by Todd Wilkinson

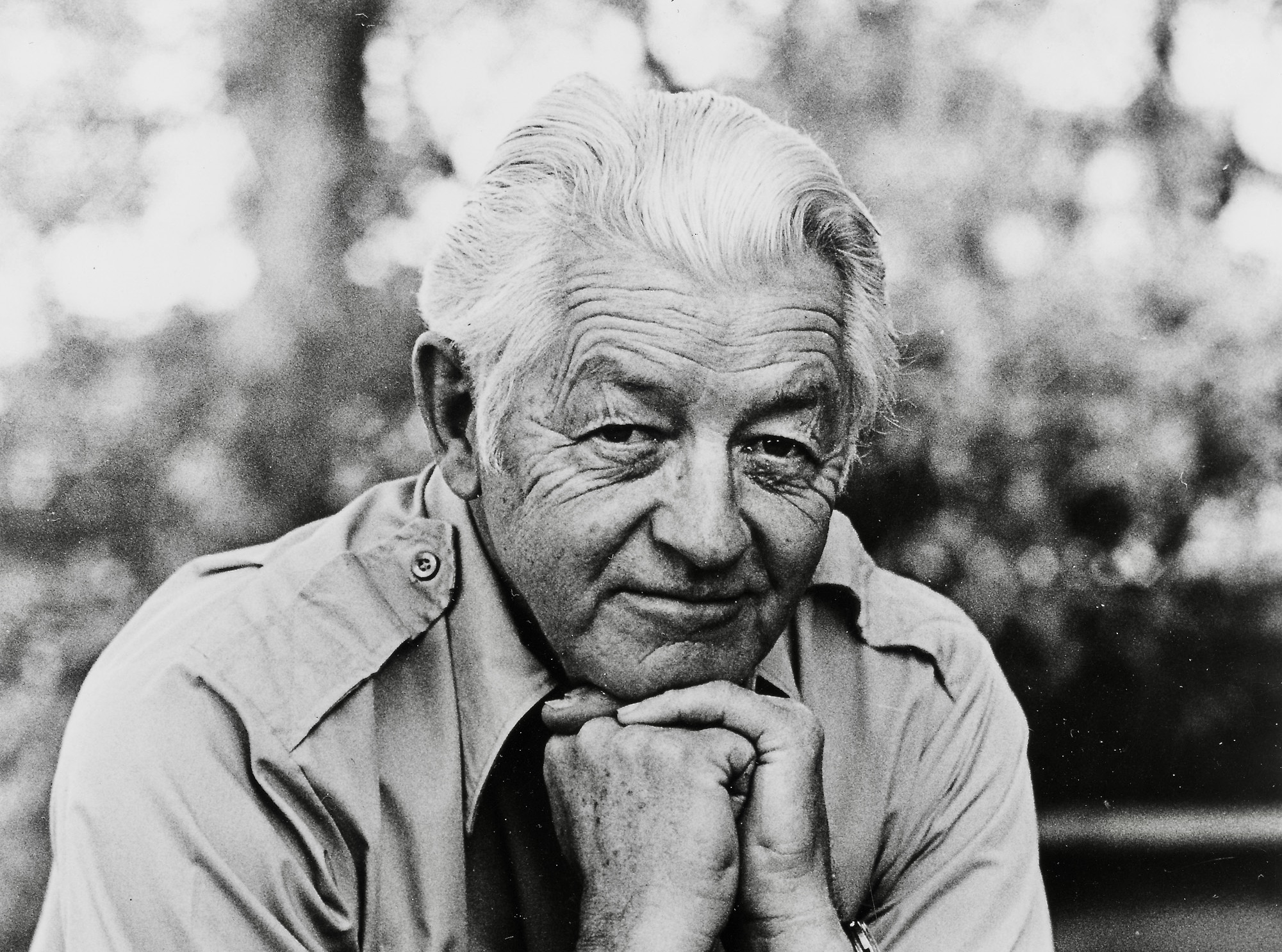

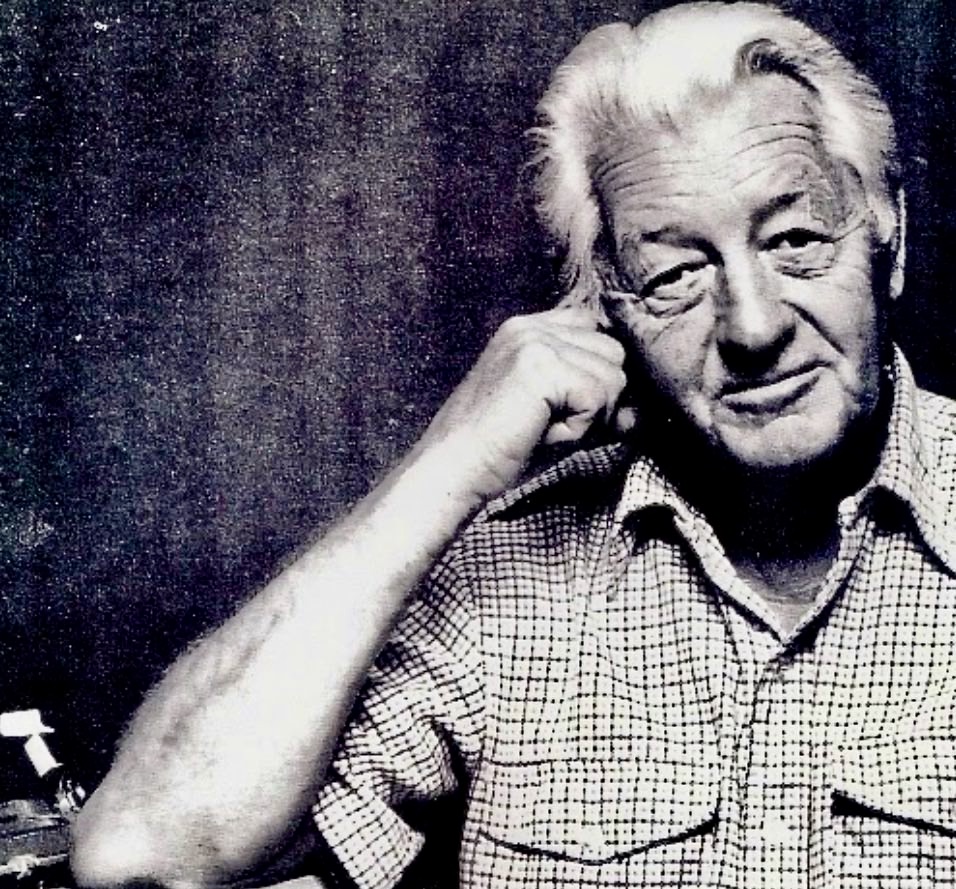

Of all the paragons of New West thinking, Wallace Stegner may be the most widely quoted. Famously, he observed: “National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.” He also called wilderness “the geography of hope.”

Today, in some circles, them is fighting words.

People like to quarrel and parse by assigning intent to turns of phrase that never were written to trigger. Allusions are taken out of context; individuals judged not by the times in which they lived but ridiculed for what they should have said or done, or how they should have acted. In hindsight, some historical figures in conservation are demonized and discredited for being imperfectly human or having not been saintly.

Among contemporary New West scholars, who often hail from Ivory Towers and places where long ago the ecological notion of wildness in their settings vanished, Stegner (1909-1993) and others are critiqued through such a lens. Often lacking in today’s culture wars is larger context and nuance, for it is far easier and lazier to cancel than engage in complicated, uncomfortable discussions about how the cause of saving nature involves mortal beings, none of whom, on any side of any issue, are without flaws.

Stegner, however, inhabits a special place in the canon of literature based in the American West and he lent his voice to conservation. Not only did he win both a Pulitzer Prize for Angle of Repose and National Book Award for The Spectator Bird, he held the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is high regard. To him, it possessed a rarefied status in the constantly evolving realm of what it means to protect the wild essence of a place.

A new book Wallace Stegner’s Unsettled Country: Ruin, Realism and Possibility in the American West ought to be approached and digested as a most thought-provoking read, no matter what side of a barbed-wire fence you stand on. One prominent historian, Tiya Alicia Miles, winner of the National Book Award, called it “unflinching” and indeed it is, at the very least, that. Another well-known observer, environmentalist and climate activist Bill McKibben, offers this praise, “Wallace Stegner was one of the greatest original minds America ever produced, and I think he’d be quietly happy to see his work expanded, challenged, and built on to great effect in this smart volume. It’s a very high tribute.”

