by Todd Wilkinson

Try to recall your last memorable sighting not of wildlife in Greater Yellowstone but of people—here or any place else in the Lower 48—wearing wildlife; yes, wearing, as in we modern 21st-century humans adorning ourselves with coats, mittens and hats made from the pelts or feathers of wild public animals.

Perhaps you caught glimpse of a woman wrapped in her grandmother’s mink stole. (Reportedly, it takes between 50 and 80 mink to provide enough fur for a full-length coat). Or maybe your sighting involved a mountain man re-enactor donned awkwardly in a heavy bison cape. Or, possibly, you encountered a dandy from Wall Street on vacation in the West, walking off a private jet, his head covered in a ushanka comprising a stylish blend of Canadian or Russian wolverine fringed with rabbit hair.

This is not an inquiry freighted with snark. It’s intended to highlight something that ought to be obvious. For a long while in America it’s been neither common, nor prestigious nor fashionable to be seen in wild fur. Despite this reality, legislators in many rural states routinely devote an outsized amount of energy to protecting a pastime—trapping—that only a tiny fraction of citizens participate in, and whose contributions to local economies, livelihoods and culture is, within the big picture, insignificant at best.

I confess: I understand the individual allure of trapping. I had a trapline during a few teenage years growing up in Minnesota, catching mink, muskrat and raccoon and selling furs to buyers connected to international networks, part of a tradition on this continent that went back centuries. Even then, few people I knew made a living from trapping in the 1970s, and the prices fetched for wild fur today for most species are even less than they were 50 years ago.

“The classic view of trapping is one that derives from the romance of the mountain man era: rugged individuals braving the wilderness to make a living on beaver pelts and ermine,” Montana fur hunter Toby Walrath wrote in a story for Outdoor Life magazine in 2016. “The modern reality is significantly different, and it’s a major eye-opener at fur auctions: Most furs for sale at U.S. and foreign markets are not from wild animals. Rather, they are from domestic suppliers, owners of mink farms and other breeders of captive fur. And it’s this ‘ranched’ fur that is the backbone of the fur trade…”

Walrath quoted an expert who said that “wild furs are riding the coattails of ranch furs, no doubt about it. There is more ranched fur produced worldwide than wild fur, and by a wide margin.” Walrath then added this: “Unlike fur farms, the owners of which have the luxury of harvesting skins when they are peak value, wild fur-takers must work within seasonal constraints established by government agencies, and must suffer the vagaries of weather and geography. But when the prices paid for ranched mink go up, so do wild-fur prices, because wild fur complements ranched fur, especially on collars and cuffs. And it’s the unpredictable whims of the international fashion industry that really drive the fur business.”

“The classic view of trapping is one that derives from the romance of the mountain man era: rugged individuals braving the wilderness to make a living on beaver pelts and ermine. The modern reality is significantly different, and it’s a major eye-opener at auctions.”

—Toby Walrath writing in Outdoor Life magazine

In other words, decisions affecting the consumptive pressure placed on wildlife populations in Greater Yellowstone and elsewhere in the Lower 48 are made in distant cities like Milan and Paris, based upon unpredictable whims of urban effetes, with little regard or empathy given to ecological impacts caused by their decisions. This is exactly the same as it was when the Hudson Bay and American Fur companies (the latter headed by New York tycoon John Jacob Astor) emptied the West of species to feed a market of consumers in Europe who were either unaware or unconcerned about the impacts of choices they made.

I was reflecting on all of the above recently while standing in front of Helen Seay’s two-walled nature mural in downtown Jackson Wyoming. Seay’s artwork, comprising most of the wildlife species that inhabit Greater Yellowstone and set it apart in the Lower 48, is a visual feast. The installation is sponsored by the Jackson-based conservation organization, Wyoming Untrapped (WU), and is intended to celebrate the inspiring panorama of wildlife in Greater Yellowstone. WU’s mission is highlighting the intrinsic, often-overlooked value of living wildlife and educate the public about the impacts and perils of trapping affecting targeted and non-target species, including pets.

While the animal subjects portrayed on Seay’s open air “canvas” never show up in US Census Bureau statistics, they represent an important population demography just the same, a diversity of which that does not exist in most other states.

Consider one group of species in particular that is well represented in her tableau— a grouping of animals known as the “mustelids.”

Mustelids—more commonly referenced as members of “the weasel family”—are an impressive, distinctive lot. Count up the variety represented in Seay’s mosaic and try to find them all. On the larger end of their family tree are wolverines and otters (river and sea) while, on the smaller end, there are three species of weasels: the least, long-tailed, and short-tailed—also known as ermine or stoat whose fur changes from dark brown to white in winter.

In between are badgers, fisher, pine marten, mink and black-footed and domestic ferrets—each one a mustelid. Pound for pound, these meat and fish-eating carnivores are scrappy and tough, some capable of bringing down prey much bigger than themselves. Amazingly, ten different species inhabit Greater Yellowstone or nearby environs. See them in the photo gallery at bottom.

Venerated as icons, wolverines are the mascot of the University of Michigan, badgers for the University of Wisconsin, and otters for the University of California-Monterey. Worth noting before we proceed further: mustelids do not prey upon humans, nor are they considered a major threat to domestic livestock and pets. (Otters, as well as bald eagles and osprey, do occasionally feast upon trout stocked in private fish ponds installed on the estate grounds of often wealthy New West home owners but it raises the legitimate question of who is inviting conflict)?

All wildlife in the US, regardless of how it is classified, belongs to the public. Government agencies—state and federal— have an obligation, as part of the public trust doctrine, to manage species in the larger public interest and in ways that are moral, ethical and responsible. Trapping, snaring, sport shooting of fur-bearing species and killing them for fun are the only activities that serve as exceptions to the principal that terrestrial wild wildlife will neither be commodified nor treated as valueless.

For centuries, trapping was an extension of prevailing societal values because it delivered, one could argue, products of necessity because better alternatives were not available. After Europeans arrived on the North American continent and recognized how huge profits could be achieved by treating fur bearers as basically free commercially tradable commodities that could be extracted (like minerals, trees or crops), trapping fueled a lucrative consumer export market. Even today, the vast majority of wild fur reaped on this continent is exported, with one of the biggest importers being the Chinese, which is also actively engaged in the legal and illegal trade of animal parts for species like rhinos, elephant tusks, elk horns and carnivores for alleged medicinal purposes.

In the case of mustelids and other species, should living creatures inhabiting the forests and waters of the Northern Rockies be rendered mere trade goods to provide sartorial pleasure for people on the other side of the world?

During the 18th and 19th centuries, it didn’t take long for the plundering of fur bearers, driven by greed, to decimate the “natural resource.” Millions of animals were killed solely for their skins and their remains left to rot. With few exceptions, no human dines on fur bearers, certainly not on mustelids.

When commercial fur trapping started, and so-called mountain men and professional trappers were joined by indigenous trappers in supplying pelts, there really was no notion of ecological limits. Many wildlife populations, blindly approached as boundless, were exploited to near extinction.

All one needs to do is mention two species—bison and beaver—that are the most prominent on a long notorious list. One North American mustelid species, the sea mink, which resided in New England and eastern Canada was trapped to extinction.

No wild mustelid population needs to be “regulated” by humans or “lethally managed” in order to protect people, livestock, pets, and property or to enhance “ecosystem balance.”

The “mountain man era,” still venerated in the West as some kind of cultural and historic high-water mark, actually was short lived, lasting only a few decades, but it did leave behind a legacy, arguably one that shines a spotlight on the consequences of short-minded thinking.

Some species of mustelids are still recovering biologically after being “exhausted” near two centuries ago by trappers and, subsequently, they barely survived additional decades of significant threat when poisons were deployed to kill carnivorous wildlife—wolves, coyotes, bears and mountain lions— on behalf of the domestic livestock industry. Millions of non-target scavengers died eating carcasses laced with strychnine.

One of those nearly wiped out south of Canada was the largest mustelid, the wolverine. Today, scientists estimate there are around 300 wolverines—yes, just 300— in all of the Lower 48. Trapping wolverines is prohibited because they are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Still, wolverines remain vulnerable to being killed in traps and snares set for wolves, mountain lions and bears—practices that state legislatures in the Northern Rockies have authorized in recent years to be more widespread, including on lands near national parks.

Wolverines have huge home ranges. If just one male or female wolverine, part of a mated pair, were accidentally killed in a trap, it could result in reproduction ending in that entire area. Their persistence is also threatened by diminishing snowpacks due to climate change. Snowpack is crucial to foraging and successful wolverine pup rearing.

Another charismatic mustelid, river otters, were eliminated from many states by the early decades of the 20thcentury. They are re-colonizing reaches of rivers and lakes where they were once eliminated. In 2025, the Wyoming legislature passed a new law that removes otters from a state list of protected animals, reclassifying them as non-game animals.

Trapping of otters has been prohibited since 1953. The move in the Wyoming legislature was done ostensibly to give Wyoming Game and Fish more flexibility in “managing” otter populations and dealing with complaints from homeowners with stocked trout ponds. Game and Fish insists there is no plan to bring back otter trapping but many believe the reclassification is a first step to do exactly that. Moreover, it begs the question: why are otters labeled nuisances for eating captive trout put in fake ponds so that wealthy landowners can pretend they are casting for wild fish.

Yett another mustelid, the black-footed ferret, was once considered extinct but in the early 1980s, a tiny remnant group of ferrets was discovered in Greater Yellowstone near Meeteetse, Wyoming. Black-footed ferrets, which rely upon having access to healthy prairie-dog populations, their primary prey species, are the most endangered land mammal in North America and the only mustelid uniquely native to this continent. Wyoming has been a leader in ferret research.

After the only known wild survivors were brought into captive breeding programs, some ferrets have been reintroduced to nearly three dozen sites deemed suitable in Wyoming, South Dakota, Montana, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Kansas, New Mexico, Canada and New Mexico. Classified as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, trapping of ferrets is prohibited.

Meanwhile, challenges face other mustelids for which there are trapping seasons in Northern Rockies states. Fisher populations, including those in the Northern Rockies, continue to face challenges from habitat loss and fragmentation, with Pacific fishers on the West Coast often mentioned as candidates for federal protection. While they can be trapped in Montana and, they are protected in Wyoming and Idaho. The status of marten, another mustelid, parallels that of fishers in some states and scientists say it’s important that populations be monitored. Marten can be trapped in Wyoming, Montana, and Idah.

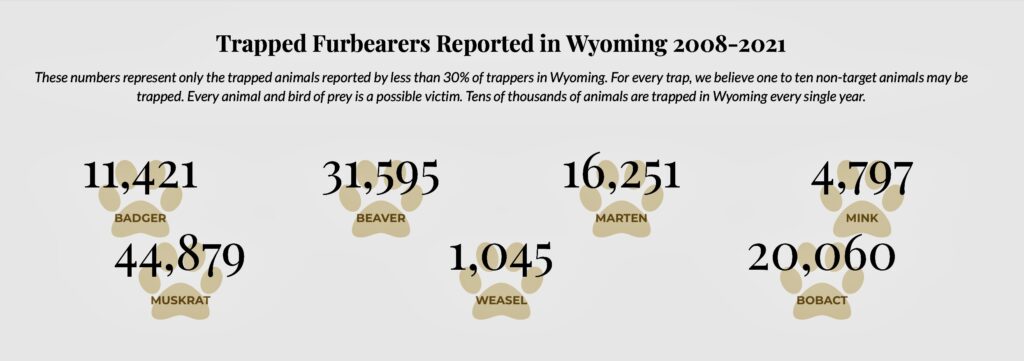

According to a special analysis from Wyoming Untrapped, reported numbers of animals taken by traps and snares each year accounts for around 30 percent of likely totals, and that for every trap set on the landscape there is the potential for between one and 10 other “non-target” animals to be caught, including birds of prey, family pets and imperiled species. Besides Wyoming Untrapped, another organization that separates fact from fiction about mustelids is Genuine Mustelids.

The reported numbers of animals taken by traps and snares each year accounts for around 30 percent of likely totals, and that for every trap set on the landscape there is the potential for between one and 10 other “non-target” animals to be caught, including birds of prey, family pets and imperiled species.

—Info from report by Wyoming Untrapped

At present, severe budget cuts being mandated by the Trump Administration threaten to decimate not only the ranks of already-limited field researchers but the resources they need to conduct surveys that are time intensive and difficult. Some species of mustelids exist at incredibly low population densities and along with slow reproduction rates leaves them vulnerable to suffering declines without scientists immediately realizing it’s happening.

Whether you believe trapping animals for their fur is cruel, inhumane and has no place in our modern world, or that it’s a cultural artifact worth preserving, is up to you. Readers will draw their own conclusions about the merits or depravities of trapping and snaring.

The Montana Trappers Association insists that “anti-trapping is anti-wildlife” and offers a fact sheet about trapping. To further make its argument, the association cites these reasons which are highlighted on a site, “Truth About Fur” created by the Fur Institute of Canada (which, next to Russia, is the largest producer of wild fur in the world). Trapping advocacy groups assert that trapping is a net-positive activity. It helps, they say, “regulate populations” of animals and “keep them in balance”; it can be used as a tool to protect imperiled or game species threatened by predators; it can be employed to protect livestock, property and human health; and data gathered by trappers can advance wildlife research, it says. In addition, trappers say their activities provide food for the table, generate income, and supports land-based cultures. “Truth About Fur is intended to give a voice to the men and women who carry on this unique artisanal tradition, working as fur farmers, trappers, traders, processors, designers, craftspeople, and retailers,” the site says. Compelling counter-arguments are that commercial and recreational trapping is cruel, the trade in wild fur is an anachronism.

In this, the third decade of our new millennium, it’s been a long time since wearing “wild fur” was essential. In Outdoor Life, fur hunter Walrath shared this observation: “This process of pelt collection, processing, and sale is repeated thousands of times a year in rural towns around the continent by individuals just like some—small-time trappers who enjoy the challenge of trapping and the opportunity to sell a few pelts to buy more traps and pay for a tank or two of gas to fuel our next check of the trapline. Together, we are the ragtag supply chain for an international retail fur trade that exceeds $14 billion annually.”

Reasonably, we might wonder: Should our public wildlife be exploited to serve “a ragtag supply chain for an international retail fur trade?” This is not an indictment of trapping; rather a presentation of evidential facts that, unfortunately, many state legislators pushing to expand trapping rights often avoid confronting. No wild mustelid population needs to be “regulated” by humans or “lethally managed” in order to protect people, livestock, pets, or property or to enhance “ecosystem balance.” There also is no compelling commercial reasons, as noted above, that trapping wild mustelids for their fur represents an essential economic engine. Still, some have tried to make political hay, pushing to have trapping recognized as a fundamental right and expression of liberty embodied in proposed amendments to state constitutions.

If the rational is merely to generate money for more traps or pay for a few tanks of gas, then what is the higher virtuous purpose of trapping mustelids and other animals? Is it something so important that it needs special protection within a state constitution. Really? Is it more important than, say, making access to quality health care a fundamental human right?

Contrary to another myth, it’s not environmentalists or animal rights activists who rendered the US consumer market for fur antiquated, but rather private commercial fur farming, outdoor gear companies and the buying preferences of consumers. Technology made the clothing we wear in the great outdoors, that exists as alternatives to fur, cheaper, lighter, warmer and hipper. Even trappers don’t often wear fur to protect themselves from the elements; most are likely buying layered outerwear made of nylon, polyester and other synthetic materials.

Contrary to another myth, it’s not environmentalists or animal rights activists who rendered the US consumer market for fur antiquated, but rather a glut of product owed to private commercial fur farming and outdoor gear companies. Technology made the clothing we wear in the great outdoors, that exists as alternatives to fur, cheaper, lighter, warmer and hipper. Even trappers don’t often wear fur to protect themselves from the elements; most are likely buying layered outerwear made of nylon, polyester and other synthetic materials.

Wyoming Untrapped and Seay hope those visiting her mural will take a few moments to reflect as they try to identify all of our region’s amazing mustelids. For readers here, a few more questions worth pondering:

What is the real value of having a full complement of native free-ranging public wildlife of the kind that exists in Greater Yellowstone and nowhere else in the Lower 48?

What is society’s obligation to safeguard species facing perpetual threats to their survival, many that are human-caused?

How do we better assess the intrinsic worth of another being beyond its liquidation value in a financial market?

Does wearing dead animals enhance our appreciation and respect for living ones?

The point of considering the above? These are questions that once you let them into your conscience and brain, you cannot unthink.

This story is part of an ongoing series titled Wild Journeys inspired by Helen Seay’s two-wall outside mural in downtown Jackson, Wyoming and sponsored by Wyoming Untrapped. Other stories that have appeared so far:

Mustelids of the Rockies