by Yellowstonian

What’s your favorite beaver simile?

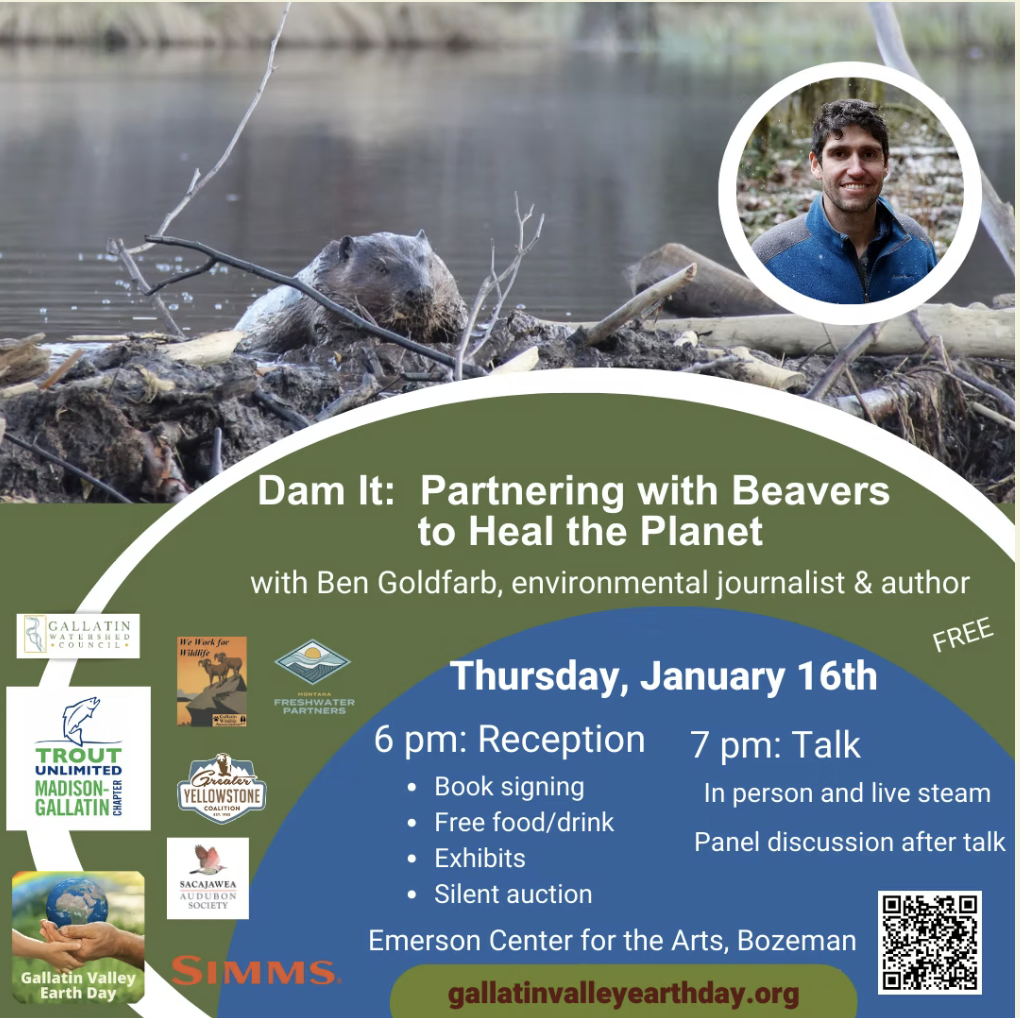

Ben Goldfarb is kicking off the 2025 Gallatin Valley Earth Day “Wild Talks” series in Bozeman by holding forth on the benefits of one of his favorite antidotes to climate change inaction—the beaver.

The title of his presentation is “Dam It: Partnering with Beavers to Heal the Planet” and the evening includes a panel discussion with Kurt Imhoff of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Connor Parrish of Trout Unlimited and Leah Thayer with World Wildlife Fund’s Sustainable Ranching Initiative.

Author of the award-winning and highly recommended boo, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter (available through your favorite local bookseller) Goldfarb is considered one of the beaver’s greatest champions. In addition to being keystone species, in that they create habitat for lots of other wildlife, Goldfarb believes beavers are also powerful allies in blunting the effects of climate change.

The free Gallatin Valley Earth Day event is Thursday, January 16th at the Emerson Center for the Arts’ Crawford Theatre in Bozeman. There is a reception at 6 pm and talk/discussion begins at 7 pm sharp. Bring your kids. Several other informative talks are coming in the weeks ahead and Yellowstonian is a co-sponsor. Story coming soon on Gallatin Valley Earth Day. Note: the event will be live-streamed via Zoom, but you need to register through Gallatin Valley Earth Day. Click on link here.

Not long ago, we had a chat with Goldfarb.

Todd Wilkinson: When did beavers first enter your radar screen—enough that you wanted to write about them and then gather enough material to produce a great book?

