by Todd Wilkinson

To visitors arriving in Jackson Hole to ski and snowmobile every winter, the sight of thousands of elk massed together on the National Elk Refuge just north of the town of Jackson is spectacular indeed. It gives the impression that this is the very epitome of wildlife conservation at work— the same as gazing upon the Tetons delivers a glimpse of pure mountain majesty.

But any superficial assumptions drawn by those with untrained eyes and holding little knowledge of human and natural history in the valley could result in a misleading conclusion. Far from being wapiti nirvana, the 24,700-acre Elk Refuge is the product of what happens when vital ungulate migration routes become blocked by human development.

In the early years of the 20th century, as Jackson Hole was becoming populated with hardy year-round settlers, structures and human activity impeded the ability of elk to migrate southward out of the valley in autumn—the same as mule deer and pronghorn in Grand Teton National Park do today—bound for lower elevations and easier living in the Upper Green River Valley and Red Desert.

Jackson Hole, nearby Yellowstone and mountain areas of the current Bridger-Teton and Shoshone national forests were summer destinations but Jackson Hole when the snow started to fly, according to one comprehensive analysis by Christina Cromley a research associate with the Jackson-based Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, primarily served as a pass-through zone. That’s because deep snows buried natural forage and limited the sustainability of large elk numbers. When development blocked the ability of segments of the elk herd that would ordinary migrate south, and then the corridor was severed and migration was lost, elk became stranded during winter in the valley and thousands died.

This necessitated hasty establishment of the National Elk Refuge in 1912 along with its artificial feeding program that continues to this day. The unnatural bunching up of thousands of wapiti may be a visual marvel but it has produced a number of serious concerns about the spread of epizootic diseases such as deadly Chronic Wasting Disease, brucellosis, bovine tuberculosis and others. A great reference is the National Elk Refuge’s former senior range biologist Bruce Smith, who wrote the award-winning Where Elk Roam: Conservation and Biopolitics of Our National Elk Herd.

In many ways, the situation is the mother of all cautionary tales in Greater Yellowstone for what can happen when a major migratory lifeline is severely impaired by sprawl and related factors. And, besides inviting intriguing speculation on whether migratory behavior could ever be re-established/nurtured in elk to facilitate movement to southern winter range, it also serves as a warning for what could happen to mule deer and antelope navigating the Path of the Pronghorn if their migratory routes were blocked or constricted.

° ° ° °

Dr. Matthew Kauffman of the USGS leads the Wyoming Migration Initiative at the University of Wyoming. He recently was honored with the prestigious Aldo Leopold Award given by the American Society of Mammalogists for his work—and that of colleagues—in advancing understanding of how wild ungulates move across the landscapes of Greater Yellowstone.

In the summer of 2023 at an international conference on wildlife migrations held at Jackson Lake Lodge (which Kauffman co-organized), he said the following to me as we chatted amid a room full of wildlife migration experts from around the world. In our region, private land sprawl and subdivisions, hands down, he said, are the most consequential and growing threats to protecting Greater Yellowstone’s globally famous wildlife migration corridors. Energy development, fences and highway collisions take their toll, but sprawl is different because it’s permanent.

Other conservation biologists whom I’ve interviewed share that view. Residential rural subdivisions, they say, are as devastating to migrating elk, mule deer and pronghorn as full-field oil and gas development. Sprawl that spreads into forested terrain is as disruptive to wild species living there as clearcut logging is. Homes that line river corridors and operate on individual septic systems are potentially as menacing to wildlife using riparian areas and water quality flowing through blue-ribbon trout streams as any hardrock mine is. A meadow covered by ranchettes and condos on winter range exacts far more negative impacts on roaming wildlife than any pastureland peppered with domestic livestock and fences.

But, there is a difference: Oil and gas fields, clearcuts and mines often occur on public land and there are laws in place to deal with their environmental impacts, either to prevent or minimize them. Eventually, one day, oil and gas wells will go away when the fossil fuels dry up, forests can grow back and land disturbed by mines can be healed and rehabilitated.

Regarding livestock grazing, there are impacts, including predator control, but ranchers provide habitat for wildlife on their private lands and many don’t often complain, seeing it as a tradeoff for running cattle on public lands at subsidized rates.