There are many books that claim to take a deep dive into Western mythology but this one delivers the goods because of the diversity of writers represented. Twelve guest essays about Stegner and his notions, sandwiched between a Prologue and Epilogue, and edited by Mark Fiege, Michael Lansing and Leisl Carr Childers, are powerful. They’re as likely to stir conversation and debate, as they will reassure those already convinced of the author’s oracle status, or of his fallibility.

Stegner, who often told his protegees to write about what they knew and to draw upon their lived experiences and personal histories, never did much reflection, at least in print, on the undeniable, horrific consequences of genocide carried out against indigenous people. He saw plenty of pain, destruction and desperation in the settlers who poured into the interior West who, with little wherewithal about how to co-exist with the land, suffering the consequences of their own arrogance in believing they could force it into submission.

Yet another of his classics, Beyond the 100th Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West, is required reading in history, ecology and environmental study courses at universities across the country. It is a reminder of the perils that come with communities outstripping the ability of the land to sustain them, especially with water in the arid West.

What would Stegner make of the conservation movement that has emerged in the last 30 years since his passing? What would he think about groups that more often tout the virtues of industrial outdoor recreation over accepting limits on personal ambition in order to protect the last remaining shreds of wildlands? What would he say about sprawl sweeping across the formerly rural valleys of the Northern Rockies? What would he say to the groups who nowadays seem to be retreating from—or ashamed of—even having the world “wilderness” in their name?

