From the Editors of Yellowstonian

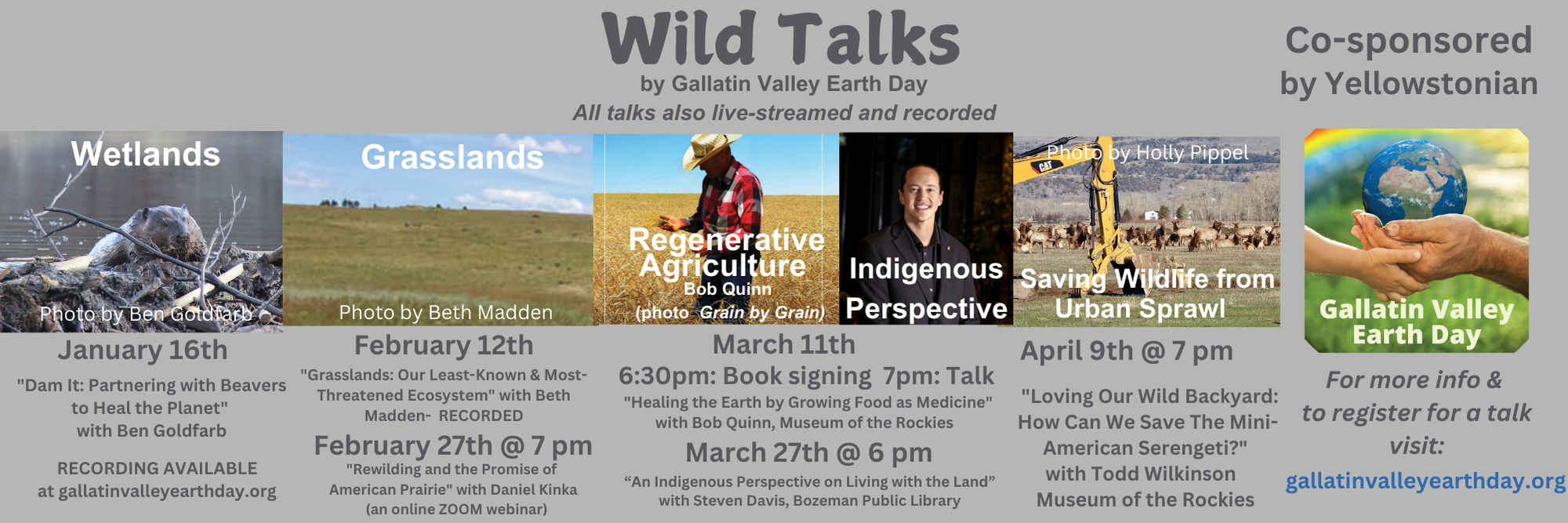

Were a landscape painter to invent such scenes, they would seem almost unbelievable. That’s why the photographs and videos here taken by naturalist Holly Pippel are so stunning. In place of her usual column for Yellowstonian, we’re sharing the photograph, above, and related videos, below, along with Pippel’s thoughts about autumn in the West and animals on the move from mountains to valleys.

Hunting ungulates in the Northern Rockies is a longstanding cultural tradition, the same as it is in most corners of the Lower 48. It’s impossible, in fact, to untether the connection between wildlife conservation that rose out of an era of unthinkable depletion to hunting, in modern times, representing a way for people to re-connect with their home bioregion and literally derive sustenance.

This does not mean that the taking of another life occurs in the absence of reflection and isn’t bittersweet. For Pippel, who has spent the last several years following elk, deer and other wildlife in all the seasons across the Gallatin Valley, the struggles that animals face with rural landscapes filling up with people have caused deep reflection, as well as compassion and heartbreak.

Pippel has an incredible eye for composition and capturing moments, It’s why many readers reach out to her asking to purchase prints of her work. Recently, a Pippel photograph of a bison standing along a ridge on Ted Turner’s Flying D Ranch overlooking the Gallatin Valley was selected for the cover of a brand new and unprecedented scientific study from NumbersUSA examining the ecological consequences of private land sprawl on Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife. Yellowstonian co-founder Todd Wilkinson, who has written extensively on growth issues in the ecosystem, was asked to pen the study foreword. To view the study, click here. The narratives that accompany Pippel’s videos below were written by her. Enjoy them. May they prompt you to ponder the importance of wild places in your life, and have deeper compassion for animals in your own backyard dealing with ever-greater human pressures.