Fences, a scourge to wildlife, can be removed or converted to wildlife friendly versions. Wildlife overpasses and underpasses can be constructed to facilitate safer animal movement and markedly minimize collisions that take human and animal lives and cause millions in medical bills and property damage. Outdoor recreation on public land, which at certain levels displaces wildlife, can be halted or adjusted to minimize intrusion.

These are activities that can be readily addressed. But the impact of private land subdivisions is forever, Kauffman and others note. Sprawl never goes away and its impacts deepen over time. It can sever a wildlife corridor that has been on the landscape for 10,000 years. It produces a multitude of negative spillover effects that impact a vastly larger volume of land than the actual physical footprint—including, in some cases, impairing the ecological function of adjacent public land. Doing things such as installing bear-proof trash bins in local communities is laudable, but they only delay conflict if they’re placed in a subdivision that has usurped grizzlies and other wildlife of habitat. Trash-habituated bears are a symptom; whereas sprawl is the pervasive problem.

Residential rural subdivisions are as devastating to migrating elk, mule deer and pronghorn as full-field oil and gas development. Sprawl that spreads into forested terrain is as disruptive to wild species living there as clearcut logging is. Homes that line river corridors and operate on individual septic systems are potentially as menacing to water quality flowing through blue-ribbon trout streams as any hardrock mine is. A meadow covered by ranchettes and condos exacts far more negative impacts on roaming wildlife than any pastureland peppered with domestic livestock and fences.

Retired private land conservationist Dennis Glick, featured in an earlier piece at Yellowstonian, asks rhetorically, “When was the last time you ever read in the newspaper of a subdivision disappearing after it was built, or before it was built being subjected to intensive analysis through an Environmental Impact Statement to gauge its impacts on wildlife—as proposed public land developments are required to undergo? You know what the answer is: almost never.”

By sheer coincidence, another person asking the same questions is Leon Kolankiewicz. He was working in Central America around the same time Glick began his career more than 40 years ago, doing similar conservation work, after both, separately, had gone there as young Peace Corps volunteers.

Kolankiewicz married a Honduran and together they have two now grown children who live in the US. For the last three decades, he has specialized in assessing the impacts of proposed human developments on nature. (As a side note, I met several colleagues of Glick and Kolankiewicz in 1992 when I attended the World Parks Congress in Caracas, Venezuela. I went there with Glick and resource/community conservation economist Ray Rasker. During that trip, we spent a fair amount of time in the company of William Newmark, a globally-renowned expert on the impacts of how development and human pressures happening around the perimeter of national parks can severely impair their biological health).

Kolankiewicz understands better than most why sprawl is an existential threat to a bioregion like Greater Yellowstone, often referenced as “one of the most intact ecosystems in the temperate zones of the Earth”—and whose rare celebrated wildlife populations depend on it remaining that way. He is lead author in a new scientific analysis, Greater Yellowstone—An Ecosystem At Risk: Unending Population Growth and Development Threaten the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, published by NumbersUSA on the impacts of sprawl on Greater Yellowstone.

Kolankiewicz says it’s curious that dozens of conservation organizations are arrayed in scrutinizing and fighting certain activities, such as a proposed copper mine in the headwaters of the Smith River in Montana, but few of those same groups are subjecting Big Sky or private land development proposals in other corners of the ecosystem to equal levels of intense scrutiny when they, over time, are an equal and over time more prolific threat.

Glick and Kolankiewicz in separate conversations arrived at the same observation and it is this: if environmental groups, federal agencies and wildlife-loving citizens in Greater Yellowstone were aware of that an existing and rapidly expanding threat stood to permanently impair the ecological function of fully one-fourth of the ecosystem’s public lands, they would be vocal, aggressive and fundraise in fighting it.

And this is, in fact, what’s happening, on a massive scale, right now on private land with sprawl, they say. Regarding the reason why development decisions on private land in Greater Yellowstone are not subjected to the same kind of vigorous scrutiny as that which natural resource extraction faces on public land, this is the ultimate deliberate blind spot.

