By Calvin Servheen

When I sleep, I dream about riding on two wheels. I, like a growing number of people in the American West, have a fever. And the only prescription is getting on a mountain bike.

There’s something addictive about hesitating at the crest of a high ridge, wind whistling in the pines, looking out into the vast blue distances and then surrendering to gravity’s pull. There’s something surreal about that inexorable tug, dragging you ever faster down into a wormhole of dirt and barreling tree trunks. I live for the thrill of riding my own tremendous kinetic energy through gritty straightaways and around swooping turns.

Mountain people of many different stripes can find an element of poetry in their favorite activity, and as a result we often feel a tug toward our personal wormholes of obsession. It feels wonderful to find a captivating outdoor activity. However, any of our favorite pastimes can come with subtle external costs. In our region where growing populations and rapid changes in the way we recreate are putting unprecedented pressure on ecosystems and wildlife, we all probably need to temper our desires in order to avoid loving our wild lands to death.

Now is a critical moment for conservation and I believe it’s more important than ever for us recreationalists to see our own environmental impacts clearly and strive to preserve the places we love. As a mountain biker, I will focus here on how my sport is impacting the natural world, with the hope that the ideas discussed could apply to many similar debates concerning the environmental and social impact of other outdoor activities.

Mountain biking has a unique dress code. Most of us wear stiff shoes, loose fitting attire whose only requirement is that it look ‘rad’, and an almost comical assortment of padding and cranial protection. However, our only truly mandatory items of apparel are a thick rime of spattered muck and dust, an eggshell shellac of sweat, and perhaps a few streaks of blood from various scrapes and cuts. Mountain biking can be a brutal endeavor demanding strength and endurance, a highly strategic sense for choosing lines, and an ability to effectively mitigate extreme physical risk.

Those of us who wear the biker’s uniform often struggle to get along with other recreation users. Just the other day, I had a most unpleasant interaction with a hiker on a pastoral morning ride in Bozeman. I was listening to The Rolling Stones on full volume and clattering down a narrow, pitted trail. Approaching a short incline, I let my momentum carry me up, over the lip and into the air, and back down onto a flat, raised section of trail. The maneuver had eliminated almost all my speed and I landed with a dolorous thunk on both tires.

As I rolled forward at about 5 miles per hour, a woman a hundred or so feet down the trail jumped and whirled around glaring. She faced me like some kind of knight defending her feudal territory and I was half afraid she wanted to haul me off my bike and share her obvious frustration in the form of a beating. Finally deciding to use her words, she bellowed “You have to warn me you’re coming!”

Bewildered, I gestured to what was in my mind a significant space between us. She continued to glare as I slowly passed with a chagrined and apologetic expression on my face. I don’t fault this hiker for her reaction because it’s likely she had a bad experience with another of my kind.

I conjecture that being strafed once by some hotdogging enduro bro polarized her into a growing community of recreationalists who wish those goddamn bikers would just go away for good. Unfortunately for her, mountain bikers are doing quite the opposite.

I conjecture that being strafed once by some hotdogging enduro bro polarized her into a growing community of recreationalists who wish those goddamn bikers would just go away for good. Unfortunately for her, mountain bikers are doing quite the opposite.

Despite its difficulty and danger, the sport is incredibly popular and has a thriving culture of adherents. Mountain biking is actually one of the fastest growing and most lucrative segments of the outdoor sports industry in the American West. Numerous mountain bike companies call our region home. They have cultivated a strong population of avid riders who tie their communities together and help maintain a growing number of local trail systems. While some of us may have hesitations about the sport’s rapid growth and what that might mean for ourselves and the environment, it’s important to recognize that mountain biking is a source of community, a precept for fitness, and a salve for the mental health of many.

Joyful yet dangerous, popular yet controversial, mountain biking is a sport of contradictions. Indeed lately, some deep and disturbing dissonances have begun to occupy my biking brain. Recently, I have felt a growing disquiet as research reveals the true environmental impact of riding bikes in wild places, and a cultural divide grows between gravity sports enthusiasts and conservationists. Many conservation journalism sources, including The Yellowstonian, have reported on the impact of outdoor recreation— and mountain biking specifically—on wildlife and ecosystems. Some of these publications have also served up savage critiques of the sport. I would like to offer my views as someone who stands on both sides of this deepening cultural divide between predominantly young action sports enthusiasts and the established conservation community in Montana.

As both a mountain biker and a conservationist, I am working to reconcile three major incongruencies between the sport I love and my commitment to conserve wild places: 1) the environmental impacts of riding; 2) the disregard for these impacts among riders; and 3) the rhetoric that drives division between riders and everyone else. In the face of growing evidence that pressure from outdoor recreation is negatively impacting wild ecosystems in the American West, we all must wrestle with these three deeply entrenched incongruencies in order to avert a recreation-caused collapse of our beloved ecosystems. I believe this discussion, while urgent in connection with mountain biking, also has bearing on a number of other conservation-recreation dilemmas. We will need to adjust our philosophy many more times as the population of our state grows and as outdoor recreation continues to evolve.

Philosophy Shift 1: Recognize the Environmental Impact of Recreation

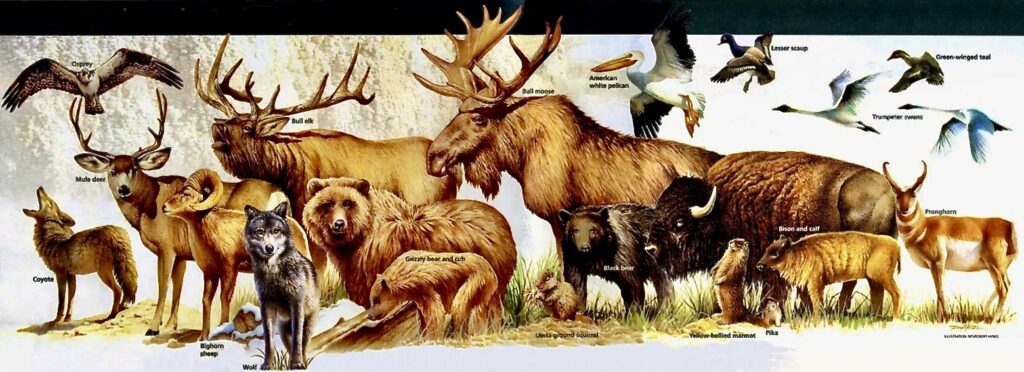

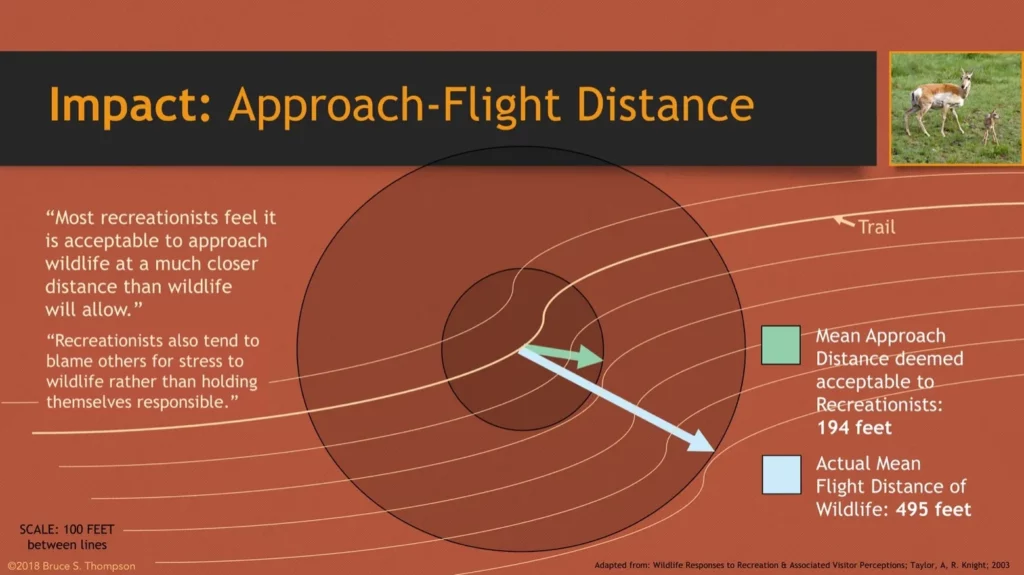

It has been widely reported in The Yellowstonian and elsewhere that many recreational activities have direct, measurable impacts on the ecosystems where we recreate. It has been demonstrated that these impacts come in numerous forms far more subtle than for instance litter, denuded vegetation, or soil erosion on trails. We can see the aforementioned impacts clearly each time we recreate, and public support for mitigating them is correspondingly strong. However, researchers tell us that far more damage is happening invisibly. Recently, it has been shown that many outdoor activities including mountain biking and hiking can significantly affect wildlife movement, contributing to higher levels of stress hormones and lower reproductive success in many species.

