by Todd Wilkinson

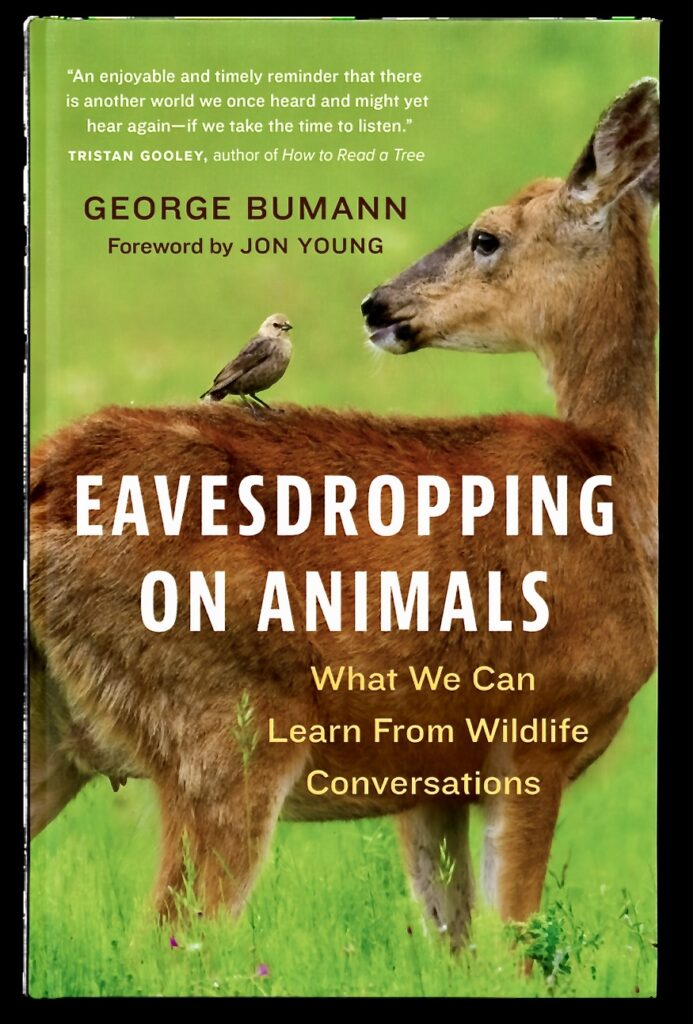

George Bumann’s fascinating new book Eavesdropping on Animals: What We Can Learn From Wildlife Conversations is not a how-to guide for translating what wildlife in his home region, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem or beyond, are telling us, or literally saying to each other.

It is instead a kind of valuable self-help book for opening the mind to a alternative way of seeing and thinking about we approach excursions the further we stride away from asphalt and the noise-filled din of human-dominated environments. It also helps those who are drawn to nature better figure out how they can be more present, and live more meaningfully in moments, by undistracting ourselves from the constant barrage of electronic overstimulation. Focusing on the ancient soundscape of the natural world can be liberating. For those who do it, as Bumann has witnessed firsthand in America’s first national park, such experiences are transformative and life-altering.

Together with his wife, Jenny Golding, and their high-school-aged son, Bumann lives just beyond the northern boundary of Yellowstone on a hill above Gardiner, Montana. Jenny is a talented photographer. Bumann is a wildlife sculptor and an admitted nerd when it comes to, metaphorically speaking, exploring rabbit holes of curiosity whenever he’s trekking outdoors. George and Jenny also founded the annual Yellowstone Summit that allows people who love Greater Yellowstone, no matter where they live in the world, to beam in remotely from locations around the world and hear presentations made by scientists, artists, landowners, nature-tourism and others. Yellowstonian is proud to be a partner with the Yellowstone Summit. Bumann’s sculpture can be viewed by clicking here and he and Jenny created a blog called A Yellowstone Life.

Here, however, the focus is on a book that’s been in the works for years and among Bumann’s fans is long awaited. He is having a book reading at Elk River Books in Livingston on Thursday, October 24 at 7 pm. Below is a conversation we recently had.

YELLOWSTONIAN: What was the inspiration behind your book?

GEORGE BUMANN: The inspirationwas to share with a wider audience what my students here in Yellowstone, and through online courses on animal language, have been able to experience. This is the book I also wish I had growing up as a boy when I felt outside of the lives of my wild neighbors and strives to save readers the decades of time it took me to figure out so many things.

YELLOWSTONIAN: How did, if any, the writings of naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton who wrote Wild Animals I Have Known in 1898 figure into you wanting to bring a New Millennium way of thinking to how we approach the great out of doors? Seton was criticized for bringing sympathetic portrayals to animals that had been demonized and it was that demonization that aroused social animosity, used as a lever by politicians to enact policies that justified the eradication of certain species. Now, looking back, it seems that science has justified Seton’s ability to see sentient qualities in non-humans, which your book powerfully delivers.