Text and videos by Holly Pippel

As Todd Wilkinson posted on the Yellowstonian Facebook page, this scene, below, is like a dramatic cliffhanger and we don’t want to know how it might end for the wildlife in view. Elk are on the move in the southern Gallatin Valley and this video subtlety illustrates how members of the famous Gallatin Elk Herd are on a collision course with problems caused by explosive growth that is transforming the landscape. One of the places where it has become gravely apparent is along US Highway 191 leading from Four Corners and Gallatin Gateway, Montana south about 35 miles to the resort community of Big Sky. In recent years as traffic volume has swelled, hundreds of elk, mule deer and other animals have been killed in vehicle collisions, imperiling the lives of human motorists and causing property damage. The problem cannot be addressed through easy fixes. While I applaud the creation of proposed wildlife overpasses and underpasses in areas identified by the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, the bigger issue is wildlife being disrupted and having their lives upended by development overtaking seasonal habitat and migration areas. Look closely at the the video and you see a steady stream of commuters—thousands of construction workers, mostly, building homes for seasonal residents in Big Sky. Here, they are are heading north on US Highway 191 from their jobs. The workers must commute because they cannot afford to live in Big Sky and there’s a serious lack of affordable housing that will not be easily resolved through token gestures. Big Sky cannot develop itself out of the problem it has created for itself and development there already has exactly a huge toll on wildlife and habitat. On the right side of the video you can see a group of elk moving eastward from the Gallatin River toward US Highway 191 and many will attempt to cross. If the pattern repeats itself, many will die. This location also is not far from the site of a proposed controversial gravel pit south of Gallatin Gateway that will disrupt elk and other animals all the more. At what point will the wild essence of this part of Greater Yellowstone be lost?

Often, we lump wildlife into a generic category—just calling everything “wildlife”— when we are making decisions that affect the fate of many different species. Indeed, wildlife are not all the same. They comprise a rich diversity, including, in this part of the world where I live, elk, bears, wolves, coyotes, moose, deer and hundreds of others. Greater Yellowstone has the most intact and full complement of native terrestrial species remaining in the Lower 48. For any of us who spend time observing the magical array, we see individuals and each one has a personality. I have found that some are more vocal; they experience joy and sorrow. Some are more caring, many have a sense of humor (cow elk especially, along with foxes, coyotes and wolves). Some are grumpy or more serious, some more needy or more independent. Some are elders that reach the young how to forage, hunt and survive, and where to move across the landscape adhering to ancient routes that may be invisible to us. As rifle season approaches for hunters, I always prepare myself for the possibility that up to 50 to 75 percent of the elk bulls I see daily won’t be here anymore come winter. It’s a sobering reality, and, as an archery hunter myself, I understand the tradeoff. However, it doesn’t mean that I won’t have some somber days ahead. The biggest threat to hunting is proliferating human development. What hunters in many of the mountain valleys of Greater Yellowstone are beginning to understand is that sprawl negatively affects not only the quality of the hunt, but the survival of wildlife itself.

I love to be out for sunrise and stay out until the sun sets. This time of year changing camera cards can be tricky. The elk stay late and come back early. Fall winds are shifty. On the night when this scene, below, revealed itself, I thought I was in the clear as the elk were further west and in lower meadows. Just as I repositioned my camera, I looked to my left and 40 cow elk silently appeared 20 yards from me on a ridge. Thankfully undetected (me being in camo and with good wind direction), I leaned in on a tree and waited, frozen in place, 40 minutes, for 200-plus individuals to file by me. I can’t imagine the south end of the Gallatin Valley without them. They give it spirit. Save open space, squelch sprawl. Or we’re going to lose something that can never be replaced and future generations will wonder why we let it happen without speaking up? Is that how we want to be remembered?