by Todd Wilkinson

To their piqued ears, the first distant notes of what would inspire a lobo rhapsody sounded wistful, almost forlorn. A cappella, they floated toward Dan Stahler, Kira Cassidy and Jeff Reed. Traveling invisibly through the capacious space of America’s first national park, they filled the high mountain air of Yellowstone’s Northern Range with what seemed like a plaintive plea for companionship.

Maybe a quarter minute’s worth of dead quiet ensued. And then, emanating from topography in a different direction well out of sight, that singular call of the wild was answered.

The reply began with one crooner, soon joined by two more. Eventually, with upwards of a dozen members of the Rescue Creek Pack taking part, the “chorus howl” of wolves seemed as harmonically dulcet and uplifting as The Beach Boys singing “I Get Around” in their call-and-response classic.

For the three seasoned human listeners, there were no decipherable “words” detected—at least not yet—but the primordial wall of sound still gave them a chill, not of fear but gratitude. This is among the many delights that come with being part of the most extensive ongoing research effort in the world focused on the behavior of wild gray wolves.

Howling is one of the most universally recognizable wild animal sounds on Earth, distinct among trumpeting elephants, bugling elk, trilling loons, whistling dolphins, roaring African lions and Indian tigers, cawing corvids, singing whales, and, of course, the abundant larger avian banter that you can likely hear now as you’re reading this.

And yet, still…

“Nothing symbolizes a wolf, and translates what it is, as a social animal, more than its howl,” Stahler says. “I’ve known few people who aren’t genuinely moved whenever they hear a pack howling. It’s a sound you never forget—one that’s been present in the memory of our species for a long time.”

“Nothing symbolizes a wolf, and translates what it is, as a social animal, more than its howl. I’ve known few people who aren’t genuinely moved whenever they hear a pack howling. It’s a sound you never forget—one that’s been present in the memory of our species for a long time.”

—Dr. Dan Stahler, senior wolf biologist in Yellowstone National Park

As soon as the unexpected serenade halted, Dr. Stahler, Yellowstone’s chief of wolf research; Cassidy, an experienced independent field biologist who is funded through Yellowstone Forever; and Dr. Reed, a high-tech maven from Paradise Valley, Montana, fastened the last of their remote audio recorders to trees and then hiked out of the backcountry before dark.

Those tiny devices—listening posts now generating many terabytes of sonic data—are helping to radically transform human understanding of the language of wolves. An array of 10 recorders is positioned throughout Yellowstone’s Northern Range within known wolf pack territories, plus 23 radio collars on animals in seven packs, 13 of those being GPS enabled delivering location fixes every hour. A separate and related monitoring effort is underway with the public Beartrap Pack that has long resided on Ted Turner’s Flying D Ranch southwest of Bozeman.

Revelations are coming fast and they’re opening a new window into the lives of these highly sociable carnivores that never existed before. It’s yet another dividend of reintroduction.

° ° ° °

The eminent Minnesota-based wolf biologist L. David Mech, whom I’ve known for nearly 35 years, has spent his life studying Canis lupus. Dr. Mech has a new book coming out soon related to his work on Ellesmere Island in northern Canada. Generally, Mech says, wolves use vocalizations like ship captains do. In a nautical setting, sonar pulses are sent through the water to sound off the bottom of oceans to discern what’s out there. Wolves, by howling, do something similar terrestrially; howling—and eliciting replies—is their way of connecting with other pack members, sending warnings to interlopers, and even conducting an informal census.

At an international conference held in April 2024 at the Sante Fe Institute in New Mexico, experts involved with bioacoustics, a rapidly expanding field, gathered to share notes on cutting-edge research into decoding the language of other animal beings on the planet. Reed was prestigiously invited to make a presentation. From whales, dolphins and birds to amphibians, elephants and wolves, some stunning discoveries are being made about animal communication, he says.

The work being done in Yellowstone, though still in its early days, was a topic of keen interest in Santa Fe. Several high-profile venture capital businesspeople, who have a soft spot in their hearts for wildlife conservation, were present and intrigued. Artificial intelligence and generative machine learning, Reed says, now enables huge volumes of data to be processed. In the case of Yellowstone, tens of thousands of hours of recordings of wolf communication.

“The main advantage for bioacoustics tech is that it allows us to listen all of the time, which is not feasible with human researchers and it can quickly become too expensive,” Reed says.