If you haven’t heard this news, here’s some background reading on how recreation impacts ecosystems:

- Elk responses to trail-based recreation on public forests

- An article on mountain bike impacts on wildlife

- A literature review of many effects of mountain bike trails

- A peer reviewed paper on recreation impacts

These are a mere sampling. A full body of findings, when considered in total, provide a very substantive reason to limit a variety of activities in wildlife habitat. However, in my discussions with my bike riding friends and colleagues, I often hear these findings dismissed as incomplete or incorrect. When I rather pedantically reiterate that my claims originate in ummm… peer-reviewed science, I often have to duck as they fire back knee jerk one-liners about the importance of access.

These findings provide a very substantive reason to limit a variety of activities in wildlife habitat. However, in my discussions with my bike riding friends and colleagues, I often hear these findings dismissed as incomplete or incorrect. When I rather pedantically reiterate that my claims originate in ummm… peer-reviewed science, I often have to duck as they fire back knee jerk one-liners about the importance of access.

While access to public land is indeed important, we shouldn’t use accessibility as an ideological shield against accepting that recreation has real and significant impacts. When I press further in these discussions, my peers invariably change the subject. Like your friend who won’t hear a word against her smelly good-for-nothing boyfriend, the inconvenient truth is apparently too disruptive to infiltrate these folks’ skewed mental model of what seems normal and reasonable.

By now I am used to smelling the funk of cognitive dissonance whenever I bring up this subject. Indeed, I often smell it on myself after a long bike ride and I’m forced to roll down the truck windows to let the crisp mountain air dispel my worry. How could my favorite sport and my love of wildlife and conservation be so mutually exclusive? What sacrifices might I need to make in order to do my part for wildlife conservation? Asking these questions makes me feel sad and uncomfortable because maybe the answers will involve significant personal sacrifice. Maybe I just shouldn’t bike anymore.

The more I wrestle with these issues, the more I recognize the fallacy of approaching biking vs. wildlife as simply a binary choice. I believe that mountain biking and many other life defining activities we love can exist in a world where we effectively preserve ecosystems. I have to believe we can have both. But how?

Recently, under the shade of giant pines with the dank earthy smell of loam wafting on a cool mountain breeze, I asked a simple question to a large group of riders: how can we make mountain biking more ecologically friendly? The answers came in mixed. One friend suggested stricter trail use regulations. Another advocated for more condensed trail centers to funnel traffic away from the pristine cores of national forests. Another rider focused on limiting e-bikes. Most however disputed my premise. Mountain biking, they maintained, is plenty sustainable, thank you very much. The notion of setting limits on where bikers can ride, while still supporting the sport’s growth into ecologically acceptable zones felt to them like an unacceptable and unnecessary compromise.

The idea that the mere presence of humans can damage an ecosystem doesn’t sit well with most of us. The subtle impacts we have on wildlife aren’t visible to us in the same way as soil erosion or trash, so it’s easy to question if researchers really know what they’re talking about. How could I possibly be affecting wildlife reproductive success when on most rides I don’t even see wildlife? This argument of course forgets that wildlife fleeing from humans is the problem.

The idea that the mere presence of humans can damage an ecosystem doesn’t sit well with most of us. The subtle impacts we have on wildlife aren’t visible to us in the same way as soil erosion or trash, so it’s easy to question if researchers really know what they’re talking about. How could I possibly be affecting wildlife reproductive success when on most rides I don’t even see wildlife? This argument of course forgets that wildlife fleeing from humans is the problem.

Facts like these aside, nobody likes being singled out as the cause of a problem. Many mountain bikers feel targeted by a conservation movement that in their view doesn’t understand riding culture and hates seeing bikes on their local trails. These sentiments definitely exist but they should not distract us from the data. Everyone must accept that us bikers, together with many other users like hikers and trail runners, are inflicting real damage on wildlife and natural ecosystems through our activities on public land.

Philosophy Shift 2: Challenge the Culture of Pursuit and Performance in Action Sports

Once we accept the fact that recreation has an impact on wildlife ecosystems, we need to agree around a corrective action plan. This process is where ideologies really begin to collide, so I propose we wrestle with another incongruence in our thinking: how much do we really care about nature? Or more specifically, how much do we value wildlife and the wilderness quality of the places we recreate?

Many authors far more eloquent than I have spoken about the power of reverence for nature. Thinkers representing all camps within the conservation community from Edward Abbey to Robin Wall Kimmerer, have spoken about how a personal connection to the natural world can be life defining. For some, reveling in the awe of nature is the only reason to get outside. However, many of us have other, less philosophically refined motivations.

Mountain bikers for instance are often motivated by a desire for personal challenge, to progress and build on our technical skills, and to experience the meditative flow of performing incredibly complex maneuvers at a high level. Pick your favorite outdoor activity and you will no doubt think of many factors that motivate you, other than connecting with nature. I think it’s ok to focus on self-growth in the outdoors, but not without some level of respect for nature’s beauty. We should all recognize that no recreation group has the right to degrade the wild character of public land for their own ephemeral enjoyment.

The truth is that every outdoor activity has an impact. When faced with a choice between the desire to bike, hike, trail run, ski, or whatever else you do and the need to stay the hell off the landscape for its preservation, we are really confronted with a hard philosophical question: are our human wants more important than the wellbeing of a natural ecosystem? Despite espousing conservationist talking points and ascribing to a conservationist personal aesthetic, most recreationalists whom I assail with this moral dilemma have a clear stance. They flat out admit that wild places have value primarily because of their recreation amenities. Usually, these folks are willing to sacrifice very little enjoyment in the name of true existence-value conservation.

The truth is that every outdoor activity has an impact. When faced with a choice between the desire to bike, hike, trail run, ski, or whatever else you do and the need to stay the hell off the landscape for its preservation, we are really confronted with a hard philosophical question: are our human wants more important than the wellbeing of a natural ecosystem?

This is likely unexpected and alarming for most readers of the Yellowstonian – a publication that amplifies conservation advocates – to hear, but the widely-held view underscores a large and growing cultural divide between an older demographic of conservationists who hike, watch wildlife, identify birds and plants, and seek naturalist knowledge, and a younger generation of intense, performance-oriented outdoor athletes who ski, mountain bike, trail run, climb, and overall have a very different relationship with the land. Many mountain bikers are in this latter demographic, and perhaps this explains our hesitance to accept the impact we have on wildlife. While we see ourselves abstractly as conservation-minded, when the rubber meets the trail, the wilderness character of the places we enjoy just isn’t that valuable to us. The integrity of wild places certainly doesn’t seem important enough to dissuade those who dig user created trails, push the limits placed on bikes by National Forests and The Wilderness Act, or defy science-based regulations on when and where riding is allowed. This paradoxical behavior is like matter-of-factly proclaiming ‘I don’t drink’ between heavy sips of PBR.

Many of us who fall on the more extreme end of the outdoor user spectrum are guilty of seeing the outdoors as a venue – a means to achieve personal goals and feel the fulfillment of conquering adversity. There are many positives to pursuing personal growth in the outdoors. The wilderness has been my greatest teacher, and I would not be the person I am today without its influence. However, many of us crawl down the wormhole of obsession in our activity of choice, forget to revel in the sacred beauty of wilderness, and begin to make decisions and hold opinions that contravene our outwardly proclaimed conservation virtues.

We could all benefit from taking a step back and truly appreciating the places we recreate. I have found for myself that intentionally reconnecting with the wilderness as a friend, not a consumer of its amenities, brings perspective on what really matters and reaffirms my commitment to conservation.

Philosophy Shift 3: Refrain from Hardline, Anti-Bike Rhetoric in this Debate

Once we agree that these impacts are real, and our shared reverence for wild places drives us to pursue better recreation policies, we need to make sure the policy solutions we find work for everyone. Mountain bikers are here to stay, and no solution to this dilemma will succeed without our support. To gain mountain bikers’ support, conservation thought leaders need to distribute the burden of whatever limits are placed on land use fairly among all recreation user groups. While I believe mountain bikers should recognize many limits to when and where we can ride, it is not feasible for non-bikers to regulate the sport out of existence as has happened in places like Marin County California, the birthplace of mountain biking. This scorched-earth policy approach would deepen existing divisions between riders and non-riders and lead to a surge of unsanctioned activity.

Conservationists must accept that well maintained, fun trail systems will need to be developed sustainably in order to stem the tide of user created trails and trail poaching. In my estimation, the 10 most exciting mountain biking trails in Bozeman currently are all user-created. Compare this to a community like Bellingham Washington, where sanctioned, public bike infrastructure offers some of the best trails in the world. Yes, there are still user-created trails in Bellingham, but there is far less of an incentive for the average biker to ride them compared to in Bozeman where mountain bike infrastructure is limited.

Conservationists must accept that well maintained, fun trail systems will need to be developed sustainably in order to stem the tide of user created trails and trail poaching. In my estimation, the 10 most exciting mountain biking trails in Bozeman currently are all user-created.

There are many places where mountain bikes should not go, but there are also abundant places where highly condensed trail centers could be developed sustainably to provide excellent riding close to town while reducing pressure on sensitive, remote ecosystems. Take for instance Copper City near Three Forks Montana, Beacon Hill in Spokane Washington, or Galbreth Mountain in Bellingham. These trail centers serve to concentrate mountain bike activity in one place, away from key wildlife habitat, while helping to revitalize degraded timber and mining land. Seeing support for projects like these from conservation leaders could bring bikers on board with limiting activity in more sensitive, pristine areas.

Conservation and sustainable development often feel like separate issues, but if you’ll forgive me for getting painfully abstract, both movements should be aiming toward the same goal: to create a world that sustains humans and ecosystems in perpetuity. Long ago we learned that a system-level perspective is necessary for effective conservation. Nevertheless, there is an equally long history of conservation stakeholders who want to remove every user group to which they don’t belong from public land.

It is becoming accepted in the climate change discussion to assert that it’s not enough for individuals to value only the welfare of themselves and those like them. Instead, we must think about how to meet the needs of everyone. Similarly in conservation circles, stakeholders must recognize that all of us have a legitimate claim to use public land in a reasonable way. As a society, we need to agree about what constitutes reasonable use, and that definition needs to leave room for activities beyond simply ‘what I like to do and nothing else.’ Strong anti-bike rhetoric will only fuel division and dysfunction in this debate. We must find a compromise solution.

It would be negligent after all in this discussion of problems to leave you without any suggested solution or path forward. The ‘solution-free rant’ is an unfortunately common phenomenon in conservation writing. For this reason, I can happily justify inflicting my unqualified and amateurish opinions upon you by proposing a 5-part plan to balance what we understand about the needs of wildlife with the interests of recreationists:

- Create a Collaborative Working Group – We must first create a task force consisting of leaders from the mountain biking community, conservation nonprofits, and relevant wildlife and land management agencies with the goal of finding a compromise solution to attack the threat to wildlife head on while supporting mountain bikers’ claim to use public land in reasonable ways.

- Identify and Establish Ecological Constraints – This group must agree on what constitutes reasonable use. First, scientific research and management best practices must inform a set of limits on use to protect the ecosystem. Then, guidelines for reasonable use and non-use must be drafted and agreed upon. Simply ignoring or denying the science must no longer be accepted as a strategy.

- Consider and Develop Mountain Biking Infrastructure Within these Constraints – Once a landscape-level strategy has been created, that recognizes and prioritizes key habitat areas, trail use maps must be designed to allow bikers access to plentiful fun trails in acceptable zones.

- Work to Build Cultural Consensus – Public outreach seems like the only way to reduce the social acceptability of subversive activity like building user-created trails and poaching hike-only areas. In addition, public outreach could cool reckless calls to drastically expand access for electric bikes and unwisely allow bikes in designated Wilderness areas, which are vital for healthy wildlife populations.

- Strongly Limit Unsanctioned Activity – Enlist the help of everyone to curb any activity that pushes beyond the collectively agreed upon limits to public land use by bikers, while providing epic biking opportunities in less ecologically sensitive areas.

This plan is just a rumination. While significant research and public outreach are still needed to address the emerging environmental repercussions of mountain biking and other activities, there is already a lot of data to draw upon. I feel strongly that any solution should be approached through collaboration between recreation users, wildlife managers, and researchers. We must all accept the facts. There is strong evidence that current recreation behaviors are damaging ecosystems. To avert a crisis, recreationalists need to rediscover within ourselves a deep personal commitment to respecting the boundaries of ecosystems and wildlife above all else. In addition, all interested parties must pursue fair, collaborative solutions that respect every user group’s claim to a common cultural and scientific definition of reasonable use.

For conservationists, it’s easy to forget that beneath that rime of muck, sweat, and blood, we mountain bikers are joyful creatures, motivated by community, the thrill of personal challenge, and an intoxicating sense of wonder for flying through deep forests and over rocky escarpments like the wind in the trees. Most of us do have a deep connection to the places we ride, and we should get the chance to be a part of protecting our local ecology. Mountain bikers come from a diverse range of political and socio-economic backgrounds. Conservationists must recognize that we represent a powerful potential ally in the fight to preserve wild places. Such an alliance would simply involve agreeing to certain limits on the types of trails we can ride, the places that must be protected, and the areas that can sustain better riding infrastructure.

For mountain bikers, it’s easy to forget that conservationists speak up from a sincere desire to protect something beautiful and vulnerable. As Montanans, we are all bearing witness to the final decline of some of the last untouched ecosystems anywhere on earth. Whether we choose to see it or not, these sacred places are suffering an attack of a thousand cuts.

Recreation pressure, climate change, unprecedented land development, and a neanderthal approach to state wildlife management are collectively contributing to an ecological decline we all see and feel. When conservationists raise their voices about a particular user group, it isn’t personal. They are sharing incontrovertible truths that however inconvenient will impact everyone. As mountain bikers, it is our responsibility to think about more than our own trails, our own user experience on public lands, and our own anthropocentric sense of privilege to face the systemic implications of our actions.

Whether you are a mountain biker, a skeptical conservationist, or a stakeholder embroiled in a similar debate over some other public land user group, you likely carry with you some level of dissonance between the anthropocentric and ecocentric perspectives on the issue at hand. As a mountain biker and a conservationist, I feel conflicted about how the sport I love is impacting wildlife. And, whoever you are, you should feel conflicted too. In the same way that wrestling with our inner demons benefits our personal relationships, reckoning with the incongruence between our conservation virtues and our behavior in the outdoors will help us have a more reciprocal relationship with those rarefied phenomena that make Montana so special: wilderness and wildlife.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Thank you for reading Calvin Servheen’s thought-provoking personal essay. We hope it provided plenty of fodder for self-reflection and discussion. Before you go, Yellowstonian invites you to view the video below. The footage was shot by a mountain biker using Go-Pro camera and posted on youtube. The rider boasts of rapidly descending Blackmore Peak in the Gallatin Mountains of Greater Yellowstone near Bozeman, dropping 3500 feet in elevation over a span of six miles. We ask you to consider these parting questions: 1. What might be the reaction of a mother grizzly with cubs or a cow moose and calf to a single or multiple riders traveling at this high rate speed down a trail? 2. How many riders would it take for the wildlife to abandon the area? 3. If a rider is keeping one’s attention laser focused on the trail in front of them, to make sure they don’t run into a tree or boulder, how would their response time be to the sudden appearance of wildlife or humans especially while moving fast and quiet around blind turns? 4. Given the rapid rise in number of mountain bike riders and the ongoing proliferation of user-created and illegal trail building, how much have land managers like the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management seriously assessed the impacts of mountain biking, and other forms of mechanized recreation such as e-bikes, motorcycles and ATVs? 5. Why haven’t more mainstream conservation organizations, purporting to be advocates for wildlife conservation, called for more intensive analysis of the cumulative effects of all outdoor recreation and what the impacts will be as number of users grows?