BUMANN: Seton definitely inspired me when I was young, both as a naturalist and as an artist. His writing and his ink drawings pulled me in, and made me want to look closer to the world around me. His lesser known book on animal anatomy for artists, in particular, still contains several gems that I have not found anywhere else.

YELLOWSTONIAN: In so many areas of our lives as humans, we expect other beings to understand our verbal and body language, and indeed many species are able to read us. Think dogs, cat, horses, livestock and even birds. Why is it important for us to become listeners of them in their vocalizations, body language and behavior? What can we learn from animals?

BUMANN: Listening broadens the field of experiences we can have. Closer observation through all of our sense lets us go beyond chance encounters with wild animals and into intentional, inspiring, and transformative connections with the more-than-human community. Animal super powers can elevate our own awareness several fold, from the turned-over garbage can a block away to knowing about a hidden wolf traveling behind a distant ridge. Animals can hear things we cannot (such as infrasound or ultrasound, I.e. low and high frequencies), they can see things we will never see (think ultraviolet light) and consequently, can teach us about so much that we would otherwise miss. There’s far more to life than meets our own eyes and ears and as we learn to listen to these others, we see things a bit more from their perspective and then, in turn, come to have a better appreciation of them.

“Animal super powers can elevate our own awareness several fold, from the turned-over garbage can a block away to knowing about a hidden wolf traveling behind a distant ridge. There’s far more to life than meets our own eyes and ears and as we learn to listen to these others, we see things a bit more from their perspective and then, in turn, come to have a better appreciation of them.“

—George Bumann

YELLOWSTONIAN: Everywhere we turn, we hear more about how important the therapeutic effects of exposure to nature are, in terms of being mindful and present, shedding stress and gaining grounding in an often chaotic modern world. Your book does not recommend that readers engage in high-adrenalin activities that cause the brain to produce and then crave rushes of dopamine. It is an argument that asserts just the opposite. Can you elaborate on that?

BUMANN: When I’ve hit my limit with office work or the stress from any number of things, Jenny (my wife) will often say, “You need to get outside and go for a walk,” and she’s right. So many times others see the accumulated strain of modern life building in us before we see it ourselves. Nature feeds us in all of the best ways—and many an extreme adventurer has found greater joy through sensitizing themselves to the wild creatures they typically power hike past, and as a result, enjoy a more meaningful existence. Vitamin N, as the author Richard Louv puts it, is essential. Starting on a diet of silence and Nature’s influences is good for all of us and not only makes us better listeners to the wild world, but also to your friends, family, coworkers, and ourselves. AND it’s FREE! Let our culture/economy feed its attention deficit disorders elsewhere; you will be happier, healthier because of it.

YELLOWSTONIAN: What are the species that really speak to your own inner being, and why? How did you come to realize the depth of connection?

BUMANN: I find it hard to isolate one species as being particularly inspirational. When you meet a member of another species on its own terms, any of them, and more accurately any individual can be deeply transformative. I have had tremendous encounters with the larvae of predacious diving beetles sipping small breaths of air from their stagnant, watery homes, grieved along side a mule deer who has lost all three of her precious fawns, and I have been drawn to emulate the perseverance of an injured wolf that still strives to keep up with its pack. I like to think that all species show can show us a better side of ourselves. They help us reflect. “Could I keep going under those conditions? If they can, maybe I can carry my burden.” And we become better humans because of it.

YELLOWSTONIAN: One of your close friends is conservationist Jeff Reed, who lives down the road in Paradise Valley. He’s a native Montanan who, rather eccentrically, blends a dual interest with linguistics and being a software engineer. Those talents have come together with the bioacoustics work he is doing with scientists in Yellowstone and elsewhere. Among the species are wolves and elk. How has your friendship with Jeff affected the way you think about “eavesdropping?’

BUMANN: My relationship with Jeff gives me hope that we can reclaim so much of what we have lost. Not so long ago, each and every one of us was exquisitely attuned to the minute, details of the natural world. Those natural wonders were at the center of our very survival and so much community banter. That banter was also underpinned by thousands of generations of others doing exactly the same thing, over and over, and handing those riches to you at story time. Technology, Jeff’s unique background in linguistics, and so many new scientists and thought leaders, are reminding us of what is possible when we slow down and listen in this modern age. The speed at which technology allows us to learn these days—think internet search engines to find product reviews and DIY tutorials, and the Merlin Bird ID app to identify backyard birds by sound—makes us better suited to take our seat at the great campfire again without having to wait a few thousand generations to experience the benefits and the beauty of it all.

YELLOWSTONIAN: You hail from a family of origin comprised of artists. And you’ve gained critical standing as a wildlife sculptor interpreting your subjects three dimensionally. Your wife, Jenny, is a talented photographer. How does your creative ways of interpretation cross over into the ideas you’re conveying in the book?

BUMANN: Each of us have our inner talents and by knowing people of varying abilities, it helps us see the reality of our lives through a different lens. Sculpting lets me see deeper into things I might normally pass by such as the structure of an elk’s ribs or pelvis as it turns in the sunlight. For Jenny, she would probably say the same of photography or songwriting. Regular exposure to nature helps put a spotlight on those talents we all have. The reflections of ourselves as found in nature, help also us to identify those things we excel at and where we are best able to contribute, whether it is interpreting the meaning behind a dip in a bird’s flight or finding solutions to community challenges.

YELLOWSTONIAN: The way you live your life is an attempt to be conscientious and always curious. For parents and grandparents who may be interested in your book, what tips can you offer, as a father yourself, for how to raise a child who carries forward the imprint of nature with them?

BUMANN: Be someone’s hero—my maternal grandfather was that for me. As a father, aunt, uncle, or grandparent, model curiosity. Which specific blooms does a butterfly nectar on? Embrace awe at the intricacy of an ant colony. Clear the calendar—if only for an afternoon—and put the watches away, wander. Make room for serendipitous discoveries and follow wherever the breadcrumbs lead. Stoke the fires of wonder in the young people in your lives. Older mentors give permission and power to children to follow their innate tendencies and discover their superpowers. Send them on ‘missions of discovery’. Where do those frogs you hear each night hide during the day? And capture their stories when they return to share in their adventures. With time, the strength and direction of their own inner compass will take shape under the influence of nature, and it will serve them for a lifetime.

“Eavesdropping on wild conversations, as it turns out, offers a direct source of intel that comes straight from our wild, nonhuman cohabitants in your exact location. And this applies whether your home is in an urban, suburban or rural environment. Look for the diversity of life, it is one of the greatest bellwethers to the status of things close at hand. On the larger scale, Mother Nature should have a seat at every corporate board room table.“

—George Bumann

YELLOWSTONIAN: You and Jenny set up a website called A Yellowstone Life and you two are the force behind the annual online Yellowstone Summit which brings thought leaders related to Greater Yellowstone together and I’m happy to say that Yellowstonian is a collaborator. All of this emanates from the fact that you decided to settle on the edge of Yellowstone near Gardiner. How did you make that decision and how has it shaped the direction of your life?

BUMANN: It was Jenny who first brought me to Yellowstone. After finishing graduate studies I was happy to leave academia and follow her wherever her heart led—my only criteria was that whatever place we went had to have some “weeds and water for me to wander around in.” Jenny had worked here in the 1990s on a coyote research program at the time of wolf introduction, and that patch of weeds and water turned out to be Yellowstone. We celebrated our first anniversary driving through the east entrance to the Park to take seasonal jobs, with all of our worldly possessions packed in the back of our truck and a small U-Haul trailer, including the stale wedding cake top that we had carried across the country in a white, plastic cooler (it tasted awful!). We moved into the Lamar Valley Buffalo Ranch—and ultimately, to the community of Gardiner, Montana—to live and work for the then Yellowstone Association (now Yellowstone Forever). The move here has been nothing short of transformational. So many opportunities opened up to us that had not existed before by settling down here. But, to be honest, the first time I ever saw Gardiner, which was during the month of July, I wondered at who would live in this “Browntown,” that seemed scorched by the mid-summer sun? Now, I can’t imagine living anywhere else. The bonds with the land and the people have created strong bonds of connection that have added immeasurably to this place we call home.

YELLOWSTONIAN: What’s the most important thing we can do to protect and preserve the wild places closest to us?

BUMANN: To preserve wild places, we must first become aware of how each choice we make affects their vitality. A fence just isn’t a fence—it can make or break millennia-old animal movements. A second home is not just an additional structure in a unique place—it could be an unrealized ‘keep out’ sign to animals who demure at the slightest hint of man. Secondly, consider how many life services wild lands provide to us free of charge (in actuality, its worth trillions of dollars worldwide); think clean water, clean air, and a less stressful lifestyle. Does your choice to mow that part of the lawn, build an access road, leave the exterior lights on all night, or clearing some unsightly brush, add to or detract from nature’s ability to provide those services? If you are uncertain, ask around, do your homework. Eavesdropping on wild conversations, as it turns out, offers a direct source of intel that comes straight from our wild, nonhuman cohabitants in your exact location. And this applies whether your home is in an urban, suburban or rural environment. Look for the diversity of life, it is one of the greatest bellwethers to the status of things close at hand. On the larger scale, Mother Nature should have a seat at every corporate board room table, for has been said, Mother Nature always bats last.