by Todd Wilkinson

The federal scientist who for 35 years led efforts to revive grizzly bear numbers in the Lower 48 says the original recovery plan he wrote three decades ago is now outdated and in urgent need of revision.

Dr. Christopher Servheen, formerly the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s national grizzly bear recovery coordinator, is sending comments to the country’s top wildlife agency saying that destructive trends affecting bear habitat, policies hostile to grizzlies enacted by western states, and geographic isolation between individual bear populations undermines ongoing biological recovery. Until they addressed, he believes grizzlies should not be delisted.

Servheen spells out his concerns in a document being submitted to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s current national director Martha Williams, and it is being circulated by the non-profit environmental law firm, Earthjustice, which has twice successfully overturned efforts made by states to remove grizzlies from federal protection.

Servheen’s concerns and suggestions are endorsed by a group of scientific colleagues who have devoted their careers to studying variables essential to maintaining viable grizzly bear populations.

The document’s submission is unprecedented in the history of the Endangered Species Act. Never before has the lead federal scientist, who played an instrumental role in rescuing a species from extirpation, reversed course in his thinking about delisting and who now says the basis for his earlier optimism is no longer justified.

During the 1990s and into the first decade of the new millennium, Servheen in his official role with the US Fish and Wildlife Service was routinely called to testify and support delisting as an expert witness. Often, his credentials were touted by lawmakers from the West seeking to have grizzlies removed from federal protection and their management handed over to the states of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho. Each of those states have signaled their intent to sanction a sport hunt of bruins.

However, in 2023 as a private citizen retired from government service and in his new capacity as voluntary co-chair of the North American Bears Experts Team for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Servheen told lawmakers on Capitol Hill that he opposes delisting. His rationale is spelled out in his assertion that grizzly bears are still at grave risk and the recovery plan needs to be amended.

Servheen provided an overview of his analysis to Yellowstonian. “The challenges grizzly bears face now are much different than in 1993 when I wrote the recovery plan,” he said. While great gains have been made in stabilizing a Yellowstone-area population that he believed was headed for potential disappearance in the early 1980s, Servheen says a number of things need to be revised in recognition of new emerging threats.

ALSO READ: New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife

In order to achieve true biological recovery, Servheen said, grizzlies in the entire Northern Rockies should be managed as a single interconnected population—known in science as a metapopulation—not as one clustered in Greater Yellowstone, another in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem encompassing Glacier Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and three or four other small remnant population. Achieving a single interconnected population, which could be years away, “would increase genetic diversity and thereby genetic resiliency, and demographic and climate change resiliency “to achieve what he considers real durable recovery and eventual result in delisting of bears.

The goal of establishing a meta population could be achieved by working with communities to reduce human-bear and livestock-bear conflicts, using tools and techniques shown to yield results. States, he noted, should commit to elimination of what he calls “anti-carnivore practices” that are unsupported by science as effective management tools.

Among the most troubling for Servheen are practices allowing the snaring and trapping of wolves bait in known grizzly range and “which will kill bears when they are out of their dens,” he said. He also condemned the practice of allowing black bears to be hunted with hounds where grizzlies are present, which, again, he said, “is certain to result in grizzly deaths.”

Servheen is concerned that states are going to implement efforts to reduce grizzly range and numbers immediately upon delisting, even when bears are not causing conflicts. The states, he said, need to commit to continuing careful management of grizzly mortalities inside and outside recovery areas within the metapopulation area after delisting. “This would need to be unlike what the states have done with wolves where they eliminated careful management upon delisting and instead implemented aggressive new killing policies, some of them unethical, to try and reduce wolf numbers to minimal levels,” he said.

The states need to commit to continuing careful management of grizzly mortalities inside and outside recovery areas within the metapopulation area after delisting. “This would need to be unlike what the states have done with wolves where they eliminated careful management upon delisting and instead implemented aggressive new killing policies, some of them unethical, to try and reduce wolf numbers to minimal levels,” Servheen said.

He pointed to Wyoming and it allowing snowmobilers to use their machines as lethal weapons to run down and kill wolves and coyotes, “which he says violates every tenet of fair chase , ethics and civilized behavior that professional wildlife managers and hunters strive to uphold.”

Although snaring, trapping, hounding, and baiting of black bears when grizzlies are out of their dens can be prohibited, and tactics adopted to reduce conflict between grizzlies and livestock, what cannot be reversed, he said, is habitat destroyed by sprawl. [Read a new report on the ecological impacts of private land sprawl on Greater Yellowstone’s world-renowned wildlife by clicking here].