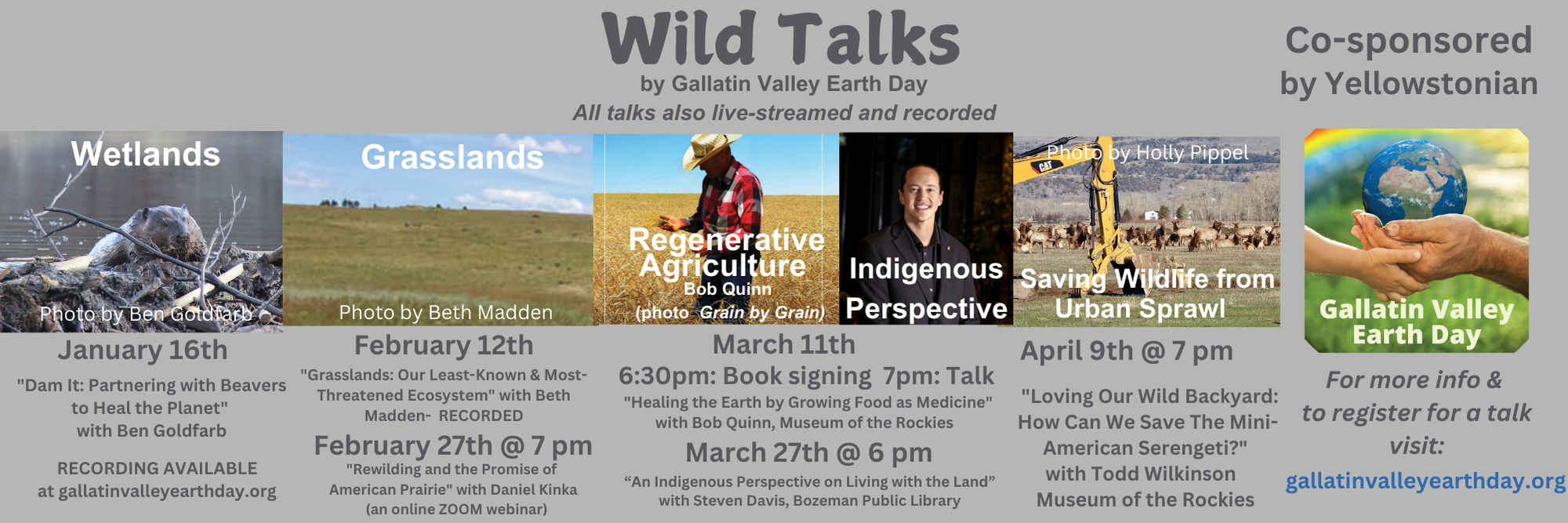

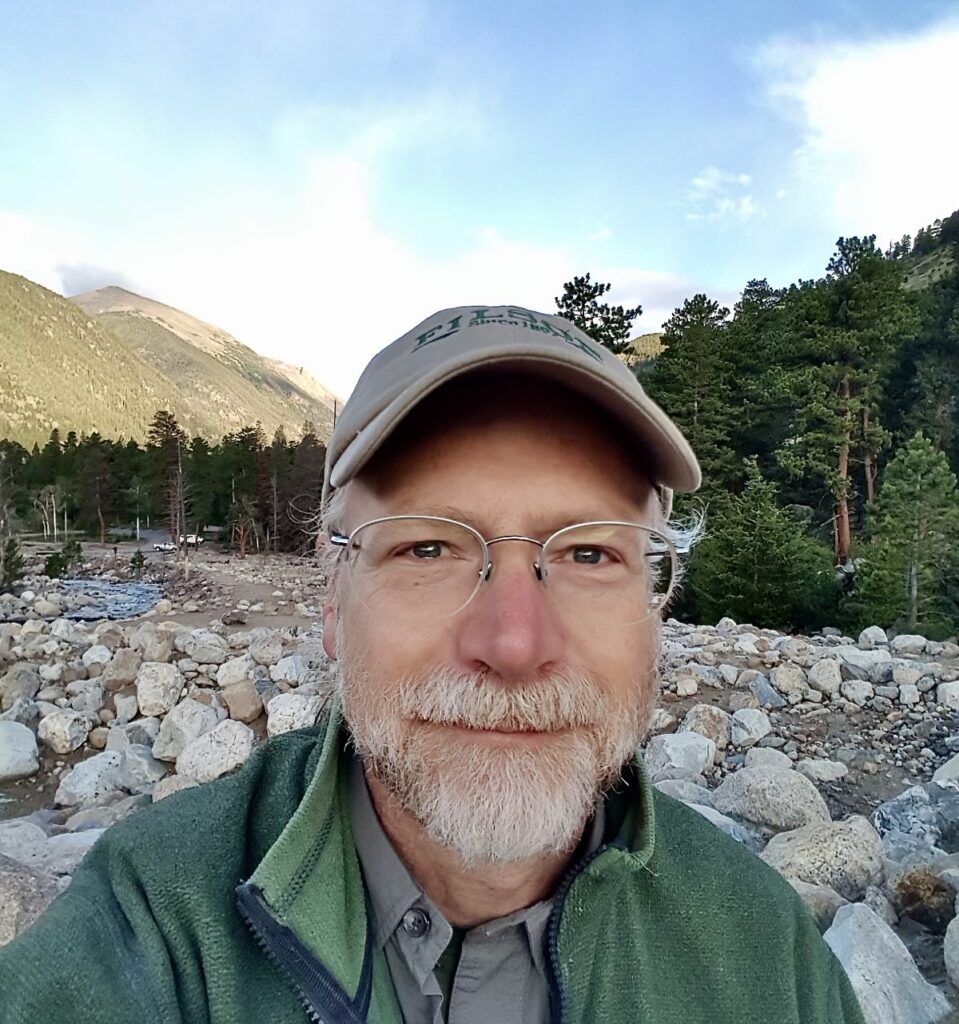

One of the authors and editors of the new Stegner critique, Fiege, holds the Wallace Stegner Chair in Western American Studies at Montana State University in Bozeman. He is widely regarded as a leading thinker about “the New West.” The Yellowstonian recently engaged him in a wide-ranging chat about the book, Stegner, threats to the integrity of nature, and the current state of the conservation movement. Wallace Stegner’s Unsettled Country is published by the University of Nebraska Press an is available wherever great books are sold. We suggest supporting your community by picking up a copy from your local independent bookseller.

TODD WILKINSON: In some ways, in recent years and especially in these socially-turbulent times when contemporary historical criticism in academia often offers a harsh reinterpretation of people in the past, why does a fresh examination of a writer and thinker like Wallace Stegner matter? Particularly for those of us who dwell in a West that Stegner viewed as home ground and who explored it in both fiction and non-fiction?

