by Todd Wilkinson

They say it’s never wise to scream into the front end of an approaching hurricane, expecting that it will bend before your desire for it to politely shift direction. It can be especially problematic if there is no backup plan.

Had Doris Fischer gone to work in Salt Lake City, Denver or Boise, her priorities as a county land use planner in the West might have been different. She could have focused her attention on addressing the usual checklist of technical skills they teach those in her profession at university, such as how to efficiently deliver urban services or strive to guide growth in orderly ways out into the suburbs.

But having to consider the well-being of a world-class concentration of wildlife?

Or protecting the visual soulful ambiance of a famous river?

Or keeping people on the land because they represent the heart of local identity and community, in addition to possessing the all too valuable memory of place?

In a city, a planner need not have such worries and, indeed, most planners these days have little to no training in pondering the impacts of development on ecology. Nor for that matter, do most architects, realtors, builders and hotshot capital investors who calculate profit down to the square foot.

When Fischer was hired to be lead planner for the mostly-rural and geographically-massive Madison County, Montana in the 1990s, a storm was about to bear down on corners of that county’s mountains and valleys—still wild and pastoral places—holding iconic native wildlife species and stupefying views.

Behind the leading front of new development pressure soon to barrel in and bringing with it sprawl wasn’t modest financing being advanced by local banks. The amount of capital soon to be arrayed and still flowing in today—calculated in the billions of dollars—would come from international investment firms thinking many steps ahead of where the mindset of local elected officials was. Some of their investments had built skyscrapers in major cities or had Vail, the Hamptons and Hilton Head as the models of how leveraged development is supposed to work.

Local yokels believed native Montanan and retired national TV news reader Chet Huntley when he said he wanted to give Montana a decent weekend retreat for skiing at Big Sky, which had been, up until the 1970s, an undeveloped, remote side drainage feeding the Gallatin River and US Highway 191 populated by a few historic dude ranches. There also were outfitters who guided clients into the Madisons and nearby Gallatin Range in search of trophy wapiti (members of the world renowned Gallatin Elk herd) and other species like mule deer, bighorn sheep, moose, and bears). Grizzly hunting ended in Greater Yellowstone in 1975 when bears were federally listed but looking back, scientists say, the West Fork of the Gallatin, where Big Sky is bursting at the seams, would’ve made excellent habitat for today’s recovering bear population and refugia for many species.

Despite what Huntley said, people who followed in his wake, using Colorado destinations like Vail as their reference point, knew fortunes would never be made selling lift tickets and apres skiing drinks at the bars. Big money is generated by selling “raw land” and luring in buyers or jet-set visitors by dangling luxury amenities, along with the moxie of hip exclusivity. No one knew that better than Tim Blixseth when he shrewdly acquired real estate near the ski resort owned by Boyne of Michigan. Today, one can find hotel digs renting for many thousands of dollars a night and drink bottles of fine wine that retail for as much as working class Montanans earn in a couple of days.

What Big Sky really did, observers say, is it became a magnet for other investors and property hunters—some of whom have conservation and maintaining the wild character of Montana in their hearts but there are others on the prowl. Knowing how we got here is important. Past can be prelude.

As Fischer says, looking back, there was a window when Madison and Gallatin counties had an opportunity to force Big Sky to conform to Montana values rather than becoming an enclave that today stands in contrast to the modest sensibilities that appeal to so many of her citizens. But the window opened and closed.

Often, planning staffs answer to locally-elected civil servants who have spent much of their lives in places like Madison County, believing that growth only happens in quaint, slow-moving terms. Many subscribed to mantras never really tested, such as “all growth is good;” that communities and rural landscapes are changeless; that every boom goes bust; and that public costs associated with accommodating economic bonanzas pay for themselves in tax revenues. All of those myths have been proved false. County commissioners over the years, too, expressed incredulity that shrewd speculators could ever take ag or forested land selling for a few thousand dollars an acre, at most, and then break it down into smaller tracts, hawking them for millions; not doing it just once, but over and over again. Covid helped fuel the frenzy.

Today, reality has disabused most locals of many of their earlier provincial (and naive) notions.

Fischer had a front row seat to all of it. She saw ignition points for explosive growth in Big Sky, which straddles by quirk of human cartography both Madison and Gallatin counties in southwest Montana, the latter being the county encircling Bozeman. How did she land in the position?