Given huge emerging growth issues in the Northern Rockies, states, he said, should work closely with counties in their planning strategies to slow detrimental impacts on wildlife, such as rapid habitat loss for grizzlies and other wildlife due to rural development. He said fragmentation of private landscapes is undeniable and noted how half a dozen public opinion polls in Montana have corroborated that Montanans are concerned about the pace of sprawl, including in valleys that are crucial to establishing biological connectivity.

Nearly two decades ago, Servheen and the Fish and Wildlife Service required that all national forests in Greater Yellowstone revise their management plans and commit to strict habitat protection standards for bears before delisting could move forward. Servheen says “there ought to be a parallel commitments requiring counties in established grizzly bear habitat to management development and sprawl to limit detrimental impacts on valued wildlife like grizzlies, elk and mule deer.”

With regard to the proposed metapopulation approach to grizzly management, Servheen said it is not new. In fact, it was recommended by the Montana Governor’s Grizzly Bear Advisory Council in their 2020 report. Read page 13.

The advisory council, widely hailed, was made up of a wide range of Montana residents including ranchers and citizens representing a wide range of interests. “I hope the Fish and Wildlife Service and the states will recognize that real recovery and delisting requires use of the best available science and that is what is in the proposed recovery plan revision. “The challenges grizzlies face are much different today than what existed in 1993.”

While Servheen says his concerns are biological, not political, there is no debating that politicians who previously have advanced legislation to compel delisting have referenced numeric metrics for gauging recovery. The Endangered Species Act also requires that adequate regulatory mechanisms be in place to control mortality and habitat development on public land so that delisting does not result in eventual declines once again. These criteria were devised by Servheen himself in concert with the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, counted among the most respected wildlife research units in the world.

The main metrics are: estimated number of bears inside the primary recovery zone which hovers at around 1100 individuals in Greater Yellowstone and roughly an equal number in the Northern Continental Divide; wider distribution of bears on the landscape; estimated number of unduplicated sightings of mother bears with cubs; and thresholds of acceptable mortality. As Servheen notes, there are many times the number of bears than when they were listed in 1975 and they are dispersing. There also are a lot more mother bears with cubs.

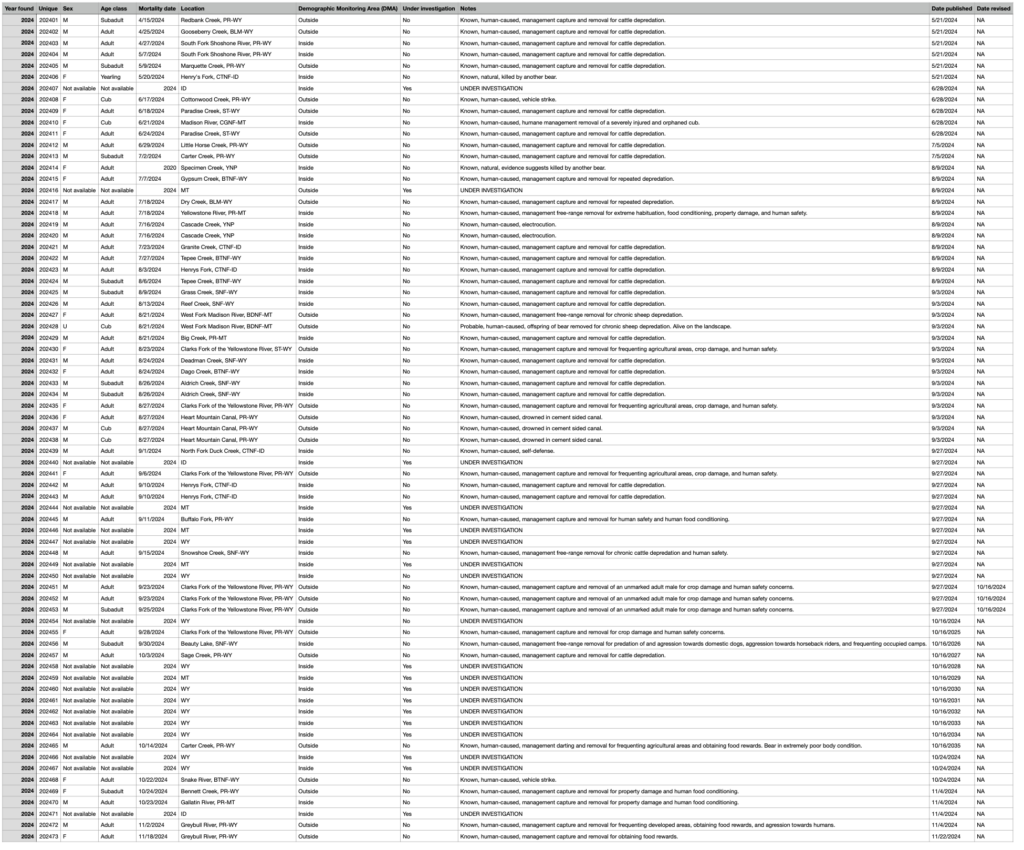

However, this year is a record for the number of bears that have died—at least 73 in 2024. Servheen notes that it’s not a number of bears estimated to be alive in a population in a given year, but whether there is ample habitat and conditions that can sustain a population over time. At present, the likely trajectory of the bear population is, at best, uncertain and state policies designed to control bear numbers without reason is concerning, he said.

Places in 1993 where Servheen believed grizzlies could safely move through the landscape, including millions of acres of private land, have become fragmented by exurban sprawl and ranches and farms converted to residential subdivisions. The loss of habitat on private land is detrimental not only to grizzlies, Servheen says. It is affecting many species. In fact, it is estimated that 80 percent of species in Greater Yellowstone rely upon private land habitat for survival.

Servheen says public lands by themselves are insufficient to sustain some populations of wildlife and that the roster of what once was considered suitable, secure habitat outside of national parks and national forests needs to be re-assessed. “Today there are hundreds of thousands of additional people living in grizzly bear range and a lot more structures than there were in 1993 when I wrote the recoveyr plan,” he said. “ If we are really going to be making decisions about species recovery based upon the best available science, as various laws require, then we need to update the recovery plan and understand and address the impacts of accelerating sprawl.”

In 2018, when a federal judge ordered that Greater Yellowstone’s population of bears be relisted, he said the arguments made by Earthjustice and other groups, that connectivity be achieved between Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide were persuasive. Isolated populations limit genetic diversity. But Servheen says the answer is not simply trap a few bears and drop them into another ecosystem to bolster the gene pool.

“Grizzly movement between ecosystems and across the landscape is dependent on reducing mortality sources to grizzlies such as conflicts with humans and livestock and enhancing ways that residents, particularly livestock producers, can operate in grizzly range with minimal conflicts,” Servheen said. “It is important to realize that only about two percent of the grizzly population has conflicts with livestock. We can reduce livestock conflicts by helping livestock producers with tools to reduce such conflicts. It is also important to not place grizzly killing mechanisms like wolf trapping and neck snaring with baits, and hound hunting of black bears into these areas while grizzlies are out of their dens. Wildlife road crossing structures are useful in some areas, but the broader, landscape level reduction in grizzly mortality is most effective way promote functional connectivity between ecosystems.”

Having a metapopulation of bears creates a more resilient population that can better withstand habitat fragmentation, disruptions to natural foods that cause bears to wander farther, and vulnerability to potential disease outbreaks. When any species becomes fractured into small island subpopulations, each one geographically isolated from one another, they are become more vulnerable to impacts that can speed their decline and eventual disappearance.

Within the last 20 years, areas that scientists believed were readily conducive to bears dispersing from Greater Yellowstone and connecting with grizzlies in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem has been fraying due to a huge surge in sprawl affecting mountain valleys, as seen in this graphic, below, prepared by Headwaters Economics.

Dr. Charles Schwartz, who previously oversaw the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team prior to its current leader, Dr. Frank van Manen, is today among those who endorsed Servheen’s document seeking a modern update of the recovery plan.

Schwartz has been an author or co-author of several peer-reviewed scientific publications examining everything from grizzly bear foods to the impact of residential development. One paper, in particular, published a dozen years ago, assessed the negative consequences of residential sprawl on grizzly behavior and habitat. In that analysis, grizzly reproduction dropped below replacement when there was as few as one home on a section of land.

Consequently, build out scenarios effectively changed source habitats without homes to sink habitats once a new house was projected to be developed. As expected, the boom growth scenario resulted in a higher percentage of source habitat being converted to sink habitat “ A “source habitat” is one that fosters growth in bear numbers. A sink is one that results in decreasing bear numbers.

The paper states, “Projected development in the Big Sky-Moonlight Basin, Montana area has the potential to fracture currently contiguous, secure grizzly bear habitat. Big Sky-Moonlight Basin are private lands located within occupied grizzly bear habitat east of Madison Valley. Development in the Big Sky area already constitutes sink habitat and projected development west of Big Sky in the Moonlight Basin could potentially fracture the Lee Metcalf Wilderness to the north from undeveloped forest service lands and the Lee Metcalf Wilderness to the south. Projected development in the Henrys Lake area of Idaho may also create a fracture zone for grizzly bears attempting to move between Forest Service lands west of the continental divide and east of the Henrys Fork with the Centennial Mountains in Montana and Idaho to the west, a possible linkage between the GYE and the Bitterroot Range. Grizzly bears currently occupy this area and are continuing to move west into the Centennial Mountains east of Interstate Highway 15.”

The paper goes on, “Projected development west of Cody, Wyoming, including the North Fork and South Fork of the Shoshone River, will make the interface between secure grizzly bear habitat and the urban interface adjacent to Cody, Wyoming, more clear. Projected development in the drainage of the river will also add to the already existing fracture zone created by roads and developments in the valley bottoms projecting into secure grizzly bear habitat. This area was first identified as a conflict ‘hot-spot’ in 2006 and continues to be an area of concern.”

Of note is that Schwartz’s paper, co-authored with Patricia Hernandez, Lisa Landenburger, Mark Haroldson and Shannon Prodruzny, was published in 2012 and explosive levels of exurban sprawl have occurred in the years since, at a higher pace precipitated by the relocation of people to Greater Yellowstone that happened during the Covid pandemic.

Schwartz told me a decade ago that Big Sky was already considered a sink for grizzlies and he recently said in a conversation that all of the escalating development associated with it represents a hazard zone for grizzlies—unfortunate because its located in the middle of a wildland setting that would otherwise be providing exceptional habitat.

Exurban sprawl first creates more conflicts between humans and wildlife, be it animals getting into human foods, or being chased by dogs or causing newcomers to call local state game agencies and demand that wildlife be removed. Eventually, the lack of tolerance for species results in those animals going away. Habitat, however, is finite. Eventually, shrinking habitat supports fewer animals and it can result in the loss of migrations and overall reductions in numbers of animals.

Exurban sprawl first creates more conflicts between humans and wildlife, be it animals getting into human foods, or being chased by dogs or causing newcomers to call local state game agencies and demand that wildlife be removed. Eventually, the lack of tolerance for species results in those animals going away. Habitat, however, is finite. Eventually, shrinking habitat supports fewer animals and it can result in the loss of migrations and overall reductions in numbers of animals.

Servheen says it is remiss of Congress or anyone else, to ignore what is clearly the biggest burgeoning threat to grizzlies. He and others who say counties need to play a more active role in protecting habitat, also note that a grizzly population which in recent years has expanded the limited terrain it occupied 40 years ago could face escalating conflicts from humans expanding their presence in once remote valleys. Sprawl is removing habitat faster than any other cause. He points again to the study by Schwartz et all:

“It is well documented that human caused [bear[ mortality represents the single greatest cause of death in grizzly bears, excluding dependent young, and human developments contribute to this mortality,” Schwartz and co-authors wrote. “Grizzly bears are attracted to human developments in search of food. Unsecured garbage, pet food, bird feeders, livestock and livestock feed are attractants typically identified as the cause of bear-human conflicts associated with developments. As suggested, these areas represent evolutionary traps because the sudden anthropogenic change in the environment results in attracting bears to perceived food source, but the results are maladaptive because of the increased risk of mortality.”

“What we are submitting to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency I worked for, is not a legal threat. It is a good faith attempt to ensure that decisions being made about the future of grizzlies, after so much time and effort have been invested, are based on the best available science,” Servheen said.

Endorsing Servheen’s petition to have the Fish and Wildlife Service pursue a metapopopulation, and not a regionally disjointed approach to grizzly conservation in the Northern Rockies are:

- Dale Becker, former Tribal Wildlife Program Manager, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes

- Kate Kendall, former USGS lead grizzly bear scientist;

- Sterling Miller, Ph.D., former research biologist, Alaska Fish and Game and former President of the International Association for Bear Research and Management;

- Harvey Nyberg, former regional supervisor for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks;

- Mike Phillips, director, Turner Endangered Species Fund and advisor to Turner Biodiversity Divisions;

- Tom Puchlerz, former US Forest Service lead grizzly bear habitat coordinator and Forest Supervisor of the Bridger-Teton and Tongass national forests;

- Chuck Schwartz, Ph.D., former research biologist, Alaska Fish and Game and USGS leader of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team;

- Gary Wolfe, Ph.D., former Montana Fish and Wildlife Commissioner member and former CEO of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and Vital Ground Foundation;

ENDNOTE: This has been a record year for grizzly deaths in Greater Yellowstone. Bears die in many ways. According to the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 85 percent of bears die from human-related causes. Below is the roster of fatalities to date in 2024. Note how many are under investigation, meaning that many deaths are classified as suspicious or worthy of seeing if self defense killing is justified. If grizzlies are delisted, the penalties for illegally killing a grizzly will be weakened, leaving many to believe the number of bear deaths will rise. This does not even include the number of bears that will be getting into conflicts in the years ahead as they enter formerly rural and undeveloped private landscapes undergoing transformation by sprawl.