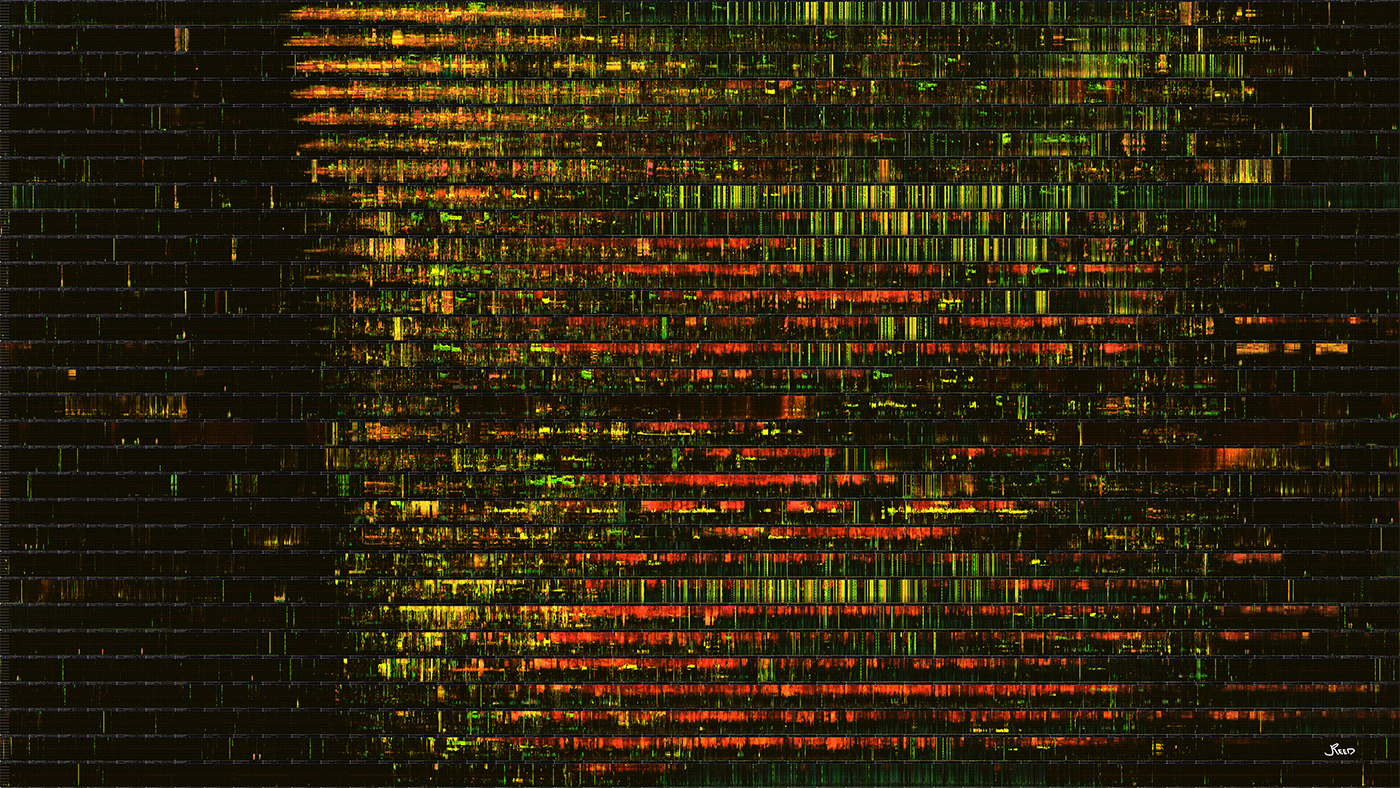

In a nutshell, the technology identifies patterns in vocalizations on algorithms that analyze the audio in a visual form, called spectrograms. A spectrogram is simply a visual representation of what your ear is hearing. Stahler, Cassidy, Reed and colleagues are cross-referencing recordings made by individual wolves and the packs to which they belong with associated observable group behavior. From that they are trying to extrapolate insights, for example what might it mean when certain kinds of chorus howls erupt during breeding season or winter hunting season?

The biggest breakthrough will be if bioacoustical overlays can be applied to the mountain of data that has been assiduously collected going back the very genesis of wolf reintroduction that happened in 1995.

Reed, who lives near Emigrant and was born and raised in Montana, got his undergraduate degree in anthropology and linguistics at a small college in California. He eventually earned a PhD. Linguistics is the study of languages—how they originated, evolved, and how words organized in sequences reflect a lot about cultures, societies and the capacity of our species to think. “I’ve always had a fascination with human linguistics and only in recent years have I been thinking about how some of the same kind of analysis might be applied to other species,” Reed says.

There was a time when Reed thought of becoming a professor and teaching linguistics but other opportunities and necessities intervened in his life, including the essential one of how to make a living. It has been Reed’s other talent, software programming which dates back to his teenage years in the early 1980s, that has become his primary professional income generator.

A self-described “analytical nerd,” he has been contracted by many large tech firms in Silicon Valley to write and test hardware and software programs. Being able to base himself anywhere, he returned permanently to his native state a few years ago and has been lending his skills to a number of different wildlife conservation efforts in the northern tier of Greater Yellowstone.

“Both of my interests really converge with wolves,” he said. “Here we have one of the most highly sociable and communicative animal species on Earth—wolves—and just down the road we have in Yellowstone the world’s most famous wolf population. Rapid advancement is making it possible to try to truly hear what they are saying.”

“Here we have one of the most highly sociable and communicative animal species on Earth—wolves—and just down the road we have in Yellowstone the world’s most famous wolf population. Rapid advancement is making it possible to try to truly hear what they are saying.”