Glick and Kolankiewicz in separate conversations arrived at the same observation and it is this: if environmental groups, federal agencies and wildlife-loving citizens in Greater Yellowstone were aware that an existing and rapidly-expanding threat stood to permanently impair the ecological function of fully one-fourth of the ecosystem’s public lands, they would be vocal, aggressive and fundraise in fighting it. And this is, in fact, what’s happening, on a massive scale, right now on private land with sprawl.

It doesn’t happen because it’s not required or not enforced by state agencies, counties and towns, and with only rare exception, are subdivisions subjected to scrutiny with important ecological considerations in mind. There are not many examples in Greater Yellowstone or the Northern Rockies, Glick says, “where the cumulative impacts of multiple subdivisions and the consequences of ‘leapfrog development’ on wildlife and water have been considered by counties and then held in check.”

“It’s the gaping hole in how we think about protecting ecosystems, the elephant in the room that’s right in front of everyone but conservationists, who normally position themselves as watchdogs, don’t like to talk about,” Kolankiewicz says. “Private land development is just not subjected to the same depth of opposition, habitat protection standards and evaluations that happen on federal and some state public land.” Plus, few realize, Glick adds, that the ecological values present on many sweeps of private land rival, if not, surpass, those on nearby public lands.

Wildlife don’t recognize any difference in whether land falls under one jurisdiction or another. “Destruction of habitat is destruction whether it’s occurring on a national forest or private land. The consequences are the same,” Glick says. “If the goal is saving wildlife and connectivity for animals that need to move and water quality in these vaunted rivers you have in Greater Yellowstone, that disconnection needs to be addressed; what’s happening now needs change.”

When Kolankiewicz was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia, his thesis advisor and mentor was Dr. William E. Rees, best known for co-developing the ecological footprint concept with his UBC doctoral candidate Dr. Mathis Wackernagel. Rees and Wackernagel co-authored the 1996 book Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth, which is available in nine languages. The ecological footprint concept has become a household phrase around the world, and the term “footprint” is now synonymous with human behavior and its impact on the planet.

“The impacts are at first subtle and incremental, but they are insidious and over time they can become significant. At some point citizens wake up and they wonder, ‘What the hell happened to this place? I never knew that it would be this bad. If I had only known, I might have spoken up.'”

—Leon Kolankiewicz

The US National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is called “the Magna Carta of environmental laws” in the world. One of the essential tenets of NEPA, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1970, is it guarantees that citizens have a voice in being able to comment on proposed natural resource extraction activities and other potentially damaging activities on public land.

As a conservation biologist with a special expertise in writing and managing NEPA reviews of activities proposed for public lands deemed significant by a variety of federal land management agencies, Kolankiewicz has been involved with completing over 100 Environmental Impact Statements and Environmental Assessments. He has helped the US Fish and Wildlife Service complete more than 40 management plans for different national wildlife refuges. For NumbersUSA, he also has authored 16 studies on the impacts of sprawl in differing US states and the Chesapeake Bay bioregion. He unveiled the Greater Yellowstone sprawl study last September at the Yellowstone Biennial Science Conference, ironically held at Big Sky, often held up as the emblem of sprawl run amok in the Northern Rockies.

Because private land subdivision proposals are presented and greenlighted piecemeal, the public often is anaware of what their cumulative effects will be, Kolankiewicz says. “The impacts are at first subtle and incremental, but they are insidious and over time they can become significant. At some point citizens wake up and they wonder, ‘What the hell happened to this place? I never knew that it would be this bad. If I had only known, I might have spoken up,'” Kolankiewicz explains. “How short our memories are. We aren’t aware of what’s being lost unless there are baseline data to measure against. People forget what it was like 10, 20, 30 years ago and young people have no perspective on what the trendlines mean.”

In a new book of essays, A Watershed Moment: The American West in an Age of Limits by multiple authors, Kauffman co-wrote a chapter on Wyoming’s wildlife migrations with science writer Emily Reed. In dramatic fashion they give readers a front-row seat to what migrating mule deer and pronghorn face on annual journeys in the southern half of Greater Yellowstone. Touting progress made in mapping migration corridors and private-public partnerships forming to keep them intact, they pull no punches in noting human development pressure.

