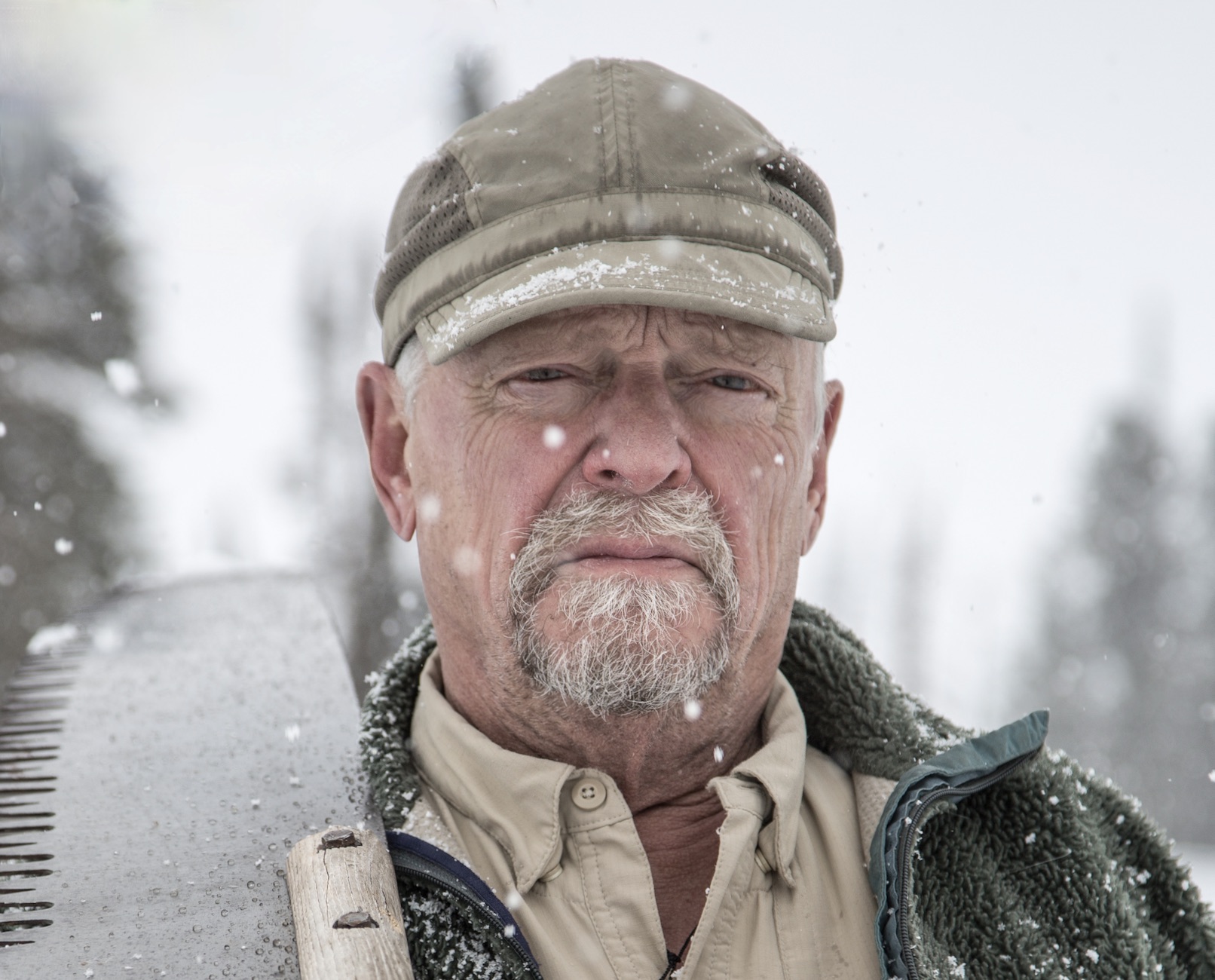

EDITOR’S NOTE: Across the span of living a half century in the middle of Yellowstone, Steven Fuller has witnessed innumerable examples of transition—season to season, liquid and even steamy water becoming solid, and a landscape frenetic with human activity during warm months turning markedly solitary and spatially remote. For Fuller, the arrival of Winter Solstice has signaled another kind of transition, this an inverted one. While the hours of daylight will slowly increase in the months to come, solstice has typically marked the start of Yellowstone plunging into the grip of a deep freeze. Well, that hasn’t been the case so far in his final season as winterkeeper. Below are a few Fullerian reflections as we enter 2025. —Todd Wilkinson

Words and Photographs by Steven Fuller

On nights like these, seen in any season from my house, there are no lights as far as I can see, which has long pleased me. But after November 1 when Yellowstone National Park is closed and the highways empty and the nights grow longer and existentially darker there is a disquietude I’ve felt each autumn for years.