—Dr. Jeff Reed of the Cry Wolf Project

On the day I visited Reed at his home, we gathered in a large room. Immediately outside a picture window was the Yellowstone River and backdropping it the loom of Emigrant Peak, among a line of mountain summits in the Absaroka Range that runs southward from Livingston into the northern reaches of Yellowstone.

My attention was quickly attracted to melding lines of color appearing on a large screen TV. With a spectrogram, one could easily mistake the image for a modern, abstract expressionistic painting. Reed’s TV is positioned on a wall above the fireplace between two mounted deer bucks that he hunted a few years’ back.

After he pressed a button on a hand-held clicker, magic happened. Colors on the screen began to move, vibrating, spiking and glowing. You might think of a medical EKG machine meeting the soundboard of a professional music recording engineer, who is tweaking volume levels so that color bands representing sound rise and fall.

The setup allows for wolf howls, which otherwise only exist in the ether and invisibly, to assume physical visual substance, including appearing as a range of frequencies that would be beyond our hearing capabilities.

As I closed my eyes and Reed gently turned up the volume, the room flooded— akin to lobo monks singing Gregorian chants in a Medieval monastery—with a succession of chorus-howl recordings of Yellowstone wolf packs, punctuated occasionally by growls, barks and whines. Reed had at his disposal nearly 1,200 chorus howl events.

Echoing in surround-sound, it was the quintessence of a total call of the wild immersion, albeit a virtual one far from where the recordings were actually made. “You need speakers with good woofers to convey the nuances of each wolf vocalization,” Reed said with a straight face, not betraying the obvious humorous intent of its wry delivery.

As I closed my eyes and Reed gently turned up the volume, the room flooded— akin to lobo monks singing Gregorian chants in a Medieval monastery—with a succession of chorus-howl recordings of Yellowstone wolf packs, punctuated occasionally by growls, barks and whines. Reed had at his disposal nearly 1,200 chorus howl events.

Any human who spends time around domestic dogs knows that, as individuals and in small groups, these beloved canids don’t often howl but they do bark and growl. And they project their own body language often reflecting their attitude in the moment. Owed to their time co-evolving in our company, barking and growing is their way of expressing alertness to the approach of intruders they can hear or smell. Whining is their way of telling us they feel left out. Hearing and smelling things, then responding with an associated vocal response, is one of the high-graded sensing capabilities that are part of domestic dog behavior that resulted from living with humans in close-quarter settings.

For wild wolves, whose territories encompass big living spaces, their primary means of communicating across territories is through howling. It’s how they navigate at scale. Reed says humans measure sound through audio frequencies. They reach our ears as detectable vibrations and then are processed in our brains. The main unit of frequency measurement is a Herz (Hz) and one of the properties of sound is pitch. For most humans, Reed says, the range of hearing falls between 20 and 20,000 Hz and we are most sensitive to frequencies between 2000 and 5000 Hz. “We speak in frequencies between 85 and 255 Hz,” he says. “Wolves howl on average at 350 Hz.”

Howling has an existential function. Wolf chorus howls can carry across long distances due to their low frequency and the force at which they are emitted. The average wolf howl, Reed explains, is the equivalent of you standing 10 feet in front of your car and then experiencing the honking of a horn. Reed captured vocalizations of wolves whom he knew were seven kilometers away from the recorder. He also witnessed a wolf who responded to its pack from 10 kilometers away.

Humans cannot hear all of what is being communicated but AI -enhanced spectrograms that process recordings of wolves in the wild, can. Reed’s spectrograms, in fact, are able to identify wolf to wolf communication that even the most skilled of wolf researchers like Stahler and Cassidy haven’t even been aware of. What are the wolves saying?

Certainly, Stahler says, a lot more than we think. Wolves have been talking for ages and likely much of it has gone undetected or misinterpreted by earlier iterations of human anthropomorphism. No person has ever interviewed a wolf but countless people have tried to howl like them.

The inability of humans to decipher things like wolfspeak is what caused René Descartes (1596-1650) to conclude animals like lobos had no thoughts and therefore, he reasoned, no soul. In fact, Descartes, credited with being one of the fathers of modern science and philosophy, asserted that wolves and non-human beings were mere machines or automatons moving across the landscape, like AI robots of the Enlightenment. Descartes for all of his certitude and standing was no field ecologist—the holistic ideas of Aldo Leopold would not have jibed with his human-centric perspective— nor could he have ever imagined a device like a spectrograph.

René Descartes, credited with being one of the fathers of modern science and philosophy, asserted that wolves and non-human beings were mere machines or automatons moving across the landscape, like AI robots of the Enlightenment.

An absence of evidence indicating that wildlife is not sophisticated in how it communicates does not mean of course that such sophistication does exist. Descartes’ notions have been roundly debunked by research showing animals have emotions and intelligence and some have highly-developed social orders. Not only that, ethologists say, but behavior is tied to vocalizations. The collaborative work now being done by Stahler, Reed, Cassidy and others in compiling a library of wolf acoustics is putting Yellowstone, once again, on the front lines of yet another major contribution to wildlife conservation. This one could be revolutionary.