MARK FIEGE: Stegner still matters in multiple ways. Anyone who wants to understand the West and places like Yellowstone must come to grips with its history, and Stegner has a prominent place in that history. He both wrote about Western history and was a player in it. Someone today might not like Stegner, but he mattered back then and he matters now. He was one of the leading western American intellectuals and writers of his time. He produced numerous works of fiction, history, and essays that expressed the beauty, folly, and promise of the region. How he defined the West and its problems influenced many people, then and since, including prominent western intellectuals and writers, including the historians Patty Limerick and Donald Worster, the law professor Charles Wilkinson, and the memoirist and essayist Terry Tempest Williams.

TW: That by itself is an influential quartet of conservation-minded thinkers.

FIEGE: Yes, and Stegner himself was an influential conservationist who spoke out on behalf of national parks and wilderness. He called himself a reluctant conservationist because he really wanted to be known as a novelist. Yet he used his remarkable ability with language to sketch a compelling picture of an alternative way of life in the West that accepted the region’s environmental limitations while appreciating the immense cultural potential he saw in its vast open spaces. The problems Stegner explored, such as the human cost of life in a resource extractive economy, are still with us, and his solutions to those problems—the need for living small in community with other people and with the land—remain relevant. Anyone who wants to understand the West and find a way forward in it might begin by reading Stegner’s short book The American West as Living Space followed by an equally brief but powerful work by his protege and friend Terry Tempest Williams, The Open Space of Democracy.

TW: In your lead essay, you make clear that the book is not a hagiography when you write, “Wallace Stegner was hardly a perfect person or writer, especially by today’s standards. There is good reason why feminists, Native people, and other writers and intellectuals find his work objectionable. For such a humane, liberal-minded man, he sometimes wrote things that have made readers cringe, then and since.” And that “…always at the center of his stories, always at the center of his imagined western American experience—as if there is such a singular thing—was a white man much like himself.”

FIEGE: Those are facts of who he was. By emphasizing this at the very beginning, this then opens the door to embark upon a fuller and broader discussion about how we think about the West that figured at the center of his thinking.

TW: Among the many things I enjoy about your book and the essays from differing authors is how they get at something that is elusive. It was for Stegner, too, and I would assert that it exists for many. It involves a question that rises out of the gut and heart: what does it mean to have a connection to the land? Whether one has an ancestry in the West that goes back 200 generations, six or you’re a recent arrival from a city, what is it that brings a meaningful existential connection—not a mere in-the-moment visceral one— as in really coming to know a place or a landscape? To speak of it intimately, lovingly and with respect?

FIEGE: That is a great question and most of our authors wrestled with it. Stegner wrote about the West’s beauty and its openness, but knowing a place involves—requires, I would say—so much more than just witnessing its beauty and enjoying it recreationally. Recreation takes many different forms, and not all of them are conducive to deeper reflection on what it means to be in place if the only intent is using it or taking from it. To know the West, to know a place or a landscape in it, more than anything requires you to experience struggle and defeat in that place, to have your body and heart broken in that place, to have your dreams smashed and your soul crushed there. This isn’t the same thing as going out on an overnight hike, taking a long ride on a mountain bike, or peak bagging. It involves having the place you think you love slap you down, wreck you, and nearly destroy you. When you have suffered enough and realize that you are beaten, only then are you prepared to understand the redemptive power of the West’s beauty and openness. Parts of you must die for you to shed your illusions and achieve resurrection and transcendence in better relation to other human beings and the land.

“Stegner wrote about the West’s beauty and its openness, but knowing a place involves—requires, I would say—so much more than just witnessing its beauty and enjoying it recreationally. Recreation takes many different forms, and not all of them are conducive to deeper reflection on what it means to be in place if the only intent is using it or taking from it.”

—Mark Fiege

TW: Stegner clearly sought to debunk the myth of limitless resources out there that can be limitlessly consumed without huge negative consequences. Many say the 21st-century outdoor recreation industry and its relentless push to open more access to public lands so that it can expand the market of people buying stuff exists in parallel to the kind resource extraction thinking which Stegner condemned. What you just said will likely “trigger” some self-obsessed recreationists who are unable or unwilling to understand what you’re saying. It sounds like what you’re getting at involves something bigger than testing one’s ego, physical prowess, or movement powered by human muscles or engines.

FIEGE: This is something I try to get my affluent students, obsessed with consumer goods and recreation, to understand. The key to knowing a place or landscape is not through fun; it is through struggle, sacrifice, destruction, loss, pain, and, ultimately, when you feel defeated, demonstrating empathy and compassion for people and other living things. Your pain and sorrow will enable you to know what true recreation is—the re-creation of the heart, mind, soul, and self without egotistical illusions—and to truly appreciate the redemptive power of the West’s unspeakable beauty.

One of our contributors, Alexandra Hernandez, a National Park Service professional with deep family roots in the West, wrote a brilliant essay—”The American West as Exploited Space”—the opening of which makes me emotional every time I read it. Alex meant her essay to be a critique of Stegner, and it is, and powerfully so. Yet that opening story, which always brings tears to my eyes, is so very, very reminiscent of Stegner. The key to truly knowing the West and places like Yellowstone is not fun-filled mass-consumer recreation; it is struggle, ruin, and sorrow and the wisdom that comes from having to put the pieces of your broken life back together so that you can try again to find your way to a humane, just, life-affirming existence.

TW: We’ve spoken about this, but you believe that empathy and compassion as virtues should be extended not only to people and to place, but also toward the non-humans who are authentic, original expressions of place and who, across much of the West, have taken a beating by human ambitions to profit from or conquer the landscape. This, too, was also one of Stegner’s threads.