Fischer, a good student, went to Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts pursuing undergraduate degrees in psychology and political science. She got a job with the National Recreation and Park Association, a trade organization, in Washington DC. She quickly got a sense that when towns are dealing with growth issues, the first things to be cut from budgets are libraries, parks and recreation programs—the very amenities that are important to social cohesion. It led her to become interested in community planning, and to the vaunted graduate planning program at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

“I learned a lot but nothing about the reality of being a community planner as far as the level of conflict that might be encountered and what it’s really like to wrestle with issues that affect peoples’ lives,” she said. And then she undertook what she calls a “yo-yo” career path. She spent the summer of 1989, after the historic forest fires, in Yellowstone working as a park planner. “It was a fabulous experience and after a few years I went back to Wisconsin, then to Missoula and worked in the city/county planning office for five and a half years.” Part of being in Montana had to do with the fact that her mate was a community activist and philosopher involved with Missoula civic issues. Not long afterward they moved to the Ruby Valley in 1995 and she’s been there for the last 30 years, staying even after her partner’s death. “I was a very pennyless journalist writing for The Madisonian and Dillon Tribune and then got interested in planning again.” Being a journalism helped provide a critical frame for thinking about planning issues.

Madison County, then in the early stages of pondering planning, hired Fischer as a contract planner in 1997, working with the planning board and commissioners on its first comprehensive plan. “It was a wonderful experience, very positive,” she says. “People were having an opportunity to gather and talk about the future.” She worked for the county for nine years, the last stretch as its chief planner. She left, feeling burned out dealing with a multitude of pressures, competing interests and lack of resources.

Later, she was hired by Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks as its first-ever planner assigned to work with towns, counties and landowners. “For five years, I drove all over the state. It was a great job dealing with issues affecting public and private lands important to wildlife. But while I was on a leave of absence to help my partner (who was dealing with the final throes of ALS) the legislature proposed eliminating my position because some legislators didn’t like FWP being involved with planning. I realized it was probably time for me to do other things.”

Not long ago, Yellowstonian had a conversation with Fischer, whose perspective ought to be essential reading not only for those who care about the wild nature of place in Greater Yellowstone, but elected officials and planning staffs in any mountain valley hamlet. Perhaps Fischer’s observations could help prepare them for what’s coming next.

A Conversation with Doris Fischer about Missed and Potential

Opportunities to Save the Northern Rockies’ Rural Character

Todd Wilkinson: Many friends and acquaintances who collectively have centuries’ worth of practical experience in land use planning praise your work as a professional planner with Madison County, Montana. They say you and members of the Madison County planning board and a few commissioners actually tried to do the right thing. It’s clear today that most counties in Greater Yellowstone are underprepared, understaffed and under-informed to deal with growth issues now upon us.

We often hear the term “smart growth” bandied about amorphously but its execution relies upon a kind thinking that wisely considers all of the variables, especially in a rarefied ecosystem like this. Its essence is holistic thinking that prioritizes community values over their naked exploitation and heeds the value of nature, particularly in a state notoriously abused by the greed of Copper Kings who left despoliation in their wake. What would you call “intelligent planning” and why does it matter?

Doris Fischer: Planning is “intelligent” when it becomes a deliberate practice of community discussion and action. Such practice is most effective when based on:

- Collective learning and goal-setting;

- Widespread commitment to prioritizing the common good over self-interest;

- Respectful participation by diverse private citizens, public officials, and interested groups such as local conservation districts, service districts (e.g., school, fire, sewer and water) and community and truly-informed conservation-minded nonprofit organizations; and

- Transparent decision-making.

TW: And what would the inverse of that be?

Doris Fischer: Unintelligent planning is reflected in decisions that do not benefit the larger community. The decisions are based on incomplete or misleading “information,” procedural charades rather than honest, open public process, and a bending of rules to satisfy the desires of one group to the detriment of others.

Intelligent planning fosters community unity and capacity to address widely recognized problems and opportunities. Unintelligent planning breeds disunity and inability to accomplish anything of value to more than a select few.

