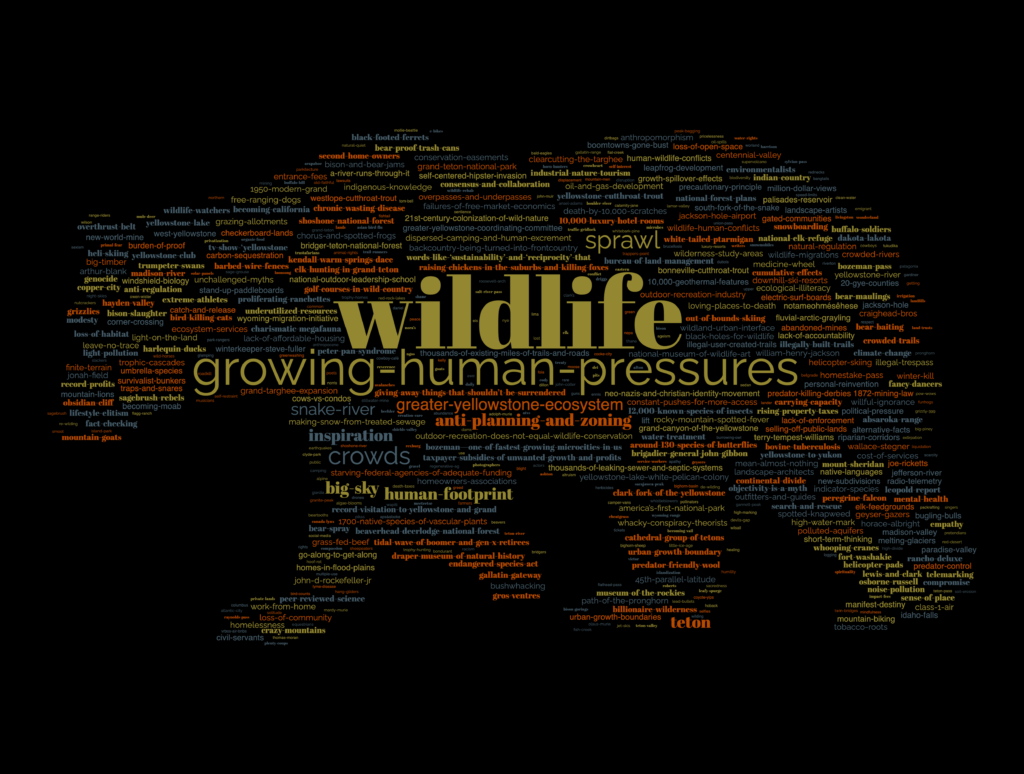

EDITOR’S NOTE: in the last commentary from professional independent planner Randy Carpenter and national planning authority Robert Liberty, they noted that Park County, Montana is losing rural open space at a per capita rate 40 times larger than in adjacent Gallatin County. According to Gallatin Valley Land Trust Executive Director Chet Work, Gallatin County is losing its remaining undeveloped open spaces, working lands and wildlife habitat at a rate of two acres for every acre protected. Today, Gallatin County, which encompasses Bozeman, Belgrade and part of Big Sky is a symbol in Greater Yellowstone—and the state of Montana—for how not to approach hyper-growth issues. Below is the first of three pieces in a series written by journalist and Yellowstonian co-founder Todd Wilkinson examining how growth is affecting Greater Yellowstone’s world-class wildlife and the implications for Park County and other valleys. —Gus O’Keefe, Yellowstonian co-founder

Does Wildlife Matter To You?

by Todd Wilkinson

Today, no matter where you live, ask your friends and family this question: does perpetuating the survival of wildlife matter?

It’s not difficult to predict what the response will be, especially if you are here and a reader of Yellowstonian. We trust in your values. But essential now is to present a follow up question, and have it go something like this: in order to protect wildlife, and accommodate its persistence amongst us, ask next what are people willing to do to help make wildlife preservation happen?

Very likely you may get a blank stare in return and this is one of the reasons why ecosystem protection, of the kind essential to safeguarding the living hallmarks of Greater Yellowstone, isn’t happening at the scale it needs to.

In late May, the landscape conservation advocacy group, Yellowstone to Yukon, shared the results of a “groundbreaking study” published in the journal Conservation Biology and co-authored by its president and chief scientist Jodi Hilty.

Here are three of the most noteworthy findings:

About 50 percent of mountain lands worldwide are heavily impacted by human activities — more than previously thought.

Up to 40 percent of mountain ecosystems are degraded by fragmentation (i.e., landscapes broken up by human activity, especially sprawl, commercial development and industrial activities).

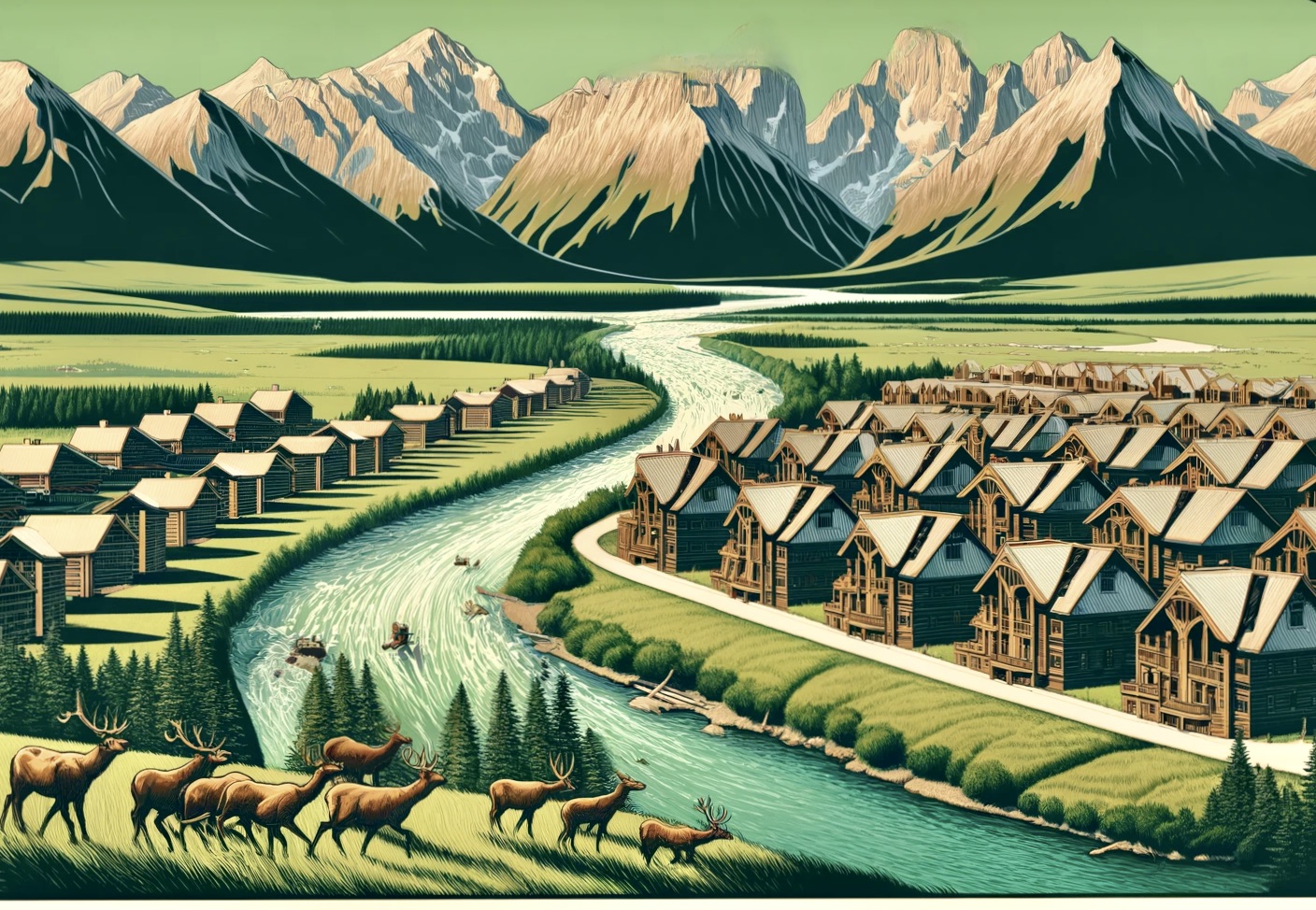

The Yellowstone to Yukon region is the most intact but least protected mountain region of all of them. Only 15.6 percent of the Y2Y region, with the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem representing its most visible segment, is protected. Greater Yellowstone still has all of the species that were present on its landscapes in 1492, the year Europeans arrived on the continent. And much of that is owed to its former geographic remoteness, low human population and large amount of public land.

But today, it’s the accelerating pace of human development on private lands, plus the rising number of additional permanent and season residents pouring in on top of fragmentation which presently exists, that threatens to transform Greater Yellowstone from being a beacon of wild landscapes and re-wilding into a 21st century emblem of de-wilding.

There is no other wildlife-rich ecosystem like Greater Yellowstone in the Lower 48, and no other ecosystem has retained high wildlife values in the absence of thoughtful planning and zoning on private land. The notion that protection can be accomplished solely through free-market economics, or voluntary conservation measures adopted by developers or wishful thinking is a myth. Why? Because that has been the predominant conservation strategy to date and it is now failing.

As has been noted by scientists, more than 80 percent of the species in Greater Yellowstone—mammals, birds, and others—depend on healthy private lands for all or part of their survival.

The best and simplest way to insure that the unprecedented bounty and array of wildlife species in this bioregion persists is to manage its landscapes as if wildlife matters. Of the 20 counties in Greater Yellowstone, most county commissions and planning staffs have treated this challenge more as an afterthought or burden than a priority. Why? Because most have no competency in thinking about natural systems; that’s not a dig, it’s a fact.

There is no other wildlife-rich ecosystem like Greater Yellowstone in the Lower 48, and no other ecosystem has retained high wildlife values in the absence of thoughtful planning and zoning on private land. The notion that protection can be accomplished solely through free-market economics or voluntary conservation measures adopted by developers or wishful thinking is a myth. Why? Because that has been the predominant conservation strategy to date and it is now failing.

Numerous studies confirm that, in recent decades, the expansive Greater Yellowstone region and other valleys in the Northern Rockies have permanently lost huge swaths of open space and functional, secure habitat on private lands and the projections are it will continue at a faster rate if the same approaches continue.

Right now in Greater Yellowstone, amid the 20 counties and 50 towns of any size, there is just one designated job position—in the town of Jackson, Wyoming—devoted to gauging the effects of private land growth on ecology but even that individual is burdened by other responsibilities.

Again, the key tools that every county has, but which are seldom employed to their potential, are thoughtful planning, enforceable zoning and policies that enable for strategic use of conservation easements (voluntarily arrangements facilitated with land trusts) with an eye directed toward anticipating more intense development pressures coming in the future.

In June, voters in Park County, Montana will be going to the polls deciding two issues: whether to approve or defeat a referendum brought by anti-regulation, private-property-rights-always-first activists that would repeal the county’s existing growth management plan. The second measure involves whether to approve an initiative that would require any county growth plan in the future to be approved by citizens at the polls, not by county commissioners whom citizens elect to represent them.

It’s a historic test, and the outcome will send a strong signal of either hope or retreat for those concerned about holding onto the things that drew them to Park County and keep them there.

Many rural corners of Greater Yellowstone are dealing with the consequences of poor planning. The irony of Park County’s ballot measure is that while its existing growth plan, years in the making, is hardly considered onerous and is generally advisory, it is the only guiding strategy the county has to deal with rural sprawl and scattershot development that is rapidly erasing vital wildlife habitat and beloved scenic views.

Many rural corners of Greater Yellowstone are dealing with the consequences of poor planning. The irony of Park County’s ballot measure is that while its existing growth plan, that was years in the making, is hardly considered onerous and is generally advisory, it is the only guiding strategy the county has to deal with rural sprawl and scattershot development that is rapidly erasing vital wildlife habitat and beloved scenic views.

There are also intensifying worries about water quality, rising taxes to pay for growth, and concerns that the pastoral character of Paradise and the Shields valleys located north of Yellowstone National Park along the course of the Yellowstone River are being lost.

More than the abstruse loom of climate change or natural resource extraction activities happening on public land, growth issues, as manifested in the ever-expanding human footprint on private lands, have been identified by prominent scientists as the most serious short-term threat to the ecological integrity of Greater Yellowstone. If decisionmakers are unable to confront these transformative changes now, much of the essence of the region, including its globally-renowned wildlife migration corridors and the health of public lands, could be impaired long before the deeper effects of climate change even arrive.

More than the abstruse loom of climate change or natural resource extraction activities happening on public land, growth issues, as manifested in the ever-expanding human footprint on private lands, have been identified by prominent scientists as the most serious short-term threat to the ecological integrity of Greater Yellowstone.

The Park County vote is perceived by many as a critical bellwether. A “No” vote retains the County’s growth policy; a “Yes” vote repeals it. Until and unless a new growth policy is adopted Montana law prevents the county from adopting zoning regulations to manage growth and development. Plenty of development, such as second homes and short-term vacation rentals, are not caused by natural population growth itself yet exert irreversible impacts on landscape and the character of communities. These lead to the question: are we building communities to serve locals or self-interested short-timers who feel little responsibility to making them better?

In fact, in recent years, the number of new homes built in Park County has surpassed the number of permanent year-round residents, which speaks to the onslaught of retirees and wealthy seasonal transplants building second homes, some of which are inhabited only a few months of the year. This is the start of a multi-part series examining what’s at stake and it will explore the consequences of short-term thinking and a place in Greater Yellowstone that is the emblem of a boomtown whose very existence is about serving the fantasies outsiders have about Montana. The issues in Park County, Montana echo in mountain towns throughout the Rockies. As an introduction to Park County, click on the (real-cool) one-minute video, below, to get oriented with its terrain, the heart of which is the Upper Yellowstone Watershed. It takes you from the front doorstep of Yellowstone National Park northward to Livingston through Paradise Valley and the wild side drainages. It’s that open space, located between the mountains, that hangs in the balance.

Next up: The Spillover Effects of Big Sky’s Ravenous Appetite For More: As Park County contemplates the future and ponders how it can protect its special sense of place, a major Big Sky land developer has moved into the neighborhood. A story about why ecologically-minded planning matters in Greater Yellowstone