FIEGE: What you are saying makes me think of Pope Francis and Laudato Si: On the Care of Our Common Home, his encyclical on climate change in the tradition of St. Francis of Assisi. Pope Francis decries the egotistical excesses, callousness, and waste of mass consumer society, and he observes that anywhere we find the mistreatment of people, we also will find the mistreatment of animals–and vice versa. Think of the millions of recreators speeding down the highways of Montana, Wyoming, or Idaho hell-bent on getting to Yellowstone in callous disregard not only for the lives of their fellow humans but also for the wildlife that they and their vehicles slaughter. Such behavior is a brutal violation of the beauty and wonder of the Creation and the sanctity of life.

The flip-side of the callousness, of course, is that anywhere people have compassion for animals, they also generally have compassion for other human beings, and Stegner himself recognized as much. In one passage I can recall—in the essay “The Rediscovery of America: 1946”—he reflected ruefully on the roadkill that covered the highways of the West. In his famous “Wilderness Letter,” he said he learned as a child that the Earth is full of animals and that he must recognize them as his little brothers, as fellow creatures. This is similar to the way indigenous oral traditions teach reverence for animals. I have no doubt that if Stegner were alive today, he would express deep concern not only for the human cost of today’s recreational gold rush, but also for the lives and unremembered deaths of millions of wild creatures lost to the self-absorbed egotism of that frenzy.

In his famous “Wilderness Letter,” Stegner said he learned as a child that the Earth is full of animals and that he must recognize them as his little brothers, as fellow creatures. This is similar to the way indigenous oral traditions teach reverence for animals. I have no doubt that if Stegner were alive today, he would express deep concern not only for the human cost of today’s recreational gold rush, but also for the lives and unremembered deaths of millions of wild creatures lost to the self-absorbed egotism of that frenzy.

TW: For those who are unfamiliar, what kind of connection did Stegner have to Montana State University and Bozeman? He taught at Stanford and wrote from Palo Alto and had early connections to Salt Lake and even Great Falls, Montana after his family left Saskatchewan. The link he had to MSU, which is also the only major university located geographically inside the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and where you have been the Wallace Stegner Chair, is poignant.

FIEGE: Not many people know about that, but it is important and integral to the larger story of Stegner’s relationship to Montana, a story that no one has told in full. In 1987, Montana State University awarded Stegner an honorary doctorate. Stegner was deeply appreciative and sincerely thanked the university for recognizing him in a manner that eastern universities and institutions and eastern literary arbiters never did and never would. He praised MSU and Bozeman for epitomizing the kind of small-community virtues that he prized. The warmth was reciprocated, and numerous people in the MSU community—faculty, students, staff—wrote to Stegner in heartfelt admiration and gratitude. Two contributors to Wallace Stegner’s Unsettled Country, Nancy Cook and Melody Graulich, wrote insightful essays on Stegner, education, and students, and this side of Stegner is strongly evident at MSU.

TW: Indeed, he passed through Bozeman every so often and was an advocate for a bill in Congress that would have given Montana its first statewide wilderness legislation but it got vetoed by Ronald Reagan literally as he was ending his second term as president in 1988.

FIEGE: Stegner returned to the university in 1992 to read from his recently published collection of short stories, and MSU recognizes that moment as the foundational Wallace Stegner Lecture, now an annual event. Stegner’s connection to MSU motivated members of the MSU community, notably philosophy professor Corky Brittan and his friend Susan Heyneman, both of whom were close to Stegner, to begin building an endowment for a Wallace Stegner Chair in Western American Studies and for the annual Stegner Lecture. That’s the position that I and others who came before me have held. Stegner died in 1993, from injuries suffered in a tragic car wreck in Santa Fe, but by then he knew that MSU was going to establish the chair in his name, and his wife, Mary, contributed $25,000 to the endowment, a sizeable chunk now and an even more sizeable chunk back then.

TW: It was a big deal, for those who don’t remember it, and it brought to town a thinker I greatly admired, T.H. “Tom” Watkins, who had served as editor in chief of Wilderness magazine, a publication that was published by The Wilderness Society and subsequently was discontinued. Wilderness magazine, and its predecessor, The Living Wilderness magazine, gave voice to the multi-dimensional importance of wildlands that arguably is absent from the mainstream conservation movement.

FIEGE: Yes, Tom Watkins left Washington DC and was the first person to hold the Stegner Chair. He was Stegner’s dear friend and protege and a prominent conservationist, wilderness advocate, magazine writer, and prize-winning biographer of Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior in the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. He had been in the chair for about two years and was working on a biography of Stegner when he was diagnosed with cancer and died suddenly. His passing was a tremendous loss for MSU, Montana, Yellowstone, and conservation, and sadly, his time at MSU and his contributions to the university often are forgotten.

There are many sides to the Stegner legacy at MSU and it is impossible to convey them in full in this space but suffice to say that they are rich and very special to the institution. They lend credence to the argument you and I make that Greater Yellowstone ought to be the epicenter in the US for thinking about relationships to wild and undeveloped places that are rapidly dwindling. Stegner is known for his ties to the universities of Utah and Iowa, where he earned his degrees, and Stanford, where he built a renowned graduate creative writing program.

TW: Few people realize that Stegner influenced acclaimed Greater Yellowstone-based writers like Tom McGuane and the late William Hjortsberg, both of whom were Wallace Stegner Fellows in the creative writing program at Stanford that Stegner founded. Besides his novels, McGuane remains a contributor to The New Yorker magazine and his short stories published there are sweet, but not always, reflections of people in rural interior of the West. McGuane talks about his characters in an interview published in The New Yorker in spring 2024. But, back to MSU.