Greater Yellowstone is a region were tracking large mammals was pioneered with grizzly bears by brothers John and Frank Craighead and others. It’s also at the forefront of ecosystem thinking based on large landscape conservation.

In 1972, the eminent wildlife biologist George Schaller wrote that “the successful functioning of a society is entirely dependent on its communicatory system.” Stahler, who in 2023 assumed the helm as senior biologist in charge of Yellowstone’s wolf research, which he ascended to after Doug Smith’s retirement, agrees with Schaller.

Before Stahler took over Yellowstone’s renowned wolf program, he oversaw mountain lion research which included the transboundary movements of the big cats ranging inside and out of the national park. American lions, too, engage in loud vocalizations known as caterwauls, but in comparison to wolves, which organize themselves in packs and overtly communicate over long distances, their presence is far more discreet. Lions also are fewer in number. Wolves are coursing predators in that they follow their prey and use howling to position and locate one another across large landscapes; lions are ambush predators and often lie silently in wait.

Thanks to the work of Stahler’s predecessors and current colleagues, and to contributions from people like retired Park Service naturalist Rick McIntyre, who sits at the center of an avid group of citizen wolf watchers, Yellowstone has assembled millions of datapoints relating to wolf behavior. They’ve been gleaned through direct daily visual observation and complemented by radio collars, studying the remains of wolves and wolf kills, using trail cams, examining DNA and scats, and documenting the locations of dens and territories. Each has yielded remarkable insights on their own, Stahler says. But ironically, and until the bioacoustics work began, there’s been a dearth of understanding related to wolves’ most prominent expression as a social species—what they are saying to each other and perhaps to other species in the neighborhood, including people.

McIntyre is legendary for literally spending years of his life out in Yellowstone and taken meticulous notes. His non-fictional accounts of individual wolves and wolf packs, presented in a series of memorable books, have, more than anyone else, brought broad public appreciation for wolves. But, for the most part, his gleaning has occurred in daylight hours and not accompanying his work is a soundtrack.

The same is true of Bob Landis’ epic filming of Yellowstone wolves. Landis, who possesses his own mystique, contributed some of the first audio on which Reed based his initial AI model. As Reed says, “This is a collaborative team effort that goes way back before the present.”

“It’s incredibly important to gather data, as that is the foundation of science,” Stahler told me. “But once you have all of this data, then you have to organize it and try to discern what it means, otherwise it’s just a bunch of information. Gathering data can take a lot of time but pondering it requires, in most cases, a lot more. It can be tedious, painstaking and complicated. What we look for are patterns, and patterns within patterns, how they inform behavior, and how behaviors are interrelated. What we’re hoping to do, with the help of people like Jeff Reed, is add in the acoustical dimension which has been missing. And most importantly cut down on the amount of time it takes for patterns to be recognized and then applied to other data.”

As an illustration of how the field of listening to animals has grown into an merging line of scientific inquiry in this still-young century, there’s the Acoustical Society of America, which publishes a peer-reviewed journal. The organization was actually founded in 1929 by three physicists with a primary focus on sounds created in the human environment and in recent decades has expanded to include multi-facets of nature.

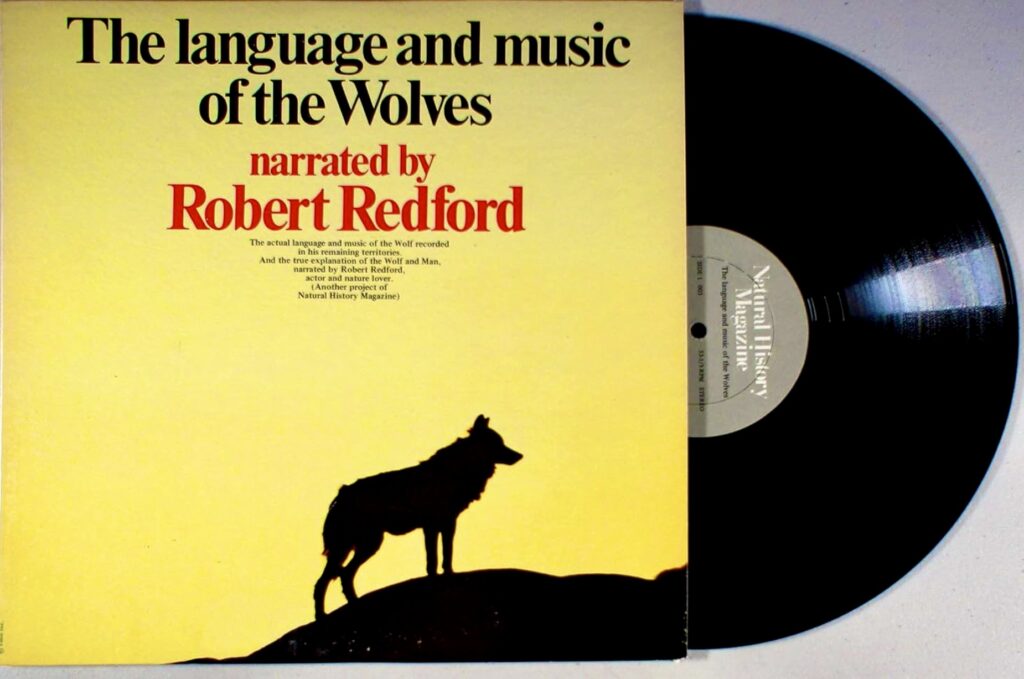

Bioacoustics entered the arena of pop culture when, in 1970 bio-acoustician Roger Payne produced an album on vinyl, “Songs of the Humpback Whale” that sold over 100,000 copies and became the best-selling environmental album in history. That was followed, a year later, with Robert Redford narrating an album “The Language and Music of the Wolves” produced by the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

It would take another quarter century before Yellowstone had actual wild howling wolves on the ground and roughly another 20 before bioacoustics was advanced as an innovation in studying large terrestrial species. In 2019, a peer-reviewed article was published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America titled “Tracking cryptic animals using acoustic multilateration: A system for long-range wolf detection.” Its authors Arik Kershenbaum, Jessica L. Owens and Sara Waller highlight the emerging importance of work being done with Yellowstone wolves.

“The study of animal behavior in the wild requires the ability to locate and observe animals with the minimum disturbance to their natural behavior,” they note. “This can be challenging for animals that avoid humans, are difficult to detect or range widely between sightings. Global Positioning System collars provide one solution but limited battery life, and the disturbance to the animal caused by capture and collaring can make this impractical in many applications. Wild wolves are an example of a species that is difficult to study in the wild, yet are of conservation and management importance.”

To test how effective remote acoustical monitoring could be, the authors deployed recorders that netted 1247 wolf howls during a four month period between November 2025 and March 2016. The array proved effective but an admitted limitation is that the vocalizations could not be pinpointed to exact locations nor to individual animals and packs. This is what Reed is helping to remedy.

While some worry AI may destroy human civilization, this is an example of its huge upside. AI enables us to crunch big datasets. In other words, cost that has previously been a high-wall barrier to discovery may no longer be. Reed gives a very simple example: he can store the equivalent of 80,640 cassette tapes’ worth of audio on a $400 modern hard drive. That’s what it takes to store the massive data they collect in one year.

All of the above is being conducted under the banner of what’s called the Cry Wolf Project, a collaboration of Yellowstone wolf research led by Stahler and partially supported by academic researchers across the globe stretching from Professor Joanna Lambert at the University of Colorado-Boulder to Kershenbaum at the University of Cambridge in England. From the private sector there’s Reed, who has a company called Grizzly Systems and citizens associated with the Wild Livelihoods Business Coalition.

Reed says the initial phases of the Cry Wolf Project have proven its promise and were more investment from the public and private sector to materialize, it holds incredible potential to, metaphorically speaking, paint a fuller more panoramic picture of wolves. He notes that Project CETI, which is studying whale communication and getting lots of media coverage for it, is funded with more than $30 million. “We’ve accomplished what we have with wolves leveraging only $25,000,” Reed acknowledges. As a kid who grew up in the West, he’s proud of that efficiency, but acknowledges it will take more to get to where he wants the project to be.

Stahler and Reed are effusive in praising the pioneering work of John and Mary Theberge and Michael Runtz, Canadian researchers who have been studying wolf vocalizations, especially in Algonquin Park of Ontario, going back more than 50 years. The Theberges, based at the University of Waterloo, have also applied their knowledge to Yellowstone and had a presence in the park for 24 years. An article that John wrote about bioacoustics for Natural History magazine in April 1971 inspired “The Language and Music of the Wolves” album that Redford provided narration for.

In 2022, a peer-reviewed analysis they authored appeared in the Canadian Journal of Zoology and titled “Triggers and consequences of wolf (Canis lupus) howling in Yellowstone National Park and connection to communication theory.”

Whether one is a devoted wolf watcher or a tourist family entering the Lamar Valley on vacation and happening for the first time upon the lines of people with spotting scopes tracking pack movements, it’s titillating stuff to consider. The Theberges analyzed 504 wolf howl events that were observed over as 16-year period. “We related our results to two general theories of animal communication: that vocalization is more about communicating emotional/motivational states than a purposeful transfer of detailed information and that flexibility in use of long-distance vocalizations has been important to overall behavioural plasticity and advanced sociality in non-human primates and large social carnivores,” they wrote. “In our study, half the howl events were triggered by 12 different environmental or social situations, most of which generated levels of anxiety. The remainder were non-triggered, apparently motivated internally but in contexts that reflected basic adaptive drives such as bonding and pack coordination. Approximately half of all howl events elicited either a change in sender activity or responding howls or travel from distant wolves, which we quantified. Wolf howling was inconsistent (low percentage of occurrence) in most behavioural contexts, hence demonstrating flexibility and social discrimination in its use. Thus, both theories were strongly supported.”

