by Todd Wilkinson

Yes, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is renowned in the Lower 48 for its “charismatic megafauna”—i.e. big, obvious animals recognized for their size, hooves, horns, antlers, claws and canid teeth. As a bioregion, it holds a concentration of large mammal species that has persisted continuously in the wild since the end of the last Ice Age. More recently, over the last 150 years, these animals survived waves of de-wilding that pushed many to the brink of disappearing while eliminating several from much of their former ranges.

In healthy, diverse ecosystems every species fills an important niche, and their natural history tells a story.

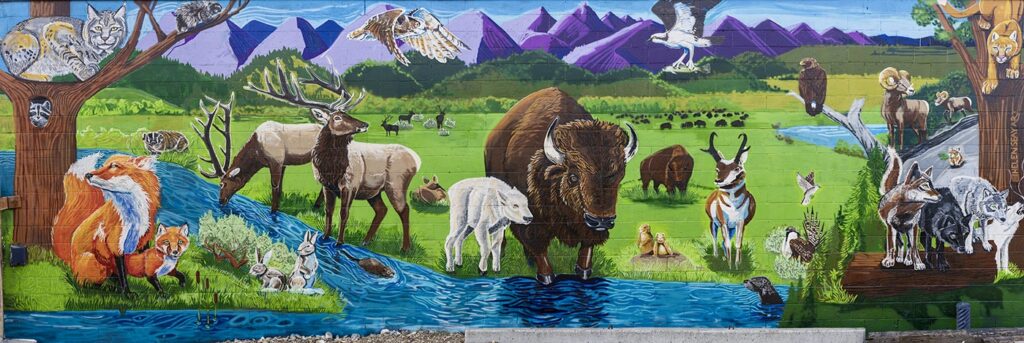

Let us begin this series of WildJourneys, based on Helen Seay’s engaging mural in downtown Jackson. We’ll commence by paying homage not to an obvious giant—but to one who inhabits the artwork’s walls more discretely and maintains a subtle presence the same as its profile in our wild backyard.

Though it dwells in the shadows of prominent icons, emitting vocalizations that make it a pipsqueak, look closely at the mural and you’ll find Ochotona princeps (Latin for the mighty pika).

It’s easy to mistake pikas for rodents, since they bear a similarity in appearance to mice and rats, but they actually hail from the same family as rabbits and hares. To some who cannot grasp nuance, singing their praise may elicit a yawn. But pikas are worth our full consideration as underdogs coping with planetary change—similar to polar bears in the Far North whose perseverance could be negatively affected by winnowing Artic Sea ice. Pikas also are examples of persistence—introducing us to a term called adaptive capacity—in the face of forces altering their habitat.

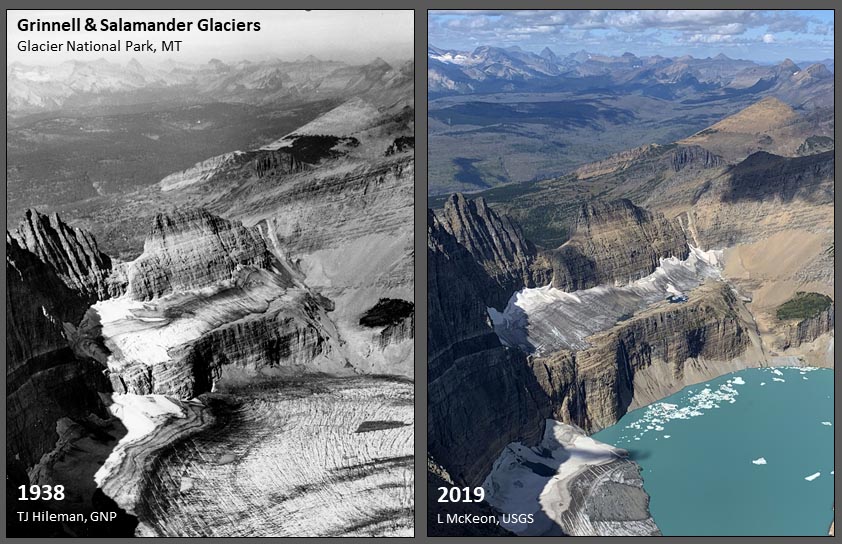

Climate change can be difficult sometimes for we humans to wrap our minds around. Scientists have described pikas as indicators, in that their fate may portend the future of other species in Greater Yellowstone and the mountainous West. They are counted among snow-dependent species like wolverines, Canada lynx (which depend upon snowshoe hares), whitebark pine, white-tailed ptarmigan and even fluvial Arctic grayling. What affects them also has implications for pollinators such as butterflies, bees and bats, that play a vital role in the survival of native plants and crops.