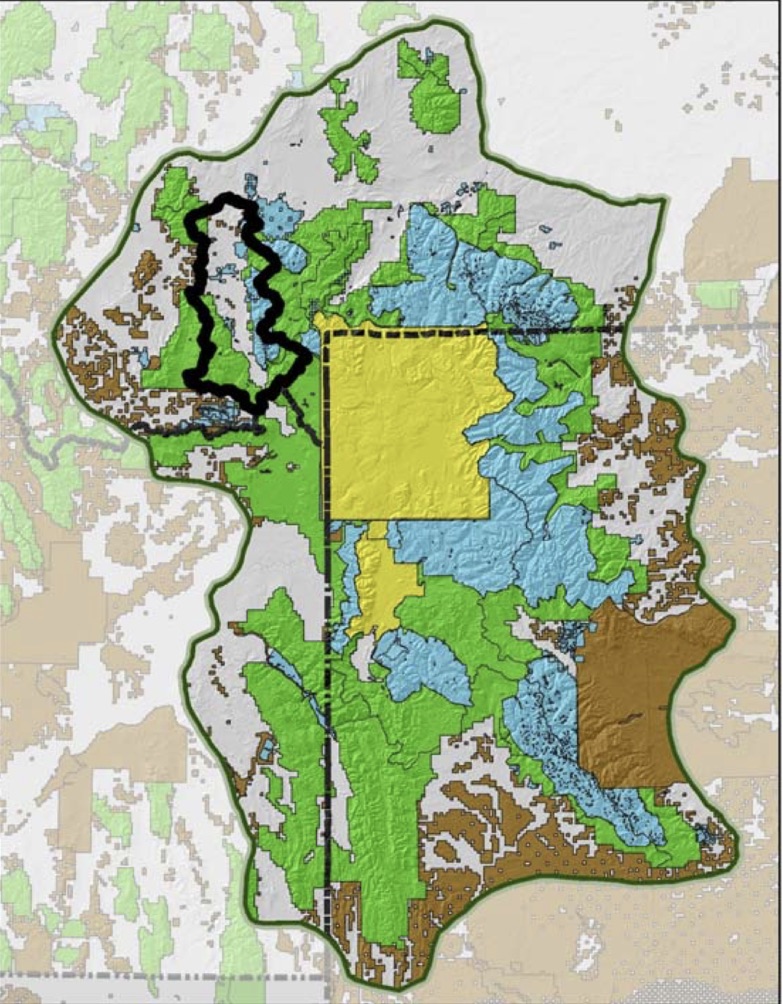

TW: Three decades ago, Madison County, as a government entity, was hailed as being pretty thoughtful and ahead of the curve in terms of anticipating development pressure that was coming. And there were pro-planning legislators elected to the state house and senate. They identified the need to protect watershed corridors from sprawl and solicited scientific opinion from Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks on how to, for example, protect wildlife winter range. Is that a naïve recollection of what happened on my part? When you look back, what were some of the things that caused heightened concern for the future of Madison County and could you ever have imagined what has happened since the 1990s?

Doris Fischer: Timing is everything. Thirty, forty years ago, county residents grew alarmed by the changing character of Madison County. Thousands of acres of open land were being divided through a development-friendly state subdivision law that included several subdivision review exemptions. Hundreds of 20-, 10-, even five-acre lots especially in the Madison Valley were sold sight unseen to out-of-state buyers; many of the buyers were looking for vacation spots, not permanent residences. New houses were increasingly scattered across the landscape, with little regard to adequate road access or water supply.

TW: Indeed, one of the deceiving data points that escapes public scrutiny when citizens think about growth and look only at US Census stats is that a population might be growing slowly but sprawl continues to proliferate because of vacation homes that are built, wreaking permanent impacts that never go away, no matter how long many weeks of a year they’re inhabited. In Park County, Montana, for example, the number of new structures created in recent years surpassed the rise in local population.

Doris Fischer: That’s an issue today in so many valleys around us.

TW: We locals have a rather dim view of people who arrive and pay little regard to longstanding customs and traditions, such as demonstrating humility and not approaching landscape as a stage for declaring “I am somebody” important and thereby erect a trophy home on a prominent promenade that places individual fulfillment of desires above everyone else. Some are oblivious to the specialness of the terrain they’re invading or they don’t care about the community. How did that happen in Madison County?

Doris Fischer: Homes appeared on ridgetops, along waterways, and in the middle of wildlife habitat. The new settlers had limited knowledge of local culture, and many demanded more local government services. Environmental and economic resources, quietude, community traditions, and neighborliness felt threatened even though some of the newcomers brought new revenue and new talents to the area. The influx meant farmers and ranchers could sell their struggling operations for big money; a frenzy of land sales and new developments gripped the county with few sideboards in place to guide the changes.