FIEGE: MSU has one of only two endowed Stegner chairs in the country. The other is at the University of Utah Law School and currently held by Bob Keiter, who contributed a wonderful essay to our book on the Stegner legacy and the creation of Bears Ears National Monument.

TW: Bob Keiter is a true big picture thinker and author of the forthcoming The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Revisited, which ought to be approached as a must-read for anyone who cares about this place—especially the hundreds of young people who today work as staffers at national, regional and local conservation groups based here.

FIEGE: I agree. I think that’s important and there’s a long list of other writings that speak to how the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the place and the concept, came into being.

TW: In the 1980s, Stegner served on the governing council of The Wilderness Society along with other influential conservation leaders. What was Stegner’s Wilderness Letter and why is it a touchstone for you?

FIEGE: The Wilderness Letter is one of Stegner’s most powerful and enduring essays. It dates to 1960 and is best known through its republication in his book The Sound of Mountain Water. Various of our contributors address the Wilderness Letter, but notably, and most thoroughly and thoughtfully, the historians Leisl Carr Childers and Adam Sowards in “Hope in Public Lands.” Stegner’s reflection is most famous for its final sentence, which refers to wilderness as “part of the geography of hope.” A sense of wilderness as an antidote to the mechanization, relentless reductive instrumentalism, mental illness, and spiritual impoverishment characteristic of modern society pervades the essay, as does the sense of wilderness as a home to myriad creatures with whom human beings have kinship. More importantly, I believe, the essay conveys a living, breathing, heartfelt sense of wilderness as an expansive, capacious space with infinite potential to inspire and energize human faith, imagination, and creativity.

TW: Your own thinking continues to evolve. You and your wife, Janet Ore, live close to public lands in a small town where she spent her high school years and it sits astride private lands very vulnerable to subdivision which, in turn, would impair the wildlife values that flow off of and into public lands. Why is Stegner’s Wilderness Letter something that’s included as a necessary read for students in the classes you teach?

FIEGE: Stegner’s Wilderness Letter is significant to me personally because it reminds me that the public lands—places such as Yellowstone National Park and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—never have had a single static purpose, use, or meaning. Rather, the range of purposes, uses, and meanings that people discover in those places is breathtakingly large, expansive, inclusive, and virtually infinite. Places such as Yellowstone have the potential to bring people together based on universal values that we share. They have the potential for people like me to reckon with and rectify the destruction and dispossession that the United States meted out against Native tribes. As long as those landscapes remain open and free of machinery and development as Stegner desired them to be, as long as they can sustain animals and other living things, they have the immense potential to help revitalize and redeem the American republic.

TW: The intense human development pressure that existed in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia came relatively late to North America. While some Indigenous peoples had become farmers because it was the most efficient and reliable way to sustain populations, they were not industrialized, at least in ways that the return of the horse and the introduction of firearms altered how people related to each other and to the land. So what is the through-line that you see with the shared natural heritage of North American that transcends Indigenous peoples and the arrival of Europeans?

FIEGE: Undeveloped, un-mechanized landscapes hold out the possibility that the republic still has the power to fulfill the humanitarian and moral potential—the revolutionary potential—that the Founders of the United States envisioned for us. I believe Stegner understood this and tried to convey it in an essay that everyone in the United States should read at moments when they wonder if the future is worth struggling to secure. It gets at both the ecological virtue of modern conservation and the innate belief systems and reverence for nature that has existed among virtually all peoples.

Undeveloped, un-mechanized landscapes hold out the possibility that the republic still has the power to fulfill the humanitarian and moral potential—the revolutionary potential—that the Founders of the United States envisioned for us. I believe Stegner understood this and tried to convey it in an essay that everyone in the United States should read at moments when they wonder if the future is worth struggling to secure.

TW: A personal confession: I sometimes struggle with a sense of melancholia that comes over me when I read Stegner’s fiction. Yes, there’s passages of humility, awe and wonder, yet it’s almost as if there’s a strain of depression, muted hope or shades of loss that runs through some of the characters, too. Where does that come from? Does it persist among real people in the isolated West? And is it curable?

FIEGE: More than anything else, Stegner knew first-hand the nature of failed dreams, brokenness, ruin, loss, and sadness, and his characters consistently convey those feelings and their struggles to overcome them. The myth of the American West is sunny—it’s a place of blue skies, starting over, wealth, security, self-fulfillment, and contentment. But Stegner knew the underside of that happy dream. He knew that the West also is a place of failure, ruin, and sorrow. The historian Patty Limerick, who has spent a fair amount of time pondering the West’s “legacy of conquest” and “the burdens of western American history,” pointed out that Stegner often looked sad and that few published photographs show him smiling. He was a man who knew loss and the feeling of never really fitting in anywhere.

TW: That’s a common feeling for many people, especially rural people who feel isolated physically and emotionally. How does one deal with it within the context of the West?

FIEGE: The antidote to depression, shattered dreams, and sadness, in Stegner’s estimation, was—and is—to reckon with the past’s painful lessons and, in that sorrowful awareness, to try again, to start over but this time clear eyed and without illusions. In that moment, the beaten will truly appreciate the crystalline clarity of dry Western air and expansive Western vistas and will feel a deep yearning to find a small humble space of solace and redemption under the eternal sunset and distance—often with sun rays breaking through patches of cloud—that in Montana we call the Big Sky.

