By Leon Kolankiewicz with Rob Harding

In the fall of 2024, we were proud to release our latest study on sprawl affecting a very special and today still one-of-a-kind place: Greater Yellowstone: An Ecosystem at Risk.

We enlisted longtime journalist and Yellowstonian’s own Todd Wilkinson to write the study’s inspiring foreword. Last September, I [Leon Kolankiewicz] presented part of study’s findings at the 16th Biennial Scientific Conference on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem sponsored by the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee, comprising the major federal and state land management agencies in the region.

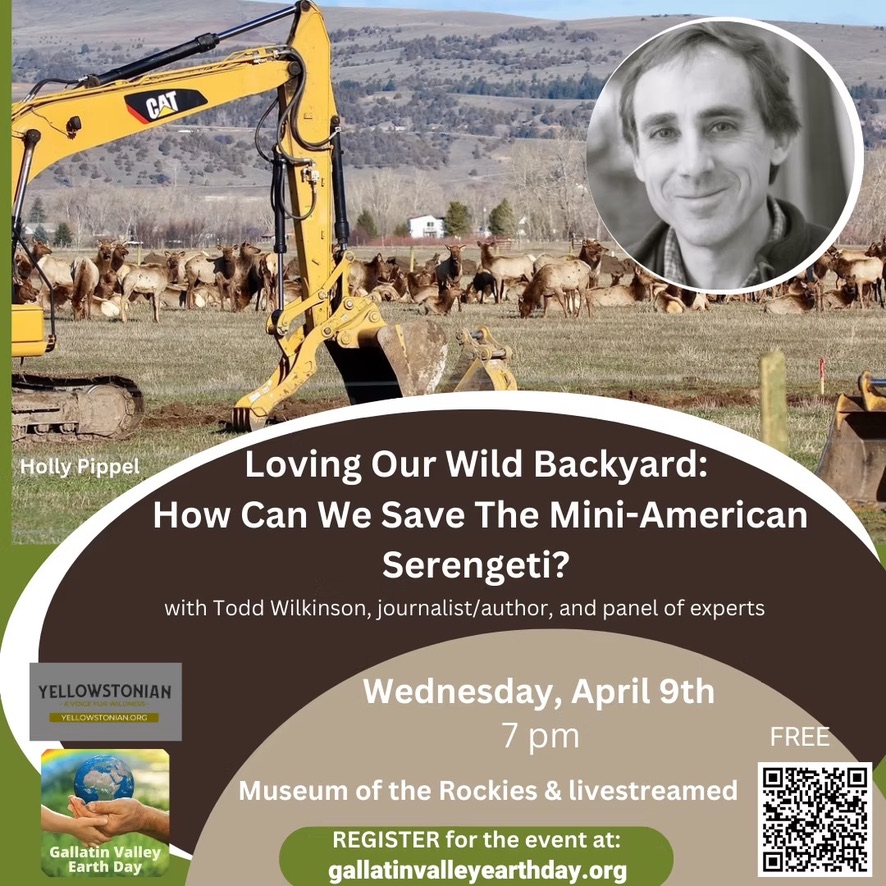

That event was held at Big Sky, Montana which, as a sprawling backdrop set in a once wild place, made the case for what happens when respect for the critical places wildlife need is lost to boomtown attitudes and real estate speculation. On Wednesday night, April 9, 7 pm, at Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, parts of our findings will be highlighted in a panel discussion with five experts on landscape conservation led by Wilkinson and sponsored by Gallatin Valley Earth Day. Our colleague, Eric Ruark will be on the panel and I [Rob Harding] will have hard copies of our study available free. You are invited and if you can’t make it to Bozeman you can click on this Zoom link to pre-register and attend remotely.

All of the prior studies I [Kolankiewicz) have been involved with, through NumbersUSA, have examined the roles of human population and corresponding consumption in the permanent loss of America’s rural lands and their conversion to urbanized or developed lands. Greater Yellowstone in recent decades has dealt with an unprecedented influx of newcomers moving here mostly for lifestyle seasons or to build vacation homes.

Not only have many of the newcomers built new structures in rural areas important to wildlife and water quality, as well as local culture and working agrarian operations, they’ve located them inside the Wildland Urban Interface that is prone to burning from wildfires. In total, the size of their footprints of impact have been disproportionately larger and more disruptive, ecologically speaking, than their predecessors. This is yet another dimension of Greater Yellowstone’s current titanic challenges being caused by sprawl.

They’re plainly obvious in the Gallatin Valley, Big Sky, southern Jackson Hole, Teton Valley and Island Park, Idaho; they’re beginning to manifest writ large in Park and Madison counties in Montana and Star, the Upper Green, Hoback, and Bighorn valleys in Wyoming. The time to take action is not when when natural areas have been lost or the costs of repairing them too formidable. The most efficient, cost-effective actions that will leave us remembered as wise ancestors is protecting the best that remains that it’s still possible and having a plan.

