What kind of art moves you to reconsider your point of view, take action or perhaps even embrace the ambient outdoors—and the survival of those wild residents—in a new, more meaningful way?

Jane Goodall once said, “You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference and you have to decide what kind of a difference you want to make.” Related to this, French Modernist painter Marc Chagall once remarked that “great art picks up where nature ends.”

Of course, there is not a beginning or end to nature on our planet, nor do we live apart from it because we, too, are creatures of its invention. The question facing us is how do we not foul the life-giving maw in which we are totally immersed?

The National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole—the only museum in America that won Congressional/presidential approval to be “the official wildlife art museum of the US”—is among the must-see human landmarks in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Located on a bluff north of the town of Jackson, it offers commanding views of the National Elk Refuge off to the east and an impeccable glimpse of Sleeping Indian (Sheep Mountain) that rests on a crest of the Gros Ventre Range. Along the museum’s outdoor “sculpture walk” and inside its quiet, soothing gallery spaces are historic and contemporary portrayals of wildlife in paintings and sculpture considered masterworks.

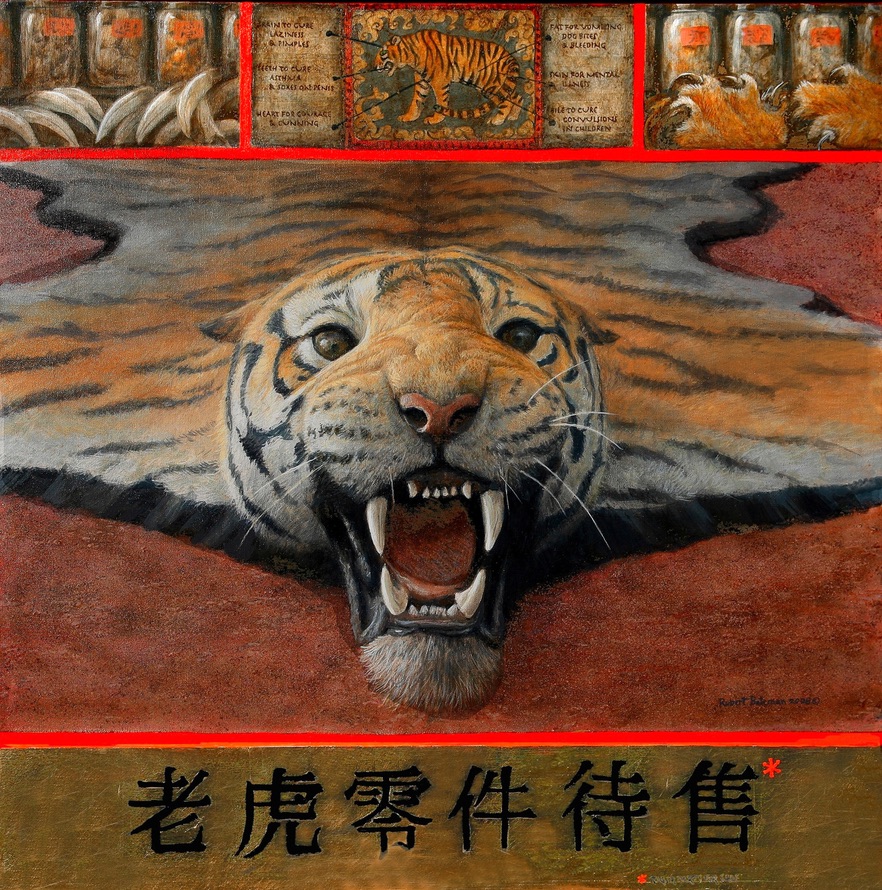

Wildlife art continues to evolve as a response to our own time and a new exhibition titled Environmental Impact invites us to reflect on the rise of modern conservation consciousness. From holding a mirror up to us in the time of the Anthropocene (or human-dominated epoch), it is evocative, engaging and educational. Seeing it provides a perfect escape for road-wary summer travelers or locals needing a peaceful break from dealing with crowds at the height of tourist season. Be forewarned: this is not a collecting of pretty pictures.