TW: Quick clarification: You are not referencing Big Sky the high-end resort enclave, but rather to A.B. Gurthrie’s notion of it as a place to which we aspire to belong with humility and shared respect for its beauties, wonders, and potentials.

FIEGE: No, I am not referring to Big Sky, the human creation which is an exploitative contradiction to the conservation values of Montana, the West, and the likes of Guthrie and Stegner.

TW: So, please elaborate on what Stegner’s vision was, especially in the wake of Manifest Destiny and the often harsh treatment of the West as a natural resource colony for exploiters in distant cities. Be it William Jacob Astor, the New Yorker whose fur company contributed to the near extinction of beaver, or be it the Copper Kings who extracted vast wealth from Montana but who spent much of their time and riches elsewhere.

FIEGE: The environmental and human ruin that Stegner experienced and witnessed and about he wrote so movingly still is with us. Stegner recognized the damage wrought by resource extractive capitalism and mythologies of individualism and dominance over nature. His favorite symbol of destruction was the bulldozer. He has been gone for over three decades now, but we still live in his time, and many of his ideas and words remain true and powerful for us today. Stegner was at his best, his most perceptive, when he wrote about the struggles of ordinary people and families who were the casualties of the relentless drive to wring wealth from the land.

The problems that he saw and knew all too well—isolation, alienation, estrangement, poverty, loneliness, confusion, violence—now are reaching epidemic proportions and afflict the West more than ever. Two of his best novels, The Big Rock Candy Mountain and its sequel, Recapitulation, are testaments to those profound problems. Yet Stegner had a cure: appraise the past honestly, find a place to live and stay there—stick, and reach out to others to build community as you strive to achieve a decent, reasonable relation to the land and its limitations.

TW: Stegner is among a series of white males who played important roles in advancing conservation. Some of them have landed on various cancel-culture lists compiled by people who seem motivated not just to scrutinize their status as humans but to delegitimize them and then extrapolate further as an attempt to delegitimize conservation in general.

The list also includes John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt, Aldo Leopold, Edward Abbey and even recent takedown attempts in Jackson Hole aimed at Olaus Murie. One counter-argument is that they were products of their time and while not peerless or without fault, they spoke out for land and species protection when it was unpopular to do. As an environmental historian, how do you see them?

FIEGE: No one is perfect, and that includes many of the white male icons of classic conservation history. If Stegner were alive today, and if we could talk with him and hold him accountable to his insistence that we be honest about the past, I believe he would have to acknowledge the racism and sexism of a substantial number of conservation’s founders and proponents. I would like to think, however, that Stegner would not agree that the answer is cancellation—to not read the words of white male conservationists, to pretend that they did not matter to the world that we have inherited, to dismiss them as objects of study from whom we can learn—is to make a virtue of denialism, censorship, and ignorance. You don’t have to like the conservationists in every regard if at all, but you are a fool if you refuse to take them seriously, read them, learn about them—and learn from them. The same with Stegner.

TW: Lacking among some cancel culturalists is a coherent and honest articulation of what the alternative would have been. Yellowstone is held up by some as a symbol of ignominy. And it’s true that the Tukudika, the Shoshone people known as the Sheepeaters, most notably, were prevented from continuing to live seasonally and engage in subsistence activities after Yellowstone was created. But Yellowstone is only a tiny reference point in a continent-wide phenomenon of removal, genocide, and injustice. The larger value of Yellowstone, ironically, is that it was a bold pushback against Manifest Destiny, that the total sublimation of nature would not continue there and that it supported the idea that some natural places ought to be set aside as inviolate. That’s a concept that many tribes practiced with regard to certain places, in reverence for wildlife and the power they possessed as Native peoples expressed in traditional ceremonies.

FIEGE: In the case of Stegner, you don’t have to like the man and the writer, and it’s understandable why some people object to him. But willful ignorance is not a virtue. The flip side of cancellation, of course, is idol worship or hagiography—the great man could do no wrong—but that, too, is a form of willful ignorance and a refusal to confront difficult and troubling historical realities. We need to see the early conservationists, and Stegner, in the fullness of their lives, much as we would like people in the future to see us in the fullness of ours. Are we perfect? Are you perfect? “To hold Stegner exempt from criticism,” the critic A.O. Scott wrote a few years ago, “seems to me as shortsighted as refusing to read him.” The same goes for conservationists. They were not perfect, but they shaped the world we inherited. Not all were racist and sexist, and not everything they advocated or did was totally wrong, useless, or meaningless. The judicious study of the past summons us to be responsible citizens, not ignorant censors and cancel culture nihilists. The historian Richard White, in an underappreciated essay, referred to “the problem of purity.” It is ironic, and a pity, that the cancel culture liberal left and the denialist conservative right, in their zeal for purity, both dislike and reject the conservationists. Both groups have much more in common than they know.

The judicious study of the past summons us to be responsible citizens, not ignorant censors and cancel culture nihilists. The historian Richard White, in an underappreciated essay, referred to “the problem of purity.” It is ironic, and a pity, that the cancel culture liberal left and the denialist conservative right, in their zeal for purity, both dislike and reject the conservationists. Both groups have much more in common than they know.

TW: This is exactly the kind of nuanced conversation about the merits of ecologically-minded conservation that has been lacking, ignored or silenced in recent years. In the West, there is a huge level of rumbling going on related to the perception of how wildlife conservation organizations have lost their way.