In a brand new year, we’ll start on an ironic cheery note about a dreary pronouncement pertaining to pikas that’s been put into wide circulation. The pronouncement is this: that without protection and help, American pikas could be the first species in the West to be a casualty of climate change.

Extinction of a species, through inattention, neglect or willful action, is a heavy word that few enlightened generations of humans with a conscience would want to have it happen on their watch. Martha the (now stuffed) passenger pigeon who died on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoo was the very last of her species, which numbered in the billions.

Different species of pikas (there is no exact population count) occur in northern latitude mountainous environments around the world, but the one found in Greater Yellowstone is O. princeps. For many years, researcher Dr. Andrew T. Smith has been studying them and is one of the deans of pika research. In a comprehensive overview of pika conservation that appeared in the Journal of Mammalogy in December 2020, Smith addressed the litany of doomsday predictions for the species. “At an earlier time, I have made similar claims myself. The problem with these statements is that they are not consistent with the evidence that I have presented.”

Pikas have pelage which makes it difficult for them to “thermoregulate” their internal body temperature, i.e. stay cool enough to not overheat in summer or freeze to death from bitter cold in winter. Their habitat, talus slopes and jumbles of rock, provide shelter from heat and cold, with snow offering critical insulation from the latter.

Dr. Erik Beever, a longtime pika researcher with the USGS Northern Rockies Research Center in Bozeman, is a specialist in “disturbance ecology.” He has been lead or co-author of several peer-reviewed scientific journal articles. When it comes to pikas in Greater Yellowstone, having snow is the most consequential and potentially limiting resource but persistence of pika subpopulations, inhabiting actively used habitat patches, goes beyond variables of what we see when we enter the backcountry for fun.

When it comes to pikas in Greater Yellowstone, having snow is the most consequential and potentially limiting resource but persistence of pika subpopulations, inhabiting actively used habitat patches, goes beyond variables of what we see when we enter the backcountry for fun.

While average annual global temperatures are clearly warming up, Smith acknowledges in his overview that he, too, contributed to the narrative that pikas could be climate change’s first faunal victim. In Greater Yellowstone, this would hold huge significance because it means pikas would be the ecosystem’s first loss of a species larger than insects in 500 years.

(Here, an astute reader may ask, well, what about wolves? Indeed, Canis lupus was deliberately extirpated as a viable population in Greater Yellowstone by the 1930s due to relentless predator eradication campaigns carried out by states and the federal government—including, it should be noted, by park officials inside Yellowstone. Wolves were reintroduced to Greater Yellowstone during the winter of 1995 and today this ecosystem is the only one south of Canada with its full complement of wild species that was present on the landscape in 1491, before Europeans arrived in North America. As amazing and rare as that is—and why it’s a theme of Seay’s mural— it’s also worth asking why does it stand alone in that regard)?

In 2007 and 2016, wildlife advocates petitioned to have pikas given federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, based largely on concerns about climate change, yet in both cases the US Fish and Wildlife Service determined that it was not warranted. This raises two questions: is it better to have pikas listed or not, and, depending on the answer, what tangible actions can be taken to protect them?

In his paper, Smith takes readers on a geographic tour across the West where pikas have been studied and were known to occur—from the mountains of the Rockies to jumbles of volcanic lava flows at Craters of the Moon in Idaho to old hardrock mining ore dumps in California.

Paleontological evidence suggests pikas were once more widely distributed and appeared in talus and boulder areas at a variety of elevations but have disappeared, more often at lower altitudes. The good news, Smith wrote, is that pikas, especially in remote montane settings with regular snowfall with not a lot of disturbance from human activity, populations are holding their own.

A bright spot, as Greater Yellowstone pika researcher Beever notes, is Grand Teton National Park and the montane public environs of Jackson Hole, which is why Seay’s inclusion of a pika invites our reflection. Here’s link to Wyoming Game and Fish’s results of a recent monitoring effort to identify where pikas are in the state.

A bright spot, as Greater Yellowstone pika researcher Beever notes, is Grand Teton National Park and the montane public environs of Jackson Hole, which is why Seay’s inclusion of a pika invites our reflection.

Individual pikas tend to live three to four years. They are not a threat to anything else—not livestock, the safety of humans or pets, and they’re not dinner fare for people either. They do not hibernate like grizzly and black bears. They are active all year and when the high country is blanketed by snow, they move short distances through the subnivean realm often via tunnels in snow and passageways amid the talus. Snow not only helps to keep the mountains cooler and moister deeper into summer—it also aids the growth of vegetation pikas eat.

In their living quarters pikas cache “haypiles” of vegetation that sustain them through winter. Ermine and marten are the most formidable natural hunters of pikas, along with coyotes, owls, eagles and hawks. There is some inferred evidence, cited in a number of research papers, that pikas at low elevations were negatively impacted by intense livestock grazing, humans shooting them and alterations of habitat.

An analysis, published in November 2024, focused on the Southern Rockies but holds implications for the Northern Rockies. Appearing in the journal Ecolography, it confirms the role snowpack plays and how the ability of pikas to move shapes their adaptive capacity. In a paper published in 2023, in Biological Conservation, Beever and 20 co-authors explored how adaptive capacity can be used to gauge persistence prospects of differing sentinel species that might serve, metaphorically as canaries in the coal mine. They looked at pikas and four other small mountainous mammals.

“Our major finding is that, broadly, American pikas appear to have notably lower adaptive capacity relative to other montane mammal species also considered vulnerable to climate change to varying degrees (e.g., the yellow-bellied marmot, bushy-tailed woodrat, and [projected-less-vulnerable] golden-mantled ground squirrel), and far lower adaptive capacity than the ubiquitous deer mouse.”

The National Park Service has an ongoing research program called Pikas in Peril that initially focused on pika populations in eight different parks, including Grand Teton, Yellowstone and Craters of the Moon. As the Park Service research noted, “Habitat connectivity and barriers to animal dispersal and gene flow emerged as key drivers of vulnerability, mediating the impacts of increasing temperatures and altered rain and snowfall. In some parks with expanses of mountain boulder fields and lava flow habitats, high habitat connectivity may offset the stresses of climate change and allow pikas to persist.”

In other words, if pikas exist not as vast interconnected metapopulations, but mostly in smallish, isolated subpopulations and they cannot move to find hospitable alternative habitat as conditions change, they are more vulnerable to disappearing and, as a 2015 research paper in Global Change Biology notes, concerns about diminished genetic diversity. It noted that species distribution models used to describe species niches can actually fail to predict the future effects of environmental change. It made a strong case for the importance of on the ground field work.

In his status report, researcher Smith stated, “The trait that puts pikas most at risk from climate change is their poor dispersal capability. Dispersal is best understood as the ability of pikas to overcome a behavioral–physiological barrier; in hotter environments dispersal is more restricted than in cooler core pika habitat. In terms of current pika biogeography, small sites at low elevation that are extirpated for whatever reason are less likely to be recolonized.”

Along with the term that Beever and colleagues employed—adaptive capacity—Smith adds another: vagility. He notes that “the vagility of pikas may be more directly related to climate change than any other factor. It is no surprise, therefore, that the model variable that often explained pika site persistence better than temperature among historic sites was the amount of talus upslope—a measure of connectivity.”

Vagility speaks to the ability of an organism to move and/or migrate, and it figures into the well-being of most species in Greater Yellowstone, from ungulates to pikas, amphibians and insects like army cutwork moths that dwell in distant farm valleys then head, by the billions, into the mountains, gather in scree, are sustained by drinking the nectar of mountain wildflowers and then are themselves feasted upon by grizzlies to put on weight in the months before denning. Climate can imperil that food web, and it is negatively affecting whitebark pine trees, that grow best in cold conditions and produce seeds in their cones that are consumed by grizzlies, Clark’s nutcrackers and red squirrels. Warmer temperatures left whitepark pine more stressed and vulnerable to attack by mountain pine beetles, blister rust and dry conditions spawning wildfires.

In Climate-Changed World, Past Habitat Not Always Prelude To Future Needs

By extension and extrapolation, what scientists are saying is keeping species alive in the future will not depend solely on protecting areas where they have occurred in the past or are now but anticipating where they might need to go and securing that habitat before it is lost. This is why, in the case of larger animals—ungulates and predators that move between high and low country—loss of undeveloped private lands and working ranches can be so problematic.

For pikas, vagility means they can hightail to other places when habitat conditions become unfavorable. In another joint-author study in which Beever advised the ambitious work of a then graduate student, Peter Billman, over 760 talus areas were ambitiously surveyed in four different mountain ranges in Montana and Idaho. Each of the mountain ranges had roughly 16 watersheds. Billman and colleagues systematically walked up each drainage, from lower to higher talus areas, and grouped what they found into three categories: did they find any evidence of pika presence in talus where they might be; did they find evidence of previous pika occupation based on the presence of distinctive clues of pika fecal pellets that can last for decades; and did they find active subpopulations.

