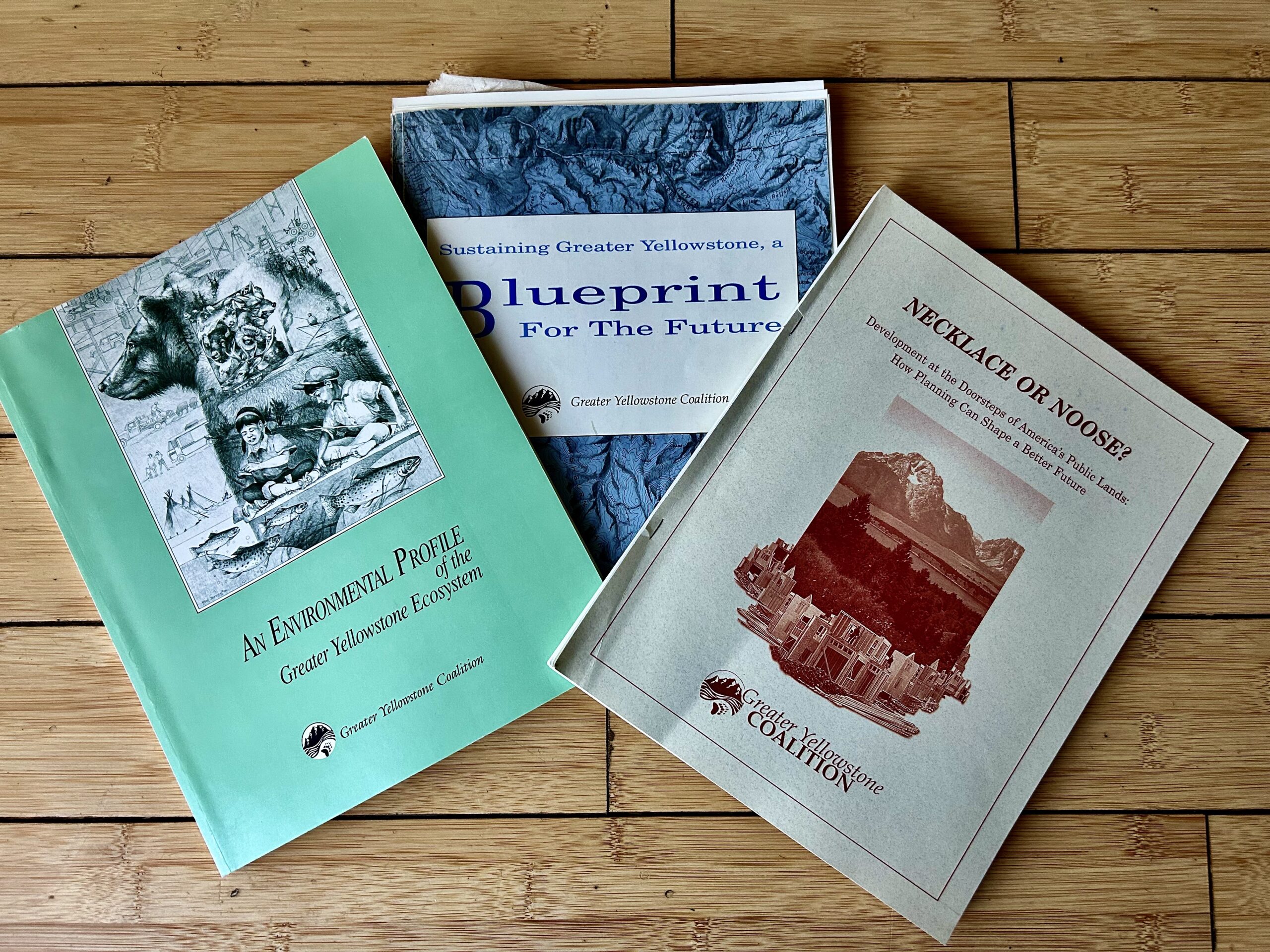

Part of Glick’s efforts produced two documents. The first, released in 1991 and co-authored with ecologist Mary Carr and wildlife biologist Bert Harting, was a richly annotated 130-page volume called An Environmental Profile of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that provided a snapshot overview of the region. It, in turn, laid the groundwork for a 222-page assessment titled Sustaining Greater Yellowstone: A Blueprint for the Future published three years later. That forward-thinking document drew upon the perspectives of leading experts in planning, land use and conservation biology to identify what serious issues this world-renowned bioregion would be facing decades from then. Unprecedented, it was even cited by the premier global conservation organization in the world, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) which recommended that it be a reference point for bio-regional planning efforts elsewhere.

A key component was a “science council” that in addition to comprising water, forest and soils specialists, had a heavy composition of experienced ecologists. [Full disclosure: this journalist was enlisted to write some of the case studies that involved interviewing those experts and what members of the science council said resonates in the reporting I do today].

What Glick and those advising him imagined nearly two human generations ago were exactly the wicked-problem issues the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is contending with now—the biggest being a radical shift away from most of the biggest threats happening on public land to instead occurring on private land.

Glick was no newbie when it came to pondering sensitive natural areas endangered by rapid change. Fresh off a tenure overseeing community conservation efforts in Central and South America that included working to incorporate indigenous people into park management and protection decisions, Glick quickly distilled emerging trendlines in Greater Yellowstone. His observations proved to be prescient—if not conservative given accelerating human pressures now intensifying in the region. To see for yourself how remarkably accurate the thinking was, go to the end of this story and read two pages of an internal memo written on November 15, 1989 by Glick and GYC’s then associate program director Don Bachman to Lewis and GYC program director and conservation firebrand Louisa Willcox.