David Wagner put together the traveling exhibition and it is on display at the museum through August 25, 2024. Environmental Impact features paintings, sculptures, photographs and other pieces. Those who think of wildlife and nature art as reflecting only the past will gain a new perspective in seeing how contemporary art can be a prompt for reflecting on how we live in the modern world. Recently, I had a conversation with Wagner.

Todd Wilkinson: What are some of the elements that set Environmental Impact apart as a curated traveling exhibition and why do you think the National Museum of Wildlife Art is a perfect venue?

DAVID WAGNER: Environmental Impact is comprised of art that makes an overt statement on a range of environmental subjects that will be of interest to any astute reader of Yellowstonian. The exhibit is not actually a pure wildlife art exhibit like you find with the Society of Animal Artists annual traveling Art and the Animal show. Many deceased and living artists in the National Museum of Wildlife Art were members of the Society of Animal Artists.

This exhibition is different. Most wildlife painters create pretty pictures and wildlife sculptors generally sculpt subjects representationally in 3-D. Case in point: Consider another annual exhibition sponsored by an organization named Artists for Conservation. While the artists in that group ally themselves in name to the cause of conservation, the art in their exhibitions is devoted more to the aesthetic of subjects and is not generally overt when it comes to making a pictorial statement about the context in which those species survive.

The National Museum of Wildlife Art is the perfect venue for Environmental Impact for a couple reasons. First, Its attendance is out-the-roof in summer when the exhibition will be there, offering the artists and their causes wide exposure. It is the premiere wildlife art museum in the world. Second, while the museum’s own permanent collection and past exhibits are top notch in terms of quality, they’ve tended to be paradigmatic, i.e. beautiful imagery but unchallenging ideologically. Don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing “political” about the art in this exhibition but it does challenge viewers to think and I commend the National Museum of Wildlife Art for fostering it. Environmental Impact allows the museum to spread its wings and extend its relevance to topics of the day framed within the environmental challenges we are facing, from loss of habitat to using the oceans as a dumping place for our unwanted waste. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is a place where so many topics involving the intersection of nature and humanity are top of mind for millions of people headed to Yellowstone and Grand Teton. Some of these pieces are provocative and could easily appear at the Museum of Modern Art.

TW: You’ve long been saying that art ought not just have a rear-view, romanticized perspective of nature but reflect contemporary concerns and values. How has that been validated with the success of Environmental Impact?

WAGNER: Sculptor Kent Ullberg, whose work is in the museum’s permanent collection apart from this show, is fond of saying that his sculpture, though not considered “modern” by some because it is representational as opposed to being abstract, is contemporary. He argues there is no greater contemporary issue confronting the planet today than the loss and degradation of the environment and the wildlife inhabiting it. Kent’s work is in Environmental Impact along with the works of 35 other artists. This includes other big-name artists like Robert Bateman who, among others, have courageously expressed their passion for environmental causes through their artwork. Regarding validation, consider the fact that 25 museums nationwide hosted Environmental Impact I from 2013 to 2016 and its sequel Environmental Impact II from 2019 to 2024, which is now in Jackson. Those museums have drawn thousands upon thousands of visitors including students who will inherit the future, to see the exhibit and be moved by it; not to mention the fact that these museums have also promoted the exhibit and the artists’ causes through media coverage, paid advertising, and social media.

TW: What are a few of the pieces in the exhibition that speak to the strengths of engaging viewers and the messages they send?

WAGNER: In fairness, I’d have to say, they all do. But let me start at the beginning—in the late ’80’s, with the seminal work of Canadian painter Bateman, Swedish-born sculptor Ullberg, American artist and poet Leo Osborne, and Israeli painter Walter Ferguson, who together, artistically contributed to the environmental movement and its connection to fine art. Bateman lives in British Columbia, Ullberg in Corpus Christi, Texas and he had a studio in Loveland, Colorado, and Osborne has been based in the Pacific Northwest.