Perhaps it is a sub recollection still carried within me of my northern ancestors whose dread I have not consciously shared here in Yellowstone. The Winter Solstice had long been one of many touchstones’ in our pagan ancestors reckoning of who and where they were in the cosmos. Currently it is calculated by those who keep track that we have been preceded by about 117 billion hominoid souls, the vast majority of whom were aware and celebrated the cyclical patterns overhead.

Early on, they kept their eyes and minds on the sky rather than immersed, as we are, in chimeras on our screens. Most of us today are ignorant of the natural surroundings that they understood so well. The ancient mojo of moving into winter has recently been reincarnated as a pagan holiday of unholy consumerism.

Or if you a devotee of the current scientific paradigm @ NOAA, you might receive this, as I did: “The Astronomical Winter Solstice occurred at Canyon Village in Yellowstone National Park 44.7338° N, 110.4899° W on December 21, at 2:20 AM.” The accompanying analytical numerical explications, graphs, images, and spreadsheets of the phenomena are fascinatingly abstruse and enlightening.

The Winter Solstice, December 21, was the longest night of the shortest day of the year. The arc of the sun that has shrunken for months can be supposed to stand still at the peripetela moment of the solstice, when it reverses its path so it daily grows higher and wider in its’ apparent arc. Then it reverses again at the Summer Solstice six months later. Simple and profound.

For countless millennia my ancestors in our cold dark north have marked and celebrated the return of the light on this dawn day though with some irony it is also the first day of the winter that follows. Perhaps their take was in keeping with the song “Accentuate the Positive.” Since the event is at the ambiguous cusp between light and dark I’ve some mixed feelings to share about the solstice.

And too, my long-established affection for winter as each post winter solstice day grows longer Is a harbinger of the approach of the opening of the summer touristseason and the startling urbanization of Yellowstone as millions crowd this island fragment of the natural world.

On the other hand I’ve enjoyed my longest night of sleep of the year when I need not be up for sunrise, (never is one to be missed), until quite late in the morning. Which is quite contrary to the June sunrise on the opposite side of the calendar. Traditionally, before electric lights and laptops the peoples of the north slept through much of the winter like many of my wild hibernal plant and critter neighbors.

And, our second daughter, Skye Canyon, a blessing born nearby on December 23, was perhaps persuaded to enter this world by the previous two days of waxing post solstice light.

Predominately I have delighted in Yellowstone winters since I landed here in 1973, especially in the weeks of December when the long cold nights sow the seeds of a cornucopia of spectacular frost crystals, light catchers and reflectors of many varieties.

Born of hot springs and geysers clouds of super cooled water droplets flash to a solid the instant they contact an aerial particle of soot, dust, or pollen which act as a seed on which frost crystals accumulate until their weight drags the mote to earth cleansing the atmosphere to an unprecedented seasonal clarity.

So at night the brilliant flicker of the stars is matched by the sparkle of “diamond dust” in the morning. When illuminated at sunrise the myriad of floating crystalline mirrors brings to light sun pillars, glories, and halloes that dazzle a receptive mind, be there one present.

And companies of pine trees that line the edges of geyser basins immersed in clouds of super cooled water vapor become ‘ghost trees” that accumulate accreted tons of frost encrustations in the course of the early winter.

Mundane buffalo tracks deeply pressed into impressible clay and earlier filled with snow melt water are frozen into a trackway of ichnite ice crystal filled geodes.

For these and many similar curiosities I esteem the short days that preserve and the long nights that nourish the ephemeral evanescent crystalline gardens of Yellowstone’s geyser basins. The extraordinary glory is short lived…snuffed, demolished, deconstructed, sublimated by the first warm days, usually shortly after the New Year, when “ghost trees” shed their loads and crystalline ostrich plumes shrink on a sunny afternoon and sublimate back into the ether.

This brief spell of virgin crystalline glory will not be seen again until next year’s Winter Solstice, which prompts a brief specter to flit across my mind. The smoky bite of a sip from a steaming cup of Lapsang Souchong melds with the augury of that knowing.

That Winter Solstice is a transition I will not witness in Yellowstone.