They found that pikas had disappeared from roughly a third of patches where they had been, but the disappearance rate falls to roughly 10 percent if adjusted to focus primarily on higher elevation talus where conditions were snowier and cooler. This means the high mountains are serving as refugia.

Pikas are not long-distance travelers like mule deer or pronghorn. Fascinating is that in one instance there was evidence that when pikas naturally moved from one patch to another, they covered about 279 meters in elevation or around 900 feet (the equivalent of three football fields end to end) which is a huge trek. In addition to their populations being sensitive to temperature extremes, individuals are prone to stress. In one experimental attempt at translocation, Beever told me, five of six pikas that were captured and moved died within hours.

One of the wildcards often discussed within the community of pikas researchers is rate of average temperature rise in the years and decades to come. An accelerated rise could temper the consensus that the panic button need not be pushed now.

Smith noted in his analysis that “the narrative that pikas are going extinct, supported by a restricted and somewhat compromised data set at the margins of the species’ range, appears to be an overreach. All available evidence shows that pikas are doing well across most of their range, but that there are limited, low-elevation losses in some marginal pika habitats.” Extirpation, some scientists say, would move up mountains with rising temperatures.

Landscape fragmentation threatens vagility and at lower elevations the main cause is human. According to Dr. Cathy Whitlock, a Greater Yellowstone-based ecologist and authority on climate change, persistence for many species in the future will depend on creating resilient spaces that not only serve as buffers against ecological disturbance such as drought, fires, sprawl, and other human pressures such as displacement from intensifying levels of outdoor recreation, but secure habitats that may serve as de-facto refuges. Whitlock was a lead author of the Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment published in 2021.

Dr. Cathy Whitlock, a Greater Yellowstone-based ecologist and authority on climate change, says persistence for many species in the future will depend on creating resilient spaces that not only serve as buffers against ecological disturbance such as drought, fires, sprawl, and other human pressures such as displacement from intensifying levels of outdoor recreation, but secure habitats that may serve as de-facto refuges.

The authors of the Billington-Beever paper et al conclude, “Many species are likely to continue shifting their distributions to track cooler and wetter climates in the face of contemporary climate change. However, a more mechanistic understanding of how, why, and to what extent climate change affects range limits is still strongly needed,” they write. “Understanding how environmental stressors vary across multiple range margins is fundamental for a more holistic understanding of climate influences on species range dynamics. Here, we have provided widespread evidence of recent range retractions of American pikas at their range core in North America, primarily driven by higher temperatures in both summer and winter.”

This is not to say pikas are not threatened by climate change, even inside protected areas. In Utah, they have been extirpated from Zion National Park and yet, nearby, according to Beever, they maintain variable and sometimes tenuous occupancy at Cedar Breaks National Monument.

Here, an aside: pikas in eight of 10 western states are classified as a species of greatest conservation need. The two states where they are not, inexplicably, are Montana and Idaho. That has implications because the classification qualifies states to receive vital research dollars to continue monitoring. According to scientists, studying pikas, on a dollar per data basis, is between 100 and 1000 times less expensive than studying Canada lynx or wolverines which are incredibly elusive and exist at low population densities.

Besides, studying pikas can yield exhilarating discoveries involving life stories on individuals, the same as with grizzlies or wolves. Based on the Montana Natural History Program model, 84 percent of pika habitat in the state occurs on federal public land, two percent each on state land and private land under conservation easement and 12 percent on tribal or other land.

Meet the Dark Lord

In Greater Yellowstone, one researcher who took on studying pikas as an area of special interest is April Craighead, co-founder of Craighead Institute in Bozeman with her husband, Lance. While it wasn’t highly known by the public, April identified the equivalent of a white buffalo in a pika population in Montana’s Gallatin Canyon southwest of Bozeman.

Some might also find it interesting to know that Lance is part of the legendary Craighead family led by the late twin brothers John and Frank Craighead. They were Jackson Hole-based researchers best known for their pioneering work tracking of grizzly bears using radio collars and the clan also has a legacy of studying birds of prey. Not long ago, Craighead Beringia South, based in Jackson Hole and headed by Lance’s cousin, Derek Craighead, completed important studies on exposure of raptors to lead poisoning caused by birds ingesting lead ammunition in the carcasses of deer, elk and moose shot by hunters. Craighead Beringia South operated for 23 years and Derek Craighead said of the role of scientists: “I believe that research biologists should be a voice for the animals they study; an advocate for their survival and co-existence.”

Lance is brother to Jackson-based Charlie Craighead who in 2025 is set to debut a film on how water effects ecology in Wyoming.

