by Todd Wilkinson

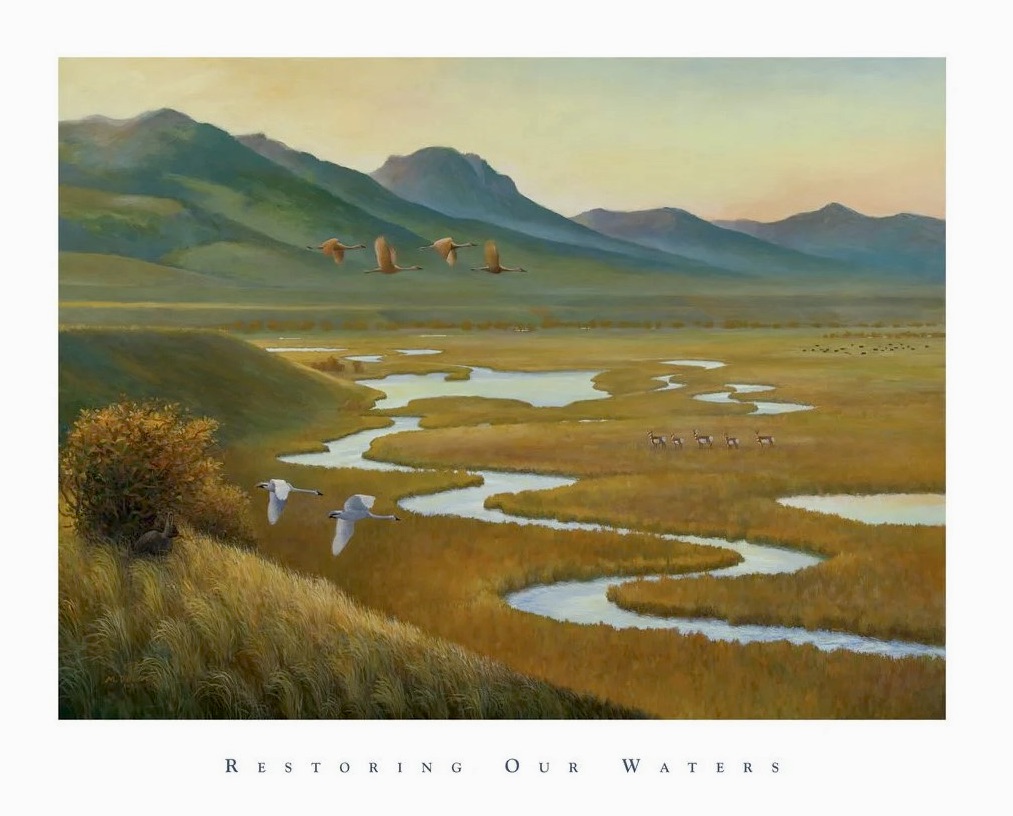

In recent decades the Upper Madison River in southwest Montana has notched millions of angler days, yet many visiting fly-fishers coming from around the world and casting into its waters may fail to realize there’s an even more incredible stream flowing through the landscape around them.

It’s possible they can’t see the land for the trout.

Why does our society purport to regard rivers with sacred reverence, but often we do not extend the same level of admiration to rare corridors of terra firma, which accommodate the movement of terrestrial wildlife holding far more biodiversity—and have existed just as long—as those waterways?

Why is it sacrilege, for example, to dam a public stream, preventing it from being free flowing, but it isn’t heretical to erect a “dam” across a world-class wildlife passageway, killing it with carelessly-placed residential subdivisions?

Does a company or holder of private property have the right to knowingly destroy some of the rarest natural treasures that belong to the public? In beholding a bigger picture, what represents the confluence of common sense and the common good?

These questions loom large today in the Madison Valley, and they should cause reflection in other valleys too.

Why is it sacrilege to dam a public stream, preventing it from being free flowing, but it isn’t heretical to erect a “dam” across a world-class wildlife passageway, killing it with carelessly-placed residential subdivisions? Does a company or holder of private property have the right to knowingly destroy some of the rarest natural treasures that belong to the public?

To stand alone in the middle of the Madison, and then, to pivot panoramically—like a spinning water-efficient sprinkler wetting a crop of alfalfa in summer—evokes feelings that literally can take the breath away.

Urban dwellers who have never been to this corner of the inner West might have a difficult time putting into words what they are encountering; more than a few city slickers who orient their wayfinding only by identifying human landmarks might feel uncomfortable, or become lost, or mistakenly call the Madison “empty” of things that should otherwise matter.

For even longtime locals who are tuned in, it’s possible these days to feel a mix of euphoria and disorienting vertigo. No matter how many times you’ve been to the Madison, a defining impression comes from confronting so much open space, uncluttered in a way that is rapidly ceasing to exist in the nearby eastern Gallatin Valley surrounding Bozeman.

Beyond first impressions, were one to have a second, it might take the form of an epiphany; the realization that so much of the private ground covering the valley floor in the Madison has been protected—deliberately, voluntarily and in perpetuity— through conservation easements brokered between organizations such as the Montana Land Reliance, Nature Conservancy, Trust for Public Land and Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation along with legacy- and heritage-minded ranchers who know how special their dale is.

To accentuate this point, there are more major clustered easements here than anywhere else in Montana.

This, then, leads to a third impression, a sensation of pure wonderment, upon learning how many thousands of native animals— elk, pronghorn, mule deer, whitetails, moose and other species, including carnivores like grizzlies, wolves, wolverines, mountain lions and smaller creatures—still move across the Madison’s vast peneplain, often in close proximity to cattle herds.

The pronghorn migration corridor in the Madison is the second longest known to exist in the world while the number of moving wapiti, some heading seasonally in and out of Yellowstone National Park many miles to the east, is one of the largest in the ecosystem. They don’t all move en masse; a better allusion is drift of animals, diffuse and discrete, though no less remarkable.

A final impression is a realization, call it a jolting discovery, liable to make the heart sink if one values the status of Greater Yellowstone as a national natural treasure. Involving ecological function, it is the reality that so much of what one sees is actually a figment—a half-empty, half-full glimpse at what was, and has been, but may not still be around in the soon to be metaphorical tomorrow. Today, there’s uncertainty and panic among those tracking accelerating change and the fact that Madison County really has no game plan in place for dealing with an onslaught of people who want to claim a piece of it for themselves.

In Greater Yellowstone, other valleys are dealing with wake up calls about growth now in various stages of reckoning.

In Paradise Valley, Montana, which stretches north from the front door to Yellowstone Park to Livingston, locals received a reminder of why planned growth and zoning is important. Recently, a landowner who owns property in a beautiful side drainage to Paradise Valley, Suce Creek, announced he was selling to outside developers who have grand plans for 100 luxury staycation cabins. Because there’s no codified regs due to the success of anti-zoning zealots, there’s little Park County elected officials and administrators can do to stop it. One county commissioner called it just the tip of the iceberg, a prelude to what is coming. Today, Park County can no longer afford to maintain all of its rural roads.

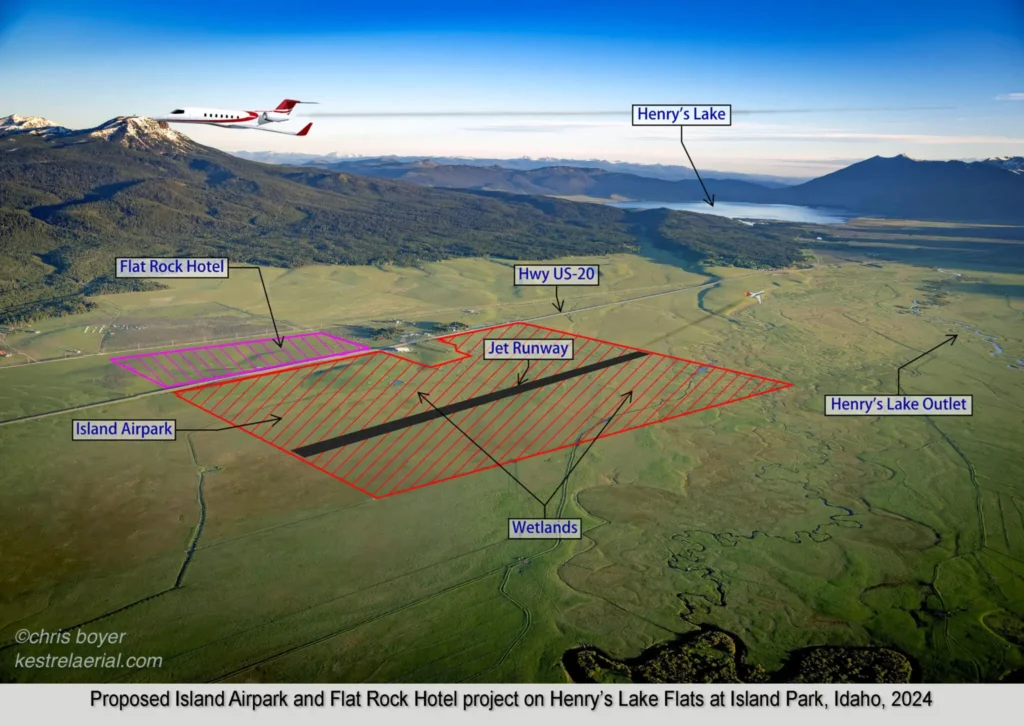

In Island Park, Idaho, near a nationally-recognized piece of private ground protected by the Nature Conservancy and which safeguards a wildlife migration corridor for species flowing in and out of Yellowstone, developers have proposed a three-story Marriot Hotel and private residential airpark on Henrys Lake Flats enabling wealthy vacationers to fly in on their private planes. The project has met with a huge outpouring of public resistance that is matched by rhetoric from developers who say they ought to do whatever they please on private land.

In southern Jackson Hole, Teton County, Wyoming commissioners earlier this year approved a new 1,437-unit subdivision, supposedly to address affordable housing, but many are skeptical it will accomplish its mission. What’s certain is that the giant footprint it exacts will only exacerbate deepening growth-related issues, including loss of wildlife habitat and epic traffic congestion problems. County commissioner Luther Propst, who cast the lone vote of dissent in a 4-1 approval, called it “the single worst land management decision in the history of Teton County.”

To the west of Jackson Hole, on the other side of Teton Pass, county commissioners in Teton County, Idaho, along with the US Forest Service and concerned citizens are confronting expansion of Grand Targhee Resort. Not only are they concerned about the physical impacts on public and private land, but that it will serve as a magnet for a lot more investment capital pouring into the valley. Teton Valley already is coping with spillover effects of growth from Jackson Hole but corners of the valley are also resembling the frenzy that turned Big Sky into a development colossus.

Cindy Riegel served 10 years on the Teton County, Idaho Commission and became its chair, but she was surprisingly defeated this year in her re-election bid when a PAC poured money into an 11th-hour messaging blitz. She attracted the ire of realtors, builders and developers by trying to champion planned growth, wanting to help Teton County, Idaho avoid the deepening growth pains plaguing Teton County, Wyoming where she lived before. “I know the vast majority of people in our community don’t want sprawl, but we have an obvious group of minority voices who are all about making as much money as possible off of the beauty and nature of this place as fast as they can,” she said in an interview. “It’s really hard to fight against. People are afraid to speak up and bullies are beating them down. I’m appalled we’re letting individual developers get away with what they are in our valley. Yes, we have codes and zoning but nobody wants to follow the rules any more.”

I know the vast majority of people in our community don’t want sprawl, but we have an obvious group of minority voices who are all about making as much money as possible off of the beauty and nature of this place as fast as they can. It’s really hard to fight against. People are afraid to speak up and bullies are beating them down. I’m appalled we’re letting individual developers get away with what they are in our valley.

Outgoing Teton County, Idaho Commission Chair Cindy Riegel

And then there’s Big Sky in the Madison Range, saddled into drainages feeding the main stem of the Gallatin River and already causing epic loss of habitat and displacement of wildlife. Major property owners boast that the complex of mostly luxury hotels, trophy homes and condos selling for $1 million each is only at 60 percent of build out. An executive for one of the biggest players, Lone Mountain Land Company, not long ago spoke to concerns being raised about growth impacts relating to groundwater, wildlife, water quality threats to the Gallatin River and traffic on US Highway 191. He claimed Big Sky was engaged in holistic thinking. “Some might call these challenges growing pains,” he said, and then caused the jaws of many to drop with what he uttered next. “But it’s a lack of growth that hurts…we’re committed to developing a future that’s in harmony with the beauty of the land that surrounds us.”

These are but a smattering of examples.

° ° ° °

For the record, there’s not a single example in Greater Yellowstone where lack of sprawl has hurt the priceless harmony of natural beauty found in the region’s rural lands famous for their wildlife and working ranches. Despite Big Sky marketing itself as an authentic destination where “people can experience the Real Montana,” no real Montanan believes it’s true. Not there, anyway. Real Montana is a place where real Montanans still live, and where opulence and showing off are not flashed as virtues. Realness is not an invention. Real Montana still exists in the Madison Valley, and real Montanans, in a half dozen recent different opinion polls and surveys, say they want landscapes where wildlife persists and have an aversion to more luxury resorts being built to serve the fantasy indulgences of outsiders.

Pinning a new bullseye on the Madison Valley is a forthcoming spin off of Taylor Sheridan’s TV show Yellowstone. Called The Madison, the melodrama is fictionally set in that dell. If the unwanted swarm of attention, including growth pressures, brought by Yellowstone to Paradise Valley also follows suit in the Madison, many TV viewers from elsewhere, left swooned by the cinematography, may descend there too.

The Yellowstone-TV-show-effect was recently referenced in a New York Times op-ed written by the renowned landscape ecologist Dr. Arthur Middleton, best known for studying the famous wildlife migration corridors of Greater Yellowstone that are rare and unsurpassed in the Lower 48. “I see mounting development as a grave threat because of how it is carving up an ecosystem that must stay relatively intact to function,” Middleton wrote. A researcher who divides his time between the campus of Cal-Berkeley and Cody, he said voluntary conservation efforts, such as securing easements on private ranches, are not keeping pace with the amount of land being rapidly lost to sprawl on private land and he estimated that the region only has about five years to adopt a cohesive strategy to slow it down.

° ° ° °

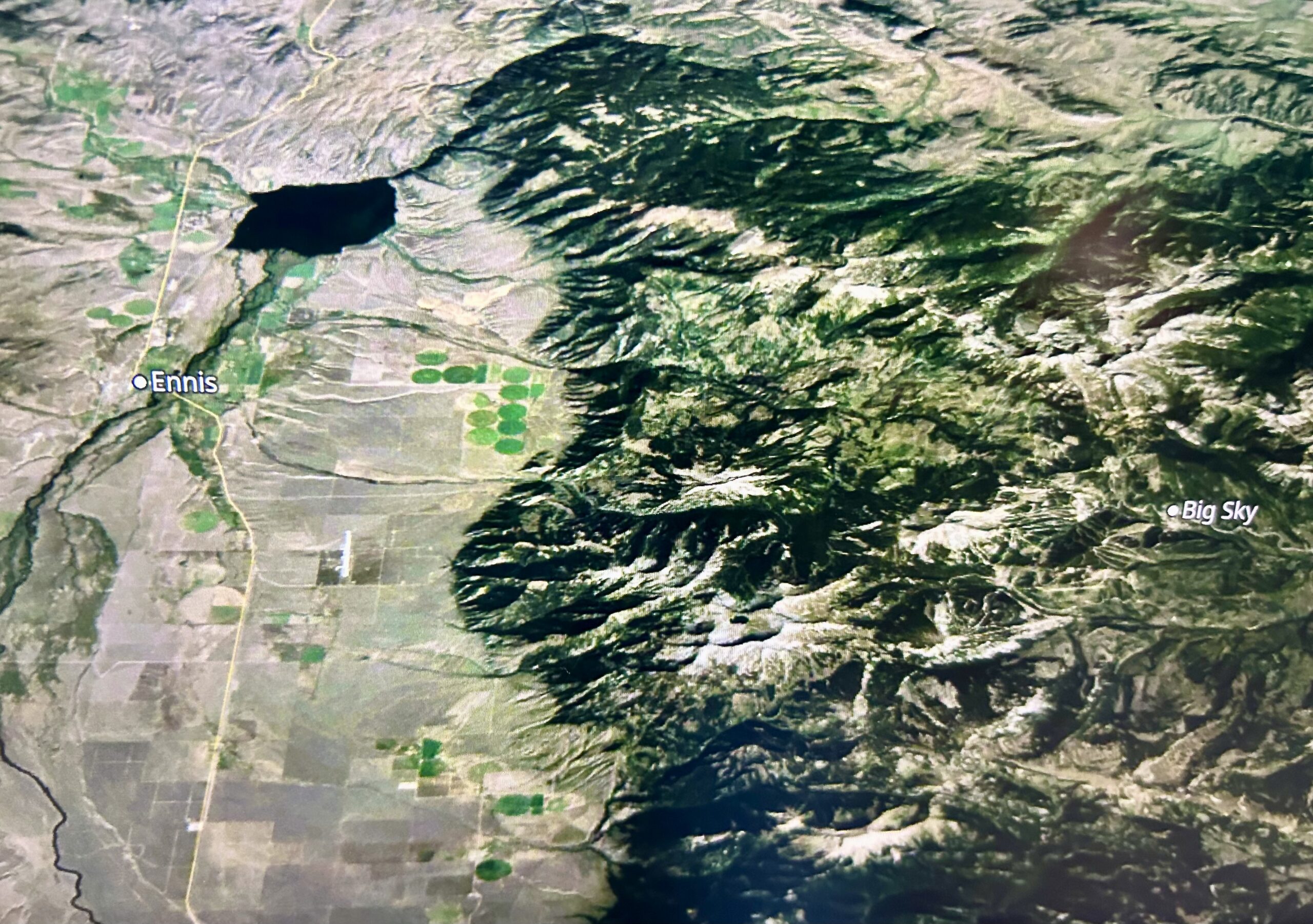

Slightly more than 50 percent, roughly 230 square miles of the Madison Valley, is protected, much of it in the form of contiguous ranchlands under conservation easement. However, hundreds of thousands of acres of unprotected ground already have been subdivided and could be developed. Generally, this pertains to a 100-mile corridor that runs down the east side of the Tobacco Root Mountains from roughly Three Forks, Montana, southward to Ennis and on to the flats around Henrys Lake in Idaho.

Conservation easements are legally enforced conditions attached to a property’s deed that restrict how much development can occur. In exchange for agreeing to these conditions, landowners receive tax breaks, not to mention being vaunted as heroes in their community.

Any conclusion one might draw from a first impression of the Greater Madison viewshed—an assumption it will always be this way—is an unreconciled illusion. Maybe “illusion” isn’t the right word, says nationally-recognized land use planner Robert Liberty who has been closely tracking the impacts of growth in Greater Yellowstone over the last decade; maybe it’s better, he notes, to call it a delusion.

The very word that could protect the Greater Madison’s nature of place is one that is almost forbidden to be uttered in almost all of Greater Yellowstone’s 20 counties, or at least contemplated. That word is zoning. In the past 50 years, according to Headwaters Economics, 51 percent of new homes in the High Divide Ecosystem were built outside of town centers in unincorporated portions of High Divide counties which includes the western part of Greater Yellowstone. Since 2010, this trend has increased and 63 percent of new homes were built outside of towns. in Jefferson and Madison Counties in Idaho, 19 percent of homes built since 2000 were built outside city limits. By contrast, in Madison County, Montana, 91 percent of new homes put up since 2000 were built outside city limits.

“There are places that acted successfully to curb rural sprawl, but I personally don’t know of any places [in America] that include a primary focus on conservation of the magnificent wildlife that gives the Greater Yellowstone region its special character,” Liberty said, noting that no attractive community has stayed that way without some kind of zoning. “How many places in North America can someone see a bison, or a grizzly or pronghorn from their yard or on their way to work? To protect that attribute, which is so incredibly rare, is your special challenge and your special responsibility.”

In autumn 2024, I wrote the foreword for an unprecedented scientific analysis on the impacts of sprawl in Greater Yellowstone assembled by conservation biologist Leon Kolankiewicz with NumbersUSA. NumbersUSA has produced a dozen and a half different sprawl studies, including one focused on the bioregion around Chesapeake Bay. Of note is that Kolankiewicz is no slouch when it comes to analyzing cause and effects of development on nature, and on budgets of local counties. Across decades, he has been enlisted by federal government agencies to draft more than 100 environmental impact statements and environmental assessments, as part of analysis mandated by the federal National Environmental Policy Act, looking at the potential consequences of major proposed developments or government actions. He’s also been a senior scientist in writing more than 40 management plans for national wildlife refuges. You can download a full digital copy of Kolankiewicz voluminous analysis of what Greater Yellowstone is facing by clicking here (available in long form and executive summary).

The most immediate cumulative threat, with negative permanent consequences for Greater Yellowstone’s iconic wildlife, is not climate change, nor natural resource extraction on public lands. It is loss of habitat rapidly happening on private land due to rural development.

The most immediate cumulative threat, with negative permanent consequences for Greater Yellowstone’s iconic wildlife, is not climate change, nor natural resource extraction on public lands. It is loss of habitat rapidly happening on private land due to rural development.

Liberty said, and Kolankiewicz agrees, that the challenge of curbing rural sprawl in Greater Yellowstone is a race against time. “There is still enough of an intact ecosystem to support large wild animals in abundance,” Liberty told me. “Many scientists and thoughtful people have described the need to plan for and protect an entire ecosystem but a real action plan for crafting and adopting land regulations at the regional scale has not been tackled. Alaska and, of course, Canada which have high natural values have this same challenge before them too, but Greater Yellowstone is the last region of its kind left in the Lower 48.”

° ° ° °

Everywhere one goes in the Madison Valley, or Paradise Valley, or the vales of the Shields and Boulder in Montana or the South and North Forks of the Shoshone River outside of Cody, Wyoming there is a shared, widespread sentiment among residents that they don’t want to go down the same path as Bozeman/Gallatin County, Big Sky or Jackson Hole.

Contrary to what cheerleaders for Big Sky say, few see it as its human footprint blending harmoniously into its setting holistically. Both Bozeman and Big Sky are emblems of what happens when there is no cohesive countywide land use plan, nor any ecologically-minded planning and enforceable zoning guiding decision-making.

Still, there’s a belief that by allowing landowners to do practically whatever they want—while touting unbridled freedom and liberty—that it will result in a different outcome from Gallatin County/Big Sky/Jackson Hole. Or, the latest ruse promoted by realtors and developers who convinced legislators in Montana to loosen regulations for land use even more, to claim that sprawl is the solution for confronting affordable housing shortages.

Press any elected county commissioner and their planning staffs in the 20 counties of Greater Yellowstone to provide evidence that laissez-faire planning based on appeasing the libertarian whims of developers results in saving the essence of their counties—as informed by the opinions of the citizens they represent—none can, because such evidence does not exist. Further, were it true, that more growth will make things better, not worse, what if the answer to affordable housing is Bozeman becoming a doppelganger of Boise or Fort Collins so that it no longer feels like it’s in Montana?

Important to point out is that many high-end private subdivisions in Montana come replete with home owners’ association regs and rigid covenants that require upkeep, and have design standards for homes down to the palette choices allowed for outside paint color as well as landscaping requirements; they are actually more restrictive, in many cases, than what would exist in countywide zoning.

It’s not that there’s been an absence of evidence staring Madison County in the face about what’s at stake. And it’s not that an alarm needs to be sounded now; it’s been blaring, scientists and iterations of conservationists say, for decades, but drowned out by a more recent land rush which has overwhelmed planning departments that were ill equipped to deal with even earlier onslaughts.

° ° ° °

Back in 2012, I was in the company of Rick Reese and Alex Diekmann, both conservationists who have since passed on. Reese was once the founding board president of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, a group he no longer believed in during the last decade of his life. He openly criticized GYC for basically abandoning its earlier regular involvement in planning and zoning issues, when it even successfully brought lawsuits to halt a proposed subdivision near Yellowstone Park that would have destroyed crucial wildlife habitat. Diekmann, meanwhile, as a representative for The Trust for Public Land, brokered several momentous private land conservation deals in Wyoming and Montana.

The three of us were entering the Madison Valley, driving over from Bozeman toward Ennis along the same old wagon train path settler John Bozeman blazed in the 1860s to deliver goods from Bozeman to mining camps in Virginia City

Descending Norris Hill and approaching McAllister near the western flanks of Ennis Lake, one is confronted with the first major trappings of sprawl in Greater Madison and they continue for a dozen miles southward toward Ennis and then west up a pass along US Highway 287 leading toward Virginian City. Passing through Ennis, a mecca for fly-fishers, and continuing southward on Highway 287, we went deeper into the middle of the Madison Valley and its signature treeless open space.

Flanking us on the west was the famous Madison River and farther beyond the Gravelly Range; to our east, the snow-capped Madison Mountains. Out of sight, but never out of our thoughts and looming just behind the Madison’s front range was Big Sky, ballooning around the feet of Lone Peak.

If speculators in Big Sky, backed by big outside money, could—but they can’t at present because of the lack of an official public access road—there is no doubt that realtors, land developers, hedge fund managers, and even sovereign wealth funds from the Arabian Peninsula, would be mining the Madison Valley for its real estate. They would also likely move to enlarge the runway of the local airport, located smack dab in the middle of a wildlife migration corridor, to accommodate private and commercial jets opening up travel from around the world.

Only a few years ago, I heard one developer refer to local government officials in Madison County as “a bunch of bumpkins” and that land there is “ripe for the pickings.” He didn’t make the offhand remark with any sensitivity or reverence for the natural wonders of the Madison Valley; flashing in his eyes was a wishful glint of making an even larger fortune, no different from the 19th century prospectors who flooded to Virginia City and left behind a wasteland of tailings. What’s preventing Big Sky from gaining major daily access in and out of the Madison Valley is that rough and tumble Jack Creek Road is private and managed by Moonlight Basin, which is owned by Lone Mountain Land Company.

On the south side of the road is a portion of 4,500-acre Jack Creek Preserve, protected under a conservation easement brokered by the Montana Land Reliance and thanks to the magnanimity of its owners Jon Fossel and Dottie Fossel. Jon Fossel is a former CEO of Oppenheimer Funds and former president and chair of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation. Montana Land Reliance has a handful of easements in the area, including 15,500 acres in Moonlight Basin.

The Montana Land Reliance has recognized not only the high ecological values of the Jack Creek drainage and its close proximity to the federal Lee Metcalf Wilderness on Forest Service land, but also the risk posed by potential additional development.

The Fossels and CrossHarbor, which purchased Moonlight in 2013 (and is the parent of Lone Mountain Land Company) have been praised for their conservation efforts, but there are others in Big Sky who, if they could, would probably love to convert Jack Creek Road into a functional back entrance accessible from the Madison Valley. The road itself is not governed by conservation easement, Montana Land Reliance told Yellowstonian.

At present, limited permission is granted by Moonlight Basin to use the road, meaning that the vast majority of Big Sky residents, visitors, and commuting workers—numbering in the thousands daily— use US Highway 191 in the Gallatin Canyon south of Bozeman. Were Jack Creek Road to become a public road, it would be a dramatic game changer in giving Big Sky direct access. This is a breathtaking reminder of how the fate of a valley like the Madison can literally turn on pivotal decisions made by a few entities or individuals and their value sets.

On the day Reese, Diekmann and I made our drive, Diekmann, in praise, ticked off the names of ranches in the Madison Valley that were protected from sprawl forever by conservation easements or had embraced other kinds of stewardship. As an example, he cited his friend Jeff Laszlo, owner of the Granger Ranches, extend across both sides of Highway 287. Diekmann praised Laszlo for his work restoring reaches of O’Dell Creek, a tributary to the Madison that provides important spawning and rearing habitat for cold water trout, as well as for a wide variety of birds. Those efforts have been lauded by the state legislature as being worthy of emulation.

Laszlo identifies ideologically as a political conservative and has served on the board of the Western Landowners Alliance whose mission is promoting sustainable, conservation-minded stewardship that gets results by offering carrots (incentives) rather than sticks (regulations perceived to be heavy handed).

Of course, by Granger Ranches having its buildings clustered, it contributes to a functional wildlife migration corridor. For full revelation, Diekmann was a dear friend of mine and Laszlo and after he died in 2016, his ashes were spread in the waters at O’Dell. (There’s also a subtle memorial marker for him at Bozeman’s Story Mill Park; it’s a simple stone with the words “Be Kind” chiseled into it).

Had Laszlo chosen to go in a different direction, he could have not put an easement on his land. He could have instead worked with a developer, lined the flanks and benchlands above O’Dell Creek with hundreds of homes arranged tidily perhaps around a championship golf course.

But he didn’t. Laszlo has told me that nature’s profundity in the Madison resides in its subtlety.

Madison County, according to the Montana Heritage Program, has 51 state-listed species of concern, consisting of 10 mammal species, 30 bird species, one amphibian species, two fish species, five insect species and three mollusk species. Meanwhile, there are 63 state-listed native plants of concern and many of those plants support an array of insects, some instrumental as pollinators crucial to the life history of flowering plants which provide forage to lots of other creatures in the food chain, including humans.

The Madison Valley holds two of three areas designated critical bird habitat areas in Madison County. Among the birds spotted in the Madison have been one of the most endangered in the country, whooping cranes, as well as Greater Sage-Grouse and migratory birds disappearing in other parts of the country, partially owed to how sprawl has destroyed habitat. Many depend on healthy wetlands fed by spring creeks and recharged by aquifers when there’s “normal” annual precipitation. But development pressure in some unprotected parts of the valley, combined with climate change bringing hotter, drier springs and summers, is creating worry not only among those who value wildlife but along ranchers and farmers.

To emphasize something alluded to earlier, the Madison Valley/Madison County is a bastion of native biodiversity, in large part because the landscape hasn’t been fragmented, carved into tiny “island” chunks of habitat that destroy migrations and cause local populations to shrink and eventually vanish as they have from the suburbs almost everywhere else. The only native large mammal missing as a free-ranging creature is bison; still, the Madison Valley has a fuller complement of native wildlife than exists in most large national parks in the West outside of the Northern Rockies.

Continuing with Diekmann and Reese on through the tiny outpost of Cameron and descending southward along US 287, we reached the point where the valley narrows closer along the Madison River. Here, a number of creeks, some with wildlife names, passed beneath the highway from the Madison Range to the east in route to the Madison River.

A few years after that trip with Diekmann and Reese, I had a conversation with Roger Lang, who a few years before had attached conservation easements to most of his 18,500-acre Sun Ranch before he sold it. Lang had made a fortune during the 1990s tech boom. He fell in love with Montana and wanted to pay forward his own good fortune. On the Sun Ranch, he advanced predator-friendly livestock grazing practices to minimize conflicts with wolves and grizzlies. He was among the first to reference the Madison as “a mini-American version of the Serengeti.” The Great Recession of 2008 extinguished his dream of getting one million private acres in the Greater Madison under easement, as much to preserve the ranching culture as safeguard wildlife.

Still owning a smaller parcel of land near US Highway 287, Lang and his wife, Lisa, have mentioned their willingness to have a potential wildlife crossing erected over or under US 287 to help reduce roadkills caused by the intersection of moving wildlife and growing numbers of inattentive motorists. “I’ve seen lines of elk, more than a thousand at a time, moving across the valley, astride of pronghorn and mule deer,” Lang said. “It is a sight you never forget.” Click on video below to get a sense of what he’s talking about.

Nearby, over at Big Sky, Tim Blixseth made a fortune by shrewdly hyper-monetizing land to create the genesis of The Yellowstone Club. Lang, had he the same inclinations, could have exploited weak planning and no zoning in Madison County, dicing and slicing the Sun Ranch into hundreds of trophy home sites and also hired retired golf pros, as Big Sky developers did, to design an 18-hole championship course on wildlife habitat and, thus, he would have compounded his investment. Take a peek at the new golf course Lone Mountain Land Company recently dug into prairie wildlife habitat at its Crazy Mountain Ranch development in the Shields Valley north of Livingston.

He chose a different path, one for which he was lauded in magazines and newspapers around the world. He once mocked the proliferation of golf course developments in Montana by saying, “You don’t travel to Montana to chase a golf ball around fake landscaping. You come to immerse yourself in the nature of this place and let it transform you rather than you trying to transform it. You can go anywhere to experience artifice. If you go to the Serengeti to see elephants and lions, you’re not taking your golf bag.”

Greater Yellowstone has been called “the cradle of American wildlife conservation.” Today, people like Laszlo, Lang and others have earned a place in the pantheon of private land conservationists here, alongside people like Ted Turner, Arthur Blank, the Rockefellers, Jon and Dottie Fossel and numerous others who have protected land in perpetuity, and the results are writ large.

Around the same time of my chat with Lang, southern Madison Valley resident Steve Primm, a friend of Lang’s, brought me to a few wildlife collision hotspots. Primm has cultivated expertise as a wildlife advocate specializing in conflict reduction between grizzlies and livestock. He also has been a volunteer with the local rural fire department and attended to his share of jarring auto wrecks and wildlife-vehicle collisions. It should also be noted that Primm and the late conservation biologist Brent Brock teamed up, applying their skillset to educating the public about the importance of working ranches and farms staying viable in thwarting sprawl.

Brock died in October 2023 from cancer at age 61, but he witnessed the inundation of new property owners to Greater Yellowstone fueled by Covid and he worried that conservation groups, who only focused on public land issues, were missing in action where their advocacy for wildlife was most needed. Again, evidence was right in front of them.

In 2006, Brock and five other scientists—Craig Groves, Andra Toivola, Tom Olenicki, Lance Craighead, and Eric Atkinson—completed a comprehensive analysis of development threats titled A Wildlife Conservation Assessment of the Madison Valley, Montana. It is, in many ways, a landmark document. Their research was based on field work and analysis by many others. The document was underwritten by the Wildlife Conservation Society, Madison Valley Ranchlands Group and Craighead Environmental Research Institute. It was an irrefutable compendium of insight that identified the valley’s wildlife superlatives.

As Kolankiewicz, who compiled the recent sprawl study on Greater Yellowstone says, “it was as fine an overview, informed by science, as you would ever want to be able to make better land management decisions.” See the roster of scientists and others who contributed research or data, below:

When one reads the report again now, superlative may, in fact, be an understatement. And it ought to forevermore disabuse the notion that elected county commissioners and aspiring developers coming into the valley are somehow unaware of what’s at stake. The authors wrote: “No areas have lost 100 percent of their diversity potential but a few areas have lost as much as 70 percent of their potential.” They highlighted Big Sky as an example of the latter. This was 18 years ago, before Big Sky ballooned into its current size and rural development, driven by Covid, initiated more creeping sprawl.

The authors added: “Areas with the greatest impact occur in the area around Big Sky…In addition, moderate degradation has occurred along the Jack Creek and North Meadow Creek drainages and within willow flats south of Ennis Lake.” They mentioned that Raynolds Pass was a priority area for maintaining wildlife connectivity and protection of winter and summer range in major foothills of the Madison Valley. They also identified the Jack Creek drainage as the most imperiled. Many species were referenced. Of impacts on rare and federally protected wolverines, an indicator species that numbers fewer than 300 in all of the Lower 48, they wrote: “The most severe degradation [of habitat] is in the Big Sky area where development associated with ski resorts overlaps high quality wolverine habitat. Extensive snowmobiling activity in the non-wilderness areas of the mountains may be causing moderate but widespread habitat degradation in the area.”

Now, nearly 20 years later, no one can deny the creep of sprawl that has ensued. Routinely, over the years, I bring up the rarefied ecological attributes of the Madison in conversations with friends in Bozeman. I’ve discussed it with hundreds of people and the most common response is, “Wow, I had no idea that something amazing like that is so close to Bozeman and I’ve never thought about that when I’m driving through the Madison Valley to fish or hike.”

Brock was also an on the ground researcher in completing a roadkill study on US 287 more than a decade ago, as a contractor for the Craighead Institute and in consultation with the Montana Department of Transportation, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Western Transportation Institute at Montana State University. The two-year study, similar to the findings of one Craighead did on Bozeman Pass, found not just a lot of animals getting struck by vehicles, but the diversity (different kinds) of large mammal species killed is greater than that which exists in 45 of the Lower 48 states. The list includes elk, moose, mule and white-tailed deer, bighorn sheep, pronghorn, grizzly bears, wolves, mountain lions, black bears, coyotes, bobcats, river otter and beaver, badgers, and even raptors feeding on carcasses. It’s possible that even imperiled wolverines and Canada lynx have been struck.

Referencing the direct correlation between land use that displaces wildlife, roads and vehicle-wildlife collisions, the report noted that the “conversion of rural lands for human housing is the most pervasive form of land use change affecting wildlife habitat in the American West….rural development significantly alters patterns of species abundance. The impacts extend well beyond the development footprint.” They noted different examples, such as the fact that elk move faster when they approach within a half mile of houses and preferred to have a one mile buffer of space separating them from development.

Here is another key take-home: Because ungulates often avoid rural developments, movement patterns can be altered as their populations decline or they avoid formerly preferred habitats by moving elsewhere. “If development blocks a migration path, then movement patterns may be significantly altered for many miles beyond development boundaries. Additionally, increased vigilance and flight [of wildlife] associated with human developments could increase the frequency of panicked animals running into traffic. Finally, habituated ungulates in developed areas may cease migratory behavior and therefore alter road crossing patterns along the traditional migration route. Simultaneously, permanent concentration of habituated ungulates near dwellings would likely create locales with increases in ungulate road crossings and increase potential for animal-vehicle collisions.”

That is exactly the scenario in the southern Gallatin Valley today with exurban sprawl outside the city limits of Bozeman overtaking winter range, creating stressed elk and animals racing through patchworks of fragmented open space, with wapiti getting fatally struck or injured by vehicles on US Highway 191 near Gallatin Gateway and elsewhere.

To further punctuate the findings of the Craighead/MTDOT study, the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, which just released a report on vehicle-wildlife collisions along nearby US 191 on the other side of the Madison Mountains, pointed to a phenomenon that also applies to US Highway 287 and other stretches. The death toll, based on visible carcass counts, grossly undercounts the number and variety of wildlife casualties.

In 2006—the same year that the benchmark scientific report, A Wildlife Conservation Assessment of the Madison Valley, Montana, was released— the American Farmland Trust ranked Madison County as the third most at risk county in all of the Rocky Mountains to loss of strategic ranchlands. The federal Natural Resources Conservation Service in 2023 released a short overview noting that there are 571 farms registered in Madison County, with an average farm size of 1,901 acres. Some 72 percent of farms are family-owned and 47 percent of the landscape is used for agriculture production. About 11 percent of those are under some form of conservation easements, which shows how much countywide is at risk of conversion to sprawl.

Subdivisions present on the land today are not going away and no one has proposed removing them. Whether wildlife persists at its present abundance in the Madison Valley will come down to what happens on the undeveloped land that remains. Subdivisions that spring up between ranches protected by easement or sit astride of them can markedly impair or undermine the ecological benefits. In fact, some unscrupulous realtors, when trying to make a sale to developers, will openly tout that an easement exists on the land next door and use it as a marketing tool for selling more lots.

Again, the threat has been known for a long time. Analysis by Mark Haggerty and a group of colleagues crunched data and found that in 2004 only Sublette County Wyoming and Park County Montana ranked ahead of Madison County at the top of 10 counties in Greater Yellowstone where ranches were being purchased as amenity buyers and developers.

Two years before that, a different study focused on biodiversity hotspots in Greater Yellowstone by noted conservation biologist Reed Noss and George Wuerthner identified the Henrys Lake/Henrys Fork of the Snake area, Gravelly-Snowcrest ranges, Red Rock Refuge/Centennial Valley, Tobacco Roots and West Yellowstone as corridors in urgent need of protection. The Raynolds Pass area is part of a crossroads between West Yellowstone, Henrys Lake, the Gravellys, Snowcrests, and Centennial Valley. Another study completed by the Resources Law Group in 2003 on behalf of the Duke, Moore and Packard Foundations identified the Madison Valley as one of two high priority areas in need of conservation planning. (In other work, Haggerty also noted that the costs of services needed for exurban development did not pay for itself in tax revenue and was causing severe economic hardship for many counties).

As mentioned in the beginning, the Madison Valley has the largest concentration of conservation easements of any valley in Montana. While the common refrain from free-market conservation organizations is to portray zoning as a taboo topic and to emphasize the use of conservation easements, those organizations can never answer this inconvenient question: what happens when large properties are sold and unscrupulous developers buy them with plans to pursue development of the kind that exists in Big Sky? What if developers don’t care if the property is located in the middle of a migration corridor and aren’t interested in securing a conservation easement?

Privately, free market conservationists do acknowledge that zoning serves a purpose not only in protecting wildlife, but safeguarding groundwater, open space and, with innovative incentives, keeping working farms and ranches on the land. But they won’t say it publicly.

° ° ° °

Raynolds Pass is a biological crossroads at a crossroad. It is novel within an ecosystem that is novel. Residing in the southern end of the Madison Valley along the border of southwest Montana and eastern Idaho, it is a thoroughfare where differing mountain ranges (the Madison, Gravelly, and Centennials) converge above different valleys (the southern Madisons to the north, Henrys Lake Flats to the south, and Centennial to the west) and the topography in turn connects to the Snowcrest and Gallatin ranges.) Running through the northern part of Raynolds Pass is the Madison River out of Quake Lake to the east.

Raynolds Pass, as numerous studies have identified, is part of a wildlife superhighway that animals have used going back to the retreat of glaciers. Even though bison were nearly wiped out in the late 19th century, and eliminated from the Centennial Valley, Bill West, former manager of Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge said buffalo trails can still be seen in the valley. Some elk and mule deer move more than a hundred miles between Yellowstone on the east and the Centennial on the west. The Centennial also is a dell where old-guard ranchers have come together with land protection groups and put properties under conservation easement. The Centennial Valley Association has quietly demonstrated how co-existence between ranching and wildlife is done on both private and public lands. https://www.centennialvalleyassociation.org/

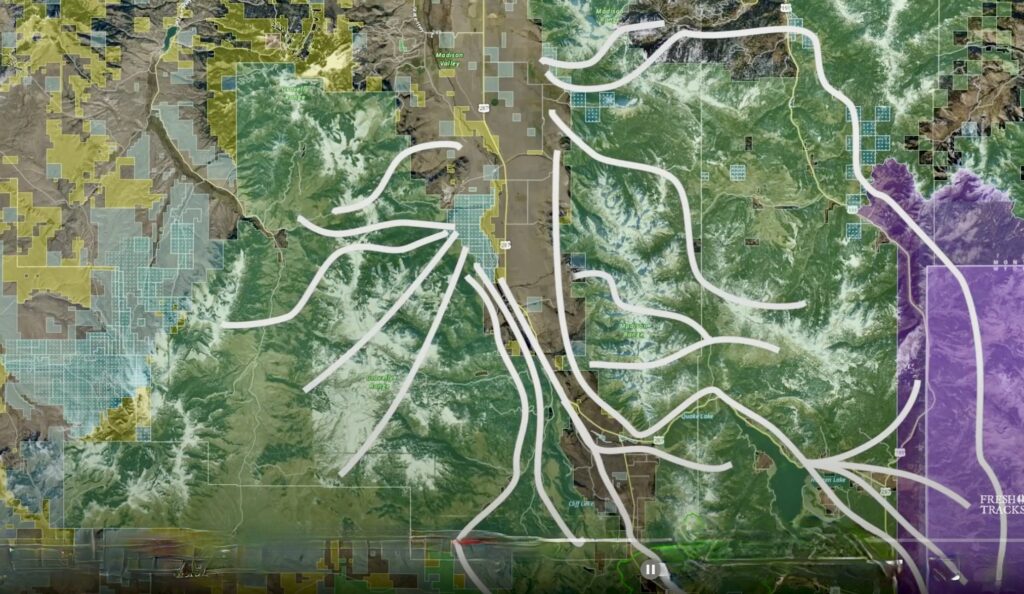

For all of the noble conservation efforts, each is a piece in a larger puzzle. None of the micro-areas exist in isolation from impacts occurring on the macro level. The sinuosity of landscape is all intertwined. In order for an elk to move back and forth between Yellowstone and the Centennial Valley, or a pronghorn between Harrison, Montana and the sagebrush near Henrys Lake, they face a human-erected gauntlet. How interconnected is the northern Madison Valley to the southern valley and onward to Island Park? Click on the link below and allow the one minute, 40-second primer prepared by Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks wow you. In bright living color, you can follow paths of different pronghorn that move up and down the corridor, for 100 miles. Lines of color turn to pools of color in the vicinity of Raynolds Pass and the flats around Henrys Lake, demonstrated how important, and how visited by pronghorn the area is.

As Reese, Diekmann and I continued our roadtrip a dozen years ago. we reached a spot along the sloping Madison foothills near Raynolds Pass that had significance to the Reese family. Together with his wife, MaryLee, the Reeses deeded a private parcel they owned there to the Forest Service so that it would be protected in perpetuity. Once upon a time, they considered building a retirement cabin there, but the couple, known for being conservation leaders, declined. Rick liked to parrot a mantra: “If you love the wild West, live in town.” He knew that was unappealing to outsiders, so he revised his slogan to: “If you love the wild West and insist on living out of town, be smart and minimize your damage.”

Not far away were a couple of other land protection deals in and around Three Dollar Bridge that Diekmann has brokered for his employer, Trust for Public Land. As we reached the road junction, where one stretch of road continues east along Quake Lake toward West Yellowstone, and another veers southward over Raynolds Pass to Henry’s Lake and Island Park in Idaho, Reese intoned:

“You need to, as a journalist, pay close attention to what’s happening in the southern Madison Valley,” he said. “You have issues of sprawl spreading in the north part of the valley between the Madisons and Tobacco Roots, between Ennis Lake and southward to [the town of] Ennis. That’s going to affect wildlife connectivity. But I really see Raynolds Pass as an emerging trouble spot.”

Reese, who passed away in 2022, never saw how prescient he was.

Parts of Raynolds Pass, near the banks of the Madison River, today resemble the non-quintessential example of wise planning. Anglers who swarm the stream in search of wild trout, and are putting up their “dream vacation homes” there are often obvious to the cost of their decision.

A stretch of U.S. Highway 87 continues southward and transcends the state boundary between southwest Montana and eastern Idaho at Henrys Lake. Eventually, that federal road connects to busy Idaho State Highway 15 that runs straight southward through Island Park, a warren of sprawl tucked into the forest just west of Yellowstone Park.

Northern Island Park is an incredibly important mixing zone for wildlife, identified by the Idaho chapter of the Nature Conservancy as one of the most important hotspots for biodiversity in the region. In autumn 2023, I wrote a profile for The Land Report of how habitat surrounding the shores of Henrys Lake—a gateway to the Centennial Valley— are threatened by commercial development and residential subdivision. In that particular case, I highlighted a success story led by Beartooth Capital of Bozeman and two citizen heroes, Rebecca Patton and Tom Goodrich, who make strategic investments to acquire vulnerable land, holding it before it can be safely conserved.

Shortly thereafter, at a location only a few miles away on land formerly used as livestock pasture, developers proposed constructing a three-story Marriott Hotel on one side of Highway 15 and an airpark on the other, located near The Nature Conservancy’s Flat Ranch Preserve. (See the image shot by Chris Boyer and location map, below, provided by the Henrys Fork Wildlife Alliance). Characterizing the tension between developer and conservation advocates was David Pace, a reporter for East Idaho News. He quoted Kirk Barker, CEO of Ensign Hospitality seeking to build the hotel. In a statement, Barker invoked the Fifth Amend of the Constitution claiming that individual property rights should trump all other matters. “This is private property, and although many have taken personal ownership of the area as open space, it remains private property.”

Speaking on behalf of the high wildlife values, Shaun Ward of the Henry’s Fork Wildlife Alliance, said, “There’s a lot of species that are in need of wild(land) – big game like elk, deer, pronghorn especially, birds like long-billed curlews or sandhill cranes that live on the flats out there. We’re very concerned with the loss of habitat that what would happen if these developments were approved.”

The battle is ongoing. Most people in Greater Yellowstone, or even Bozeman for that matter, aren’t aware of the fact that the southern Madison Valley/Raynolds Pass/Henrys Lake Flats area is home to one of the largest migratory elk populations in the ecosystem, accommodating upwards of 8,000 wapiti. In 2018, residents of Fremont County, Idaho voted on a non-binding resolution and 80 percent voted against erected three wildlife bridges over US Highway 20 at Targhee Pass. Much of the opposition stemmed from residents not wanting to have miles of what they considered unsightly fences erected along the highway to channel elk and other wildlife to the spots where the bridges are located. The irony is they didn’t want to have their views blighted by the vantage of their subdivisions found in the middle of the corridor.

Fremont County, in particular residents of Island Park, have in the past been notoriously opposed to zoning. To draw a parallel, a similar number of elk used to migrate seasonally in and out of Jackson Hole but sprawl in the early 1900s thwarted the mass movement, giving rise to creation of the National Elk Refuge which has operated as a massive winter wildlife feedlot for the last century. Remnant migrations of pronghorn and mule deer remain, connecting summer habitat in Grand Teton National Park and the Upper Green River Valley in winter. Those routes, however, are incredibly at risk to disruption.

° ° ° °

Local people love to rail against the feds, and ascribe conspiracy theories and overreach, but when it comes to prioritizing protection of wildlife corridors, it isn’t counties who have taken the lead. In autumn 2024, Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks issued an action plan for implementing the US Department of the Interior’s Secretarial Order 3362, whose stated intent is “improving habitat quality in Western big-game winter range and migration corridors.” It was actually a product of the first Trump Administration and its two Interior Secretaries David Bernhardt though mostly his predecessor Ryan Zinke, today a recently re-elected Montana Congressman. The order counts Montana, Wyoming and Idaho among 11 priority states but Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies represent the crown jewel region and it notes that corridor protection benefits hundreds of other species—as well as the quality of life residents covet.

Working together, the US departments of Interior and Agriculture, which oversee the lion’s share of public land in the West, are making matching grants and services available to incentivize private land conservation, in addition to federal funding through the US Department of Transportation for wildlife overpasses and underpasses across highways.

At the Greater Yellowstonian Biennial Science Conference, held ironically at Big Sky Resort in September 2024, wildlife migration expert Arthur Middleton touted the investment being made but recently, as he noted in his New York Times op-ed, it’s not enough. He took aim at the ultra-wealthy who have converged upon Greater Yellowstone yet are stingy when it comes to rallying for the last great concentration of wildlife in the Lower 48. “The region’s newer, high-net-worth landowners can honor this iconic American landscape by aiding local initiatives and committing to new protections on their own lands,” Middleton wrote.

Regarding the new federal effort to protect migrations, Madison Valley falls within a state priority area identified as “Southwest Montana—Bitterroot to Yellowstone” and includes the Madison, Gallatin and Paradise valleys. Because of growth issues, the possibility of safeguarding corridors in the Gallatin Valley is rapidly winnowing because of uncontrolled sprawl. This in spite of county officials having subdivision guidelines crafted by Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks available to them for how to steer development in a way that’s friendlier to wildlife. It is, however, yet another example of how land developers, when given the choice to voluntarily embrace conservation measures that could have huge positive implications for wildlife, have most often ignored them in order to maximize their own profits.

In the Madison Valley, as part of the state’s plan for implementing the secretarial order, Raynolds Pass is identified as an area of concern. Stressed is the need for land protection, conservation easements, fence removals or modifications, and weed control. Radio-collared pronghorn in the southern Madison Valley, whose movements have been tracked, represent a population of antelope that migrate the longest of any studied in the state but they and other species in the Madison navigated narrower pathways between winter and summer range that could be further constricted or severed by subdivisions.

Montana’s plan begins with a sobering message: “Many wildlife populations migrate long distances each year to survive and reproduce. These movements have become increasingly difficult due to habitat fragmentation and barriers created by a range of factors. Additionally, crucial winter range has been eroded by fragmentation, encroachments, and noxious weed infestations.” The biggest cause of fragmentation is sprawl, especially exurban development like that occurring west and north of Ennis, Raynolds Pass and the Madison County portion of Big Sky. Down in Wyoming, the state’s Fish and Game Department earlier this year noted that residential subdivision is a major threat to migrating mule deer and pronghorn moving between the Red Desert and Jackson Hole.

In the Madison, Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks oversees several state wildlife management units that are viewed as critical footholds for migration corridor protection, but animals navigate a perilous labyrinth. Not long ago, Liz Fairbank, a senior analyst with the Center for Large Landscape Conservation in Bozeman, noted that wildlife bridges are not panaceas in landscapes filled with scattershot sprawl “and no overpass has been built across a massive subdivision.” The report by Fish Wildlife and Parks noted that the Madison pronghorn migration which extends from southwest Montana into eastern Idaho, covers more than 100 miles one way.

Does actor-producer-writer Taylor Sheridan care that the attention he’s bringing to the real Madison, delivered in the name of cheap entertainment and personal profit, might contribute to its ruination?

Last summer, Dr Christopher Servheen and I were invited by a citizens’ group, Preserve Raynolds Pass, to give a presentation before a group of permanent and seasonal residents of the Madison Valley. Servheen, who had been the federal grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service for 35 years before retiring, spoke about the conservation legacy of the Madison and how sprawl could permanently erase some of its valiant achievements. I presented facts I’d gathered as a journalist writing about sprawl for decades. Many in the audience had no idea of the Madison’s global status, nor did they realize it’s a harbinger.

What’s going to happen in the Madison? With 50 percent under easement, you can choose to call it a glass half full or empty. What happens on the remaining private lands, a huge percentage holding invisible lot lines that only become reality when developed, will determine if this extraordinary dell retains its masterpiece character, or is slowly de-wilded and never capable of being re-wilded. When part of an elk or pronghorn or mule deer herd disappears from a place it has inhabited for millennia, who is there to mark and grieve its loss? Maybe not the clientele or developers of Big Sky, but real Montanans remember and they reject the rhetoric of “progress” being peddled to them.

When part of an elk or pronghorn or mule deer herd disappears from a place it has inhabited for millennia, who is there to mark and grieve its loss? Maybe not the clientele or developers of Big Sky, but real Montanans remember and they reject the rhetoric of “progress” being peddled to them.

The good news? Just because a property has been subdivided, with lot lines recorded down at a local county courthouse does not mean they must be developed. Lot lines are human creations, after all, not indelible, which means they can be undone, redrawn and configured in ways that have ecological considerations in mind, that keep subdivisions from destroying wildlife corridors. Thus, if the Madison loses its essence, it will not be because it happened by accident or inevitability, but because property owners and elected county officials chose, by choice, to avoid options that existed to save them.

In many valleys of Greater Yellowstone, citizens don’t know what to do. Preserve Raynolds Pass mobilized in 2023, in response to a proposed RV Park in the southern Madison Valley. At the forefront of resistance was a threesome of formidable women. By formidable, I don’t mean outspoken or brash, but amiable and tenacious. Their determination to scrutinize the development and marshal scrutiny proved successful. In fact, it became a kind of new community building exercise. Just as they are in Island Park and Fremont County, permanent and seasonal residents are now talking with county commissioners and enlisting planning experts to discuss how the essence of this incredible part of Madison County can be safeguarded while there is still time.

The three advocates, Kaye Counts, Marina Smith and Samantha Arbogast recently came together for an interview. They are emblems of how local citizens who care can make a difference. Read our conversation with them by clicking here.

TO READERS: Thank you for reading this latest installment of our ongoing series and investigative reports on the impacts of private land sprawl on wildlife, community and public lands. We appreciate your support.

Some other stories in the series:

The Spillover Effects Of Big Sky’s Ravenous Appetite For More

On The Front Doorstep To Yellowstone, A Montana County Wrestles With How To Confront Change

New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife

What’s Facing The Madison Valley? A Longtime Conservation Land Broker Weighs In

Refusing To Surrender Wild Ground

Proposed Suce Creek Luxury Resort In Park County Is Just “Tip Of The Iceberg”