For just a moment, let’s review everything we’ve been taught about how to recreate safely in grizzly bear country—the rules of which are different and more consequential than everywhere else in the Lower 48 states.

°°°°1. Carry bear spray;

°°°°2. Stay on the trail and make sure you’re making noise to alert potential bears in the area to your presence;

°°°°3. Travel in groups of four or more;

°°°°4. Whether you’re camping in the backcountry or front country, secure your food and make sure you clean up after yourself.

By and large, these recommendations have worked, helping to minimize the number of potential negative encounters between people and bruins.

Of course, when it comes to hunters heading into the mountains pursuing ungulates or anglers casting for trout along remote stretches of water in Greater Yellowstone (and other expanses of the Northern Rockies), rules number 2 and 3 are seldom observed.

Hunters and anglers pursuing skittish animals don’t make a lot of racket; they don’t stay on trails; they bushwack quietly and stealthily; and, especially in the case of hunters, they kill animals that bears eat—notably in autumn when hyperphagia spurs a physiological urge in grizzlies to pack on as many calories as possible prior to denning.

This represents a serious contradiction in how differing groups of humans orient themselves to recreating in griz country and, when it comes to big game hunting, it’s one of the reasons why there are far more hazardous surprise confrontations—including lethal ones— involving hunters and bears than hikers and other trail-based recreationists.

What the above does not consider is how human presence might be affecting wildlife without people even realizing it. With outdoor recreation, every single kind of use has impacts on wildlife. If the intensity of users is sufficiently high and disruptive enough, studies show conclusively, wildlife may stop using areas temporarily and if the uses persist, displaced animals may abandon formerly secure habitat altogether. This results in a steady, piecemeal erosion of habitat, a whittling away that may not be perceptible to people.

There’s a reason why scientists who understand the sensitivities, tolerance levels and carrying capacities of wildlife in Greater Yellowstone are concerned about rising levels of outdoor recreation use and potential expansion of outdoor recreation infrastructure onto public lands.

It’s part of a double-whammy that also includes rapidly-expanding human sprawl on rural private lands, sometimes pressing right up to the very edge of our national parks, forests, and other public lands.

Wildlife is being squeezed in obvious and subtle ways. Secure, optimal habitat is not only finite, but it’s shrinking fast and the most worrisome part is it’s happening dramatically in the crucial between-spaces of public land and the galloping suburbs, permanently impacting such things as migration corridors and vital winter range.

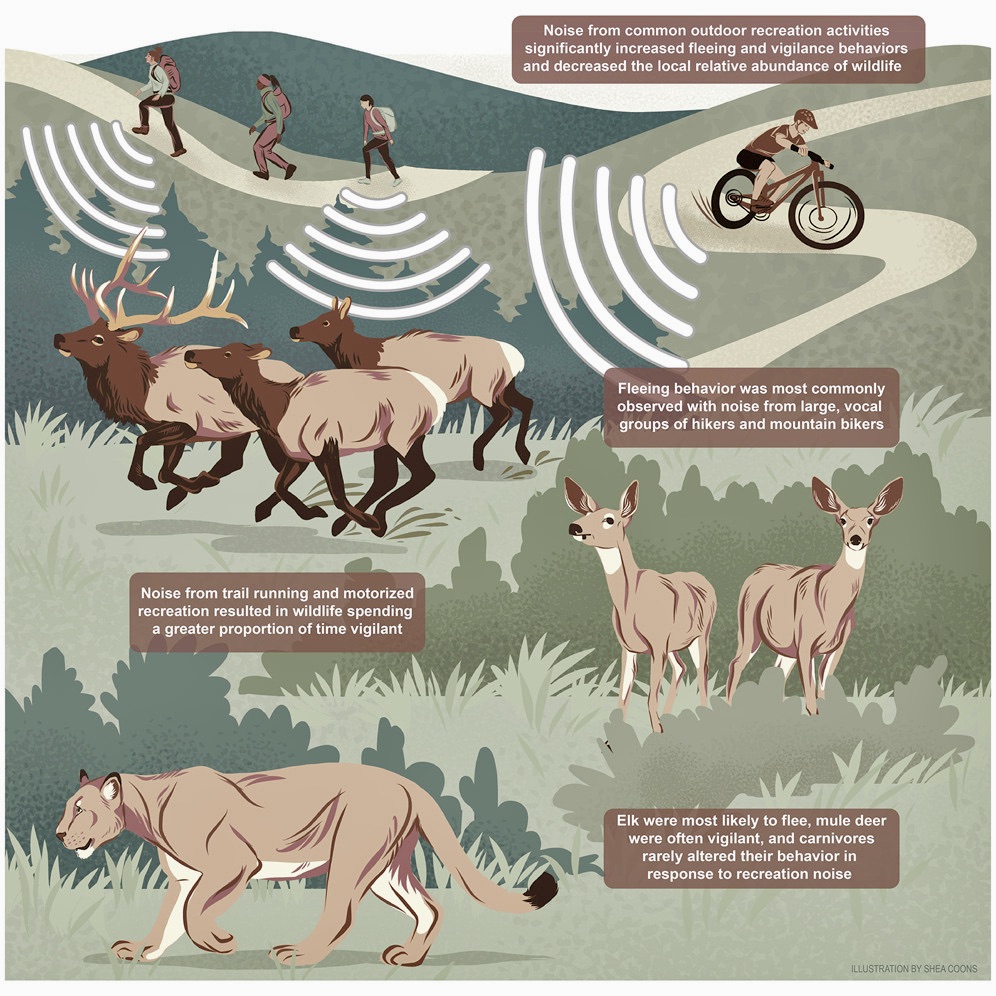

“Noise from larger groups of vocal hikers and mountain bikers caused the highest probability of fleeing (6–8 times more likely to flee).”

Regarding recreation on public lands, there’s a new peer-reviewed scientific paper, based in Greater Yellowstone and written by Katherine A. Zeller and four other authors. Titled “Experimental recreationist noise alters behavior and space use of wildlife,” it appeared this month in the journal Current Biology.

The gist is this: “Noise from larger groups of vocal hikers and mountain bikers caused the highest probability of [wildlife] fleeing,” they write.

In fact, the authors note, animals were six to eight times more likely to flee from noises associated with those activities than from sounds associated with a motorized forms of recreational noise.

This isn’t a condemnation of humans nor of outdoor recreation. It is instead yet another empirical reminder that many of the most important emerging wildlife conservation threats involve not how wildlife need to be managed, but we humans.

In particular, if society wishes to hang onto the diversity and abundance of species that exist in Greater Yellowstone and nowhere else in the Lower 48, public land managers need to better consider the needs of wildlife in consensus and collaboration discussions. To date, most consensus and collaboration efforts have given priority to serving the desires of human stakeholders—the vast majority of whom are outdoor recreationists constantly pressing for more access.

At times, outdoor recreation user groups have joined forces with some Greater Yellowstone conservation organizations to argue for less land protected as wilderness because, even though it would benefit wildlife, it would exclude their favored outdoor recreation activity.

The public is awakening to the fact that those same conservation organizations continue to peddle a myth that outdoor recreation equals better wildlife conservation outcomes when there is a growing mound of countervailing evidence.

Perhaps the biggest looming question is: are we human recreationists able to empathize with how wildlife on the ground is interpreting our unprecedented and sometimes chaotic invasion of us entering their space?

The study, mentioned above, took place on the Bridger-Teton National Forest, which encircles the eastern and southern flanks of Jackson Hole. Along with Bozeman, Big Sky, and the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, Jackson Hole has the most intense levels of outdoor recreation use in Greater Yellowstone. Pressures on public lands are growing from a combination of short-term visitors and a rising population of local residents.

“Providing outdoor recreational opportunities to people and protecting wildlife are dual goals of many land managers. However, recreation is associated with negative effects on wildlife, ranging from increased stress hormones [in animals] to shifts in habitat use to lowered reproductive success,” the authors of the study write. “Noise from recreational activities can be far reaching and have similar negative effects on wildlife, yet the impacts of these auditory encounters are less studied and are often unobservable.”

Noise? Yes, just noise alone.

The researchers wanted to see if they could measure cause-and-effect between human disturbance caused by noise and the response of wildlife. To gauge impact, the team installed remote cameras and speakers on wildlife trails in the study area on the B-T. When animals entered the area, their movements triggered speakers to broadcast differing types of noise and then cameras positioned nearby chronicled animal behavioral response. The noises were broadcast for just 90 seconds.

The kinds of noises projected from the speakers were, variously, those associated with hiking, mountain biking and off-highway vehicles. Noises were tiered to mimic groups of differing sizes, with and without human voices. From this, researchers were able to observe not only immediate flight responses but how wildlife presence changed afterward, i.e. did the animals return to the places they were?

The observed species were elk, moose, mule deer, red fox, black bears, wolves, cougars, coyotes, and pronghorn antelope. The speakers and cameras were activated by the movements of those animals 1,000 times.

“Elk were the most sensitive species to recreation noise, and large carnivores were the least sensitive,” the authors write. “Our findings indicate that recreation noise alone caused anti-predator responses in wildlife, and as outdoor recreation continues to increase in popularity and geographic extent, noise from recreation may result in degraded or indirect wildlife habitat loss.”

“Elk were the most sensitive species to recreation noise, and large carnivores were the least sensitive. Our findings indicate that recreation noise alone caused anti-predator responses in wildlife, and as outdoor recreation continues to increase in popularity and geographic extent, noise from recreation may result in degraded or indirect wildlife habitat loss.”

The Forest Service wrote in a statement which coincided with the study’s release: “This new science calls into question whether otherwise high-quality habitat truly provides refugia for wildlife when recreationists are present and underscores the challenges land managers face in balancing outdoor recreational opportunities with wildlife conservation.”

Lead author Zeller added, “Our study is the first to quantify responses to human-produced recreation noise based on recreation type, group size, group vocalizations, and wildlife species. Information like this can help managers balance recreation opportunities with wildlife management, which is critical as outdoor recreation continues to grow in popularity.”

With no offense to Zeller and colleagues, a follow up question for the researchers would be to clarify the meaning of “balance” within the context of what, and, again, is it more a matter of managing people or wildlife?

No one in the Forest Service wants to mention a word that is treated as taboo—limiting human access to places that represent the highest and best wildlife habitat that remains in an ecosystem that is the last of its kind still standing because human wants and desires have tipped the scale of balance in our favor practically everywhere else. This at a time when the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management are readying to spend billions of dollars in the coming decades vastly expanding access into wild country, at the behest of the outdoor recreation industry whose appetite for blazing new trails and expanding markets for new products seems insatiable.

But at what cost to the rarest kind of wildness?

In a release from the Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station ecologist Dr. Mark Ditmer, a co-principal investigator and co-author of the study, said, “Our findings highlight the need for thoughtful planning, with potential consideration of noise mitigation measures to minimize the impact on wildlife while still providing outdoor recreational opportunities for people.”

Ditmer added, “Noise from recreation can carry far beyond a trail system, so understanding how noise alone can affect wildlife is important for management.”

Is he suggesting that people shouldn’t make noise in Greater Yellowstone griz country? That doesn’t always work out so well for hunters? And can’t some wildlife smell us even if they don’t see or hear us? The issue at hand isn’t a noise issue; it’s a volume of humans issue and if we apply the same model of public land use that exists in Moab we’re going to lose our wildlife.

The cumulative impacts of outdoor recreation already have led to conflicts among user groups on many public lands in the West and an increasingly frustrated public. Dispersed recreation is only leaving more places filled up. The Forest Service seems to believe that the answer to congestion is to simply greenlight more trails and capitulate to renegade outdoor recreationists who are creating illegal trails without enforcement or penalty.

The effects of rising pressures on wildlife brought by recreationists, with and without dogs, already is a concern in areas like Teton Pass, and Cache Creek at the edge of the town of Jackson, and, in northern areas of Greater Yellowstone, the Bridger Range and northern Gallatins near Bozeman, as well as public lands surrounding Big Sky.

Researchers with the Bridger-Teton study, besides referencing hikers and mountain bikers, added this synopsis: “We found wildlife were 3.1 to 4.7 times more likely to flee and were vigilant for 2.2 to 3.0 times longer upon hearing recreation noise compared with controls (natural sounds and no noise),” they wrote. “Wildlife abundance at our sampling arrays was 1.5 times lower the week following recreation noise deployments.”

“We found wildlife were 3.1 to 4.7 times more likely to flee and were vigilant for 2.2 to 3.0 times longer upon hearing recreation noise compared with controls (natural sounds and no noise). Wildlife abundance at our sampling arrays was 1.5 times lower the week following recreation noise deployments.”

What are the implications of this? What has it meant for wildlife where levels of outdoor recreation have already risen and the presumption from land management agencies was of it being benign? What does it portend for national forests like the Custer-Gallatin where forest officials opted to, in place of seeking more habitat protected as wilderness that would have most benefitted wildlife, instead created new special categories of forest management that actually invite more recreation pressure?

Other studies have highlighted the negative impacts of motorized users on wildlife. Another impact, not assessed in the Bridger-Teton study, is how domestic dog presence, on leash and off, exacerbates the “flight from predator response” in ungulates (which other studies have confirmed) or how it might trigger an aggressive response from wildlife carnivores and mother animals with young offspring to the pet canines.

For good reason, the recreating public might be confused by the proliferation of mixed messaging coming from federal land management agencies, the outdoor recreation industry (whose rhetoric suggests impacts on wildlife do not exist) and some conservation organizations.

One may wonder: where is the leadership for wildlife conservation that once existed as a hallmark of the environmental movement in Greater Yellowstone?

As this study provides only a simple snapshot in time and space, how can—and will— its results be received and extrapolated? To date, there has never been a professional, independent comprehensive analysis that pulls together all of the available scientific studies on wildlife displacement (there is a significant number out there) and correlates them specifically to recreation-caused impacts in Greater Yellowstone—not only as they exist now, but what will they be with user trends headed nowhere else, but up.

Support Yellowstonian and

Get Some Real Cool Visual Stuff

From now through the end of July, Livingston-based Artemis Institute, the parent non profit entity of Yellowstonian, is participating in the Park County, Montana Community Foundation’s Give a Hoot fundraiser and all contributions made to Artemis Institute will support Yellowstonian‘s mission of providing conservation journalism focused on Greater Yellowstone. We would be profoundly grateful for your support and here’s your chance to get a really cool visual reward for your generosity: Anyone who contributes $35 or more will receive their pick of one individual species poster below or all three for $100. For a donation of $350 or more, supporters will receive a special, limited-edition collector’s lithograph that features all three of Greater Yellowstone’ species’s icons. It is hand-signed by Eric Junker.