The exhibition features iconic works such as Requiem for Prince William Sound, Ullberg’s elegy to wildlife victims of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska, the worst man-made ecological disaster of its time; and

Still Not Listening, a poem and sculpture of the same title by Osborne which expressed frustration and outrage of environmentalists worldwide. While the Exxon Valdez spill was a single event, it was symptomatic of larger issues and challenges confronting the planet’s plants, animals, and habitat, which still continue.

To address threats to marine life and old-growth forests posed by commercial fishing and logging conducted globally on an unprecedented scale, painter Bateman dedicated an entire series to environmentalism beginning in 1989 with Mossy Branches —Spotted Owl, a potent symbol in the Pacific Northwest where the cornerstone of economic life—logging—was not only effected by but actually impinged upon the bird’s status under the Endangered Species Act. Taking advantage of the opportunity that his success afforded him, Bateman pushed the limits of environmental art even further by creating a controversial painting that contrasted old-growth and clear-cut forest imagery in a new style altogether.

The first in what Bateman called his “environmental series,” Carmanah Contrasts, grew out of a collective effort by artists who gathered on Vancouver Island in British Columbia in 1989 to document the clear cutting of Carmanah Forest, an old-growth area where ancient trees still grow. They agreed to collectively publish their work and create awareness and resistance. Bateman continued his “environmental” foray with other brave and powerful paintings, notably, in 1993, with Self-portrait with Big Machine and Ancient Sitka, and Driftnet (Pacific White-sided Dolphin & Lysan Albatross), a painting that exposes the grim realities of commercial fishing and bycatch.

For maximum impact, Bateman overlaid the painting with actual non-biodegradable commercial fishing netting, net that could cut, entangle and kill unintended victims with ease. The work of American-born, Israeli painter, Walter Ferguson was on the same trajectory in the late ’80s but his imagery represents a more Global perspective. The work of these four artists was seminal. And therefore, serves as the starting point historically speaking, for thinking about Environmental Impact.

TW: So, in some ways, it is a commentary about the hard truths of co-existence.

WAGNER: Every week we read about concerns over clearing of the Amazon rainforest to grow crops and how it causing a collapse of biodiversity. There are some pieces in this exhibition that speak to climate change, pollution and other issues. It’s not preachy and will make you feel more wide awake than when you entered.

TW: There is an intriguing dichotomy between the museum’s permanent collection and the works in this show. It’s important for readers to know that one of the most popular pieces in the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s permanent collection is a large portrait of a bull bison by Bateman titled Chief. In addition there are many works by Carl Rungius, considered the greatest painter of North American “big game” animals, who spent time in Wyoming and Banff, Canada. He won recognition by the National Academy of Design for a portrayal of a Wyoming cowboy near the Wind River Mountains. Rungius, who could have otherwise been an acclaimed human portrait painter or landscape artist, chose wildlife because those subjects spoke to his heart. While Rungius isn’t in your exhibition, the National Museum of Wildlife Art has the largest collection of Rungiuses on public display in the US.

WAGNER: What makes for a wonderful contrast in thinking about how artists from different eras presented nature. Many of those Rungiuses could be in any fine art museum in the world.

“If you want to truly experience art, then you must do so in person and it’s part of a tradition your ancestors enjoyed. Anything else is a faded experience. The art in the National Museum of Wildlife Art is an echo of the amazing natural landscapes in Greater Yellowstone.”

David J. Wagner, guest curator of Environmental Impact

TW: You wrote a book called American Wildlife Art that examines the evolution of wildlife art from being largely works that chronicled the decline of wildlife in America and charted its rise through conservation-minded hunters. Again, it’s much more today. Is the appeal of wildlife art more of an American phenomenon or is it worldwide? Are there differences between how different regions of the world venerate wildlife imagery?

WAGNER: I would say North Americans are more familiar with wildlife art and certainly the array of species you see represented because those animals are, fortunately, still on the landscape. They are not artifacts that appear in art. In Europe, so many of the large mammals have disappeared or exist at low numbers due to human population pressures. In general, however, animals have been the subject of art of all kinds throughout all areas of the world. They appear in cave paintings in France and Spain and as petroglyphs and pictographs in the Americas. The breadth and depth of animal-related artistic idioms throughout the course of human time is enormous.