In 2021, April Craighead authored a report titled The pikas of Gallatin Canyon after a decade of research and she delivered the findings of her report to a sold-out public event at REI in Bozeman. It shows how interested denizens around southwest Montana are in climate change and pikas.

This project is an extension of the work that Dr. Chris Ray began in 1998 with pikas at Emerald Lake in the Gallatin Mountains south of Bozeman. Craighead began to wonder if pikas at lower elevations were still extant and how temperatures differ for these pikas at lower elevations. Within two years, she and a team of agency field personnel and citizen scientists had mapped 139 new pika locations on top of 44 active sites. She turned particular focus to the Gallatin Canyon.

Since 2010, occupation of pikas there was identified through a survey of multiple pika territory sites. Of 22 recorded, three had a minimum of six years of occupancy and one had 11 years of continuous residency. Craighead noted that pikas have definite preferences for where they establish home ranges. “The high occupancy rates indicate that these are preferred territories and even if a territory is vacant for a few years it is highly probable that a pika will inhabit it again,” she observed.

As Craighead was doing her field work, she happened upon something that seized her attention, a rare black-haired pika, “a dominant male,” that she nicknamed “the Dark Lord.” News of it spread quickly throughout the world of eccentric pika researchers and earned her a place in scientific literature. Similar to wolves, genetic variability can yield melanistic traits in pikas, too, giving them a blackish coat compared than their common tannish-brown-gray color phase. They have other pelage hues, too.

For obvious reasons, Craighead did not circulate the sighting on social media, and it would not have been in the best interest of her study subjects to have a crowd of curious pika groupies descended on them. The Dark Lord already faced a serious existential challenge. “Most of the time, these variant colors are detrimental to pikas since they tend to stand out on the talus and become more noticeable to predators,” Craighead wrote in her report.

For obvious reasons, Craighead did not circulate the sighting on social media, and it would not have been in the best interest of her study subjects to have a crowd of curious pika groupies descended on them. The Dark Lord already faced a serious existential challenge. “Most of the time, these variant colors are detrimental to pikas since they tend to stand out on the talus and become more noticeable to predators,” Craighead wrote in her report.

In 2013, Craighead and Chris Ray successfully live-trapped the Dark Lord and did some blood work, revealing it had elevated levels of glucocorticoid correlating to higher levels of stress. One behavioral nuance is that the Black Lord was observed spending a higher percentage of time on the surface of talus than other pikas. He survived until late summer 2015. None of the Dark Lord’s offspring in his bloodline have yet demonstrated, in appearance, the recessive gene that favors melanism.

Pikas, Craighead’s research shows, inhabit talus on both sides of the north to south lining Gallatin Canyon, a fact likely oblivious to millions of human motorists traveling the busy road. Craighead observed pikas crossing US Highway 191 (which is a journey fraught with peril for pikas and many species) but she’s unsure if pikas are capable of crossing the Gallatin River or would use a wildlife overpass or underpass.

In their own investigations separate from Craighead’s, Beever and co-authors note is that the outlook for pika persistence has not adequately assessed the prospects of pikas being able to re-inhabit higher-elevation areas from which they have vanished, but it could be promising. Some of those places might actually be conducive to translocation if necessitated by climate change.

Sometimes it’s easy to work ourselves into lathers of dread and paralysis. We think the world is coming to an end and there’s nothing we can do about it. So many of us have retreated into personal isolation. The recent Covid and election years, combined with social media replacing real face-to-face community, seems to drive this on a collective level.

Thinking about pikas in the here and now can deliver a sense of relief and help restore wonder. Perhaps as you move through the mountain talus where pikas congregate, in the rafters of Greater Yellowstone and other high elevation areas of the West, you’ll greet them with gratitude for opening our minds—to better appreciate animals that cause us to pause and look closer.

Things you can do to benefit pikas

Become familiar with their natural history, terrain they are likely to inhabit and presence by buying a field guide;

When camping, be aware that talus is habitat and if pikas are there make camp away from their homes. If they appear in talus, sit quietly and watch;

Control your dog. It might be entertaining for you to watch your pup chasing wildlife, but it is stressful, unethical to allow your pet to harass public wildlife and can be deadly for wild creatures.

Pikas are amazing living sentient beings and not objects for target practice. Plus, it’s incredibly stupid to be firing your weapons at rock piles.

Support government agency investment in wildlife research and efforts to halt the spread of cheatgrass that outcompetes native plants pikas and other wildlife eat

Support conservation and research organizations, including journalism sites that give you stories like this.

ALSO READ AS PART OF THE WU/YELLOWSTONIAN SERIES: