Introduction by Todd Wilkinson

Check out the breathtaking photograph above of Montana’s Paradise Valley taken by Jacob W. Frank, talented lensman employed by the National Park Service. For as inspiring as it is, the image is actually an optical illusion. Looking northward across the wending path of the Yellowstone River toward Livingston, and with the Crazy Mountains rising spectacularly above the Shields Valley in the distance, it offers an idyllic view of a large section of Park County, Montana.

The photo could convey an impression, a false one, that it will appear like this forever yet from even the moment Frank took it, ground was being broken for new homes. While many point to the other side of Bozeman Pass and express shock at the explosive growth inundating Bozeman and Gallatin County, consider this fact that should take your breath away: Park County is losing its open space at a pace 40 times the rate, per capita, than Gallatin. That’s because of low-density sprawl and the proliferation of what some call 20-acre ranchettes. Patterns of growth will ultimately determine whether Greater Yellowstone is able to retain its ecological integrity or lose it to the same kind of destructive patterns of growth that have de-wilded most other regions of the country. Good planning is about anticipating change and avoiding the worst effects rather than waiting to confront them.

We at Yellowstonian know that, for many of us, growth issues are difficult to wrap ourt minds around—particularly when it comes to assessing how trends present today will manifest in cause-and-effect impacts tomorrow. Human and ecological footprints are terms that apply to how much space development consumes and relatedly how that negatively affects things like wildlife and the habitat it needs to survive. There are related concerns about water quality availability, protection of open space and fiscal matters such as who is benefitting and who is really paying for the costs of growth.

The challenges before residents of Park County, Montana are a microcosm of larger macro trends transforming valleys in many corners of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and rural Rocky Mountain West. In June, voters in Park County will be going to the polls and voting on whether to repeal the county’s growth management plan—this at a time when growth issues loom larger than ever. Starting with this guest essay below and continuing with an ongoing series, we’ve enlisted the help of planning experts who will be writing about growth and sprawl in Greater Yellowstone. We at Yellowstonian further acknowledge that discussions of growth involving economics and regulations are often turgid, causing one’s eyes to glaze over. This ongoing series seeks to de-mystify the topics and make the issues easy to comprehend.

by Randy Carpenter and Robert Liberty

One million acres of open space lost just in recent decades in western Montana.

That number obviously isn’t sustainable, not for the remarkable natural character of any mountain valley, not for Paradise and the Shields valleys, nor for the good people struggling to make ends meet.

These are the twin prongs of growth that we’re tracking every day. They are not “building community” and, frankly, we can do better.

For those less familiar with Park County, it has been the historic scenic gateway to Yellowstone National Park, America’s first national park, which is a bucket list destination for countless millions of people around the world. Spatially, the county extends from the pastoral Shields Valley between the Bridger, Bangtail and Crazy mountains then extends southward across Interstate 90 to the banks of the Yellowstone River.

With the river coursing through Livingston and upstream flanked by the Gallatin Range to the west and Absaroka mountains to the east, the Yellowstone River leaves Yellowstone National Park at Gardiner, near the county’s southern boundary ending along the line where Montana meets Wyoming.

Change is happening briskly and we are nearing a number of critical thresholds that, if passed, we will never be able to undo—thresholds dealing with essential wildlife habitat, keeping farmers and ranchers on the land, mounting groundwater and septic concerns, open space whose views have been considered timeless, and growth that is creating fiscal headaches for local elected officials and resource-strapped citizens who are footing the bill.

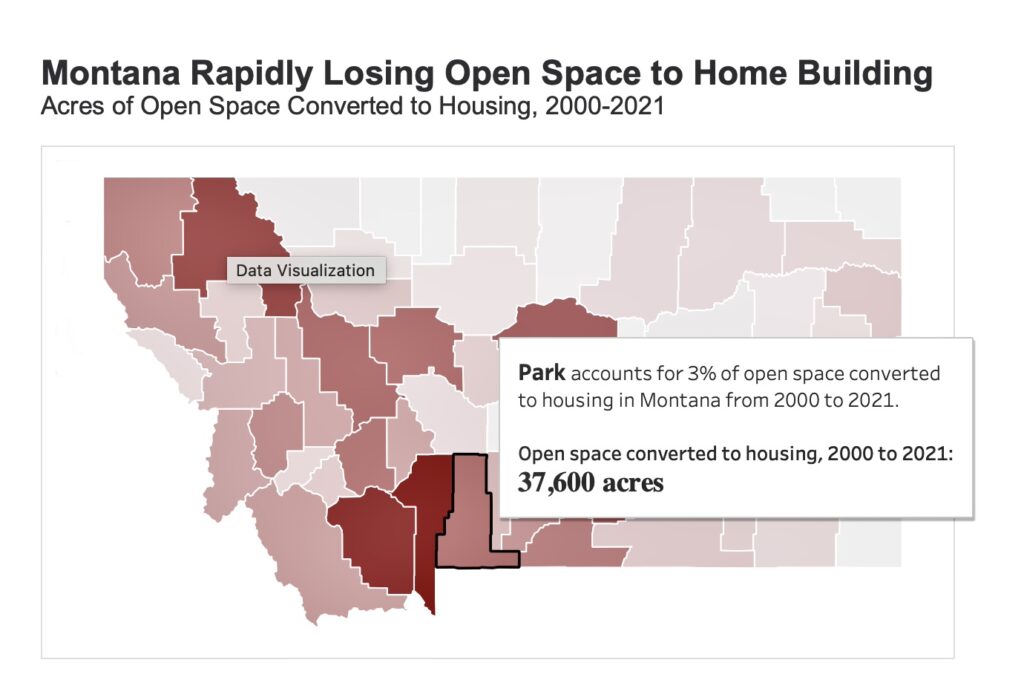

Recently, Headwaters Economics, an independent research group based in Bozeman, issued a report titled Montana Losing Open Space. The report quantifies what every observant resident of Park County, Montana knows, and it is summarized in these two paragraphs:

“Despite a recent acceleration in the pace of home construction, Montana residents are struggling to find affordable housing. A primary reason behind the lack of housing affordability is that a large share of Montana’s new homes are being built for affluent real estate buyers seeking large properties in the countryside.”

The one million acres lost in western Montana is equal to permanently removing half of one Yellowstone from the landscape but the erasure of natural lands that support incredible wildlife populations and sense of place is actually happening in many valleys found from the front door of Yellowstone north to the US border with Canada. Unmanaged growth is accelerating the changes, causing many to feel shaken by the reality that the Montana we love is disappearing and there seems to be no way to stop it. The same sentiments exist in booming areas of Wyoming and Idaho.

By “lost,” it means the natural things we value about those lands are vanishing and they will never return. This isn’t about being stuck in some dreamy nostalgia for the past. It’s about real problems and social trauma and the disappearance of natural features that make us proud to live here and excited to visit. Change isn’t just happening to us; it is the result of numerous choices and undesired outcomes that can be avoided, but it requires that we change the way we think about growth.

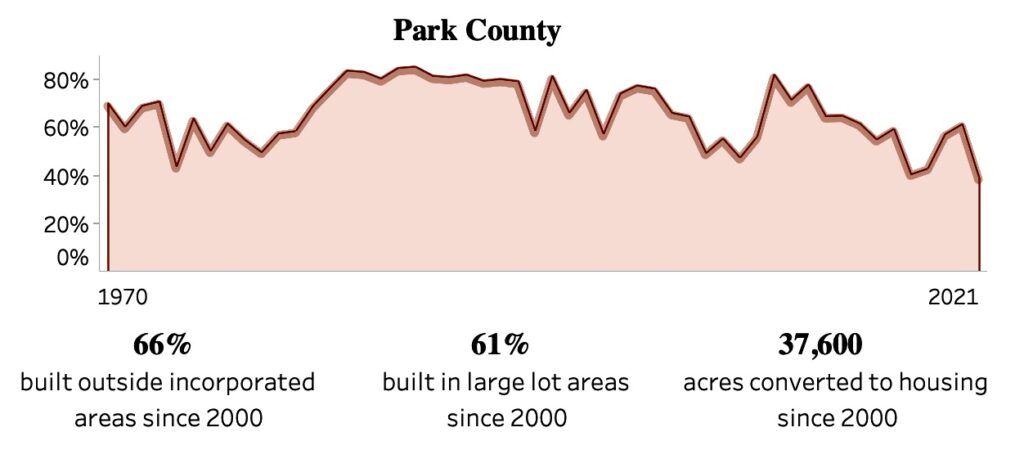

According to Headwaters Economics’ analysis of tax assessor records from 2000 to 2021, 56 percent of single-family homes in Montana were built outside of incorporated areas. Over the same period, 41 percent of Montana’s single-family homes were built in neighborhoods where lot sizes exceed 10 acres. The current proclivity for low-density residential construction in rural areas has resulted in the conversion of one million acres of Montana’s undeveloped land since 2000.

The report includes an interactive map to show open space development county by county. Here are two Headwaters’ graphics of the data for Park County:

Park County itself lost 37,600 acres between 2000 and 2021. To many, stats alone are meaningless. So, how much is that? It is just shy of 60 square miles. If this were aggregated into a block in Paradise Valley, it is substantial.

We’ve all read the growth-related reporting that has been done by journalist Todd Wilkinson in recent years on the impacts of sprawl to Greater Yellowstone. He has highlighted the eye-popping impacts that have beset Bozeman and Gallatin County which are among the fastest growing per capita in the country. And he has called attention to growth issues in the two side-by-side Teton counties of Wyoming and Idaho.

Regarding Bozeman, it has ranked among the fastest growing “micropolitan,” e.g. “small urban areas” in America and anyone who passes through it understands how it is negatively transforming the Gallatin Valley, accelerated during the Covid pandemic. Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley have become a symbol for many in Montana and communities around Greater Yellowstone of how not to thoughtfully grow.

But get this:

Park County, which is experiencing a number of spillover effects from Bozeman, is losing its open space at 40 times the per capita rate in Gallatin County. Read that again.

But get this: Park County, which is experiencing a number of spillover effects from Bozeman, is losing its open space at 40 times the per capita rate in Gallatin County. Read that again.

The Headwaters report uses a simple calculation to compare comparative per capita rate of open space loss. Between 2000 and 2021, Gallatin County’s population grew by 54,338 people (a 79 percent increase.) During the same period it lost 67,520 acres, or about 1.24 acres per additional person.

During that same period Park County’s population, according to the US Census, increased by just 743 people (a 5 percent increase) which seems nominal. However, in that same span Park County lost 37,600 acres of open space, which is about 49 acres loss per additional person. Yes, let’s state that again: Park County is losing open space at a per capita rate that is 40 times faster than Gallatin County. In fact, there were more dwellings built in Park County than the rise in local population, a statistic that isn’t reflected in Census figures.

Skeptical? Well, we think it’s important that you ask tough questions because engaged citizens demanding answers about the things that matter to them is the only way Park and other counties will be able to adequately plan for the future and avoid the worst consequences.

Three points we wish to make. First, there is growth which produces housing that serves the best interest of the local community and citizens who call it home—people who continue to make contributions to its essential fiber but who are feeling squeezed by economics.

Second, confronting the need for more affordable housing need not come at the expense of biological diversity in the form of sprawl that is also squeezing wildlife and leaving it homeless.

Third, and this is a key point: what’s happening in Park County shows that development which serves community interests (longtime locals who give much to their community) is currently decoupled from growth being driven by development that involves second homes and vacation rentals. In this Park County is hardly alone. It’s a problem facing many mountain towns throughout the Rockies.

In January 2021, the community conservation organization Friends of Park County made a projection about how much open space would be lost during these 2020s—and unfortunately it looks like we will be proved correct, unless we do something to change the trajectory.

In that year and month, newly formed Friends of Park County testified to the County Planning Board: “Based on the information we have now, we believe rural residential sprawl is a big threat to Park County. It’s not simply just the square footage that is part of the calculation of impact. It’s everything that comes with a new exurban property or subdivision that replaces former ag or undeveloped land. And all of this needs to be considered within the context of cumulative effects, for new sprawl is happening on top of the fragmentation that has already occurred and is not going away.”

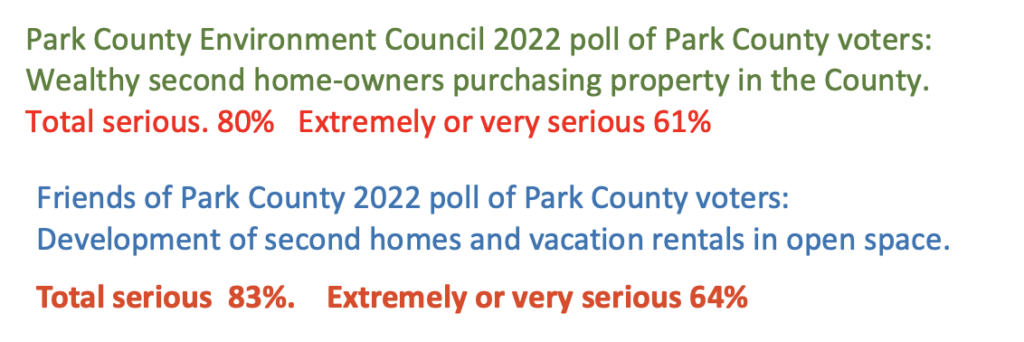

The graphics here spell out sentiments expressed by both Montanans and Park County residents in a series of recent opinion polls and surveys. It shows the percentage of respondents who think a given issue is “serious” as a concern and it’s worth noting the number who rate it as “extremely or very serious.”

Existing development is now a permanent fixture and no one is proposing that it be erased. It’s already taken a toll on wildlife and many residents are unaware of other other concerns that loom large.

In 2019, Park County issued about 115 permits for new residential septic systems. That may not seem like a lot. But, if each of those permits was associated with a 20-acre homesite, those new residential ranchettes would use up to 2,300 acres. At that rate, after ten years, there would be 23,000 acres of new low density rural residential development scattered across the county. Note: Manhattan Island in New York City covers 14,478 acres or 22.8 square miles, and Central Park, which seems huge, covers just 843 acres. The city limits of Bozeman cover 19.15 square miles.

In Park County, the amount of land that will accommodate those 115 permits, if each occurs on a 20-acre homesite, is equal to 36 square miles of new low-density residential development, equivalent to a strip two miles wide along US Highway 89 from Pray in the middle of Paradise Valley along the Yellowstone River to Livingston.

Our analysis of the growing imprint of development was portrayed by some as being alarmist—after all, there wasn’t a deluge of new giant subdivision proposals. In our response to this skepticism, we pointed to the county and state data showing the steady volume of septic systems and domestic wells being approved on existing undeveloped lots. That is, even without major new subdivision applications, significant second home development has been definitely occurring. If even if the inhabitants of those second homes sell and leave the county—many of whom only come here seasonally as it is—the footprint of their development creates a permanent footprint, including displacement of wildlife.

As it turns out, according to Headwaters Economics, the past rate of conversion from undeveloped land to sprawl is about 18,000 acres per decade so we think our forecast of 23,000 acres in coming decades will be proven to be very accurate—or possibly too conservative.

So what can we do about it?

Continuing the pattern of destructive rural residential sprawl is not inevitable; again, it is a choice. Montana law allows either property owners or the county commission to adopt sensible land use regulations. At this moment, however, a ballot initiative is looming. In June 2024, voters in the county (strangely those living in incorporated areas like Livingston cannot vote) will go to the polls and decide if they want to undo the existing county growth management plan. If the county growth plan is dismantled, it will set back the progress, though modest at best, that already has been achieved.

We ask: is this really the right moment to be repealing the county’s growth plan? And for those spearheading the effort to kill it, what is their vision for Park County considering that so many citizens are not happy with how it is changing?

Effective zoning and subdivision regulations, which balance private property rights with public responsibility and long-term common interest, have been adopted in many parts of Montana. We, along with Park County citizens, elected officials and members of the business community, toured examples of good and bad planning in neighboring Gallatin County in 2022 and 2023.

Strangely, at a time when some are pushing to undo better oversight, voters in a number of surveys have expressed their concerns about the unwanted head-spinning changes.

Consider just a sample of the results of a 2022 scientific poll of Park County voters. The voters were asked whether they would support various measure to manage development and focusing new residential development in existing communities had wide and deep support. Below, you can view Friends of Park County’s short video describing the results from three different polls. It is narrated by Friends of Park County board member Kathy Foote, a fourth-generation Montanan.

The county and property owners have the tools to protect Park County’s lands, resources and community character. We ask voters to support meaningful action and always to ask tough questions. We can’t wait for the next report to be written, laying out the consequences of further inaction.

Subscribe

Never miss a story, subscribe to our newsletter!