“It is interesting that public interest has expanded in the subject just now due to the potential for ‘decoding’ that may exist with AI,” John told Yellowstonian. “We are working with Jeff Reed to see what can be made of our recordings by matching them to environmental/social situations we analyzed. And we are making periodic field trips to Yellowstone to see what we can work out of what we have called ‘yipyap howl events’ that simultaneously seems to express strong and at the same time contrasting affective (emotional) states.”

Early in their career in Canada, as part of a wolf tracking project, they employed radio telemetry and collared wolves but quickly realized it had limitations, namely that it only showed the positions of individually collard animals. John Theberge told a documentary filmmaker that they could locate larger numbers of animals by emitting howls themselves and getting wolves to respond. Through this, after decades, they were able to ascertain general insights but not specifics. The Theberges long ago picked up on something else, that within the mellifluous range of howling are distinctive notes and changing chords that sometimes flow through howling events. People might not be able to tell the difference but they say wolves can.

The couple contributed a small section to the definitive multi-author book, Yellowstone Wolves: Science and Discovery in the World’s First National Park published at the University of Chicago Press in 2020. and edited by Doug Smith, Dan Stahler and Dan MacNulty. “Wolves are notably expressive of emotions,” they observe. “A wide range of wolf sounds, such as whines, moans, whimpers, snarls, growls and yelps accompany various emotions such as distress, aggressiveness, fear, anger and submission. In addition, wolves convey emotions through rich repertoires of body postures, tail positions and facial expressions.” Referring to what the Theberges call “inappropriate howling,” they remind how unwise it can be for loquacious wolves to erupt and give away their location, especially a den site, if rival packs are present or for interlopers moving through a different pack’s territory. As of the book’s publication, “foreign” wolves had gone to den sites of resident wolves on six different times and killed the local inhabitants.

Stahler mentioned the work of biologists Vicente Palacios and Bárbara Martí-Domken who compared howling rates during the pup-rearing season across North America (including Yellowstone), Asia, and Europe. They demonstrated that frequency of howling depended on area, pack size, and density of people living nearby, being less where more people live, perhaps in response to perceived risks of living near humans. An exception was high howling rates in Yellowstone–where wildlife are protected, few people live, but many hundreds of thousands of visitors are present throughout the summer.

Based on personal experience, and in digesting the body of scientific literature, Stahler describes the factors which lead into fully amped-up chorus howls as a “contagion,” in that after a single signaling cue made by one wolf, the enthusiasm infectiously spreads among other pack members who contribute to the choir.

“One member gets up and starts howling. Then others rise and they start rallying together. Tails are wagging, their heads tilted back. They’re jumping on each other and running back and forth,” Stahler says. “There’s an emotion content and its related to their family. Whatever the expressions of emotion are, and we don’t necessarily know, you’d have to be an emotionless robot as a human to not to feel a sense of excitement yourself.”

As he says, it’s clear that when wolves emit howls they elicit a response, but unclear is what they are saying in reply. Is it: “Hello, stranger, we’ve not heard your voice before. Who are you?” or perhaps, “This is a warning: you’re entering out territory and it’s best you move on.” Or, maybe, “Your voice sounds sexy. Maybe we ought to hook up.” In this short video, Reed discusses how three wolves from different packs were engaged in vocal courtship in Yellowstone during the 2024 winter breeding season.

Divining insights is different from scientists being able to claim they can read the minds of their subjects, Stahler notes. Regarding wolves and other animals he’s studied, like cougars, they are always sending out clues and the challenge for humans is trying to decipher their meaning.

In Mech’s forthcoming book, The Ellesmere Wolves: Behavior and Ecology in the High Arctic, he highlights how howling female wolves on Ellesmere Island use vocalizations get a male partner to come join on a hunt. “It’s a howl of persuasion,” he says. “I don’t doubt that the kind of high tech analysis coming out of Yellowstone will be able to identify distinguishable differences in howling that happen, for example, during the breeding season.” Reed showed me an example of what he thinks might be a young wolf actually trying to learn such a “sexy” howl.

Literally, the audio recordings in Yellowstone already have enabled researchers to bear witness to young wolves coming of age, finding their voice in the pack. And, in many ways, it was no different from the exuberant racket that human kids make on a playground. They’re in a phase of hyper-learning, getting prepared for life in the real world. Central to their education is knowing how to speak the language tethered inseparably from their survival.

Beyond dispute, based upon his thousands of hours of AI processing, is that if you’ve heard one wolf howl you’ve not heard them all, Reed says. Vocalizations that sound the same to our ear probably have nuanced subtleties not only in pitch and timbre but context in which they are delivered. Do wolves have dialects that vary from region to region? Are there lilts and accents? Is there a pecking order for who howls when, and what? If two pups are wrestling over an elk bone and if one sibling says the playful equivalent of “get lost” to the other, does that same bark have a very different connotation when it’s an adult pack member patrolling the boundary of the territory and intersects with a trespasser?

When Reed ponders such things, its’ through a different lens than Stahler and Mech do. He’s thinking of how the eminent Noam Chomsky, Benjamin Lee Whorf, George Lakoff, Edward Sapir or other towering linguists might try to explain what’s going on, particularly if spectrograms can be paired with observed recurrent behavior.

In 2013, Chomsky, the MIT professor emeritus, appeared at a conference and said that animal language is, essentially, bullshit. Count Chomsky in the category of skeptics who does not think wolves have a language. Language ought not be invoked as a proxy for ability to communicate or display what he calls “signaling systems.”

“The reference to animal language is puzzling. The question of whether animals have language is too meaningless to deserve discussion. They have communication systems. Bacteria communicate. You could argue flowers communicate since they provide information to the insects. In fact, communication goes on all over the natural world. Is that language? It’s on a par with [asking] whether submarines swim.”

“The reference to animal language is puzzling. The question of whether animals have language is too meaningless to deserve discussion. They have communication systems. Bacteria communicate. You could argue flowers communicate since they provide information to the insects. In fact, communication goes on all over the natural world. Is that language?”

Linguist Dr. Noam Chomsky

True intelligence, Chomsky says, is demonstrated through moral thinking. He rejects the assertion that animal language is parallel or tantamount to human language; in fact, he claims animal language, at least in the way he thinks about language and how animals practice it, does not exist. It is instead a form of communication and even with species that exhibit advanced behavior, they are communicating, not possessing or exhibiting the kind of consciousness humans have that can be expressed through language. As he notes, language is not only externally expressing what is on our mind; it is present too when we are walking down the street, thinking to ourselves and having an internal conversation in which concepts and processed through words. Humans can engage in self-reflection and are able to ponder our own place in the world, searching for meaning? Language is a means by which we do this and try to make sense of things. Is that how non-human animals operate. Chomsky remains highly skeptical.

Is Chomsky a speciesist engaging in specist argument? “I believe Chomsky is wrong, as do many others by the way of Eve Fedorenko and Tecumseh Fitch, two eminent linguists, when he [Chomsky] ties ‘thought’ to ‘language,’” Reed says. “He admits that animals communicate and can have advanced behavior. Where he differentiates us from them is in the ability to be ‘recursive’ in the way we use language to express our ‘thoughts.’ Recent studies in crows show that they can perceive recursive objects in lab studies, but I agree with Chomsky that it hasn’t been shown yet that animals use recursion in actual oral communication. So, Chomsky simply defines “language” as the ability to do “recursion” and therefore excludes animals. He might as well just say “recursion.” I would argue that animals have language without recursion, at least based on the current state of research.”

“At present we tend to side with Chomsky that wolves, as well as all other non human species, do not have a language if you define the word language properly—vocalizations that have three key properties: intent to communicate, semantics and syntax,” John and Mary Theberge say. “But we have the opportunity now to look at our years of collection situation-specific recordings and see if there may be more in them than emotion/drive expression.”

It’s worth noting that in the June 2024 edition of the prestigious science journal Nature, Fedorenko is lead author on a paper titled “Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought” which seems, on the face of it, to add validity to what Reed is saying.

Chomsky has said he doesn’t want his perspective to be misinterpreted as refusing to believe there isn’t a lot of amazing things going on in the animal world. As he notes, bees exhibit all kinds of complex cooperative behavior, including the “waggle dance,” and they are able to communicate with plants on whether its time to be pollinated and, in turn, ready for bees to carry nectar back to the hive Chomsky does not quarrel with those whose research suggests animals have both intelligence and emotions. Like Descartes’s earlier notion, Chomsky’s position has attracted plenty of well-known detractors, including Jane Goodall who became famous studying the interactions of chimpanzees.

Dan Stahler says that he, on countless occasions, has witnessed expressions of sentience—intelligence and emotions— in Yellowstone’s wildlife, from wolves and cougars to other animals. In a recent story in Yellowstonian, ethologist Marc Bekoff talks about sentience in the animals of Greater Yellowstone. Studies also have demonstrated that elephants give each other names in referencing each other as do parrots. Is recognizing a personal identity in another individual not a form of language?

° ° ° °

Foremost, the Cry Wolf Project has a mission of elevating public understanding of wolves. True enlightenment has always been a response to ignorance; to the notion that we kill the things we fear and destroy the things we don’t understand because we portray them as a threat to us, without realizing that education can help us overcome our fear of what had previously been unknown.

True enlightenment has always been a response to ignorance; to the notion that we kill the things we fear and destroy the things we don’t understand because we portray them as a threat to us, without realizing that education can help us overcome our fear of what had previously been unknown.

In their paper published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, mentioned above, the three authors noted that “wolves and other wild canids have considerable significance in terms of their impact on human activity, their ecological and conservation importance, and their role in the public perception of wildlife and rewilding. Large scale monitoring of wild canid activity has an important role to play in balancing these often conflicting concerns, and we believe that the technology proposed here can be usefully applied by researchers and wildlife managers to provide information necessary to strike such a balance.”

Indeed, Reed notes, it’s possible that by untangling the messages that wolves are sending to each other, recorded vocal warnings that wolf packs make to other packs, telling them not to enter their territory, could be used, paradoxically, by ranchers as a non-lethal deterrent to wolves and coyotes living in the vicinity of domestic cattle and sheep.

But he remains skeptical, until it is proved otherwise, that wolves won’t habituate to playbacks because they are inordinately perceptive and smart. They aren’t fools. What he does say is that if one is going to try to deter a wolf from livestock settings by using wolf howls played through a speaker, base your technology on hard science. “If you’re going to do it, do it right, not half-ass,” he says.

Although it’s way too early to tell, there is speculation that noise connected to humans may affect wolf communication. For example, the recording devices pick up a lot of residual sounds, including that of vehicles and airplanes passing above the park. After a visit to Jackson Hole last fall where he presented information about the wolf project at the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative’s wildlife symposium, he wondered how the presence of the commercial airport in Grand Teton National Park could be impacting, perhaps dampening, inter-and intra- animal communication. He pointed out that over 50 commercial airplanes moving through the sky daily can be picked up by each of his recorders in Yellowstone.

Descartes was, as each of us is, a product of his own time. His perspective was shaped by what happened just prior to his own birth. During the Dark Ages as waves of the Black Plague swept across Europe killing millions, wolves were known to scavenge from human bodies before corpses were burned or buried. Thus, a widespread negative association ensued. On the high plains of the US, European explorers moving through vast herds of bison during the 19th century noted how wolves, fearless yet showing no aggression toward people, were capable at feeding on bison calves or converging upon carcasses after successful indigenous hunts. Indeed, native peoples—who knows how much earlier in time—had tamed wolves and honored them in the names of warrior clans out of admiration for their behavioral attributes. It was only settlers of European origin, carrying with them negative inherent biases from the Old World, that did—and still do—relentlessly target wolves and other species for annihilation in order to wipe landscapes clean of species that pose a threat, or compete for grass, with their non-native domestic livestock.

The most ardent haters of wolves have admitted that their attitudes changed after they allowed themselves to sit still in the wild, watching family groups of wolves interact and hear their chorus howls. What sets Yellowstone and only a few other areas apart are that wolves are able to be studied for the most part without menace or ongoing lethal persecution and intolerance from 21st century humans. Unless, of course, they move beyond the park boundary and then are subjected to state sport hunts. In the winter of 2021-2022, as a result of Montana’s much-maligned hunting quotas, around one fourth of the park’s wolf population was killed by hunters and trappers, including the destruction of an entire pack. It created trauma and social turmoil for park wolves. Hardest hit were the Junction Butte and Phantom Lake packs.

Reed, who has hunted deer and elk his whole life and identified as a political conservative, admits he has changed his own thinking about wolves, based on a growing love for biodiversity and the glaring, irrefutable insight he came to, that wolves delight humans and also make people money because visitors want to see wild free things, not zoo versions. It’s why he helped found the Wild Livelihoods Business Coalition comprised of businesspeople who value wolf conservation, including the fact that wolf watching adds about $80 million annually to the economy of communities located near the north end of the national park. It’s sustainable as long as wolves stay alive, remain visually observable, and packs healthy. He believes that even Descartes and Chomsky might soften their imperious dismissal of animals, as allegedly possessing no innate spirit that goes beyond language, if only they spent time in the company of wolves.

“What we have are these amazing animals moving in and out of our first national park engaged in amazing behavior we’re only now coming to better understand, and for those of us fortunate to live in Greater Yellowstone, it’s happening in our own backyard,” Reed says. He doesn’t believe that AI diminishes the mystery of wolves; rather it can help bolster human awareness of—and respect for—complicated social behavior reflected in a natural soundscape. He wonders how the vocalizations of wolves changes as packs disintegrate. Do their members turn noticeably less vocal before the packs themselves simply go off the air?

Sadly, Reed contended with that question the hard way when he saw what he describes as, harmonically, “a near perfect chorus howl” appear in one of his spectrograms. He experienced it when the Rescue Creek Pack broke out in song at night on New Year’s Day 2024. After listening to it, he realized that the voice of the alpha male, which he had heard so many times during the previous year, was absent from this group howl. “He had gone missing in November,” Reed said. “A wolf’s life is a hard one as it is. It is hard for me to listen to their silence.”

° ° ° °

You can listen to the recording of the Rescue Creek Pack that Reed references above in the video below. It features four different packs. The Rescue Creek chorus howls are in the lower righthand corner.

ENDNOTE TO YELLOWSTONIAN READERS: This is the first of an ongoing series of stories that will share new insights emerging from the Cry Wolf Project including an exciting special announcement coming soon. For those who would like to learn more about the wolf bioacoustic work in Yellowstone, click here to watch a presentation Jeff Reed gave to Jim Halfpenny’s regular speaker series, A Gathering of Naturalists, in Gardiner, Montana.

DO YOU VALUE STORIES LIKE THIS? If yes, please consider making a contribution to Yellowstonian to help us give you more in-depth reporting in the public interest. Your support matters greatly to us and is much appreciated. Devoted to delivering fact-based conservation journalism that celebrates the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and wild places, Yellowstonian is a special project of Artemis Institute, a 501 (c) (3) registered with the state of Montana. All contributions are tax-deductible to the extent of the law.