Homes appeared on ridgetops, along waterways, and in the middle of wildlife habitat. The new settlers had limited knowledge of local culture, and many demanded more local government services. Environmental and economic resources, quietude, community traditions, and neighborliness felt threatened…the influx meant farmers and ranchers could sell their struggling operations for big money; a frenzy of land sales and new developments gripped the county with few sideboards in place to guide the changes.

TW: And how did those in government, to whom citizens looked for leadership, respond?

Doris Fischer: By 1998, the Madison County Planning Board and County Commissioners agreed to hire a planning consultant (me) to coordinate a countywide process of planning for the future. Public discussions were held in communities around the county to identify current threats and opportunities, and brainstorm strategies in response to questions like:

- (1) How do we conserve what we love about Madison County; and (2) How do we minimize the negative impacts of rapid, uncontrolled growth?

TW: An assumption is always that if people just talk to each other more, and hold more meetings over coffee and beers, and explore “shared values,” that conflicts or differences in perspective can be overcome or avoided. That works, except when the real estate industry, developers and investors are playing only to win the day. They aren’t interested in the wu-wu talk of “common ground” and “maintaining a sense of place” because that’s not how they measure success. They’re happy to engage in touchy-feely as long as they know they get what they want in the end and are willing to play hardball, which fewer conservation organizations these days seem willing to do. Consensus and collaboration is still being promoted as an alternative to engagement in contentious planning and zoning issues, but sprawl is still spreading unabated. Are people wiser today or are they just being wishful?

Doris Fischer: Back then, in the 1990s, everyone was encouraged to listen and learn together about the phenomenon of growth, share their own opinions and knowledge, and respect each other’s perspectives. The result was a 1999 County Plan. It contained clear goals and objectives, and recommended new strategies for managing future development. People had high hopes. The plan began to be implemented immediately. It included everything from establishing a county planner position (mine), to forming a “dark skies” citizen task force to come up with design guidelines meant to curb nighttime light pollution, to compiling a “Madison County Code of the New West” guide for newcomers to discuss and illustrate how to co-exist amicably with limited government services, agriculture, and wildlife, to updating county subdivision regulations. The county planning board was an enormous asset to the county at this time and there were good, sincere people serving on it. The county commissioners demonstrated the political will to adopt the plan and put it into action.

TW: Madison County recognized the iconography of the Madison River which flows through the middle of the Madison Valley. What was the thinking behind some of the efforts to put setbacks in place along the river corridor to prevent sprawl from lining the banks? Did those efforts succeed as you had hoped?

Doris Fischer: Well-known as a blue-ribbon trout stream, the Madison River served as a magnet for major land ownership and land use changes during the 1970s and 1980s. Bozeman planning consultant Joel Shouse and the county planning board worked through a process of encouraging conservation easements in the valley and building setbacks along the river, to protect that precious resource.

TW: That’s visionary thinking and it resulted in many large ranches being protected with conservation easements. River setbacks protect the scenic essence of the river, keep structures out of the so-called “flood fringe,” prevent septic contamination and protect wildlife habitat since river corridors are so important for many species. How well received were the recommendations?

Doris Fischer: After several years of watching new land divisions and development occur along the river despite the recommended voluntary actions, the county added river setbacks to its subdivision regulations: 500 feet for the Madison River, and 150 feet along other rivers in the county. To this day, anyone using newer state subdivision law to divide their land for development purposes must adhere to river setbacks—although a few county-approved exceptions called variances have slipped through.

TW: It doesn’t take many county-approved exceptions to undermine the purpose. You mentioned a key phrase, “voluntary actions,” which also applies to developers presented with suggested guidelines offered from state fish and game departments to developers on how to minimize impacts of subdivision on wildlife and their corridors, but seldom are they followed.

Doris Fischer: The major problem with the approach to river setbacks? The building setback along the rivers in Madison County, except now for the Big Hole River, do not pertain to previously subdivided land. Hundreds of still-undeveloped riverfront lots exist throughout the county, mainly in the Madison Valley, and developments on these individual lots are mostly free of a setback restriction.

The major problem with the approach to river setbacks? The building setback along the rivers in Madison County, except now for the Big Hole River, do not pertain to previously subdivided land. Hundreds of still-undeveloped riverfront lots exist throughout the county, mainly in the Madison Valley, and developments on these individual lots are mostly free of a setback restriction.

