by Todd Wilkinson

As anyone who has studied human history knows—and, obviously, everyone should—our kind has been on the move since long before we evolved into a species. Common ancestors were borne in the Eden of Africa and then spread around the world. Motivated by more than exploring new places simply for fun or adventure, which, after all, may in the modern world be the ultimate form of indulgence, most set out to find better places, where the living was easier and safer, and where sufficient resources could be harnessed or appropriated to perpetuate survival.

This is what all species do; they move, humans included—the more mobile the species, with greater access to more safe secure habitat, the more resilient they are, and the better they fare.

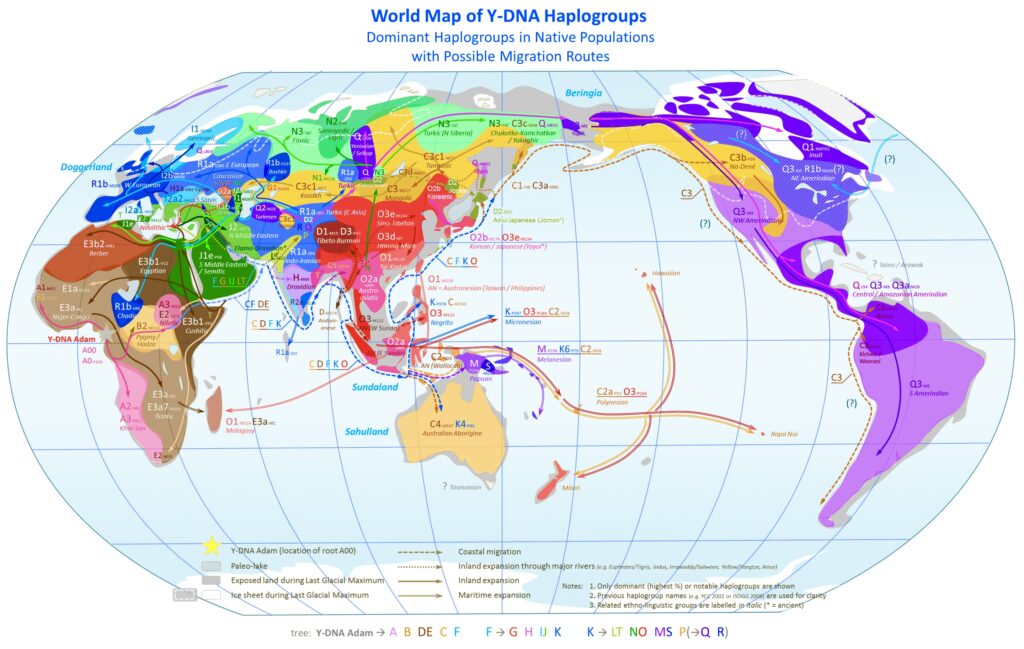

The record of Homo sapiens’ peregrinations is written in genes (see map at bottom), and in the rise and fall of great civilizations, many of which collapsed. Factors determining failure often relate to what the late William Catton called “overshoot,”—i.e. humans imposing demands on a setting that exceed the limits of carrying capacity in delivering things—resources—necessary to sustain stable populations.

This applies to humans as well as other species. The clear record of disappearance happening to the latter because of various kinds of consumption, willful elimination and habitat loss caused by the former (us) is undeniable. The record is written in history and land. Far from being cemented in place or frozen in time, even local indigeneity possesses fluidity when viewed across time and space.

Often, people get caught in semantical traps or play games with words. For instance, some treat the word “immigration” as an entity different from “intra-migration”—one connoting humans moving across an international border and the other applying to humans packing up and resettling in other parts of the same country. In the US, since the end of World War II, there has been a formidable and, in recent years, growing intra-migration of retirees and workers moving from largely northern climes to states in the snow-free Sun Belt. Today, downsides of the demographic shift, in Florida, California and Arizona, are visibly manifest in daunting ecological impacts as well as perennial concerns of property damage owed to ocean storm surges or just the opposite in the desert—deepening water deficits driven by unsustainable growth.

Mountain settings in the West—the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies, the western face of the Wasatch surrounding Salt Lake City, and western and eastern sides of the Sierra-Nevada—are grappling with major sprawl issues, including homes built in forested areas vulnerable to suffering billions of dollars’ worth annually of property damage—and potential loss of human life—to wildfire. Meanwhile, the Great Salt Lake and its renowned bird estuaries are literally dying, and in the megalopolis that is Greater Denver, its celebrated nature of place is being crushed under the tentacles of a human anthill colossus.

The Covid years catalyzed a newer form of intra-migration, this one involving people fleeing areas they perceive to be overcrowded or blighted, and the ability to work remotely, and retirees flocking to new areas. There is also evidence of environmental/climate refugees moving away from areas prone to natural disasters and difficulty getting insurance, excessive heat, and social-political factors. Environmental refugees, evermore, figure into the narratives of many international immigration issues. Almost a century ago, during the drought-filled Dust Bowl years, humans from the Southern Plains emigrated in mass—over 300,000—to California.

___________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________

A 21st century accelerant has been social media and TV melodramas popularizing the scenery like Yellowstone. Soon, the vulnerable Madison Valley of Montana will also have a bead drawn on it when the same producers unveil their Yellowstone spinoff, The Madison. Read landscape ecologist and wildlife migration policy expert Dr. Arthur Middleton’s recent op-ed about the Yellowstone TV-show-factor in The New York Times.

In each of the US environs mentioned above, human pressure has not only displaced native wildlife but the permanent footprint of development has resulted in less human tolerance for some species, foreclosing upon the possibility of them ever being brought back. Look no further than the current controversy over reintroduced gray wolves in Colorado. No area in the US in modern times has ever preserved its wild or natural character in the absence of planning and zoning, certainly not where anti-government, anti-regulation and so-called forces of the free market, driven by real estate speculation and developers, have dominated decision-making.

Real estate in the Northern Rockies is fueling an intensifying bonanza. In place of mining titans, timber and cattle barons flexing their political power, it is now outside capital investment firms buying, trading and developing private land, exploiting lax planning and zoning regulations in local counties. But for whom and at what cost to nature is the material prosperity benefitting?

In many cases, their profits are being at least partially subsidized by citizens who are paying higher taxes to foot the bill for costs associated with added necessary public services—roads, law enforcement, water, sewer, fire departments and medical services—that developments need to function. The cumulative effects are also bringing subtle and not-so-subtle tolls on wildlife.

There is a fact most people on the streets of Greater Yellowstone who value wildlife don’t consider: the greatest aggregate threat to wildlife and the integrity of public lands is private land development being manifested in the form of one word: sprawl. It’s growing and isn’t going away.

For several months, Yellowstonian has worked in collaboration with a veteran large landscape conservation scientist and policy experts from NumbersUSA to produce a new and unprecedented study that addresses the ecological impacts of sprawl on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. As an overview, nothing like this has existed before. Click here to read the executive summary or here to find the foreword that lays out an overview, or, here, you can download a pdf of the entire 235-page study. Why should this be of regional and national interest? All one needs to do is mention this place name: Yellowstone National Park.

Greater Yellowstone, the bioregion that has the country’s first national park as its heart, is the only one remaining in the Lower 48 states with all of its native mammal, avian, aquatic and other species that were present here in 1491, the year before Europeans arrived on the continent. Most of its larger mammals were earlier pushed to the edge of annihilation in the latter half of the 19th century by human killing of those species combined with habitat loss related to agriculture and development. But the advent of conservation measures enabled species to recover and many have for the last quarter century.

Keys to Greater Yellowstone’s enigmatic distinction have been its relative geographic isolation, abundance of public lands that accommodated species, low human population, and the presence of working farms, ranches and undeveloped private lands that protected habitat and allowed wildlife to move and thrive. Land fragmentation in other regions and wildlife relegated to small islands of habitat caused many species to disappear. That phenomenon in high growth areas also inhibits the ability of farmers and ranchers to persist.

The presence of wildlife in Greater Yellowstone is the anchor to a multi-billion-dollar annual nature-tourism industry; it is paradoxically why people are relocating and visiting here in record numbers; and it too has a finite carrying capacity in danger of approaching overshoot. Technology does not engineer fixes to the overshoot of sprawl, nor, for that matter, is erecting expensive wildlife overpasses and underpasses a quick fix to habitat destruction.

In a recent short documentary on growth issues in southwest Montana, Bozeman Mayor-elect Joey Morrison, a Millennial who grew up in Miles City, Montana in a single-parent household, offered this observation. “Montana is an extremely developer-friendly state. Almost all of our land use laws are written by and for the development community. And, consequently with this increase in land value, the only people who are happy about it are developers and lenders.” The same could be said of nearly every corner of Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies.

Today, Greater Yellowstone’s world-class wildlife is facing an existential threat as three of the factors above—geographic isolation, low human population, and abundance of ag and undeveloped private lands—no longer exist and along with the positive synergies they created. While the public land base hasn’t winnowed and though climate change already is bringing dramatic ecological shifts mostly related to water, there is a fact most people on the streets of Greater Yellowstone and who value wildlife don’t consider: the greatest aggregate threat to wildlife and the integrity of public lands is private land development being manifested in the form of one word: sprawl. It’s growing and isn’t going away.

For now anyway, federal public lands are safeguarded by a gauntlet of laws put on the books by subsequent generations of both Republicans and Democrats working together in Congress. Private lands, however, are being governed with no such protection and few major development proposals related to exurban sprawl are subjected to vigorous environmental review with guaranteed public involvement the way, say, a proposed hardrock mine on public lands would be.

Sprawl-related factors—buildings, roads, food attractants, bulging accompanying zones of human intolerance, loss of natural lands, domestic dogs roaming off leash etc.—represent the biggest emerging and expanding cause of conflicts between humans and grizzly bears. Independent scientists say it jeopardizes their biological recovery and has been highlighted for years, but it isn’t being factored into the metrics assessed by politicians for delisting the species.

In Greater Yellowstone, one fourth of the 23-million-acre ecosystem is comprised of private land and that ground represents crucial interstitial spaces for how grizzlies and other wildlife navigate the landscape. (Note: ranchers have demonstrated far greater adeptness at co-existing with grizzlies and other wildlife on their land than exurban settlers replacing them. As most conservation biologists say, condos are not better than cows if the goal is sustaining wildlife in Greater Yellowstone.

What’s at stake?

Those same factors of sprawl imperiling bears are the single biggest menace to the viability of Greater Yellowstone’s globally famous wildlife migrations. In addition, lack of a cohesive strategy in counties and states for dealing with proliferating individual water and septic systems looms as a major concern about the quality and abundance of underground aquifers and water quality in streams. These things have implications for hunters and anglers and the guiding industries. A less realized offshoot is how sprawl increases the potential for over-tourism—causing a backlash in many corners of the globe.

Nearly all of the 20 counties in the three-state area of Greater Yellowstone have no comprehensive plan that assesses the cumulative impacts of sprawl on ecology, water, air quality, wildlife, tax rates (which are rising to pay for services), lack of affordable housing, and loss of community. In a region touted as an emblem of “ecosystem thinking,” there is no large landscape vision that transcends boundaries. Elected officials, in fact, have fiercely resisted zoning, treating it as a topic of taboo.

Voluntary conservation measures, particularly within the context of counties and towns having no comprehensive plan or permanent ecologists on staff advising them about the short and long term consequences of development decisions, are clearly failing, wildlife experts say. Further, consensus and collaboration efforts are obviously well intentioned but slow-moving, time-consuming, easy to derail, and conflict averse. They, too, have failed to achieve land protection at scale and with outcomes that counterbalance the rapid amount of natural lands being destroyed or impaired by compromise.

As a study by Headwaters Economics illuminates, Montana had 381,294 homes in 2021 and 31 percent were built since the year 2000. During that time, the state lost one million additional acres of open space—an area equal in size to Glacier National Park— but the negative ecological impacts on wildlife and sense of place are exponential greater. In recent decades, 56 percent of new homes have been built outside the existing municipal boundaries of cities and towns. Notably, those statistics do not include the explosion in growth that accompanied Covid.

Beyond what already has been fragmented or protected by conservation easements, estimates from the heads of some local land trusts are that for every acre protected, at least two are being lost to sprawl forever. Poll after poll, across the ideological spectrum, confirm that local people are not happy with the pace of change and frustrated by how it is being engaged.

Lack of enforceable planning and zoning as a means for confronting sprawl is not a strategy for dealing with unwanted sprawl and the public being forced to subsidize the profits of developers, experts interviewed for this series say.

Albert Einstein never said (by the way) that “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results,” but it doesn’t take a genius driving through the high-growth valleys of the Northern Rockies to know lack of planning has not been brilliant tactical maneuvering.

Confronting sprawl also does not depend on who is president in The White House nor which political party holds power in Congress, the governor’s mansion or state legislatures. It begins locally with becoming knowledgeable about sprawl. Action must not be based on false, wishful reasoning, or developers claiming that undoing regulations inside existing cities will fix the problems beyond them because there is no evidence in Greater Yellowstone that it has. They are only interested in more development, not saving nature, because if they were, this ecoregion would not be at the crucial point of inflection it’s in now. Examples abound of where the free market and, dare one say, greed, have only exacerbated the problem.

Confronting sprawl does not depend on who is president in The White House nor which political party holds power in Congress, the governor’s mansion or state legislatures. It begins locally with becoming knowledgeable about sprawl. Action must not be based on false wishful reasoning or, worse, denial.

Our intent is that it become a common reference point and tool for advancing a larger discussion about the obvious impacts of sprawl. We hope it prompts deeper reflection by local elected officials and planning staffs, state lawmakers who write codes that shape and in some cases, have hobbled the ability of local governments to implement commonsense land use policies, and federal and state land and wildlife management agencies dealing with the ripple effects of sprawl that are registering just beyond and within their jurisdictional domain.

Until the scope of sprawl is realized by the public and elected officials citizens elect or have representing their interests, it is impossible to contemplate solutions, which is a main objective of Yellowstonian’s ongoing series on sprawl.

Over the years, NumbersUSA has produced several other studies that mostly analyze the impacts—economic, social and landscape (open space) costs of sprawl on states, and it also has done a bioregional study focused on the states and counties surrounding Chesapeake Bay which has wrestled with serious water quality issues affected millions of people as well as farmers, a seafood and recreation industry. Never before has an analysis focused on wildlife—and it is wildlife, more than any other natural wonder, that speaks to the larger essence of Greater Yellowstone in terms of bolstering local identity and giving it a prominent place in the world.

As a public service to our readers, we are allowing you to download a free Executive Summary and Foreword written by me after years of writing about growth issues. This represents Part 3 of a series that was begun earlier in 2024 and will continue going forward. It is ur objective that this series provide an impetus for exploring possible solutions, as the status quo—as growth issues being approached only piecemeal or not at all—is clearly causing rapid transformation of the natural character of region that has the best known natural protected area in the world—Yellowstone. Of course, all of this comes down to a simple question: does maintaining the last great concentration of native wildlife in the American Lower 48 matter?

————————––––—————————————————––––––––

Dispersal of Homo sapiens: Humans have always been on the move but modern population shifts can have profound implications for the last remaining concentrations of wildlife which depend upon unfragmented landscapes. For context, here’s a look at human movements that date back many millennia.The graphic below is a map of haplogroups, one of many, that shows movements of indigenous people based upon genetic studies of Y chromosomes. A haplogroup is a genetic classification of people who share a common ancestor and inherited genetic markers. Haplogroups are defined by a set of shared mutations or variations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) or the Y chromosome: Y chromosome: Passed from father to son. Y chromosome haplogroups trace paternal ancestry. mtDNA: Inherited from the mother. mtDNA haplogroups trace maternal ancestry. In the map, allusions to ethnic-linguistic groups are marked in italic.

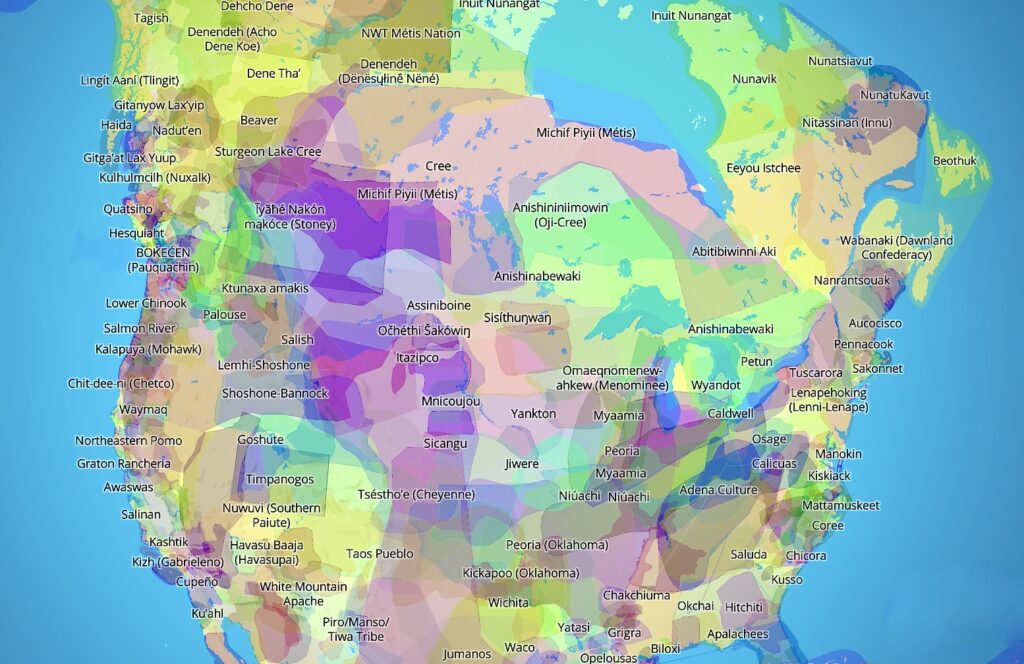

Nations among Nations: Below is the screenshot of a map created by Native Land Digital based in Canada showing the location of tribes on the continent in more recent centuries. However, if you click on the link and go to the interactive map and drag your cursor across it, you can see the differing geographies/homelands which tribes inhabit/inhabited.