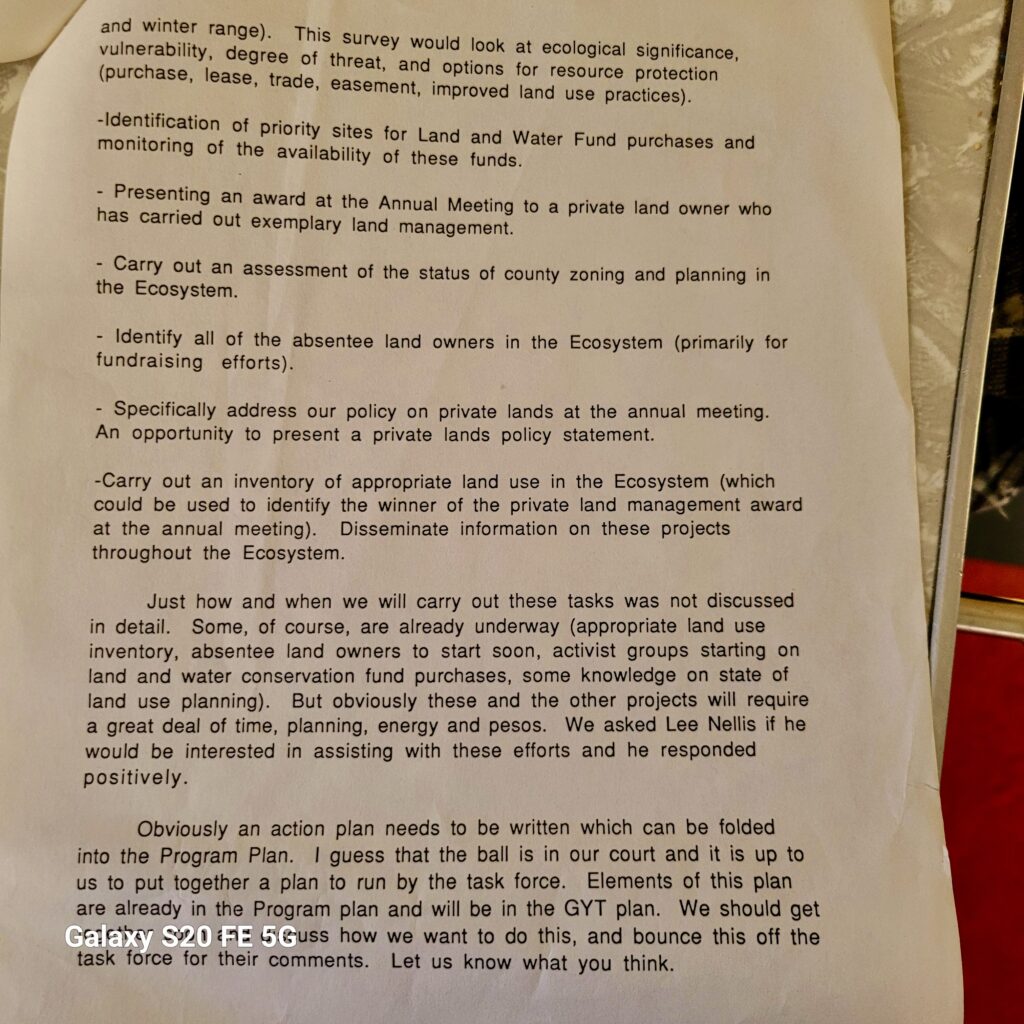

In it, Glick and Bachman write about a “Private Lands Task Force” being convened to address growth issues rapidly gathering on the horizon. Notable is how the Greater Yellowstone Coalition then played a central role in organizing a strategy to identify private lands critical to maintaining wildlife, open space and river corridors, working closely with ranchers, farmers and private property owners, and doing a comprehensive assessment on where the 20 counties of Greater Yellowstone were with planning, zoning, and having a framework in place to confront growth issues. The lands were more than just identified, however.

There was a clear understanding of the limits of voluntary and incentive-based conservation, the challenges facing multi-generational ranching and farming families to persist and the fact that outside developers, endowed with cash and legal teams, commanded swagger in convincing counties to approve their projects.

At the time, GYC pondered a number of strategies that could be applied to save private lands from ruin and one was having an attorney on staff. GYC also was the bulwark behind efforts pushing federal land management agencies arrayed together as the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee (comprising the National Park Service, US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service and BLM) to adopt a unified vision for conserving wildlife that transcends differing artificial administrative boundaries and mandates. Public land managers in the region were routinely chastised for their “silo thinking” and missions that were often at odds with each other. The most notorious example was how the Caribou-Targhee National Forest approved the largest single multi-decadal timber sale in the history of the Lower 48 that resulted in a clearcut extending many miles along the western boundary of its neighbor Yellowstone National Park.

John Mumma, forester of the Forest Service’s Northern Region, was initially optimistic a new era in true ecosystem planning could be ushered forward. In a Public Land and Resources Law Review article he co-authorized titled A Vision for Yellowstone’s Forests, he proposed that an administrator be tasked with creating a vision that prioritized protection of ecological processes that flow across public and private land. Mumma told me at the time that critical was bringing in counties to be part of the vision. It came on the heels of the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee publishing a 74-page draft document titled A Vision for the Future: A Framework for Coordination in the Greater Yellowstone Area.

But those efforts met resistance and ultimately were scuttled by politicians, county commissioners and anti-government voices who insisted (wrongly) the economic future of the region depended on extracting raw materials. Important to mention is that the Forest Service and BLM refused to use the term “ecosystem” instead of “area” because politicians thought it sounded too green. A concise analysis of why that fell apart was written by Dr. Susan Clark, an adjunct professor at Yale University and co-founder of the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative headquartered in Jackson Hole.

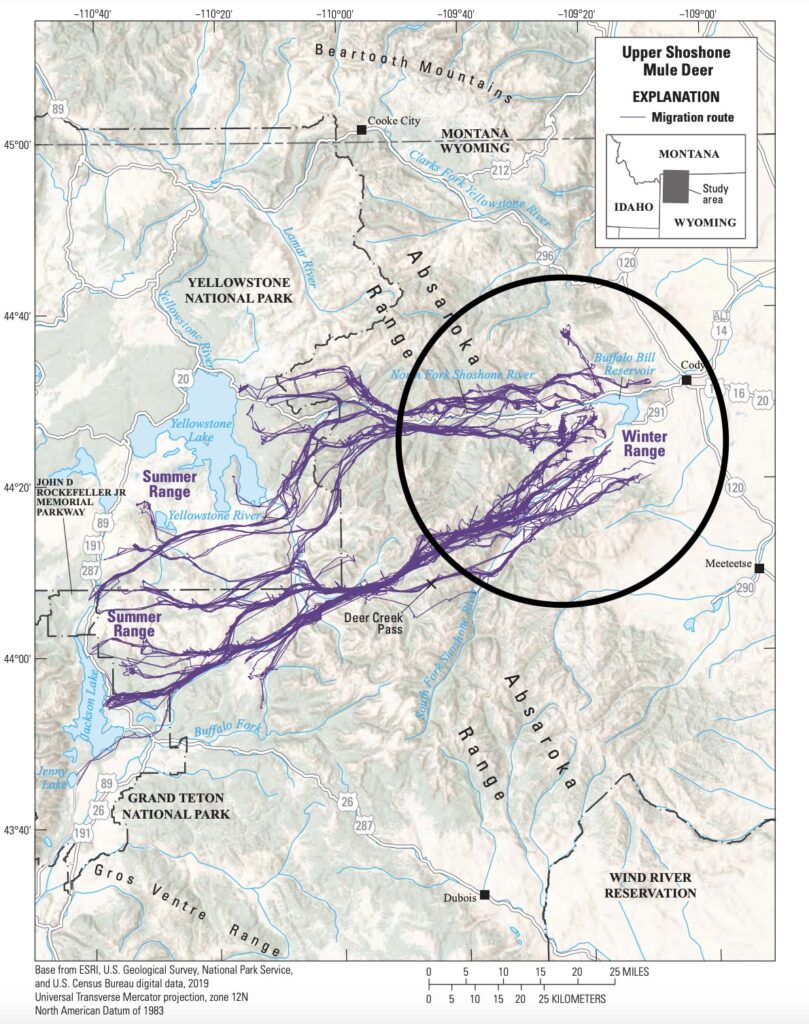

Stunningly, a sense of urgency existed within Greater Yellowstone’s NGO community around confronting sprawl—more than today. This was at least 15 years before wildlife researcher Hall Sawyer started studying the movements of mule deer in Sublette County, Wyoming, gleaning insights that has helped transform human understanding of wildlife migrations for many species in Greater Yellowstone. Emerging from that is recognition that sprawl on private lands, and conversion of ranches to rural subdivisions, can be as imperiling to a migration corridor as energy development and other natural resource extraction activities on public land.

For years, Glick had been based in Honduras and Costa Rica, the latter a nation renowned for its biological diversity (especially creatures smaller than jaguar and caimans). Billions of dollars have been generated over decades on the strength of nature tourism driven by bird watchers. Costa Rica approached the establishment of protected natural areas as being vital to safeguarding its cultural heritage and the economy.

Even though the Greater Yellowstone Coalition and national environmental groups (such as The Wilderness Society, Sierra Club and Natural Resources Defense Council among others) were, during the 1990s, focused primarily on public land issues involving threats posed by traditional resource extraction, Glick and others, including economists Thomas Power at the University of Montana, Ray Rasker in Bozeman, and ecology professor Andrew Hansen at Montana State University, saw a seismic transition under way. Rapidly emerging was a new industry, driven by an onslaught of newcomers also tied to natural resource consumption but fueled by humans—remote workers, Baby Boom retirees and people living on investments— seeking a higher quality of life in closer proximity to wild nature.

“[Confronting sprawl] is the gaping hole in how we think about protecting ecosystems, the elephant in the room that’s right in front of everyone but conservationists, who normally position themselves as watchdogs, don’t like to talk about it. Private land development is just not subjected to the same depth of opposition, habitat protection standards and evaluations that happen on federal and some state public land.”

—Scientist Leon Kolankiewicz who has spent much of his career analyzing how sprawl negatively affects wildlife and rural landscapes. He is also lead author in a new report on sprawl in Greater Yellowstone

One aspect was a gold rush to develop real estate on private land and convert former rural farms and ranches into recreation hunting and fishing properties, resorts and subdivisions; another was outdoor recreation on public land supported by an expanding infrastructure often located on private land. Picture ski resort communities like Teton Village in Jackson Hole, Grand Targhee on the west side of the Tetons, Big Sky and Bridger Bowl near Bozeman where sprawl has erupted around their base. A catalyst was Robert Redford turning Norman Maclean’s semi-autobiographical fishing fable, A River Runs Through It, into a movie, making demand for a cabin in the woods, set along a trout stream or a 20-acre ranchette with horses, as coveted as having a trophy home along a golf course.

Glick told me back then, in the early 1990s when I was a young journalist, that development on private lands—i.e. sprawl—had the potential to undermine a century’s worth of forerunning wildlife conservation on public lands that set Greater Yellowstone apart. Just as a clearcut on the Targhee National Forest or proposed geothermal development outside Yellowstone can negatively impact resources in the park, so, too, can subdivisions on private land.

At the time, such talk was often met with incredulity by many because the same things that had enabled wildlife conservation to flourish in Greater Yellowstone during the first half of the 20thcentury were still in place: geographic isolation, low human population, abundance of public lands, and vast sweeps of private land, mostly taking the form of undeveloped and working agrarian spreads located in river valleys between mountain ranges.

“All one needed to do, though, was study the historical patterns of sprawl, to imagine how the Front Range of Colorado and mountain towns were before they were ‘discovered’ or look at the explosion of the suburbs-exurbs then starting to expand north, south, east and west of Salt Lake City,” Glick said. “Greater Yellowstone had no magic repellent to stave off that eventuality, except the opportunity to plan ahead.”