Not only have many of the newcomers built new structures in rural areas important to wildlife and water quality, as well as local culture and working agrarian operations, they’ve located them inside the Wildland Urban Interface that is prone to burning from wildfires. In total, the size of their footprints of impact have been disproportionately larger and more disruptive, ecologically speaking, than their predecessors. This is yet another dimension of Greater Yellowstone’s current titanic challenges being caused by sprawl.

Rural lands consist of agricultural lands (farms and ranches), wildlife habitats, and open space. Healthy and abundant rural lands are critical to America’s, indeed any country’s, long-term ecological, economic, and aesthetic well-being. Their incessant degradation and disappearance is utterly unsustainable, evidence of a system that is out of balance.

What makes the Greater Yellowstone study unique among our 25-year series of urban sprawl studies is its emphasis on wildlife and wildlife habitat. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE)—“America’s Serengeti” —deservedly enjoys worldwide renown for both its wildlife populations and for its storied role in the history of North American wildlife conservation and the global national park movement.

Yellowstone Is A Crucible of American Wildlife And An Emblem For Why Wilderness Conservation Matters

In his foreword to our recent study, Wilkinson writes that: “Greater Yellowstone [has] Yellowstone, the first national park in the world, at its geographic heart. The ecosystem that encompasses the park is today considered the most iconic wildlife-rich bioregion in the Lower 48 states, renowned especially for its concentration and diversity of large free-ranging native mammal species rescued from near-annihilation at the end of the 19th century.”

The GYE is the only substantial, mostly intact ecosystem in the Lower 48 states that still sustains the entire assortment of species that existed before European contact/conquest. Among the native, free-ranging mammals found then and now are both grizzly and black bear, cougar, gray wolf, coyote, wolverine, fisher, moose, elk, mule deer, bison, pronghorn, and mountain sheep.

A hundred years ago, three of these species – the grizzly bear, wolf, and bison – had already been decimated in Greater Yellowstone and most of the American West – or were well on the way to being so. Their relative recovery in Greater Yellowstone to stable or increasing numbers is a splendid example of wildlife conservation’s broad progress in the 20th century.

This should be seen in the wider context of other recoveries and relative success stories of imperiled species supported under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973. Many of them are actually large, majestic birds, such as the bald eagle, peregrine falcon, osprey, brown pelican, whooping crane, and California condor. Tragically, Endangered Species Act protections appear to have arrived too late for another great bird teetering on the brink of extinction, the ivory-billed woodpecker of America’s southeastern swamps, which has probably already been pushed and plummeted into the abyss of permanent oblivion.

The ESA has also helped safeguard threatened and endangered mammals such as the black-footed ferret (rescued from oblivion near the Greater Yellowstone community of Meteetse, Wyoming), Florida manatee, and Florida panther (a subspecies of the same mountain lion that occurs in this ecosystem). But it would be Pollyannaish not to acknowledge that, in spite of this bevy of heartwarming success stories, overall, North American wildlife and biodiversity have been severely impacted by the onslaught of industrial civilization. It is against this generally distressing temporal and spatial backdrop that the extraordinary contribution of Greater Yellowstone to wildlife conservation and hope for the future should be appreciated.

Of Greater Yellowstone’s 23 million-plus acres, about three-quarters are publicly owned and one-quarter are in private hands. The former are our cherished national parks, forests, wildlife refuges, and the like, and the latter mostly working farms and ranches, but with a growing acreage that is built-up to accommodate the region’s mounting human population.

As the number of permanent and seasonal GYE residents increases, so too does the number of buildings, structures, infrastructure, and facilities which fulfill urban functions. This includes furnishing goods and services expected and demanded by modern consumers: not just residential dwellings, driveways, and landscaped yards, but related commercial areas, utility infrastructure, streets and roads and parking lots, schools, office parks, workshops, and other job sites, recreation areas (e.g., soccer fields, tennis courts, golf courses), and so forth. In aggregate, the average GYE resident is associated with – that is, utilizes or “consumes” – more than half an acre of developed or urbanized land.

The lesser known secret about so-called prosperity driven by sprawl is that all citizens are asked/forced to subsidize the profits of developers, who gladly pass the costs of production off on the public as what economists call “externalities.” Few other industries in America benefit from such socialized costs as those in development and real estate, especially in states that refrain from assessing the total real costs of sprawl.

In Greater Yellowstone, another cost not being considered is the loss of wildlife, loss of open space, and loss of traditional farming and ranching which is translating into loss of community character, loss of local identity and loss of the cherished things that have set Montana, Wyoming and Idaho apart.

