by Yellowstonian

Kaye Counts, Marina Smith and Samantha Arbogast have never thought of themselves as hell raisers. But somometimes there is a flashpoint. It hovers and becomes a test of community resolve with the potential to galvanize; a light of recognition that provides illumination and then sparks an opportunity for citizens to engage in common reflection. Often, when it involves land management matters, it surrounds a question: are we paying attention to what’s happening in the landscape around us, beyond our own bubbles, in those precious shared spaces of rural countryside that help remind us why we are here?

In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem today, there’s an ongoing meteor shower of flashpoints, involving everything from proposed gravel pits, luxury resorts and new subdivisions to concert venues, holistic retreats and what some have described as real estate plays masquerading as affordable housing.

In the rural southern end of Montana’s Madison Valley, a flashpoint for Counts, Smith, Arbogast and their neighbors arrived in December 2022 with a proposal to build, of all, things, not a subdivision of trophy homes and condos, but a 150-slot RV park. As you will read in the interview below with the three founders of a grassroot group, Preserve Raynolds Pass, the development provided a focal point for hundreds of residents who had a difficult time trying to describe unwanted change that had begun accelerating just prior to, and during, the Covid pandemic. It brought a wave of new property buyers and visitors to the Northern Rockies, many who had never lived in rural settings or ever considered the needs of wildlife.

Of the proposed Miles Creek RV Park south of the closest “town” of Cameron, which is barely a block long, these three advocates explained on their website, “We are not opposed to RV Parks and understand that change has entered Madison County’s door, but this application intended to place a high-density resort in the narrowest part of the migration corridor for elk and pronghorn in the Madison Valley.” Consulting scientists and independent planners added that once developments like this establish a precedent, more tend to follow rapidly. Irreversible cumulative effects can begin to register long before they become visible to humans driving down the highway.

After a long battle, the full Madison County Commission overruled a recommendation from the county planning board to approve the RV park with conditions, but the commission instead denied the application.

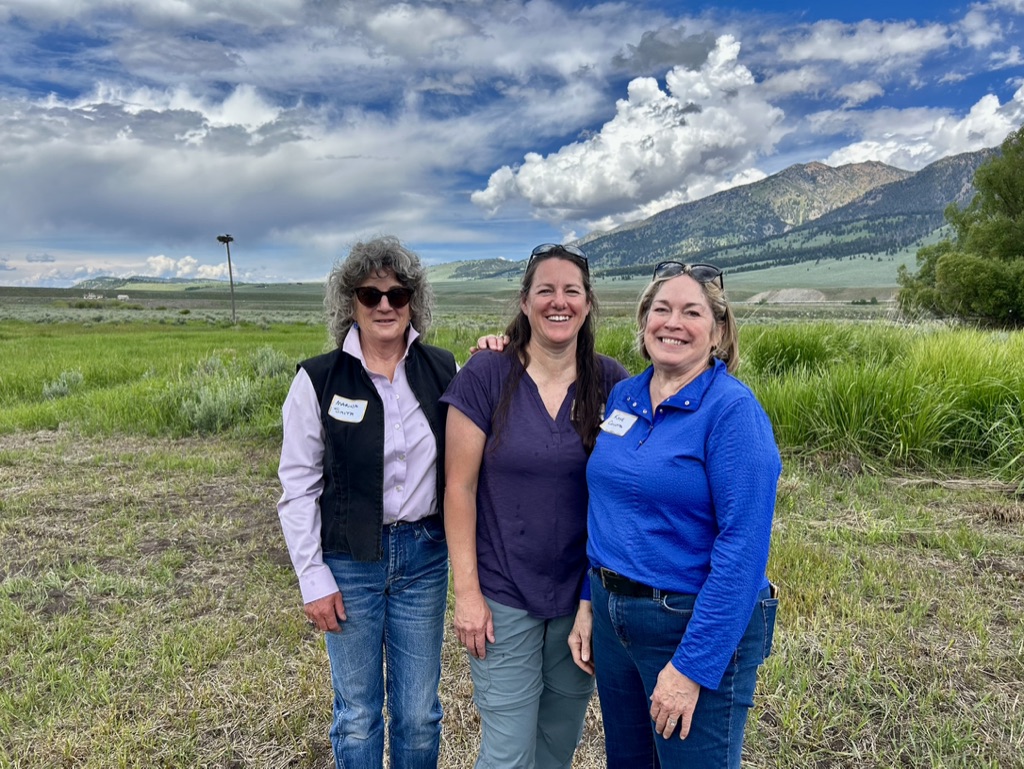

Preserve Raynolds Pass held a celebratory picnic in summer 2023 to thank citizens and in recent months the organization has held public events to continue raising awareness about growth issues in the Madison Valley. Yellowstonian had an interview with Counts, Smith and Arbogast. What they have to say parallels the kinds of concerns registering in the tri-state area of Montana, Wyoming and Idaho.