FIEGE: If we take conservation and its proponents seriously, we also will discover considerable variation and diversity in their thought and practice. Sooner or later, diligent students of conservation history will encounter the life and work of Galen Clark, a frontiersman—a “settler colonial” or “settler colonist” in today’s parlance—who believed that the problem with Yosemite National Park was that it needed Native people to come back and burn the land and tend the oak trees so that vegetation would not overtake the Tuolumne Valley. They will discover Col. John Roberts White, a vicious, violent racist during his early days in the Philippines but who later, as superintendent of Sequoia National Park, renounced colonialism and racism—and cruelty to wildlife, which he likened to the torture of human beings—and defended the Japanese Americans during their wartime incarceration. They will come across Floyd and Ruth Schmoe, Quakers who worked at Mount Rainier National Park who looked the other way when Yakama people came into the park to pick blueberries and who believed that national parks could serve as sites of reconciliation and the healing of trauma in the aftermath of global conflicts.

TW: As you well know, the very same organizations who are not familiar with those examples are retreating from their former positions of seeking wilderness protection because they knew it was the best way to safeguard habitat for wildlife but who now instead make convoluted arguments that having more recreational access both equates to better wildlife conservation outcomes and somehow resolves issues of racism. But there is proof for neither.

FIEGE: If people who are retreating from touting the value of wilderness protection would dig a little deeper, they will find Robert “Bob” Marshall, namesake of one of Montana’s great wilderness areas, to have been a person who, more than any other early conservationist, recognized the significance of class, race, and gender to conservation. He listened to and heard the laments and cries of women, including Native women, and who envisioned a democratic conservation that addressed the needs of working class Americans and the rights of Native people. And if diligent students persisted in their research, they might stumble upon the great Black historian W.E.B. Du Bois and his book Darkwater and its deeply meaningful and richly metaphorical description of his visit to the Grand Canyon.

Question: What would modern conservation and protected landscapes look like today if people like Stegner and others had not existed in their day?

Fiege: For all its faults, and it had them, conservation gave us a world far richer in beauty and possibilities than if people back then had canceled and defeated it. Stegner was right to speak out on behalf of conservation, and he left us a gift in his Wilderness Letter.

TW: When I was writing my book about Ted Turner, I interviewed Bernice King, daughter of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who said if her father had survived he would have seen environmentalism as a necessary component of the civil rights movement and he would have been a champion of extending respect for the survival of non-human beings.

FIEGE: Bernice King’s observation of her father reminds me of Pope Francis and his assertion that the fates of people and animals are conjoined, and that people and animals are partners in their great journey back to God. I could go on with examples of how the cause of conservation, especially wildlife conservation, is not the monolith that some have portrayed it to be. I hope you see my point. Rather than canceling white male conservationists, dismissing conservation, and making a virtue of ignorance, it is far better for all of us to explore the rich and amazing conservation tradition and its vast potential for protecting and caring for people and nature alike. We might revisit one of Aldo Leopold’s most famous and moving essays, “Thinking Like a Mountain,” and recognize that Leopold was inching toward a mystical resacralization of nature in which people are part of a larger ecological community, that his idea broke from colonial patterns of thought, and that it harkened to beliefs that Native people had held for millennia. We ought to see conservation as a vast field of possibility and source of ideas and inspiration as we struggle together to create the better, more just and fairer world that all of us in our hearts know is possible.

Conservation is like the public lands—it can’t be reduced to a single static definition or meaning. Its potential is capacious and virtually infinite. The future will be better if we create it from the conservation tradition. It will be poor and bleak and dead to the extent that we ignore, censor, or cancel conservation and its immense potential. I believe Wallace Stegner would agree and would urge us to come together in our humanity and our shared love of nature and, in the spirit of the best that conservation offers, rescue the world and ourselves with it.

TW: This is not a question intended to provide deflection from any justifiable critiques. But what would modern conservation and protected landscapes look like today if people like Stegner and others had not existed in their day?

FIEGE: Imagine this: the Grand Canyon dammed and turned into a giant reservoir; buffalo herds, eagles and other raptors, and legions of many more kinds of wild animals—wolves, grizzlies, mountain lions and more—extirpated or extinct and existing only as sad memories; Glacier National Park and the Badger-Two Medicine privatized and exploited for gas and other resources, forever and irredeemably depriving the Blackfeet Nation and its people from the places they need to restore and conserve their culture and heal their trauma; the east side of Grand Teton National Park a garish nightmare of neon and casinos, cheapening the magnificent silhouette of an iconic mountain range; Redwood and Sequoia forests wiped out for lumber, most of which rotted or burned or wound up in landfills in the nation’s zeal for the quick easy dollar; Yellowstone Lake dammed for irrigation in Idaho and Montana; Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument dammed, inundating a rich cultural landscape and one of the quietest spots in North America if not the world; salmon fisheries obliterated; and the list goes on—without conservation, the catastrophic loss of undeveloped lands, including cultural homelands, and the organisms they contained would have been much, much worse than it has been.

Or think of the United States without public lands. The United States, the West especially, would look a lot more like Texas or the United Kingdom, where the public has legal access to only a fraction of land. In places like Texas or the UK, to roam across the terrain and fully exercise your humanity, you must break the law and engage in trespass. Is that the kind of world anyone would choose? For all its faults, and it had them, conservation gave us a world far richer in beauty and possibilities than if people back then had canceled and defeated it. Stegner was right to speak out on behalf of conservation, and he left us a gift in his Wilderness Letter. Open, unruinded land is a treasure, and all of us need to come together to protect it and save it for all the right reasons.

FINAL NOTE: Listen by clicking here to Robin Young of public radio’s Here and Now discuss Stegner with Melody Graulich who wrote one of the essays in Wallace Stegner’s Unsettled Country. Also read: Stegner’s “Wilderness Letter” Still Rings True.