As Todd Wilkinson emphasizes in his foreword to our study, four factors historically once helped ensure the preservation of Greater Yellowstone’s wild character: geographic isolation, the vast extent of publicly-owned and protected lands, low human numbers, and the fact that most private lands were either agricultural (farmland/ranchland) or undeveloped open space. Nowadays however, three of these four factors – geographic isolation, small population, and limited development – no longer hold.

Greater Yellowstone’s private lands are found mostly in broad, lower-elevation river valleys. Think of the Gallatin, Paradise, Shields and Madison in the northern part of the ecosystem; Jackson Hole, the Centennial and Teton valleys on the west; the Upper Green and Star valleys in the south; and the Lander, South Fork of the Shoshone and Bighorn Basin to the east. All are coming under pressures from sprawl that, unless addressed, will leave them irretrievably transformed.

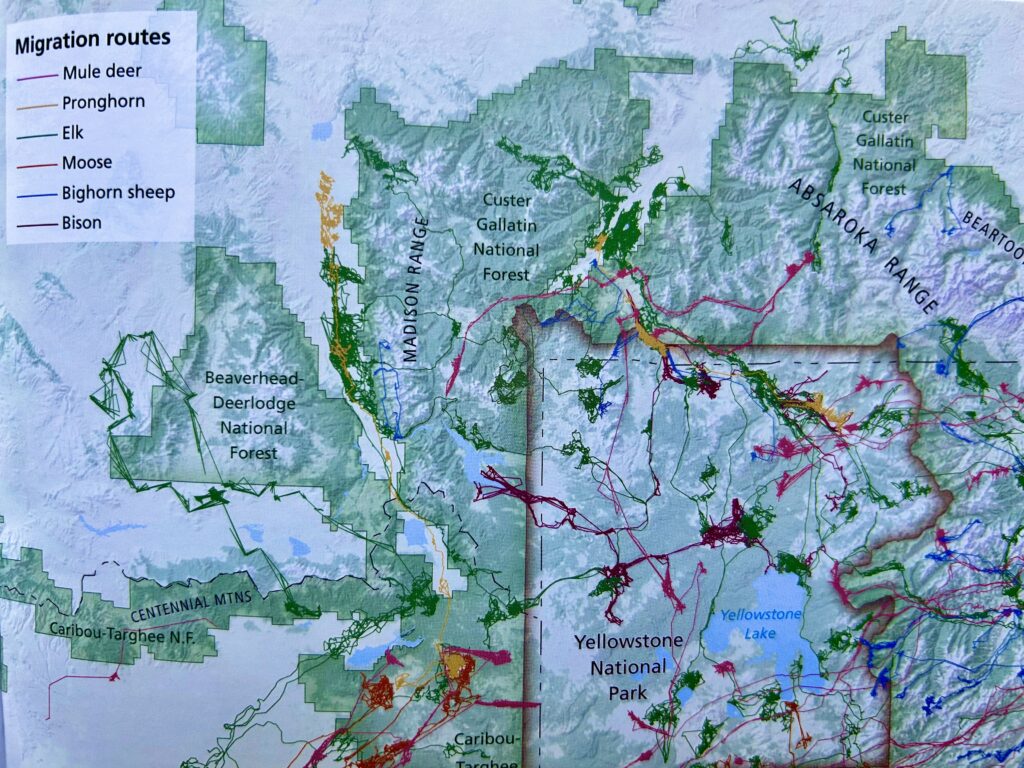

Each plays a crucial ecological role— “vital connective tissue holding together the superstructure of public lands”—in Wilkinson’s words. Larger mammals, especially ungulates, and a highly visible part of Greater Yellowstone’s unparalleled movements chronicled by the Wyoming Migration Initiative, depend on these private-land habitats to survive the arduous Northern Rocky Mountain winters.

Greater Yellowstone Has A Renowned Homegrown Legacy Of Brave, Visionary People Powering Conservation In The Face Of Opposition

A short stroll from the visitor center in Moose, Wyoming, in Grand Teton National Park one finds the Murie Ranch, dubbed the “heart of American wilderness” by the National Park Service. Here, for much of the 20th century, lived members of the Murie family: Wilderness Society director and acclaimed wildlife biologist Olaus Murie, his conservationist wife and author Margaret (Mardy), his brother and fellow wildlife biologist Adolph (author of the classic book The Wolves of Mount McKinley). Adolph’s wife, and Mardy Murie’s half sister, Louise, was also a committed citizen conservationist.

Olaus Murie has been dubbed “the father of modern elk management.” In 1927, the U.S. Bureau of the Biological Survey (precursor to Leon’s old employer the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) tasked Murie with researching and providing recommendations on management of the Jackson Hole elk herd, eventually culminating in his classic work The Elk of North America.

Elk were native to the central Appalachian Mountains of central Pennsylvania, where Leon now lives, but they were extirpated by the late 1800s with expanding human settlement, habitat loss, and relentless hunting. Half a century later, the Pennsylvania Game Commission worked with Yellowstone National Park biologists to capture and relocate Yellowstone elk, reintroducing them back to their haunts in the mixed deciduous-coniferous forests cloaking the so-called Allegheny Plateau (what geologists term a “dissected plateau” with deeply cut valleys on the edge of the Appalachians) of north-central Pennsylvania.

Greater Yellowstone’s pivotal contributions to the recovery survival of the wolf, grizzly bear, and bison are widely acknowledged and recounted elsewhere.

All of this, of course, is set within a larger context of the U.S. and our approach to stewardship, which is based on having public lands, which support public wildlife populations. Both these lands and wildlife are managed for the public trust, and common sense environmental laws co-written by elected officials on both sides of the political aisle.

The “Magna Carta” of U.S. environmental laws—the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) – specifically mentions that numbers of people, intensity and scale of developments are factors that must be considered as potential negative impacts on federal public lands. Today, insidious efforts are underway that could result in the gutting or bypassing of NEPA, which also guarantees citizens, including independent scientists, the ability to comment and scrutinize proposed federal actions.

But let’s return to the topic of population pressure that can be exerted on the sensitive and fragile lands of Greater Yellowstone in two different ways: the effects of sprawl on private land spilling over and impairing the ecological function of public lands; and industrial activities, including widespread, intensive outdoor recreation, disturbing or displacing wildlife from secure habitat, including, potentially, destroying the viability of wildlife migration corridors and winter range.

Population Pressures Negatively Affect Wildlife, Human Quality Of Life And People Who Make Their Living On The Land

Fifty-five years—more than half a century—has now elapsed since the first nationwide celebration of Earth Day in 1970. It was the brainchild of Gaylord Nelson (D-WI), the sitting US senator from and former two-term governor of Wisconsin. Nelson was inspired by “teach-ins” and protests against the Vietnam War that had proliferated in the late sixties. Thanks to his vision and the energy of young activists and organizers like Denis Hayes, on Wednesday, April 22, 1970, an estimated 20 million people—an incredible 10 percent of the U.S. population at the time—took part in tens of thousands of educational activities and community festivities throughout the country on behalf of Mother Earth.

That first Earth Day was the culmination of a decade of increasing environmental awareness and activism, sparked both by shocking real-world catastrophes and crusading books. The former included the devastating 1969 oil spill along the Pacific Coast of Santa Barbara, California and in the same year, the burning of a bridge over the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio, when the badly polluted river below caught fire and the flames engulfed the bridge. The latter included best-selling jeremiads such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) and Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968), which reached and affected many millions.

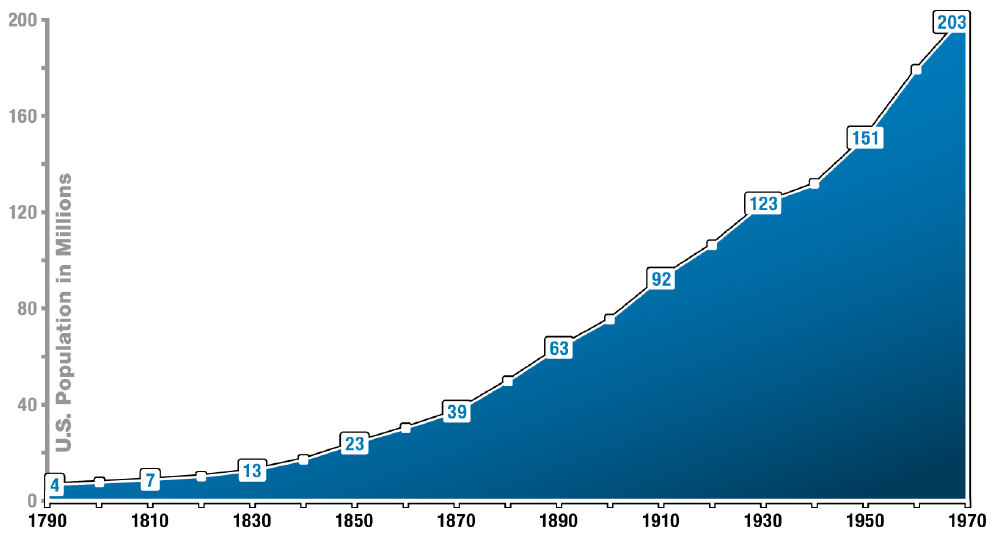

At the same time of the first Earth Day, in the previous two decades (1950-1970), America had undergone a population boom unmatched in our history, surging with over 50 million new residents (151 to 203 million), each of them a consumer of natural resources (like land and water) and an emitter of wastes (aka pollutants). Urban sprawl began to transmogrify the nation’s landscape in earnest, as bulldozers scraped away soils and plants to make way for asphalt and buildings; the countryside shrank and receded.