Our Interview

Todd Wilkinson/Yellowstonian: The Madison Valley has had generations of champions of rural land protection. Some have passed on in life or moved away and others have burned out battling the myth that private property rights should reign supreme, even if it results in the loss of what the larger community holds dear. I’ve heard people respectfully refer to you as “the three amigas” who helped jumpstart a re-awakening of citizen interest in addressing ever increasing threats to the Madison Valley, especially those clustering in the vicinity of Raynolds Pass and in the outskirts of Ennis. Your ad hoc organization, Preserve Raynolds Pass, was formed quickly. What was that like?

Kaye Counts: When one plunges into a deep pool, you don’t know what to expect, but inevitably you surface with a new perspective. I am one of those people. To build a strategy for solving a problem, a good approach is to dive in and try to understand everything possible about the situation, from historical, legal, financial and cultural angles. In essence, gaining a sense of the universe—i.e. all of the dimensions—of the situation. That reveals opportunities and weaknesses.

TW: Numerous citizen polling has been done up and down the Northern Rockies. Every single one reveals that citizens, of all political stripes, are deeply concerned about growth issues. However, as I travel around Greater Yellowstone and the larger Northern Rockies, I encounter many people who are alarmed by the transformative effects of population growth and development, but often they feel alone in their concern, or believe their voices will be ignored by elected officials who often give developers what they want. Why did you step up?

Kaye Counts: In deciding to be an advocate, I became more immersed in the valley and got to know my neighbors better. I listened to the stories of heritage families, learned about the science of water and the course of the Madison River, the critical nature of the landscape for wildlife and the fragility of Raynolds Pass, along with seeing it in the context of so many other western valleys. The result was a tremendous new appreciation for the value of our region on multiple levels and its connectivity to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which itself is set within the larger Yellowstone to Yukon corridor. I came to better understand the impact of climate change and how people can be great stewards of a special place or, by letting outside forces dictate its future, they can allow inaction to be its downfall.

TW: As with a recent public uproar in Paradise Valley over a proposed resort in Suce Creek, the proposed Marriot Hotel and airpark in Island Park and resort plans that have sprung up south of Jackson Hole, citizens don’t hear about developments until the 11th hour and then it might be too late to marshal scrutiny. County planning officials don’t always alert the public, and with the news media being in decline and fewer people subscribing to newspapers, information and awareness can actually travel slower in rural areas, not faster.

Kaye Counts: The RV park plan caused people to take notice. No one expected such possible degradation of the southern Madison Valley to appear out of nowhere. When some valley residents received a letter from the county announcing the RV park was being considered, they immediately began to reach out to one another. They contacted Marina who has been involved in landscape conservation for years and usually knows what’s going on. She began calling for more information as she didn’t receive a letter and, in her networking, looped Sam and me into the situation.

Sam Arbogast: Marina and her friends have taught me so much, opened my eyes to a whole new way of thinking, and I am still learning. When Marina let me know about the RV park application, we all said HELL NO. The three of us worked together so well. We all have such passion to want to fight for this place.

TW: Preserve Raynolds Pass has evolved into being a permanent non-profit, and, as you say, it isn’t going away. You’re now its executive director, Kaye. How did the threat galvanize public interest, among longtime residents, seasonal folks and even more recent newcomers?

Kaye Counts: The proposed RV park landed as a visceral gut punch to the residents who only learned about it via those notification letters per Madison County subdivision regulations. Only because the developer, by law, was forced to provide the public with notice of intentions were we given any advance warning. It caused many people to wonder what else might be looming out there.

“The proposed RV park landed as a visceral gut punch to the residents who only learned about it via those notification letters per Madison County subdivision regulations. Only because the developer, by law, was forced to provide the public with notice of intentions were we given any advance warning.”

—Kaye Counts, executive director, Preserve Raynolds Pass

TW: Sam, you and Kaye and Marina are no shrinking violets but you’ve said you don’t feel comfortable speaking out without gathering hard figures. What did your investigation turn up about growth issues around Raynolds Pass in a context even bigger than the RV park?

Sam Arbogast: I have looked at where subdivisions are located, what ranchland is under conservation easement and the location of parcels that are not currently under subdivision covenants. I have great concern for the parcels that are outside current subdivisions such as the 118.5 acres where the RV park was proposed. There are other large parcels that could be sold off and subdivided into smaller parcels, and there are some 20- to 50-acre parcels along the US Highway 87 corridor that are ripe for commercial development. Realtors are advertising these parcels as no zoning, no covenants, basically build and do as you please. I see this as very dangerous.

TW: Marina, you manage a couple of working ranches that provide crucial habitat for wildlife and are part of the visual grandeur of the southern Madison Valley. Your employers have placed conservation easements on their ranches and they’ve been widely praised by members of their community. Where do these properties fit within the cartography of permanent protection and why is it important for the southern Madison Valley?

Marina Smith: We have conservation easements on approximately 13,000 acres in the Raynolds Pass area. Elk Meadows Ranch and Three Dollar Ranch sit right in the middle of the migration corridors for elk, antelope and mule deer. The ranches also offer connectivity for other species such as bear, wolverine, cougars, and wolves. Conservation easements are vital to the valley because they allow these corridors to stay intact, without the disruption of large developments which hinder the movement of the animals as they try to navigate between mountain ranges and along the valley floor to summer and winter ranges.

Sam Arbogast: My primary ongoing concerns are also about the severing of the migration and connectivity corridors. In addition, of course, there are deep concerns about reduced water availability, reduced water quality, loss of habitat for many other species, several of which are threatened and reduced property values.

TW: Along with wildlife, could you elaborate on the concerns about water from the perspective of a rancher?

Marina Smith: Of utmost concern for many landowners in the area is water quantity and quality as well as maintaining the viability of wildlife passage. As more and more wells are punched into the aquifer, and our winters get lighter [with snowpack accumulation], I have seen the surface water decrease significantly and have seen springs dry up or seriously decline, which indicates to me that the sub-surface water is dwindling as well. The quality of the water, thankfully, remains good as far as I know but individual septics [systems for holding human sewage and wastewater] and the possibility they might fail, is out there.

TW: As a ranch manager, you are keenly aware of not only the importance of water for maintaining viability of agriculture but you’ve witnessed trendlines regarding precipitation related to snowpack, shifts in when water is available and when it becomes challenging— and the potential impact that lower water levels have on recharge of underground aquifers. You’re on the front lines, seeing things that people don’t comprehend when they turn on the tap in the city or suburbs.

Marina Smith: There is that old adage about not missing your water until your well runs dry. I grew up in a place where our well ran dry and can see the writing on the wall here. I can visualize where this place is headed and want desperately to slow the train down, selfishly, because I don’t want the change and don’t know where else to go. This is home, after having spent 40 years in Montana, I don’t want to go somewhere else, because this truly is “The Last Best Place.”

“There is that old adage about not missing your water until your well runs dry. I grew up in a place where our well ran dry and can see the writing on the wall here. I can visualize where this place is headed and want desperately to slow the train down, selfishly, because I don’t want the change and don’t know where else to go. This is home.”

—Ranch manager Marina Smith

TW: People who reside near rivers sometimes lack a sense of how surface water is a reflection of water flowing underground and present in aquifers. In Jackson Hole, for example, some of the water supply for town residents comes from the aquifer on the National Elk Refuge. In Paradise Valley, there’s concern that ground pumping from underground aquifers may create cones of depression because pumping is outpacing recharge.

Sam Arbogast: I am very concerned about our water availability in the Madison Valley and quality should we put in too many straws to drink from one aquifer. Some residents have noted they feel their well water level has decreased over the years.

TW: We are a society that loves to rally for underdogs. In the minds of your supporters, Save Raynolds Pass qualified as that. At first, some believed that successfully stopping the development was a longshot. That’s a sentiment present in many valleys where citizens think there’s nothing they can do.

Kaye Counts: Citizens often aren’t aware that we have options to save the character of our community. They are sometimes limited but they do exist and one of them is that public employees who work for the county must be transparent and put the interests of citizens ahead of private developers who sometimes arrive in our region believing they can influence decisionmakers with their swagger.

TW: That kind of sounds like the ruthless fictional capital investors who represent the villains in the TV show Yellowstone who treated locals as gullible yokels who could be bullied or bought off.

Kaye Counts: Our lawyer, Jecyn Bremer, was a trusted guiding light and informed citizens like Steve Dolcemaschio and Richard Stem were important advisors. They acted as sounding boards and shared their own experience and knowledge to benefit the outcome. They showed up at county Planning Board meetings with me when they could. It was a great comfort even as the Planning Board ignored the regulations and devised 42 mitigations to pass the RV park application to the commission with a recommendation for approval. Dark days, indeed.

TW: Based purely on the perception of this outsider, one could say that because citizens were neither apathetic nor silent, it made all the difference. Otherwise, there would be an RV park today. County commissioners listened to the issues you raised, overruled the planning board and voted to deny approval. Some say little victories can be the genesis of an awakening.

Kaye Counts: My sense is that the Mile Creek RV Park was a big wake-up call for residents, year-round and seasonal, and the proposal took the county by surprise. I believe elected officials in Madison County are aware and concerned, but that existing policies and processes slow down their ability to support protection of the valley.

TW: Looming ever large barely out of sight is the specter of Big Sky and the presence of Lone Mountain Land Company that is expanding its investment in gated communities for ultra-wealthy outsiders to the Shields Valley and flanks of the Crazy Mountains in Park County. If the Jack Creek Road, which represents a direct connection between Big Sky and the Madison Valley were not private and its use not restricted because of a conservation easement, there’s no doubt the Madison would become like Teton Valley, Idaho is to Jackson Hole. Yes?

Marina Smith: There is a huge ongoing concern about the growth of Big Sky and Bozeman spilling into this valley. It already has detrimentally impacted Madison Valley just in the sheer number of people who spill over and come here to recreate. Cliff and Wade lakes are prime examples and are areas that were once a favorite of mine and are now forever ruined just by the crowds that flock there to enjoy the beauty and “solitude” that no longer exists. They are only 20 minutes from my house and yet I no longer want to go there. The Madison River is so crowded that I no longer want to fish; the trailheads, once quiet, are now also busy. Change is not coming, it is here, and there seems to be little we can do to stem the tide.

“Cliff and Wade lakes are prime examples and are areas that were once a favorite of mine and are now forever ruined just by the crowds that flock there to enjoy the beauty and ‘solitude’ that no longer exists. They are only 20 minutes from my house and yet I no longer want to go there. The Madison River is so crowded that I no longer want to fish; the trailheads, once quiet, are now also busy. Change is not coming, it is here, and there seems to be little we can do to stem the tide.“

—Marina Smith

TW: Sprawl is spreading at breakneck speed in many valleys throughout the Northern Rockies. The Madison could be spared an unwanted outcome, planners have told me, if conservation-minded investors stepped forward. One irony, they say, is that the very people populating Big Sky and expanding the human footprint, could be part of the solution, instead worsening the problem. Justin Farrel in his book, Billionaire Wilderness, writes how Big Sky has a community of billionaires and mega-millionaires who have either been oblivious when it comes to understanding how globally-significant Greater Yellowstone is ecologically or they don’t care and are stingy when it comes to supporting large landscape conservation. Their attitude stands in stark contrast to others who genuinely are concerned about the well-being of nature serving a larger public good. It exists in the history of the Madison Valley.

Marina Smith: There was a push in the 1990s to protect the valley but the momentum dwindled in recent years, partially due to fatigue of having to fight developers who are exploiting weak planning and the inability to make little headway with zoning. The Madison Valley Ranchlands Group, which has been a strong voice, was pretty vocal for years. While they are still doing community building, such as forming a weed committee and turning its annual gathering into a social event, the group hasn’t really been active. I served on its weed committee in the 1990s. Weeds are an important concern for ranchers whose viability depends on having healthy grasslands but if you don’t slow down development we’ll be losing a lot more than pasture to weeds.

TW: Indeed, the Madison Valley Ranchlands Group was one of the sponsors of an extensive 2006 scientific analysis. The Madison has been among the touchstones in southwest Montana, along with the Big Hole Valley, in thinking about protecting large landscapes. A lot of people put in a ton of time and effort. What happened? I know of one prominent Bozeman-based NGO that had an active presence in fostering discussions about commonsense planning and zoning in the Madison but after its staffer left the organization almost 20 years ago, it more or less abandoned its involvement with land use planning.

Marina Smith: There were some key players who were really active back in the day. Talented, likable individuals who are out front—every community needs to have them—can serve as vital conduits. Brian Kahn—who owned a place in the valley, had a popular radio show and had worked earlier for The Nature Conservancy—being one of them. Since Brian passed away, his important voice was lost. I really missed him during the fight against the RV park because I knew he would have been a very vocal and effective advocate for our efforts. Rock Ringling, a leader with the Montana Land Reliance, also retired. Roger Lang, who was a really vocal large landowner, sold the Sun Ranch a few years after he worked with different entities and put a series of easements on it, which was huge. And there’s been Jeff Laszlo at Granger Ranches. Alex Diekmann with the Trust for Public Lands passed away and was another driving force for conservation here and is missed greatly. And there were Craig and Jackie Mathews who ran a fly-fishing business in West Yellowstone and brought Trout Unlimited on board. And there was the late rancher Lynn Owens and now his daughter, Linda Owens, and, of course, John Crumley. There are others. Altogether, the network of interpersonal relationships was priceless.

(NOTE: In this video below, from a decade ago, conservationist Craig Mathews speaks as the former manager of the Sun Ranch and ally with Trout Unlimited and the Trust for Public Land about the world-class attributes of the Madison Valley and what still needs to be done to secure its safekeeping. Mathews was a co-founder, along with Yvon Chouinard of Patagonia, of 1 % for the Planet, and for many years, he and has wife, Jackie—also a committed conservationist—operated Blue Ribbon Flies in West Yellowstone, Montana).

Kaye Counts: We’re trying to rebuild that web of larger connection. I should note that we’ve been in contact with people like Bob Kiesling, who for decades has been a connector of people in conservation real estate, land trusts, ranchers, and buyers who want to preserve the pastoral and wild character of Montana, not treat it as only a commodity. We’ve also reached out to people like Mark Petroni, who worked for the Forest Service and served on the planning board.

[NOTE: Kiesling is co-editor of a new book coming out in May 2025 on the legacy of Montana land trusts titled Saving the Big Sky: A Chronicle of Land Conservation in Montana. Read the guest op ed Kiesling wrote for Yellowstonian].

TW: One irony about the current state of urgency is that Madison County has been talking about planning and zoning for decades. Former Madison County Planner Doris Fischer recognized the need for being prepared to deal with growth when Tim Blixseth and the Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks and Moonlight Basin were coming on line and going before the planning offices of both Madison and Gallatin counties. In the face of racing development and unscrupulous speculation in real estate, it’s obvious that voluntary conservation, by itself, isn’t enough.

Marina Smith: The people who put easements on their ranches are rightfully viewed as heroes. Madison Valley has a baseline of ranch protection may valleys do not. Fortunately, those protected ranches can serve as anchors for a possible visionary next step. They were really vital and did much to safeguard the valley aesthetic you see today, but there are key pieces that are vulnerable and in urgent need of conserving. We don’t have a lot of time. Several of us have been trying to quietly work on getting this to happen but have not had success yet.

TW: What do you think is behind the defiant perception in the Madison Valley among some that trendlines can be ignored, that planning and zoning aren’t necessary? You’ve lived in pastoral landscapes yourself that incrementally vanished, but none of them had the caliber of wild nature that still exists here.

Sam Arbogast: There is a sense of place and peace that brought us to the Madison Valley, and it is a counterpoint to crazy lives people had in the city. If we allow rampant growth and commercial development to happen, this place will be changed forever. The reason we all came here will be no more.

TW: To invoke former Madison County chief planner Doris Fischer again, she noted that decades ago Madison County was the first county in the state to have a planning board and the first county to implement a comprehensive plan that functioned as a growth plan. Contrary to claims from anti-regulation activists that having sideboards on development would stymie growth, she said it hasn’t. Let’s bring the conversation back to what’s at stake for the Madison Valley’s world-class wildlife.

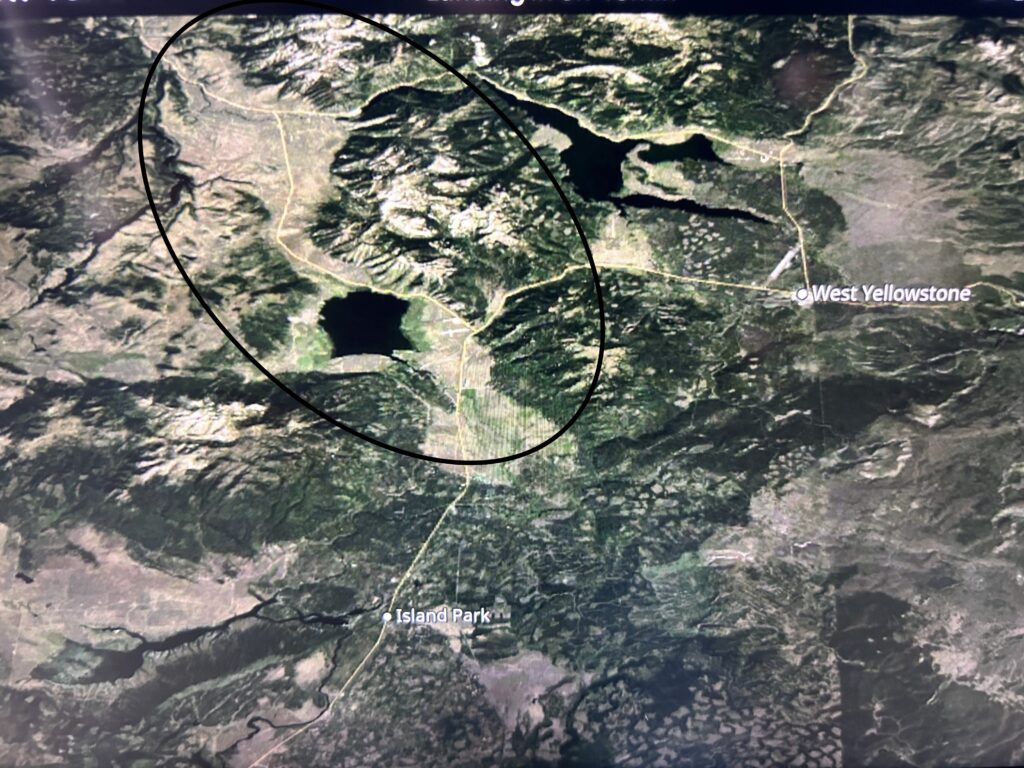

Sam Arbogast: There are places where the migration and connectivity corridors can be severed, where wildlife may not be able to traverse the valley from one mountain range to the other if growth is not managed in an intelligent way. There is a study on collared pronghorn that shows the movement from winter to summer ranges that show them going right down the valley and over Raynolds Pass to Island Park. It’s a really cool video to watch if you haven’t seen it.

TW: In November, a similar grassroots effort organized in part by the Henrys Fork Wildlife Alliance on the southern side of Raynolds Pass helped persuade Fremont County to at least temporarily deny the proposal for a Marriott Hotel and private residential airpark along Idaho Highway 20, for now. Interestingly, a spokesman for that development last summer claimed that the wildlife migration corridor does not exist and that livestock grazing on the land for four generations had disrupted wildlife movements. It’s located right across the road from a working ranch protected by easement with The Nature Conservancy precisely because it holds high wildlife values.

Kaye Counts: I think of wildlife and concern about its survival as a symbol that unifies people. Along with the recent 20-year drought and its wildfires and effect on forage, the tough winter of 2023 hit wildlife and livestock hard. Witnessing the shrinking of the pronghorn herd here was painful. A similar scenario happened in Wyoming. Pronghorn are less adaptable than elk and with the increasing density of buildings and people on our road [US Highway 287] over the last 16 years, I see fewer pronghorn traveling through our part of the valley. I fear that I will see a significant decrease of the herd sizes in my lifetime. If we come together now, that doesn’t have to be inevitable.”

TW: Some have compared the mentality of certain realtors and land developers to that of hustlers on the front end of a mining boomtown. Many will reap profits and then move on. Protecting a world-class place, I’ve heard asset managers say, is actually a great underlying strategy for protecting property values.

Sam Arbogast: For those concerned about property values, whose belief is zoning will negatively affect their property value, I say think of it this way: Do you think someone looking to buy your home or land would pay top dollar if there were a hotel or truck stop two lots away? Or would they pay more for a home looking at open space, wildlife, that has plentiful, good drinking water? I would not buy my own house if a truck stop or a Marriott Hotel were to be built right behind me. If just one commercial development is allowed to happen, this opens the door for more and more. Again, if we don’t set standards, we will lose this place.

A hotel and the constant human busyness it brings would have permanent impacts in ways that working ranches do not. What have you learned in your ongoing consultation with experts, be they scientists, wildlife managers, ranchers or professional planners who understand how quickly landscapes can be negatively changed in ways that cannot be undone?

“For those concerned about property values, whose belief is zoning will negatively affect their property value, I say think of it this way: Do you think someone looking to buy your home or land would pay top dollar if there were a hotel or truck stop two lots away? Or would they pay more for a home looking at open space, wildlife, that has plentiful, good drinking water?”

—Sam Arbogast

TW: If you’re a transplant who hasn’t been in the valley very long and have come from a highly urbanized landscape you may not understand how a little bit of sprawl can have huge permanent impacts on a wildlife migration corridor that’s existed maybe for thousands of years.

Kaye Counts: Newcomers are challenged to see the difference between the valley 10 and 20 years ago, and now. For them, Madison Valley now looks pretty good, and the fragility of the ecosystem is not apparent. They need to educate themselves about the reality of what’s here, the same as we’ve done.

TW: Few people realize that when one lives in a wildlife-rich valley, maintaining that alone is an investment in property values. The same way that we maintain our homes for possible resale value, and value good schools and maintained roads, wildlife presence is a huge asset yet once sprawl surpasses a tipping point and wildlife values dimmish, that added value, which few other areas of the country can claim, goes away. Sprawl, those who have studied it intensively have told me, impacts quality of life in other ways.

Sam Arbogast: I would add that, regarding sprawl, there’s growing concerns for public health and safety which we demonstrated during the RV park opposition. There are very long wait times for any type of police/fire/medical response in this remote area. Current county subdivision regulations reference this and provide for concrete response times as they consider granting approval of subdivisions, but they cannot be met out here. And to provide them comes at cost, which means taxpayers in many cases are paying for tax increases they don’t want in order to pay for development they don’t want.

TW: A few national planning experts have told me that forcing citizens to pay for sprawl is a kind of an unfunded mandate imposed upon taxpayers. Another pervasive sentiment I hear from talking to people around the ecosystem is that many county commissioners and local state legislators, avowed fiscal conservatives, are in denial about rural growth impacts and costs—even as sprawl imposes huge fiscal burdens and accelerates the loss of community. By the time they wake up they may have lost the ability to act.

Kaye Counts: Turning a big ship is a slow and careful action. While the looming threats call for immediate protective action, today we must focus on raising awareness in the community and with giving elected officials the tools they need to achieve the best result in the long run.

TW: You still have hope that people will continue to rally, finding a way forward?

Kaye Counts: There is so much at stake here in every possible dimension and I wouldn’t have truly understood that without painstaking research, outreach to experts and listening to the people who know and love this place. It feels as if 20 years of life at Raynolds Pass was compressed into a year and a half. I look forward to continuing to learn. The answer is yes, we’ve found that once people realize the Madison is more than a pretty backdrop. Its rural lands are home to a world-class concentration of wildlife; people want to help save it, on both sides of Raynolds Pass, in valleys throughout Greater Yellowstone.

TW: As a grassroots effort, how can people help your Preserve Raynolds Pass campaign?

Kaye Counts: Our two great needs are educational outreach and financing to pay for the outreach and legal support of community goals. We need people to talk to people about what is at stake and that good change, such as managing new growth and stopping large commercial development is a benefit to everyone. Management of new development protects water, land, wildlife habitat and more. By doing so, management of new growth protects property values. Let’s not be afraid to talk about that. We hope to develop a recipe of engagement and education that others can use and adapt for the benefit of the county and its people.

ALSO READ: Meet The Real Madison—And Why It’s Called ‘A Mini-American Serengeti’

About “The Three Amigas“

Marina Smith, softspoken and introverted, has a poetic, gentle way of describing rural life in the West. She knows her way around a horse, has managed cattle and sheep, cleared debris out of irrigation ditches and has calloused hands to show for mending (wildlife-friendly) fences and being subjected to bitter cold during lambing and calving seasons. People seeing her in her element might be shocked on where the journey of her life began.

“I have always loved wild places, and my parents instilled that in me at an early age. We camped when I was a kid, although I grew up deep in the heart of a city in Southern California,” she says. “We escaped to the forests and deserts of surrounding states every chance we got. The wild places flushed the smog out of my lungs, and the peace and quiet of these places regenerated my young soul; I was hooked.”

By her example, it’s not where you start; it’s what you allow yourself to become when one feels belonging to a special place. As soon as Marina turned 17, she left home and struck out to find her way, always drawn to remote places. “Southern Oregon, the Shasta and Scott Valley of northern California and the eastern Sierra were all places I called home before I found Montana,” she says. “I lived remotely in the bush of Alaska for two years, but Montana was in my blood, and I could not bear to be away from it, so I moved back once again.”

Marina has lived in Montana for 40 years and on a drive from Raynolds Pass northward to Ennis she can point at yard lights at night, identifying the places of the old-guard ranching families, sharing a bit about their history. A naturalist and dog lover, she has watched wildlife populations rebound. Whether they can stay healthy, she says, will come to down to human choices and the values informing decisions. The rapid suburbanization of Southern California may be in her past, but similar patterns of growth, without pondering the ecological consequences for Montana, could be its undoing. She is an optimist but also a pragmatist.

Kaye Counts is a person of the mountains and her affinity for them started in the East.“ The Appalachians don’t hold a candle in size to the peaks of Montana, but they have nourished the hearts and minds of generations of families who lived on the land,” she says. “My ancestors settled there and through sustenance and truck farming, blacksmithing and moonshining created a life for themselves.”

Counts has a fondness for rural people and a natural way of conversing with country folk who have connections to each other and the land. “Through the generational stories in my family and especially those shared by my dad, I learned to respect and honor the hills, rivers and valleys there and the critters within them,” she explains. “The West had mystique for us, as it does lots of people. My parents loved Yellowstone Park, and my mother was an early bird buyer of a digital camera so she could capture their repeated experiences there. She and my dad told me stories of the beauty of the surrounding areas, Hebgen lake, the Madison River and Raynolds Pass.”

Back in Appalachia, Counts witnessed firsthand destruction of mountain top removal coal mining and its associated pollution run-off that could occur at a landscape level, leaving places and people impoverished. While companies enticed workers with jobs and employment, they were exploited the same as the land was, often with profits exported to outside shareholders and local residents left with messes that destroyed their home ground. It’s a story that people in Butte know well.

“In West Virginia as a young adult, I saw fish leaping to their deaths on riverbanks rather than remain in the heated, chemical laden Kanawha River. The mountains and hills were stripped for coal and left barren to erode, unable to support life,” she says. “There was loss everywhere. My family could only acknowledge the loss, and I am motivated to offer my time and skills to protect special lands where it is not too late.”

Sprawl and development, of the kind that has ballooned around Big Sky and built to serve the short-term interests of outsiders, represents a major threat to the priceless wonders of the Madison Valley that cannot be replaced. For many, the Madison River is sacred and ought to be treated that way, she says.

Sam Arbogast grew up recreating in the Santa Cruz mountains of California. She rode horses. One of her favorite activities was laying down a pad and sleeping out under the stars in places where the lights of development pressure did not mute the clarity of night skies. “I loved the open space, and all the wildlife found in it. My love for animals has been lifelong. My first job at the age of 15 was at a vet hospital. I wanted to be a vet for as long as I can remember back in childhood. Life took a different path. I am a registered nurse now,” she says.

Sam first came to Montana with her husband in 2001. They stayed in West Yellowstone but spent days fishing the Madison and returned for two week stretches in the years that followed. “I found myself spending more time watching everything surrounding us than actually fishing. This valley just called to me/us. I can’t explain it. We have come every summer since then. We have seen the growth. Every year there was more and more homes here. Not just the Madison Valley but everywhere in this region. In 2012 we built our house near the Madison River. We would say to each other as we drove in each summer, “I wonder what new homes or buildings have popped up since last year.”

Sam says it’s not a matter of moving to Montana and not accepting change. It’s a matter of knowing that growth is going to happen but doing it wisely and using the best available information to protect the natural elements that set the southern Madison apart in the world. “This, of course, may sound hypocritical that we built here and now sound like we want to close the door behind us, but I think I learned more about this place the more time I spent here, I learned it needs protecting,” she said. “The more time I spend here, the more I learn about it, learn about its creatures and how fragile it is.”