Ben Goldfarb: I grew up with an affinity for beavers; in one early memory, I’m canoeing on a lake at night with my parents when the serene dark is shattered by an explosive tail-slap. But I didn’t become a hard-core Beaver Believer until 2015, when I was invited to a beaver workshop near Seattle. I wasn’t quite sure what a beaver workshop was, but it sounded like a story; as it turned out, it changed my life. That day, one scientist after another got up to say their piece about why these critters, and the ponds and wetlands they engineer, were so crucial: for water storage, for salmon habitat, for carbon sequestration, for wildfire protection, for drought and flood mitigation, you name it. Beavers aren’t just industrious rodents, I realized that day — they’re one of the most valuable restoration tools in our box. I’ve been thinking and writing about them ever since.

TW: There are young, aspiring nature and environmental writers out there who often ask me how they can get their start. Often, I will steer them toward the intern program offered by High Country News, a great news outlet that I myself contributed stories to and wrote cover pieces for going back 30 years. Tell us a bit about HCN and how you cut your teeth working there.

Goldfarb: Like more western nature writers than I can possibly name, I began my career as an HCN intern. I can’t imagine a better training ground. HCN‘s readership is composed of agency staff, professional environmentalists, farmers and ranchers — in short, the most knowledgeable (and opinionated) people in the West when it comes to land management and politics. They know it all, and they’re not afraid to tell you that they know it all. HCN taught me to cover conservation with nuance and sensitivity, and to always keep those facts airtight — even a slight bobble earns a letter to the editor!

TW: In recent years, you’ve made more forays to Greater Yellowstone from your home in Colorado. In addition to your book on beavers, you recently wrote another provocative book about the impact of roads titled Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet. The great conservation biologist Dr. Reed Noss told me in the 1990s that nothing is ever so fateful for wild country as the decision to open it up via a new road and, in more recent times, to the creation of industrial strength outdoor recreation. What are a few things you learned while researching your book?

Goldfarb: It’s easy to imagine that the primary impact of highways on nature is roadkill: we’ve all seen the dead deer or elk on the shoulder. But roadkill is just the tip of the iceberg. The “barrier effect” caused by highways — all those racing vehicles forming a moving wall of traffic that animals can’t penetrate — can be an even bigger issue than road mortality. In Wyoming, for example, herds of mule deer sometimes starve en masse because they can’t cross I-80 to reach their historic winter range; in Montana, grizzly bears are famously impeded by I-90 and other highways, preventing isolated populations from interbreeding. In Idaho, the mere noise of traffic has been shown to disrupt songbird migrations. Even when roads aren’t killing directly, animals can’t escape them.

TW: I’ve been dying to ask you this question. Many people today have an impression that building wildlife bridges—overpasses and underpasses—is somehow a magical panacea regarding the preservation of wildlife migrations. But often lost in the way the media covers them superficially is that a lot depends on what’s happening on both sides of a highway. If it’s protected public to public land that’s being bridged, or private land that has conservation easements on both sides of the road, then it’s just a matter of engineering and paying for it. But many areas where there are high rates of vehicle-wildlife collisions have a problem of unchecked sprawl happening in close proximity. Wildlife collisions are an outcome of the problem of a lack of land use planning, yes?

Goldfarb: Yeah, I couldn’t agree more: If the land on either side of an overpass gets turned into subdivisions, all you have is a bridge to nowhere. That’s why our investments in wildlife crossings have to be matched — or exceeded — by our investments in conservation easements and other forms of habitat protection, so that crossings are embedded within corridors that will remain viable in perpetuity. We also have to address barbed-wire fences and other barriers to animal movement. And we have to do the unsexy work of reforming our land-use and zoning codes to prevent sprawl from devouring wildlands and cutting off migrations. Wildlife crossings help, in other words, but they’re just one connectivity strategy among many.

TW: Back to beavers. Ted Williams recently wrote a piece for Writers on the Range saying that beaver reintroduction isn’t appropriate for every place. In the West, where should our priorities be for bringing them back and are there things we as a country should be doing to hasten their comeback?

Goldfarb: I’m a great Ted Williams admirer, but I took issue with that column: Overwhelmingly our country’s problem isn’t too many beavers, but a lack of them. In the West, I’d guess that we’re at 10 percent of our historic beaver population, if that. So how do we get ’em back? In some places, live-trapping and relocation is appropriate; in others, building Beaver Dam Analogs can create the conditions that encourage their return. Most important, though, is simply not killing them. We lethally trap tens of thousands of beavers every year for conflicts such as cutting down trees and flooding roads; in so many of those cases, we could be using coexistence techniques instead. Turns out that if you let rodents live, they’re pretty good at repopulating their old haunts!

TW: We’ve both had great mentors who encouraged us early on. What advice would you offer to young people who have a love of nature and a yearning to make a difference in giving a voice to wildlife?

Goldfarb: Oh jeez, I’m not sure I’m qualified to give anyone advice. I think Ed Abbey’s famous injunction to be a “part-time crusader” and “half-hearted fanatic” is pretty good. Get out and enjoy the places, communities, and critters you’re trying to protect — you’ll know them, and yourself, better for it.

ENDNOTE: At the public reception, copies of Goldfarb’s books will be available for purchase and signing.