In this era, at the hopeful dawn of the modern environmental movement, the population factor as a force multiplier of environmental impacts was widely acknowledged by environmentalists, scientists, and politicians alike. As Stewart Udall (Interior Secretary during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations) wrote in his classic work The Quiet Crisis: “Dave Brower [iconic executive director of the Sierra Club] expressed the consensus of the environmental movement on the subject in 1966 when he said, ‘We feel you don’t have a conservation policy unless you have a population policy.’”

Gaylord Nelson himself was deeply concerned about overpopulation and an outspoken advocate on the topic for the rest of his life. Late in his life, he lamented to an audience in Wisconsin: “With twice the population, will there be any wilderness left? Any quiet place? Any habitat for songbirds? Waterfalls? Other wild creatures? Not much.”

Gaylord Nelson himself was deeply concerned about overpopulation and an outspoken advocate on the topic for the rest of his life. Late in his life, he lamented to an audience in Wisconsin: “With twice the population, will there be any wilderness left? Any quiet place? Any habitat for songbirds? Waterfalls? Other wild creatures? Not much.”

Today, some treat human population, and how it manifests unevenly across the landscape, as a taboo topic. While free marketeers in hindsight love to make fun out of the Ehrlich’s book, what laissez-fair economists in Bozeman still get wrong is their unfounded assertion that growth driven by the whims of short-term market capitalism, without rules and regulations holding it in check, results in better outcomes for precious wildlands and wildlife. If that were the case, a rare place like Greater Yellowstone would not be so rare, nor would it be in such jeopardy of being lost amid this latest wave development pressure.

For reasons that we will not dwell on in this article about population growth, sprawl, habitat loss, and threats to wildlife in Greater Yellowstone, Americans’ and even environmentalists’ concerns about excessive population growth and pondering the ecological impacts of sprawl peaked in the 1970s. By the 1980s, a powerful backlash to population worries and policies had begun to emerge on both the political right and left; its ranks swelled with certain religious folks, pro-lifers, libertarians, feminists, globalists, ethnic groups, economists, human rights and immigration activists, and believers in the “Bigger Is Better” ethos at the local, national, and global scales.

These strange bedfellows were united only by their unscientific and anthropocentric opposition to an acceptance of limits to perpetual growth of the human enterprise in the fragile ecosphere of a finite planet, the only known abode of life in the universe to date.

Global birthrates and average family sizes have indeed fallen dramatically over the past half century. However, in part because of what demographers call “demographic momentum,” and in part because of the resistance of the interest groups just mentioned, population growth itself, far from slowing or stopping, has continued almost unabated both in the United States and the globe as a whole.

Since that first Earth Day, the US population grew by 23 million in the 1970s, 24 million in the 1980s, 33 million in the 1990s, 27 million in the 2000s, and 22 million in the 2010s; there are now nearly 140 million more of us than there were at that first Earth Day—a nearly 70 percent increase! And U.S. growth accelerated in the first half of this decade because of the Biden administration’s de facto “open border” immigration policies.

The world adds more than 80 million new resource consumers/waste emitters annually, about 220,000 every day, at a clip on pace to add another billion in another 12 years or so. In a world already deeply into “ecological overshoot” i.e., exceeding carrying capacity as coined by the late William R. Catton, father of Greater Yellowstone conservationist Jon Catton, these demographic trends are lamentable and utterly unsustainable. A redistribution of population is bearing down on Greater Yellowstone and there is no regional strategy to deal with the influx, certainly not with impacts to the region’s unrivaled ecology in mind.

Ignoring population growth and its environmental effects does not make them disappear. Moreover, it does not take millions of people moving into a sensitive bioregion like Greater Yellowstone to have profoundly negative consequences. Other region of the US would love to have the natural attributes Greater Yellowstone does.

Pondering Urban Sprawl in America And Why Its Negative Effects Elsewhere Are Fueling A Land Rush Here

The national, Arlington, Virginia-based non-profit organization, NumbersUSA— for which we both work—published its first two studies on sprawl a quarter century ago in 2000: Sprawl in California and Overpopulation = Sprawl in Florida. We chose California and Florida because the former was (and is) the most populous state and the latter among the fastest-growing; in both states, sprawl and traffic were infamous. At that time, sprawl was a hot topic with many environmental organizations and the general public concerned about the impacts of ever-expanding urban areas and the nation’s steadily disappearing rural land. Vice President and later Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore had made it a personal cause in the late 1990s.

More than two decades on, sprawl is still devouring valuable farmland, ranchland, and wildlife habitat throughout the United States. But national, state, and local environmental groups, by and large, have turned their gaze away from domestic environmental and conservation issues toward more global issues like climate change. Concern about the loss of habitat and rural lands from the unsustainable outward expansion of cities in America, that is, urban, suburban, and ex-urban sprawl, has fallen out of fashion; sprawl is no longer seen as quite the “sexy,” cutting-edge issue it once was.

Yet, despite our country’s economic setbacks in and since the Great Recession of 2008, sprawl continues to threaten rural land and natural habitats in the United States. Nationally, in just the 10 years from 2007 to 2017, about 5,697,000 acres (that’s 8,900 square miles) of previously undeveloped land succumbed to the bulldozer’s blade. That’s an area larger than New Jersey’s 8,723 square miles and that volume of land has exponentially-negative spillover effects the kind of wild nature rare elsewhere but still found in Greater Yellowstone.

Indeed, according to the National Resources Inventory (NRI) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), in the 35 years between 1982 and 2017 alone, America lost 44 million acres to sprawl. That is, 44 million acres disappeared from the NRI land use category of “rural land” and reappeared in the NRI land use category of “developed land.” That’s equal to nearly 69,000 square miles, or 20 times the area of Yellowstone National Park. Cumulative sprawl, or the cumulative area of developed land in the country (excluding Alaska), according to the NRCS and NRI, was inventoried at 116.3 million acres in 2017 (181,720 square miles), or 52 times larger than Yellowstone NP. (As of 2025, 2017 is the most recent year for which data are available.)

Since those first two studies on sprawl in California and Florida in 2000, NumbersUSA studies have documented sprawl and the population growth factor helping drive it in about 10 other states—including Texas, Oregon, Idaho, Arizona, and Colorado—and several important ecosystems and bio-regions, such as the Chesapeake Bay watershed extending across portions of New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia, and the urbanizing southern piedmont of Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. We have also conducted three national-scale inventories of sprawl, in 2001, 2014, and 2022. Our research has been cited hundreds of times in the academic and technical literature in more than 20 countries and 10 languages, and many hundreds of times in the popular press.

Population Growth + Development + Sprawl = Habitat Loss

Greater Yellowstone has been a crucible of the American wilderness preservation movement nearly as much as it is for conservation biology. As filmmaker and conservationist Lois Crisler famously wrote in her 1956 classic Arctic Wild: “Wilderness without wildlife is just scenery.” Excessive human numbers and concomitant development are incompatible with both genuine wilderness and its wild denizens. This was recognized clearly and forcefully by the U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson, the aforementioned “father” of Earth Day, who in the final stages of his long life, was both a counselor to the Wilderness Society and an indefatigable campaigner for U.S. population stabilization.

A searing example of the fundamental incompatibility between incessant human population growth and wildlife in Greater Yellowstone was illustrated by a October 23, 2024 press release from the National Park Service:

On the evening of Tuesday, October 22, 2024, Grizzly Bear 399 was fatally struck by a vehicle on Highway 26/89 in Snake River Canyon, south of Jackson, Wyoming outside of Grand Teton National Park.

As will be familiar to Yellowstonian readers, Grizzly Bear 399, known as “the Queen of the Tetons,” was a 28-year old female believed to have been born in 1996; she was documented to have birthed 18 cubs, raising eight of them to maturity. She was the most famous beloved bear in America and perhaps the world, an authentic ursine celebrity. 399 was even the subject of an affectionate 2024 PBS Nature documentary. 399’s tragic demise symbolizes the relentless reality faced by Greater Yellowstone’s large mammals as human population, visitation, development/sprawl, and vehicular traffic all increase without apparent limit in this beleaguered wildlife haven.

Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife populations are in some respects healthier today than they were half a century ago due to greater public commitment to conservation and the tools and techniques of modern wildlife management. At the same time, GYE wildlife confront growing threats, among them climate change, novel diseases, invasive species, and jurisdictional disputes. Yet arguably, the biggest long-term threat of all is habitat loss and fragmentation because of rampant, spreading development on the ecosystem’s private lands. This development not only reduces habitat but impedes and disrupts ancient ungulate migration corridors.

In the past four decades, population growth, development, and sprawl on private lands within the 20 counties that comprise the GYE have permanently converted hundreds of square miles of rural lands – all of it agricultural land, wildlife habitat, or both – into developed or urbanized land. The resulting habitat loss and obstruction of traditional wildlife migration corridors have harmed the ecological integrity of the GYE and its large free-roaming ungulates and carnivores.

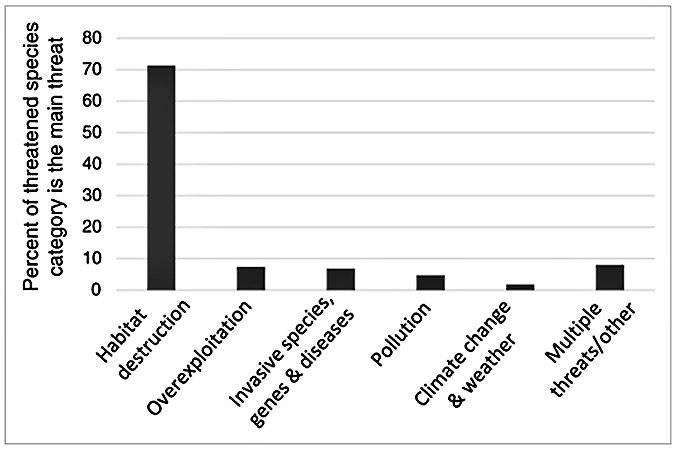

Worldwide, habitat destruction is widely acknowledged as the single greatest threat to biodiversity and viable wildlife populations. According to Salisbury University’s Aaron S. Hogue and Kathryn Breon, summarizing findings from the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and writing about threats to biodiversity globally in Conservation Science and Practice, a journal of the Society for Conservation Biology:

“…habitat destruction impacts more species than all other threats combined…and is the dominant threat to an extraordinary 40 times more species than climate change…. For the vast majority of species, it is the destruction of terrestrial ecosystems that is the primary problem.”

The GYE harbors long migration corridors for elk, pronghorn, and mule deer that extend well beyond public land boundaries into and across private land exposed to development. In the coming decades, current and projected rates and patterns of development across much of Greater Yellowstone would severely restrict or degrade crucial wildlife migration corridors.

Our GYE Sprawl Study: Data Sources and Methods

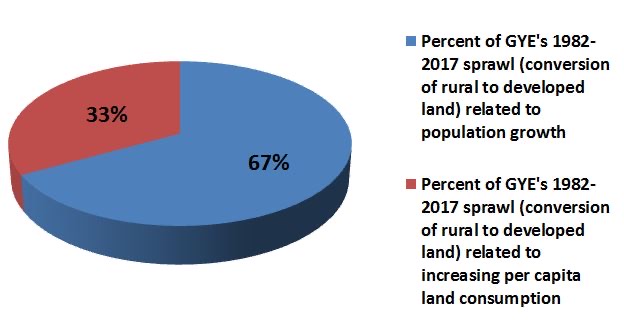

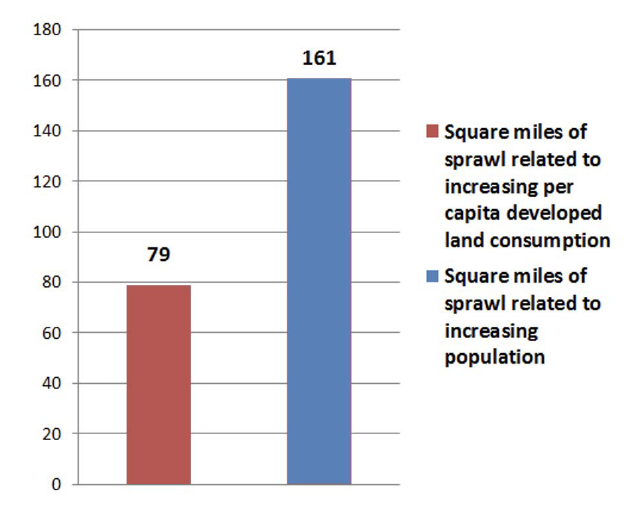

Our study quantifies the relative roles of two basic factors that drive increasing development on non-federal (mostly private) lands in the 20 counties that comprise the GYE: 1) population growth, and 2) increasing per capita land consumption, that is, decreasing population density.

We used a mathematical formula originally developed to estimate the relative weights of increasing population size and per capita energy use in determining America’s aggregate energy consumption. This “apportioning” approach to these two underlying factors can be utilized for any natural resource whose aggregate consumption is increasing over time. Such an increase can be due to a changing number of resource consumers, changing per capita resource consumption, or both. In this study, rural, undeveloped land – that is, GYE farmland/ranchland and wildlife habitat – is the natural resource in question.

We use “longitudinal” data (which chart changes over time in some quantity) from two federal agencies: the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS, formerly the Soil Conservation Service or SCS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Census Bureau (USCB). NRCS National Resources Inventories (NRIs) have estimated land use and cover on America’s non-federal lands county-by-county – all 3,144 of them – every five years since 1982.

One of the NRI’s land use categories is “developed land,” defined as those land surfaces covered with manmade structures or roads. (The NRI has three categories of developed land: large urban and built-up areas, small built-up areas, and rural transportation land.). The NRI documents changes, in 5-year intervals, in the estimated area of developed or built-up/transportation lands in all inventoried counties, such as the 20 encompassing the GYE. USCB estimates county populations annually. With both datasets available from 1982 to 2017 (35 years), we can derive estimates of the percentage of sprawl (defined as converting rural to developed land) in the GYE related to 1) population growth and, 2) increasing per capita developed land consumption.

“Per capita developed land consumption” is how much developed or urbanized land is associated with any given resident of a county on average. It is simply the area of developed land in a county (according to the NRI) divided by the county’s population (according to the USCB).

Take Home Lesson 1: Population Growth Drives Most Sprawl in the Greater Yellowstone

The area of developed non-federal land in the 20 GYE counties increased from 345,300 acres in 1982 to 497,400 acres in 2017, an increase of 44% or 152,100 acres (about 240 square miles). Approximately 67% (161 square miles) of this increase was related to population growth and 33% (79 square miles) to increasing per capita developed land consumption (see figures below).

In the most recent 2002-2017 subset of the entire study period, an even higher portion of the sprawl, 85%, and rural land lost to development were related to population growth. These results likely underestimate the adverse effects of low-density exurban sprawl on habitat fragmentation and large mammal migration. This driver appears to have intensified during and since the Covid-19 pandemic, as affluent out-of-staters poured into the GYE from places like California, building McMansions and ranchettes on often fenced large lots, which themselves can pose barriers to large mammal movement; this trend shows no sign of easing.

Take Home Lesson 2: Action Needed Both Locally and Nationally to Avert De-Wilding the GYE

If today’s demographic trends (see table) in the region were to continue into the future, by 2060, the aggregate population of the 20 GYE counties is projected to grow to 763,471, from 518,462 in 2020, an increase of 224,769 or 47%.

If the GYE’s average population density were to remain what it is today, this projected growth would entail the conversion of approximately another 250,000 acres (about 390 square miles) of non-federal rural land (e.g., wildlife habitat, ranchland) to developed properties. These newly developed areas would be unevenly scattered at varying densities throughout the GYE. The upshot is that their aggregate area and configuration – and the attendant habitat loss and fragmentation – would entail significant adverse, long-term direct, indirect, and cumulative effects on wildlife, especially large mammals and ungulates with large home ranges and/or long seasonal migration routes.

Averting this unacceptable, unthinkable outcome will require a combination of: 1) effective local, regional, and statewide planning and zoning measures and, 2) a genuine commitment to national population stabilization (pursuing zero population growth, or ZPG). Each of these is necessary, neither is sufficient by itself, to preserve the distinctive ecological character and irreplaceable wildlife of Greater Yellowstone.

With regard to #1, examples of such measures include:

- Smart growth and growth management tools

- Land use zonining

- Transfer of development rights

- Real estate transfer taxes with proceeds used to pay for and incentivize land conservation

- New funding sources for land protection

- Urban growth boundaries

- Open space bonds and supporting local land trusts

- Compact development

These measures and others have all been implemented extensively with varying degrees of success in communities throughout the United States. They would have the net effect of accommodating – not stopping – new population growth by increasing population density on new and already developed areas. In the GYE, these planning measures would require local political support and cooperation within and across three states and multiple jurisdictions.

To reiterate, both local and national efforts are urgently needed to ensure a generous future for wildlife in Greater Yellowstone.

What Is The Upshot?

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is a national and global natural treasure. Yet in this day and age, even beloved and supposedly protected natural treasures are often at risk. The GYE faces a number of long-term threats to ecosystem integrity, but none more immediate or insidious than that posed by incremental but unrelenting population growth and the development it spurs on private lands.

In an ever more crowded, degraded and uncertain world, the appeal of timeless, untrammeled wild and wide-open places – and the awe-inspiring, untamed creatures which roam there at will and live out their lives – is why so many people make pilgrimages. An increasing number of them are choosing to settle here permanently. This is the paradox and the conundrum we face. Americans are intrinsically drawn to the essence of Greater Yellowstone, and in order to be nearer to that wild nature, they are developing those lands, diminishing lot by lot the wild character that drew them in the first place.

In the GYE and everywhere else, there are limits to growth. It is a delusion to believe otherwise. What will we do with the opportunity and responsibility to act?

Click here to read an executive summary of the analysis of sprawl’s effects on Greater Yellowstone led by co-author Leon Kolankiewicz. Click here to read the entire study.

Also read these stories from Yellowstonian:

Wreckreation And Our National Obsession To Love Wild Places To Death

A Yellowstonian Exclusive: Watch The Documentary ‘Subdivide And Conquer: A Modern Western,’ For Free

What Happens When Greater Yellowstone’s Conservation Movement Goes MIA On Sprawl?

The Land Planner Who Tried To Prevent Disasters On Nature

Proposed Suce Creek Luxury Resort In Park County Is Just “Tip Of The Iceberg”

She Wants Jackson Hole To Regain Its Moxie As The Hub Of Courageous Conservation

Refusing To Surrender Wild Ground