° ° ° °

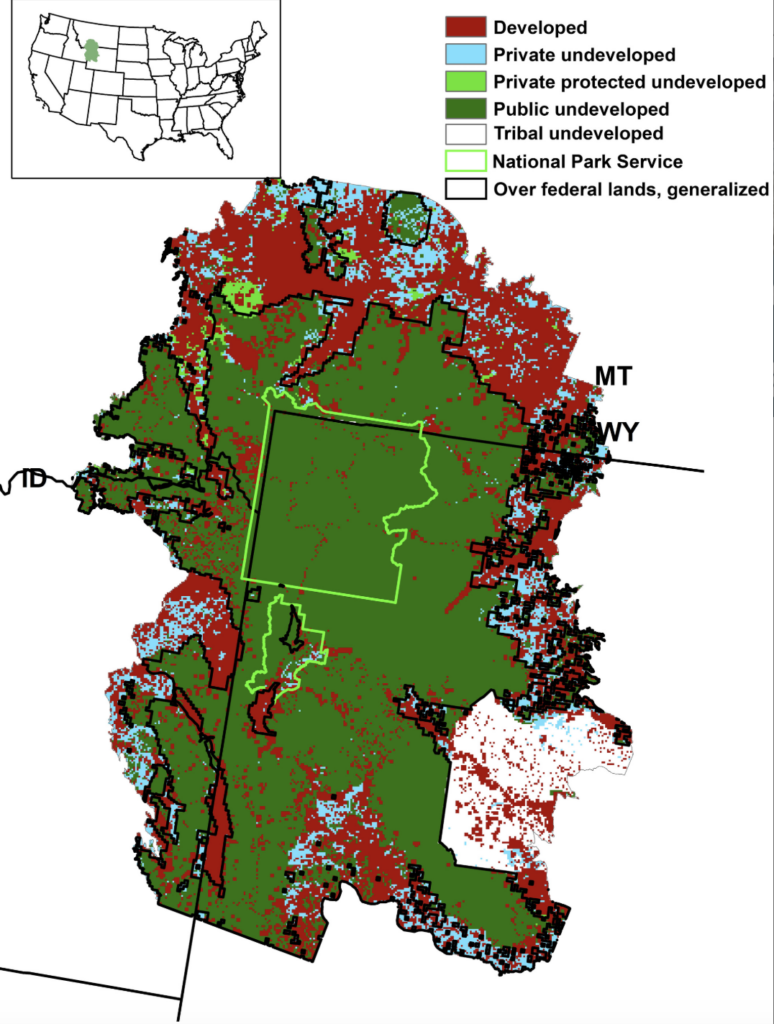

Famously, Greater Yellowstone has Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks in the geographic center and an encirclement of five national forests, three national wildlife refuges, large sweeps of BLM lands and the two-million acre Wind River Indian Reservation equal in size to Yellowstone Park. Of Greater Yellowstone’s roughly 23+ million acres, about one fourth of it—six to seven million acres—comprises private land. Like connective tissue and muscle holding together bones in the human body, it represents vital interstitial spaces between public lands and is critical to keeping the larger mass of ecological function together.

Why private land matters is that at least 80 percent of the wildlife in the ecosystem rely upon private land habitat, and, as research in Wyoming notes, so does the viability of ungulate migration corridors. Reflecting on what his team found in the 1990s, Glick today says recent decades and changes in technology (internet and cell phones transforming the ability to work remotely) plus expanded airline service have removed geographic isolation. Bozeman’s airport in the 1990s had a few hundred thousand enplanements annually; now it is over two million. A similar percentage of growth in the number of air travelers passing through Jackson Hole Airport (located inside Grand Teton Park) has occurred over the last three decades.

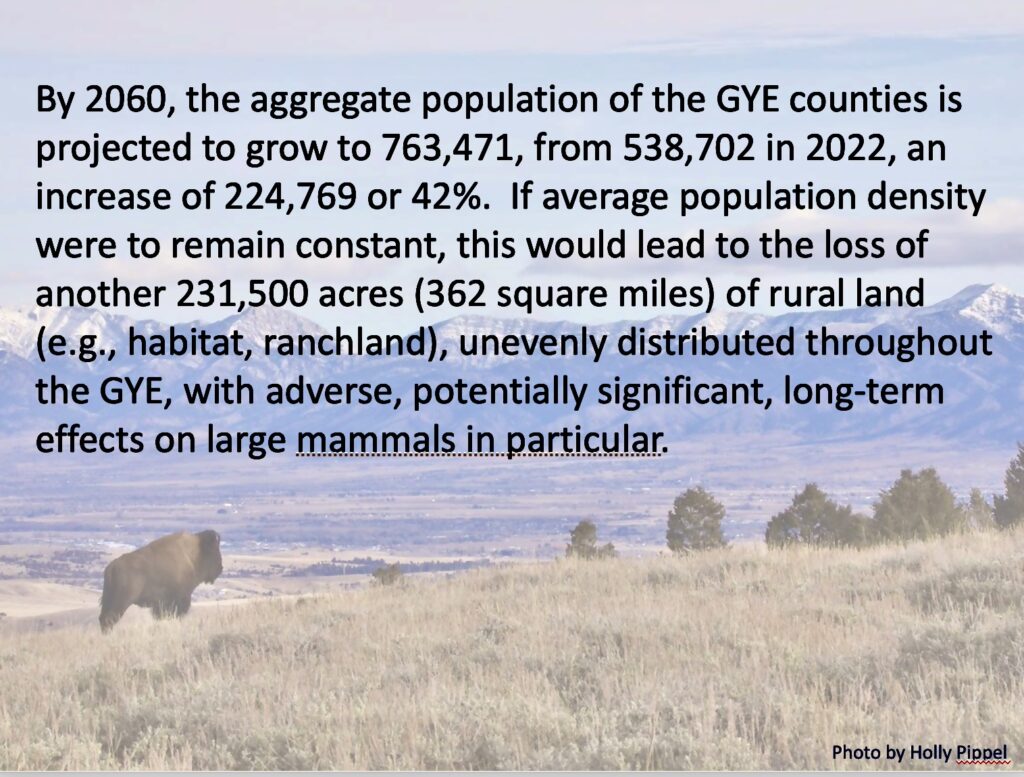

There was also a related synergy taking the form of a negative feedback loop. Population pressure resulted in fewer working ranches and farms. Sublette County in Wyoming and Madison in Montana were identified as being at great risk of habitat lost to rural land conversation. Ecologists Bruce Maxwell, Andrew Hansen and political science professor Dr. Jerry Johnson at Montana State University devised a forward progression model that predicted an alarming—and accurate—portrayal of how sensitive lands in Paradise and Gallatin valleys would fill up.

Since the 1990s, only the public land base has remained been relatively intact, with disruptions caused by things like massive natural gas development in Sublette and Lincoln counties near the foot of the Wind River Range and Upper Green River Valley outside of Pinedale. In addition to removal of the main factors that kept sprawl at bay in Greater Yellowstone, there are the deepening effects of climate change.

The trend of earlier, warmer, drier temperatures, documented for decades, are altering “normal” arrival of precipitation that affects everything from snowpack to river flows to crop yields and frequency and size of forest fires as well as the health of plant communities that reside at the bottom of the food pyramid, supporting wildlife, pollinating insects, agriculture and human livelihoods. Plus, nutrients from individual septic systems leaking into river systems already, coping with lower flows, have caused outbreaks of algae blooms.

In his ongoing analyses, conservation biologist William Newmark, mentioned earlier and a close friend of Glick’s, has noted that large national parks in the West are not big enough alone to sustain the health of wide-ranging species. The paper that made him famous appeared in the journal Nature in 1987. When habitat degradation occurs outside those protected areas, transboundary species over time dwindle in number and sometimes they vanish. That has happened around many large national parks in the West, and wildlife seen in Yellowstone and Grand Teton are vulnerable to the pattern, too.

Sprawl, as the Wyoming Game and Fish Department noted recently, has the potential to sever corridor lifelines for pronghorn and mule deer moving into Grand Teton Park from areas around the Upper Green River Valley and Red Desert in Wyoming. Read the excerpt of an essay by Dr. Matthew Kauffman of the Wyoming Migration Initiative and science writer Emily Reed at Yellowstonian that appears in the new book, A Watershed Moment, that discusses how sprawl creates pinch points for migration.

Robert Keiter, the Wallace Stegner Professor of Law at the University of Utah Law School has been fascinated by Greater Yellowstone’s enigma status and writing about it for decades. In 2020, he penned a scholarly overview of issues shaping the ecosystem published in the University of Colorado Law Review. It highlights private land growth issues. Read Keiter’s analysis by clicking here.

Keiter previously was a board trustee of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, but apparently GYC didn’t read Keiter’s overview that makes clear that the high volume of natural areas being lost permanently—and therefore the biggest threat to wildlife—are private lands. Citing research by Patricia Hernandez, Andrew Hansen, Ray Rasker, and Bruce Maxwell published in 2006 in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning, Keiter writes, “From 1970 to 1999, while the GYE regional population grew by a robust 58 percent, the area of rural land devoted to exurban housing increased by a stunning 350 percent, revealing the sprawling impacts of this growth on the landscape. This growth rate puts the GYE in the upper echelons nationally and greatly eclipses growth rates elsewhere in the three GYE states. The preferred development pattern has been large-lot rural subdivisions, which consume more land than denser development patterns. At the same time, the proportion of private lands converted to urban areas increased by 348 percent, largely at the expense of agricultural land.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________

“It wasn’t a question about whether sprawl would arrive in Greater Yellowstone and other valleys in the Northern Rockies,” Glick said recently. “But how fast, and how big would its negative effects be. The only entities that have tried to deny the negative consequences have been the real estate and development industries that have thwarted planning and talk of zoning at nearly every turn. There was widespread recognition then (in the 1990s) that the best possible strategy was being progressive in protecting healthy landscapes upfront rather than having to react defensively after the fact when they began to become impaired or unravel. Were we prepared and ready to handle what was coming?”

After a long pause, he continued, “Obviously, we weren’t. We aren’t. Wishful thinking doesn’t protect wild ecosystems. There was more urgency and vigilance 30 years ago than there is now. It isn’t that we didn’t have ample information. It’s that many different groups, including the NGO [non profit conservation] community, and with only a few exceptions, have not in recent years risen to the challenge to meet it. Certainly, not in the way they focus on fighting off mines and timber sales or advocating, along with the outdoor recreation industry, for expanded access into wild country.”

“The truth is that what’s happening on private lands is the biggest and most pressing threat to the ecological integrity of our public lands and stands to seriously harm the thing that symbolizes Greater Yellowstone’s greatness—its wildlife.”

—Dennis Glick, who led efforts for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Sonoran Institute and FutureWest to quantity the threats of sprawl and help devise strategies to keep wildlife and ranchers on the land

It’s important, Glick said, to stop bad resource extraction projects on public land, “but poorly-sited subdivisions can be disastrous natural resource extraction projects, too. And there are a lot more of them and they negatively affect a lot more surface area than any mine does.” Plus, he added, citizens are subsidizing rural sprawl. “In many ways, it could be argued that some groups have looked the other way, or claim they ‘only work on public land issues,’ giving themselves a pass not to engage in private land planning issues. But the issues are not separate, of course.”

Research by Bill Newmark, today based at the University of Utah, and others who delivered a new analysis in the journal Nature in 2023, make that clear. He highlights two bioregions bookended by national parks, Yellowstone to Glacier and Mount Rainier to North Cascades and notes how biological connectivity allows wildlife species to persist much longer than if they were confined to the borders of individual parks themselves.

“Ecosystems can only be protected when you think beyond and across artificial borders,” Glick notes. “The truth is that what’s happening on private lands is the biggest and most pressing threat to the ecological integrity of our public lands and stands to seriously harm the thing that symbolizes Greater Yellowstone’s greatness—its wildlife.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Above is the headline and opening paragraphs of a story that appeared in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle in April 2000, describing successful legal action brought by the Greater Yellowstone Coalition and Gallatin Wildlife Association to stop a proposed subdivision just beyond Yellowstone Park’s western boundary in the middle of an important wildlife migration corridor. The subdivision had earlier won approval from three commissioners in Gallatin County.

Zoning brings clarity and predictability for landowners, counties and citizens who don’t want to subsidize sprawl and want habitat wildlife needs protected, he says.. “Private land conservation work that focuses on planning and zoning isn’t easy but it’s the most consequential,” Glick explains. “If you are a conservation organization who touts yourself as being a leader, then you need to lead. If you’re sincere in your claims about wanting to save public wildlife, then you need to, at least, be as serious about protecting habitat, open space and river corridors as developers are in their willingness to exploit them.”

Glick says some groups have misplaced priorities and he cites a prominent example. Many groups today claim amorphously they are “working on climate change” and cast it as the biggest looming threat to Greater Yellowstone’s ecological health. While Glick and others say the impacts of climate change are indeed serious looking decades into the future, he believes it is drawing attention away from the most pressing—and addressable—transformative menace at hand: sprawl.

If habitat essential to both wildlife and agrarians isn’t safeguarded, many of the coming impacts from climate change expected to threaten biodiversity, agriculture, and tourism in Greater Yellowstone will be moot because the base of natural private lands will be permanently lost, he says.

In 2024, at an event called the Wyoming Sportsman’s Forum sponsored by Governor Mark Gordon, Jerod Merkle, the Knobloch Professor in Migration Ecology and Conservation at the University of Wyoming noted that 40 percent of elk winter ranges are found on private land. He pointed out that elk will avoid lands that are more than two percent developed. Grizzlies will stay away from rural property have a single home on a section of land—640 acres—and it negatively influences bear survival. Such skittishness likely applies to other species.

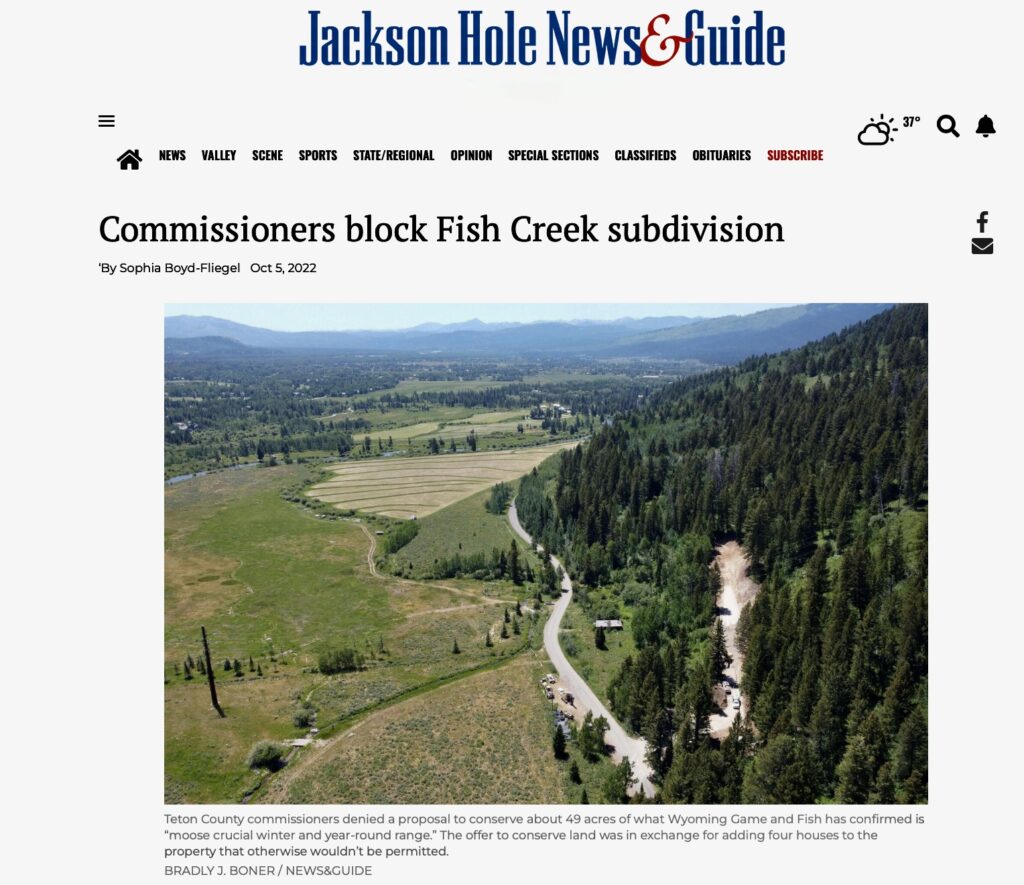

Bob Budd, who oversees the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust, told reporter Billy Arnold with The Jackson Hole News & Guide that proposals for new subdivisions are proliferating in Greater Yellowstone counties in Wyoming. In Park County, Wyoming outside of Cody, residents are becoming increasingly concerned about the change and some are doing what they can to secure the fate of their land by putting under conservation easement or taking advantage of incentives to protect wildlife or keep the land open. Budd told Arnold his Trust is reviewing 40 different proposals from landowners.

When Glick and a growing group of big picture conservationists assess how sprawl—not natural resource extraction on public land—represents the most formidable challenge for wildlife water quality, open space and sense of place, they wonder aloud: “Why aren’t there more groups taking it on now? Why aren’t the major foundations who fund them providing more resources to address it?”

Not long ago, a longtime friend who happens to be a senior grant maker working for a major funder of American conservation philanthropy told me “we gauge success on how many acres of public land we put in to the win column.” We love to have frank discussions. When I noted that putting a federal public land under a higher level of protection isn’t really a “win” but is simply an action that prevents its degradation and does not add more habitat, he went quiet. And then, when I noted that many acres of private land are being permanently removed from the ledger of functioning habitat in Greater Yellowstone every day than are receiving higher levels of protection on public land, I asked how the groups his foundation was funding were appreciably offsetting that deficit? He admitted that conservation groups in Greater Yellowstone need to up the level of their game—and fast. Perhaps, I said, they might take a cue from the past.

While at GYC, Glick was an active member of the Montana Smart Growth Coalition which staged two major conferences and brought in nationally-recognized experts to advise planners, elected officials and conservation organizations. He was a lead co-organizer of a GYC conference called “Necklace or Noose—Development at the Doorstep of Our Public Lands” on sprawl occurring around national parks. The event was held in the map room of Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone in the year 2000. GYC was involved directly with planning and zoning issues in several different counties and valleys and provided technical assistance to local groups.

GYC also filed lawsuits when needed to stop major developments proposed in sensitive wildlife habitat, including successful legal action that prevented a subdivision in Gallatin County near the west boundary of Yellowstone National Park. Not long ago, a leader of GYC said publicly that the organization has gone in a new direction and chooses to avoid litigation “Some local groups pooh-pooh lawsuits,” Glick says. “But sometimes lawsuits are the only course of action, and there’s a reason why there are environmental protection laws on the books and regulations put in place. If a conservation organization isn’t willing to make sure laws are enforced, which itself serves as a strong disincentive to developers who believe they can get by with almost anything, then what are those groups doing? Developers don’t usually respond to polite requests to do the right thing. Often they are compelled to act in accordance with the public interest either by force of law, public opposition or both.”

During his tenure with another group after GYC, Sonoran Institute —an organization founded by Luther Propst who today is an elected county commissioner in Teton County, Wyoming— Glick helped organize several “Successful Communities Workshops” in Greater Yellowstone towns, assisting residents and elected officials better understand planning issues—what works and what does not. Later, Glick founded FutureWest and also worked with ranchers in the High Divide Ecosystem. FutureWest held a conference on growth in Bozeman and it enlisted the late Dr. Brent Brock, a scientist who had done a number of studies on the costs of land fragmentation, and worked with Steve Primm who has spent years trying to reduce grizzly conflicts with ranchers.

“We don’t need to hold more meetings or establish more subcommittees or bring in more science because plenty of great data already exists. We certainly don’t need to be more naively wishful in telling ourselves that if we only talked more over cups of coffee and beers, we’d arrive at a better approach to land use planning and zoning. We have all the info we need. Lacking is the will to make hard but necessary choices.”

—Dennis Glick

“I was a participant in these efforts along with others, but sometimes we felt like we were blowing in the wind,” Glick says. He also was a member of scientists and planners convened to help Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks create guidelines that counties could provide to developers for how to minimize their negative impacts on wildlife. They are mere “guidelines,” he says, that developers frequently flout or ignore with little accountability coming from county commissioners and planning staffs.

Worth mentioning is that while with GYC Glick was the only staff member of a professional conservation organization in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem who showed up and testified at hearings held by Madison and Gallatin counties considering approval for the Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, Moonlight and other major developments at Big Sky. He warned about incremental cumulative effects, which today are writ large.

“There were a group of very dedicated people who realized the loom of sprawl and the threat it posed to mountain valleys in Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies. For the record, I was an early major proponent of consensus and collaboration models,” he says. “But history has taught us a hard lesson.”

Soft conservation approaches alone, as illustrated by consensus and collaboration, are insufficient to deal with the blitzkrieg of development pressure. Conservation easements brokered by land trusts with willing private land owners, he says, are excellent tools for rural valleys dealing with slow incoming growth and places that are isolated away from airports. “But they’re not keeping up with what’s being lost and we just need to admit that,” he says.

To Glick’s point, an analysis by Bozeman-based Headwaters Economics in 2024 found that between the years 2000 and 2021, low-density residential construction converted one million acres of undeveloped land in western Montana to sprawl, and many were located on lots greater than 10 acres, which scientists say displaces many species. Many of those acres were prime habitat for wildlife that are now displaced. That one million acres can never be restored and much of it is located in the Yellowstone to Glacier corridor highlighted by Newmark. Development happening on that one million acres, in turn, is, through a spillover effect, negatively affecting the ecological function of millions of acres of private and public land.

Several high profile development proposals illustrate how lack of county zoning leaves commissioners with fewer hooks to say no. The controversy in Park County, Montana over the recently proposed resort up Suce Creek, a proposed RV park near Raynolds Pass in Madison County, a planned upscale resort by billionaire Joe Ricketts, founder of TD Ameritrade, in Sublette County, Wyoming and proposals to build a hotel and airpark on Henrys Lake Flats in Fremont County, Idaho near Island Park are just a few examples.

Glick and colleagues at World Wildlife Fund had used consensus and collaboration models with their community conservation work in Latin America some four decades ago, which included creating protected areas where indigenous leaders were involved in planning. Those indigenous leaders, he notes, prioritized protection of nature and other species. He was an early champion of bringing consensus and collaboration to Greater Yellowstone three decades ago but today he is a critic.

“I’m not completely dissing consensus and collaboration because in some instances it is effective,” he explains. “One could argue that the creation of Yellowstone National Park was a form of consensus and collaboration and we today are dealing with the consequences of the park not being large enough to guarantee the survival of wildlife living in it. My criticism of recent consensus and collaboration efforts is that they seem more focused on appeasing the desires of human participants than achieving significant conservation outcomes which benefit wildlife and protect wildlands.”

In September 2000 at the Necklace Or Noose conference the Greater Yellowstone Coalition hosted, national experts on land use planning gave memorable presentations. I attended the event and the transcript from it makes for compelling reading. “Why is GYC, a conservation organization, concerned?” Glick asked aloud at that meeting as he and GYC’s then executive director Mike Clark were moderating panel discussions with noted American conservation biologist Dr. Reed Noss and Montana State University ecologist Dr. Bruce Maxwell.

“Even though private lands make up a relatively small portion of the region, they have disproportionate value,” Glick said at that conference. “Many are the richest habitats—ungulate winter ranges, riparian corridors, wetlands and other important habitat areas—are found on these private lands. Surveys of subdivided land and new homesites show that ecological hotspots are often preferred building sites.”

“Even though private lands make up a relatively small portion of the region, they have disproportionate value. Many are the richest habitats—ungulate winter ranges, riparian corridors, wetlands and other important habitat areas—are found on these private lands. Surveys of subdivided land and new homesites show that ecological hotspots are often preferred building sites.”

—Dennis Glick’s comments at a conference in September 2000 held in Yellowstone Park that featured national experts speaking about the threats posed by sprawl to wildlife in the ecosystem

Glick noted how a survey of land ownership found more than half a million acres of private land had been subdivided in Greater Yellowstone’s 20 counties as of the year 2000. “A lot of these subdivided lands have not yet been built upon. The stage is being set for some very dramatic changes in the landscapes of Greater Yellowstone.” (The number of subdivided acres has sharply risen around the ecosystem since then).

A person who heeded the warning was Bill Murdock, a Gallatin County Commissioner who said the perspectives of Maxwell, Noss and Montana State University professor Andrew Hansen, a landscape ecologist who recently retired, needed to be prominently featured before the public (including the state legislature) who didn’t grasp what was at stake.

Murdock fought many battles to bring countywide zoning to Gallatin County, which, in retrospect, would have blunted the deleterious effects of runaway sprawl as Gallatin became one of the fastest growing per capita in the West. But each time, Murdock’s efforts were beaten back by the real estate and development industries.

At the Necklace or Noose conference a quarter century ago, Noss said, “The GYE is still largely intact, despite all the problems you’ve been hearing about. However, many of us feel the next decade or so may represent our last chance to keep it that way.”

In 2018, just before Covid blew into the region like a welter, Andy Hansen and Linda Phillips at MSU assembled what they called a Wildland Health Index and their peer-reviewed work was published in the journal Ecosphere. They found that 31 percent of Greater Yellowstone had been developed and the noose around Yellowstone and Grand Teton’s necks was tightening between sprawl and network of trails and roads on public land.

“Rural homes more or less ring the public land on all sides of the park [Yellowstone]. It’s rather stunning to me to look at a map of all the homes that now surround the park. And changes in these private lands surround the park really influences what happens in the park,” Hansen told Smithsonian magazine in 2022. “Between all the development surrounding the park, and the increased number of pool who are recreating on public lands in and around the park, the pressures have built quite dramatically.”

Not long ago, Mike Clark, who served as executive director of GYC during two different stints, noted that GYC in the 1990s was primarily focused on fighting the New World Mine on Yellowstone’s doorstep, and consolidating public lands in the Gallatin Range. Those efforts were momentous, he said, but was a huge mistake to not ramp up the amount of staff resources devoted to watchdogging rural development around Big Sky, Bozeman, Jackson Hole, Teton Valley, Idaho, and assisting GYC’s affiliated groups in pushing for planning and enforceable zoning in Greater Yellowstone’s 20 counties.

He predicts the lack of engagement today by the large national and regional conservation organizations in local planning issues—combined with anti-planning efforts in state legislatures, some of which are even going after the validity of conservation easements—will be viewed in hindsight as a colossal failure and missed opportunity.

Thinking back and but looking ahead now, Glick says: “We don’t need to hold more meetings or establish more subcommittees or bring in more science because plenty already exists. We certainly don’t need to be more naively wishful in telling ourselves that if we only talked more over cups of coffee and beers, we’d arrive at a better approach to land use planning and zoning. We have all the info we need. We need to become comfortable talking about really uncomfortable topics and this is one of them. Lacking is the will to make hard but necessary choices,” he says.

To deal with sprawl requires making decisions that go beyond voluntary compliance with environmental protection. “That’s an approach which has a pretty abysmal track record. If developers believe they can save money and cut corners to avoid doing things to save wildlife habitat, they will. My criticism with the same conservation movement I spent decades of my life involved with, and proudly I should note, is that groups today are not willing to play the role of watchdog that resides at the core of their very missions. They are not meeting development pressure on private lands with the same kind of vigor and resources they direct toward opposing mining, logging, oil and gas drilling, and public lands livestock grazing. Why is that? It baffles me. If we can’t count on them, then who?”

_________________

BELOW: Some 36 years ago, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition was leading regional discussions about how to address the inevitable, incoming tidal wave of sprawl. The memo, below, was written in 1989 and mentions creation of a Private Lands Task Force. What was more being done to address sprawl two generations ago than is being done today?

TO READERS: Thank you for reading this latest installment of our ongoing series and investigative reports on the impacts of private land sprawl on wildlife, community and public lands. We appreciate your support.

Some other stories in Yellowstonian’s ongoing series of stories about issues related to sprawl

The Spillover Effects Of Big Sky’s Ravenous Appetite For More

On The Front Doorstep To Yellowstone, A Montana County Wrestles With How To Confront Change

New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife

What’s Facing The Madison Valley? A Longtime Conservation Land Broker Weighs In

Refusing To Surrender Wild Ground

Proposed Suce Creek Luxury Resort In Park County Is Just “Tip Of The Iceberg”