TW: If all of those lots were built on, the river corridor’s scenic charm and value for migrating wildlife would be destroyed. I remember the rush that occurred among landowners decades ago. They sprinted down to the county courthouse and filed subdivision requests prior to setback provisions being put in place. They wanted to get subdivisions grandfathered and exempted.

Doris Fischer: The 1999 Madison County Plan was followed up by an extensive and very public planning process in the Madison Valley. It culminated in adoption of the 2007 Madison Valley Growth Management Plan. This area plan specifically addresses growth issues in this part of the county. Development close to the Madison River remained a major issue. The area plan recommended that zoning be instituted to apply a science-based building setback more uniformly on future developments in the valley. The Plan was supported by the county planning board and planning staff. The county commissioners adopted it despite opposition by a few influential landowners. My tenure with Madison County ended shortly thereafter.

TW: In a short period of time, Big Sky, nearby, sprung up with one of the highest concentrations of wealth in the country and it’s had multiple negative spillover effects. Your presence as an ecologically-minded planner helped keep awareness about the spirit of the Madison River, and its value to the common identity of the larger community alive. And you had concerns about the creep of Big Sky’s development on wildlife in the mountains. It was based on the premise that everyone gains a lot by being willing to give up a little—and not by seeing land solely for its highest monetizable value.

Doris Fischer: In an effort to implement the river setback portion of this Madison Valley Growth Plan, the county planning office and board subsequently initiated a planning effort to establish a Madison River setback zoning ordinance applicable to all properties fronting the river. Again, that process became very contentious. Despite the planning board’s recommendation to approve the setback zoning proposal, the county commissioners ultimately decided to set it aside. Instead, they agreed to put funds towards a development coordinator position to assist landowners in locating future buildings along the Madison River corridor. The county dragged its feet on funding that position, and I do not know enough about its current status to comment on its existence or effectiveness.

TW: This seems a poignant example of how vision, expressed in an atmosphere of inclusion and goodwill, can get sent off the rails by those who may have hidden agendas, are under pressure to deliver to their investors, or have no interest in seeing a consensus and collaboration process succeeding in practice. Some have also argued that consensus and collaboration seldom gives adequate deference to wildlife and its habitat needs. The process chews up a lot of people’s time and resources and can breed cynicism. As one prominent originator of consensus and collaboration in Greater Yellowstone has said, we need more brave action and fewer meetings because what needs to occur is obvious. And that is zoning.

Doris Fischer: That happens, a lot.

TW: In terms of planning, the growing elephant in the room is Big Sky that has exported its affordable housing problem to the Gallatin Valley near Gallatin Gateway where sprawl is rapidly destroying the ability of the famous Gallatin Elk Herd and other species to move. During the 1990s three major high-end residential developments—The Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks and Moonlight—became game changers in expanding the size of the rural development footprint and amping up real estate speculation in Big Sky. What were your concerns when those developments were first submitted for review? Many people may not realize it, but Big Sky, in addition to being unincorporated (which means there is no municipal government) covers portions of both Madison and Gallatin counties. What is problematic about that?

Doris Fischer: Buildout of the Big Sky Resort and Moonlight Basin Ranch in Madison County east of Ennis was well underway in the Mountain Village area before 1990. Yellowstone Club’s Master Plan was subsequently approved shortly before I hired on as county planner. Those three Master Plans outlined several future development phases, thereby setting the stage for major expansions of the resort area.

TW: Some elected officials believed they were about to have endless riches in tax dollars rained down upon them, filling county coffers. Unfortunately, reality intervened. There is a lot of high-minded talk about sustainability, but what is being sustained in the context of Big Sky’s ecological setting?

Doris Fischer: County commissioners were impressed by the increase in property tax revenues pouring into the county in the beginning. It was easy for most Madison County residents to feel far removed from Big Sky, as though what was happening there did not matter. That was naive. But yes, we were happy to take their tax money, especially the Ennis School District.

TW: And, then, massive earthmoving commenced and it’s still going on.

Doris Fischer: Spanish Peaks was master-planned under my “watch.” I’m not proud of it. I saw my job in handling the proposal—the fourth major Master Plan/development in the Mountain Village area of Big Sky —as damage control rather than growth management. The opportunity to manage Big Sky growth effectively had long evaporated, in my view, even back then. That train had already left the station.