“It’s clear that some of Wyoming’s migratory routes are still intact today because of the open space, but we know that they are still vulnerable, especially in today’s modern world. Similar to the Western ‘boomtowns’ brought about by oil and gas, there are now ‘zoom towns,’ where remote workers are moving to Western gateway communities and building houses, some of which are in crucial winter range areas for wildlife. Green energy initiatives have led to solar panels and wind turbines being assembled across the prairie, sometimes within migration corridors or winter ranges of the state’s abundant ungulate herds. The reality is that without adequate protections for habitat, any type of development poses a threat to migrating wildlife populations,” they note, and then add:

“Conserving wildlife while providing for the needs of a growing human population is possible—it is not an either-or proposition. But it will require more cooperation. Untangling how we can make these compromises in modern society across multiple scales will require us to prioritize the importance of understanding how to communicate better about what the science is telling us and to integrate that into communities for their knowledge and planning.”

For its new sprawl study, NumbersUSA asked me to write a foreword about trendines in development pressure in Greater Yellowstone that I’ve witnessed over the last 40 years. Kolankiewicz and I, speaking as researcher and journalist, recently joined Jack Humphrey on his ReWildingEarth podcast in a segment titled “How to Save Greater Yellowstone from Runaway Sprawl.”

Greater Yellowstone is comprised of 20 counties. All have land management plans, per state laws, but few have a cohesive strategy to deal with sprawl. In fact, many elected officials serving as county commissioners refuse to consider implementing planning and enforceable zoning that would safeguard open space, wildlife habitat, safeguard ag land and address growing water concerns.

Dr. Arthur Middleton, a scientific colleague of Kauffman’s who also studies migrations, recently penned an op-ed in The New York Times and he said Greater Yellowstone has about five years to safeguard corridors in the face of development pressure that is squeezing them shut. Migratory herds, he wrote, can tolerate some disturbance but they begin to avoid areas where more than 1 percent to 3 percent of the land has been developed.

“These pressures require an all-hands-on-deck campaign to protect habitat on private lands and ensure that wildlife can roam freely. Any such effort will need the support of communities, states and hundreds of landowners — so it must be locally rooted and highly collaborative. It also has to be flexible, offering financial incentives to help keep working ranches intact while appealing to the better angels of the high-net-worth individuals who have been moving in.”

Middleton noted that the “primary tools available to protect private lands in the ecosystem are county zoning regulations and conservation easements. Many counties have imposed limits on rural housing density, but expanding such zoning restrictions may be unrealistic in this largely politically conservative region. County officials, particularly in agricultural communities, have legitimate concerns that limits on subdivisions can hurt families that are land rich but cash poor.” Given resistance to zoning, the only tool available is conservation easements but the funding capacity of land trusts cannot keep up with demand.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Sisson, a Park County resident who for years oversaw the conservation organization, ConservAmerica, recently served under the first Trump administration as a commissioner on the International Joint Commission addressing US/Canada border issues. As a citizen conservationist, Sisson is concerned about Lone Mountain Land Company’s presence in the Shields Valley and it bringing the same kind of mindset to monetizing real estate to its new holding in the Shields, Crazy Mountain Ranch, that it aggressively applied to the Yellowstone Club in Big Sky. At present there are growing concerns in the Shields about sprawl impairing wildlife habitat and setting off concerns about water.

“We have plenty of large land owners in the Shields who do a good job in conserving open space,” he says. “The danger is as development encroaches, it makes property values too high for sustaining traditional ranching or changes the ‘lifestyle’ such that landowners sell out to go find the next peaceful valley, leaving the Shields Valley to profiteers.”