TW: You also curated an exhibition of works by Jackson Hole photographer Thomas Mangelsen that appeared at the National Museum of Wildlife Art a few years ago. That exhibition has traveled widely. How successful has it been and why?

WAGNER: Nearly 30 museums have and are still scheduled to host Thomas D. Mangelsen—A Life in the Wild. The tour has taken Tom’s photographs nationwide and in Canada since 2019. Because of demand by museums, the tour morphed into a dual tour, with two exhibits traveling the nation simultaneously. In terms of traveling museum exhibitions, that’s about as successful as it gets. The exhibit’s success is due to quality, the appeal of its subject matter, technical accomplishment before and after digital, and familiarity about Tom’s photographs among the general public.

Mangelsen is not only a great photographer, but he’s become one of the best known living nature photographers out there and known particularly in recent years for his images celebrating Jackson Hole Grizzly 399 and other bears and animals in the valley. Plus, he was profiled on 60 Minutes and that kind of exposure has brought widespread familiarity. These are among the reasons for the exhibit’s success, another of which is that wildlife photographers from around the world come to Jackson Hole and the Greater Yellowstone region because of the abundance of animals still wild and free.

TW: What can wandering through a museum do for the human spirit and soul that other experiences cannot do? And if you encounter young people who might be reticent about visiting a museum, what would you say to them if they tell you: “Museums are boring. They aren’t exciting.”

WAGNER: Museums offer object-based experiences.They encourage the viewer to slow down and sit still instead of being encouraged to always move fast physically and mentally through spaces.That’s also fundamentally different than a digital vicarious experience on a screen. Objects time-travel. They are physically real, and generally one of a kind. They have been in the hands of their makers and many have had a fascinating journey going from artist’s studio to reaching the museum. Objects are truly authentic and there’s probably, in the case of paintings, literally some of the artist’s DNA attached. Knowledge about the works offer real clues and can reveal a deeper awareness about our textured, organic, living world.

TW: You are not a big fan of virtual reality?

WAGNER: Not as an easy replacement for the real priceless thing. Artworks viewed on-line are comprised of pixels and are not authentic. If you want to truly experience art, then you must do so in person and it’s part of a tradition your ancestors enjoyed. Anything else is a faded experience. The art in the National Museum of Wildlife Art is an echo of the amazing natural landscapes in Greater Yellowstone. Regarding kids, here’s an anecdote: My family and I were once visiting Vienna, Austria. To make the experience memorable for my young son, I used my connections to arrange a kind of scavenger hunt led by one of the museum’s educators to find little gems throughout the museum’s vast collections of masterpieces. It was great fun for everyone. Years earlier, I had done some of the coursework for my Ph.D. in Vienna, and studied at The Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien myself. Call me biased, but I’d say a visit there or any great museum is as exciting as anything imaginable.

TW: You’ve visited many of the great museums of the world. Why do you hold the National Museum of Wildlife Art in such high esteem?

WAGNER: Because its collections embody the vision that its founders, the late Bill and Joffa Kerr and their closeknit group of family and friends, intended for it. As proud as I am to have my traveling exhibition, Environmental Impact, on display at The National Museum of Wildlife Art, what truly makes it great is not the traveling exhibitions it hosts.The greatness comes from the quality, breadth and depth of its permanent collections, the core of which was made available by the Kerrs. The collection has grown and gained even more prestige thanks to its patrons, board members and dedicated staff still carrying on its legacy. At the same time, more global attention has been brought to Greater Yellowstone. Incidentally, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the Kerr’s family foundation—The Kerr Foundation—funded the research and writing for my book, American Wildlife Art.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF WILDLIFE ART: From May 1 – October 31, the museum’s galleries are open daily from 10 am to 5 pm. During this summer season, its eatery, the Palate Restaurant, which is a great place to have lunch or grab a coffee, is open from 11 am to 2:30 pm. For those interested in having a picnic there is always the sculpture walk lined with monumental bronzes by some of the best wildlife sculptors in recent years. Admission to the museum is $18/adults; $16/seniors; $10 for the first child and $5 for any children after. Children four and under are free. Again, it’s a perfect venue for spending a quiet, restful day.