Spanish Peaks was master-planned under my “watch.” I’m not proud of it. I saw my job in handling the proposal—the fourth major Master Plan/development in the Mountain Village area of Big Sky —as damage control rather than growth management. The opportunity to manage Big Sky growth effectively had long evaporated, in my view, even back then. That train had already left the station.

TW: And now there’s all this noble talk of erecting wildlife crossings over US Highway 191 as meanwhile there seems to be little reflection on what impact more development and rising population is going to have up there. Indeed, the magnitude of construction, with no central plan or force guiding it, was unruly. Reporter Ray Ring captured the chaos in a long-form investigative report for High Country News in 1997. Even today, he regards Big Sky as the poster child for refuting arguments brought by free-market environmental think tanks who claim enforceable planning and zoning is a bad thing. Developers in Big Sky took advantage of its remoteness and split jurisdiction between Gallatin and Madison counties, yes?

Doris Fischer: The two-county shared jurisdiction over Big Sky makes for awkward governing, to be sure. Land use regulations in Gallatin County are different and more extensive than those in Madison County. Developers, landowners, workers, government officials and staff all have had to live with the fact that what is acceptable in Gallatin County may not fly in Madison County, and vice versa.

Perhaps the two public service providers able to bridge the gap most efficiently have been the Fire District and Water/Sewer District. The two County Sheriff Offices also seem to work well together. Madison County Commissioners are often pressured by Big Sky developers to pay more in local services, including bus shuttle services, in order to match Gallatin County’s financial commitments.

TW: There’s kind of a similar jurisdictional conflict with Grand Targhee Resort in the Tetons because some of the operation is in Teton County, Wyoming while other aspects of development are in Teton County Idaho. Independent planners I know have described the evolution of Big Sky as schizophrenic, including a manic approach to building occurring on top of a sensitive environment that previously had high wildlife values and still has forested terrain prone to wildfire. Describe how the duality of two different counties having partial jurisdiction played out.

Doris Fischer: Gallatin County works within the regulatory framework of zoning, subdivision regulations, and state sanitation and water standards in order to “manage growth” in Big Sky’s Meadow Village area. Madison County has no zoning in the Mountain Village area and Big Sky is unincorporated so there’s no elected municipal government that has to answer to citizens the way towns do. We in Madison County have only subdivision regulations, state sanitation and water standards, and, I believe, a more recent building plan review step prior to the start of construction on a particular lot. I think zoning by Madison County prior to the first years of Big Sky Resort and Moonlight Basin Ranch master planning could have established a carrying capacity for future growth, i.e. where building is located, how much, and under what terms. Instead, the development-specific master plans were utilized as a weaker planning tool. There was little regard given to cumulative effects and the results speak for themselves.

TW: Did you have a good sense of the intense kind of real estate speculation that is still roaring in Big Sky and, from a planning perspective, what would you have done differently if you could have?

Doris Fischer: The pace and scale of Big Sky development in Madison County was unlike anything happening elsewhere in the county. “Flipping” real estate—buying at one price one day, selling for a higher price the next— had become the norm as my tenure with Madison County ended. Real estate values were escalating beyond belief. The monetary stakes were enormous.

The pace and scale of Big Sky development in Madison County was unlike anything happening elsewhere in the county. “Flipping” real estate—buying at one price one day, selling for a higher price the next— had become the norm as my tenure with Madison County ended. Real estate values were escalating beyond belief. The monetary stakes were enormous.

TW: That creates a mad scramble and all kinds of growth issues and unintended negative consequences.

Doris Fischer: One example of this: The development manager for Yellowstone Club once fumed to me that the county’s weeklong delay in signing off on completion of a particular condition of subdivision approval was costing Yellowstone Club several million dollars each day. And, in wry jest, he announced he was wearing wire around his wrists to keep himself from slitting them.

TW: What would you have done differently?

Doris Fischer: First, I would have strongly argued for using some of the property tax revenue windfall coming from Big Sky to set up a two-county planning office in Big Sky. It was difficult for county planning staffs to trek from Bozeman and Virginia City routinely to monitor buildout of the exponential growth. “Enforcement” of existing rules was sporadic at best. Hence, problems with water quality, wildfire protection, wildlife, and transportation services, including emergency access, became routine.