____________________________________________________________________________________________

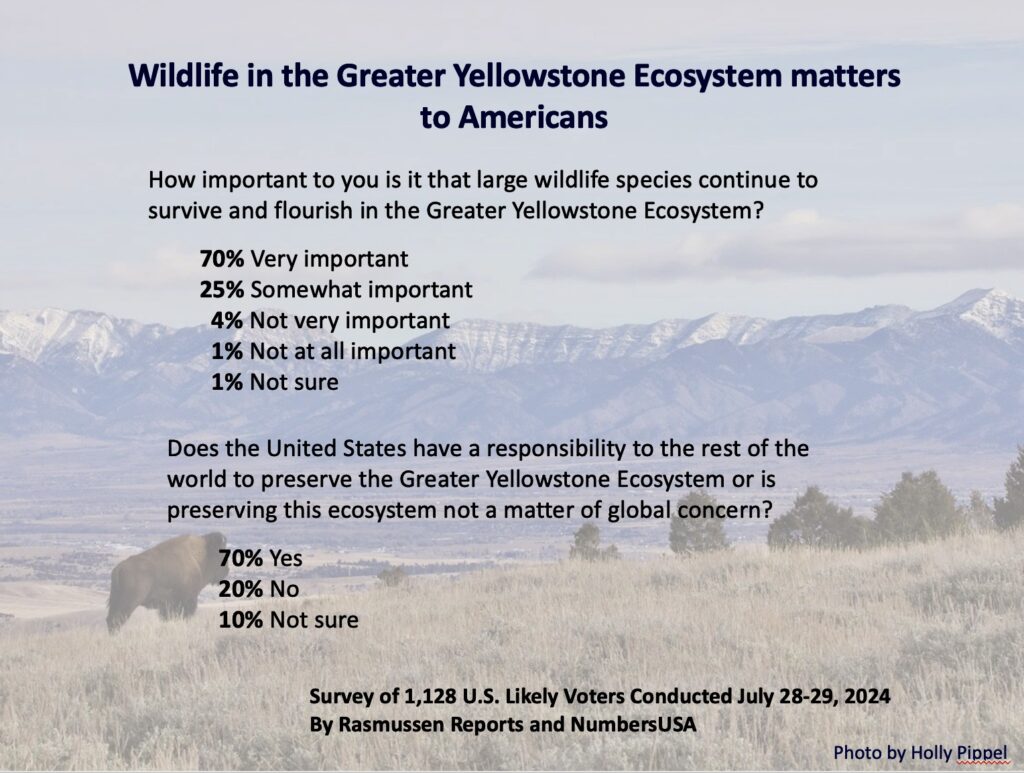

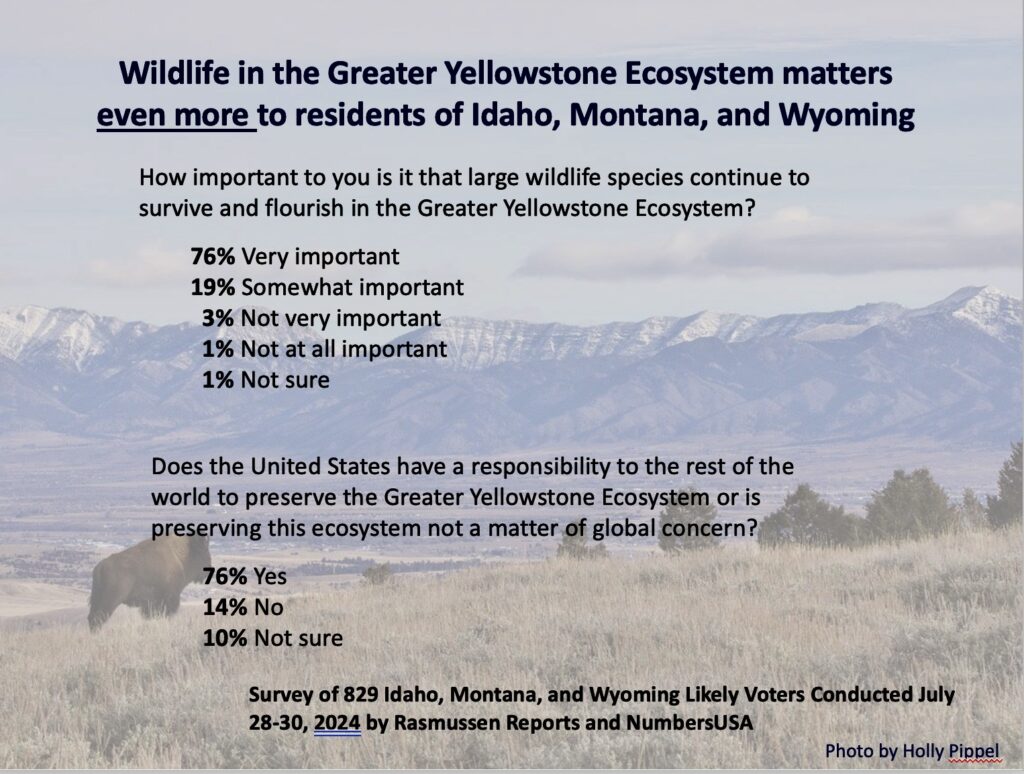

Glick wants to keep ranchers and farmers on the land but it’s anti-government, anti-planning and zoning zealotry that is accelerating negative change. Conservation organizations need to be more vocal and active in their advocacy for wildlife. Ultimately, he says, the public needs to decide is perpetuating Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife diversity matters. In more than half a dozen public polls and surveys he’s seen, wildlife protection is overwhelmingly supported but it’s not registering with the people being elected at the local level.

“Often, we hear the refrain from conservation groups that ‘Oh, we can’t mention the word ‘zoning’ because it might make property owners mad.’ Well, does that mean they [a few property owners] get to decide the fate of our wildlife and the health of our rivers?” Glick asks. “People forget that when Yellowstone was created as a national park in 1872, and the boundaries of Grand Teton were expanded, there were some angry local property owners who thought those were bad ideas. The truth is that many property owners are selling to developers who, in the absence of zoning, are doing whatever they want, no matter what the consequences are for wildlife. We’re seeing some really bad subdivisions and there will be a lot more. If we lose the health of our public wildlife there are going to be a lot of very mad and very sad citizens.”

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, he said, desperately needs a group to step up and launch campaign to conserve critical private lands but no such leadership presently exists. “Most groups have become conflict averse, or, at best, development is being scrutinized haphazardly and piecemeal, which isn’t effective,” Glick said. “Obviously, if the goal is preventing the de-wilding of wildlife in the years ahead, then no one can dispute that the current so-called strategy of ‘conservation lite’ is failing.”

Four decades ago, Kolankiewicz did field work on wild salmon populations in Alaska. “I was not exactly dismissive of the Yellowstone ecosystem and thought of it in terms of being a wonderful place but Yellowstone Park felt overrun. I thought that by being in the Far North I was in wilder more spectacular places with bigger mountains and wilder wilderness, but doing this sprawl study, seeing what’s still here in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, what’s been brought back despite earlier land abuse, it’s opened my eyes. This is rightfully the cradle of American wildlife conservation. It still has these vestiges of wildness but there are serious problems ahead if helter-skelter development continues.”

Compared to the other dozen sprawl studies Kolankiewicz has co-authored and comprehensive EISes and environmental assessments completed for public lands and waterways in other parts of the Lower 48, he is puzzled by the fragmentation in thinking that is another part of the problem.

“I’m a great believer in a sense of place, the biological and geographic and cultural attributes that come together to make it unique. I have traveled across North America, visiting every US state and every Canadian province and worked throughout Central America. There are spectacular settings anywhere you go, but the GYE is distinctive and unique,” he says. “The wildlife populations give it that. The notion of it being called the American Serengeti with all of its species is not a cliché. I feel very connected to it but it will only be saved if humans are willing to embrace one virtue: limiting how much they take from nature.”

Around the world, civilizations and great societies have risen and fallen since antiquity, but one of the few places left on earth that has never lost its native diversity, for thousands of years, is Greater Yellowstone. “Wildness is still real here,” Kolankiewicz says. “But will it last? What a shame it is that we even have to ask.”

BELOW: Two datapoints from a recent Rasmussen poll on attitudes of Americans and residents of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho on the value of wildlife in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

Some other stories in Yellowstonian’s ongoing series of stories about issues related to sprawl

What Happens When Greater Yellowstone’s Conservation Movement Goes MIA On Sprawl?

New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife

Wild Odysseys: Greater Yellowstone Migrations Hold An American Ecosystem Together

What’s Facing The Madison Valley? A Longtime Conservation Land Broker Weighs In

The Spillover Effects Of Big Sky’s Ravenous Appetite For More

On The Front Doorstep To Yellowstone, A Montana County Wrestles With How To Confront Change

What’s Facing The Madison Valley? A Longtime Conservation Land Broker Weighs In

Refusing To Surrender Wild Ground

Proposed Suce Creek Luxury Resort In Park County Is Just “Tip Of The Iceberg”