Second, I hope I also would have organized a multi-agency Big Sky council to advise both county commissions on issues like wildlife habitat conservation, water quality, and lack of adequate employee housing. I would have pitched to this council, the planning boards, the county commissions, and Big Sky landowners/businesses the idea of forming a Big Sky land trust, initially endowed by Big Sky property tax revenues to mitigate the costs of unprecedented growth. In this case, the huge toll on critical wildlife habitat including wetlands and land for affordable housing projects could have been purchased. Development impact fees should have been more seriously considered, although at the time the legislature seemed dedicated to making that tool more and more difficult to use.

Paltry efforts perhaps, but better than operating in a wholly responsive, defensive, damage control mode, which is what we had and still have now.

TW: As scientists say, the loss of wildlife habitat in that formerly wild corner of the Madison Range can never be reverse engineered and neither can greenwashing create an alternative reality. You left your job with the Madison County planning department in 2007. At the time, the planning department was overwhelmed and understaffed. It’s a scenario that is abundantly present today in Bozeman and Gallatin County. In order to adequately plan and deal with growth in an orderly fashion, what are some of the things most needed in order to give staff the resources they need and avoid burnout?

Doris Fischer: Commit more money from the county’s general fund coffers to the planning office; become less dependent upon the project review fees paid by private developers. Developers “pay to play” and, of course, expect things to go their way in return. Generally, planning offices need more staff and more cross-training of the staff.

TW: Amazingly, we live in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, with some of the highest native wildlife values in the temperate zones of the Earth. And GYE counties often claim they don’t have adequate resources to do the most basic tasks, let alone have seasoned professionals on planning staffs tasked with monitoring/scrutinizing the negative ecological affects of development on assets that set the counties apart in the world. That seems messed up. It also explains why wildlife is only treated as an afterthought.

Doris Fischer: Counties need to hire planning staff with a greater level of planning education and/or experience in understanding large landscape conservation and the role that rural and working lands play. This means, of course, that county commissioners will have to pay them a decent wage.

TW: There’s the adage that you get the level of expertise that you’re willing to pay for.

Doris Fischer: Planners do not expect to get rich over the course of their career, but they do deserve just compensation, especially in counties accommodating affluent individuals and businesses that can afford to pay impact fees. When I left county employment, the planning director’s salary was doubled in order to attract qualified applicants. I wholeheartedly supported this salary increase.

TW: A criticism I hear often is that those involved with planning in our region lack awareness of how the nature of place is different here. It’s what gives our valleys context and can be a roadmap for how to approach growth, not a hindrance or nuisance, when is how developers like to portray it. How can that change?

Doris Fischer: Any planning board members and county commissioners should receive rigorous and regular training on the principles of planning, state laws, local regulations, public process, real estate development, wildlife habitat conservation, transportation, emergency services, environmental protection, and the like. During my tenure, collective learning was critical to each of us being able to do our “jobs.”

TW: There is a huge gap between the large number of conservation NGOs focused on public lands and the number involved with private land use planning. And the fact so few of the NGOs are engaged in private land use issues also has huge implications for wildlife on public lands. I heard this expressed by the leader of a prominent conservation group in Bozeman, that his group doesn’t engage in private land planning and zoning issues “because it’s too hard.” How would you fix that?

Doris Fischer: I would nurture working relationships with local and state agencies and nonprofit groups interested in the co-existence of growth and conservation, beyond just thinking about easements. County commissioners need to support their planning staff and planning board members when they raise issues about impacts of development on nature. Controversies over land use issues are inevitable, and it is most heartening when your employer, the county attorney, sanitarian, and community partners defend you. If you’re lucky, someone may even commend you for doing your job.

TW: When you are in Ennis and you look eastward toward the Madison Range and can see Lone Peak and you know how the land beneath it is being transformed in a way that makes one think of the kind of resort pressure around Vail, what does it mean for the Madison Valley in years ahead?

Doris Fischer: My expectation is that the Jack Creek Road – long touted as a private road with minimal traffic so as to retain the wildness of Moonlight’s conservation lands plus the national wilderness areas to the north and south – will be opened for full-blown public use.

Pressures being applied to open the road from emergency service providers, Big Sky workers and suppliers, and Big Sky recreational customers are enormous. I worry that a Jack Creek Road, made public, will prompt unparalleled growth in Ennis and the Madison Valley beyond what is already happening. Were that to occur, we should expect to experience radical changes to the character of a one-of-a-kind rural community, the iconic river that runs through it, and the surrounding landscape which is steeped in history, couched in stunning scenery, blessed with a diversity of wild creatures, and filled with examples of how agriculture and recreation can co-exist.

TW: That possibility is horrifying for many to contemplate. But until destruction happens, it’s not inevitable and can be prevented. Roughly half of the Madison Valley’s open space is protected through conservation easements. But is planning is not pursued to protect the remaining viewsheds, the river corridor, wildlife migrations and water, what will the consequences be?

Doris Fischer: Further, extensive erosion of these priceless treasures, no question.

TW: In many counties, there is a deliberate attempt to evade the topic of zoning and it’s been going on for years, even by conservation organizations, based on the false assumption that landscapes are going to be protected if only there’s more hand-holding with landowners.

Doris Fischer: I don’t think conservationists and communities should be dancing around the topic. What are we waiting for? Zoning needs to be part of every conversation in talking about the tools available to accommodate some level of development and achieve conservation of what citizens value so highly. We should make it a topic of deliberate discussion so people can learn what it is and isn’t, what it can do and cannot do, within the sideboards of Montana state laws, which seem to be ever changing with respect to land us. In some ways, things are more permissive than what they used to be and in other respects much less enabling of local control. Both are problematic.

TW: Why is zoning important?

Doris Fischer: The case for zoning doesn’t require add ons to make it more palatable or a complicated bunch of regulations. I almost feel like the simpler we keep it the better so that people can understand it so there aren’t many surprises. I feel as though we’re already coming from a place, because of lack of guidelines or regulation that we’ve over-incentivized as it is and that creates a lot of people trying to exploit loopholes, or press for variances, which results in a lack of consistency. The strongest incentive related to zoning is the predictability it provides for what can and cannot be done in a given area. That gives solace to citizens, protects values and sends the signal to developers they can’t do whatever they want.

TW: How well do you think newcomers and long-time residents co-exist?

Doris Fischer: It is an uneasy relationship for sure, until someone takes the initiative to reach out and meet-and-greet. It reminds me of my grade school experience, when I suddenly found myself the newcomer in my class. One classmate showed courage and kindness by sitting down next to me in the school cafeteria my first day, and offering me some of her potato chips. Childlike though my example may be, I see little difference between that and the innate responsibility old-timers have to help their new neighbors feel welcomed. The responsibility on both “sides” is to listen to one another, and not presume to be the only ones with knowledge and expertise to share. That said, it still doesn’t mean difficult decisions don’t need to be made. It all depends on whether you want a valley that looks like part of the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies in a few decades or you are willing to chart a different future.

TW: You see great value in re-stitching social interconnections as they used to exist before digital technology. And dialogue that doesn’t happen in transactional ways involving business deals with one side trying to protect things that can’t be replaced and another aspiring to aggressively monetize them or gain a personal benefit.

Doris Fischer: In the Ruby Valley, our local watershed council used to sponsor an annual “Welcome to the Neighborhood” free barbecue. It was a highlight on the summer events calendar, and a favorite of newcomers and long-time residents. If the Madison Valley does not already do something similar, it may be an idea worth pondering and borrowing.

TW: I think one form of that is the annual Weed Committee shindig sponsored by the Madison Ranchlands Group. I thank you for your time. Before you go, let’s end on a lilt. What’s your favorite thing about being able to live in Montana?

Doris Fischer: In Montana I feel more a part of the Universe than anywhere else I’ve lived or visited. Many valleys in Greater Yellowstone give others the same feeling. They are worth protecting and it’s not too late, yet.

TW: You’ve said citizens concerned about the changes happening in their community want to be advocates.

Doris Fischer: I’ll give you an example. The town of Sheridan [Montana[ has recently established a planning and zoning board. And it is designed specifically to help residents learn about and look at zoning as a tool. That gives me hope.

ALSO READ:

Meet The Real Madison—And Why It’s Called ‘A Mini-American Serengeti’

Refusing To Surrender Wild Ground

Proposed Suce Creek Luxury Resort In Park County Is Just “Tip Of The Iceberg”

What’s Facing The Madison Valley? A Longtime Conservation Land Broker Weighs In

The Spillover Effects Of Big Sky’s Ravenous Appetite For More

New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife