by Todd Wilkinson

The US Fish and Wildlife Service, America’s top wildlife agency in charge of overseeing imperiled species, announced Wednesday that grizzlies living in the Lower 48 states will not be removed from federal protection under the Endangered Species Act.

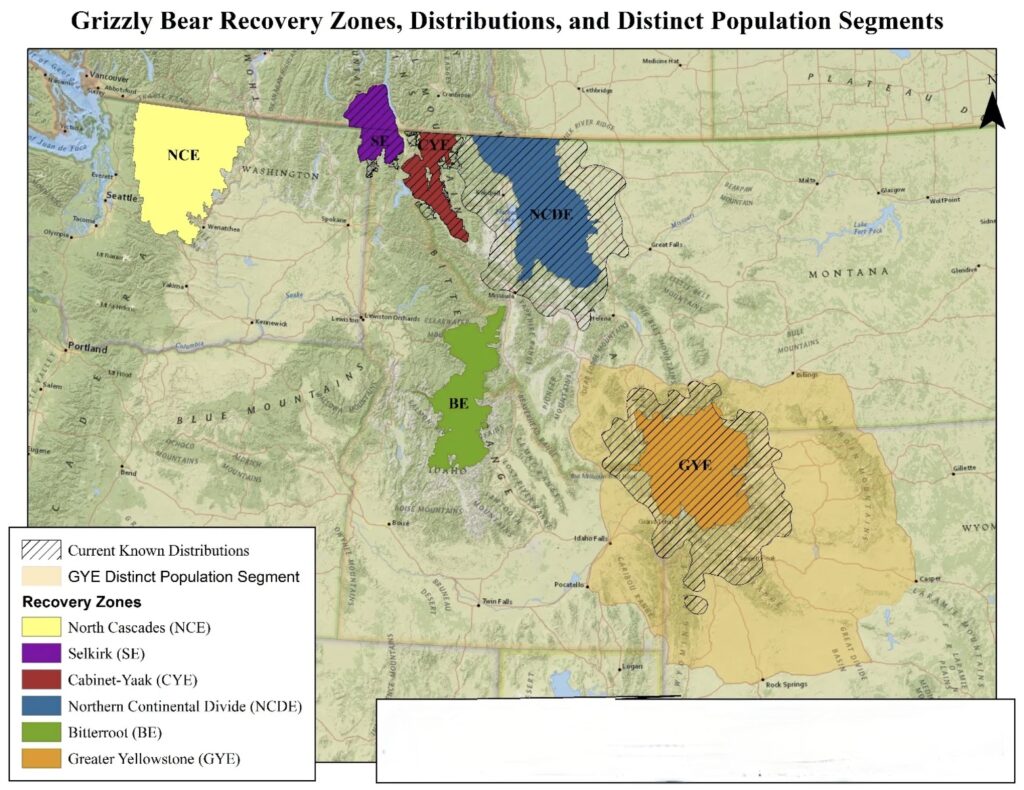

The thrust of the decision, certain to being challenged when the Trump Administration comes into power, focuses on the argument that true biology recovery of grizzlies will not be achieved until current isolated subpopulations of bears are re-connected geographically inside a single mass of bears, called a metapopulation.

Although the agency declined to approve the push made by politicians and others to turn management authority over to western states that have bears living inside their borders, the Service is recommending that states be given greater flexibility in addressing bears that come into conflict with people and livestock. However, one of the lethal tools they can use will not be allowing sport hunters to shoot bears.

No matter where one stands on delisting the announcement will only further inflame the divisive debate over how to best conserve one of the most iconic wildlife species in the world—and how differing special interests interpret science.

“We applaud the Fish and Wildlife Service for following the science and keeping grizzly bears protected. The best-available science shows that grizzly bears are not recovered, and the states have a demonstrated record of failing to manage grizzly bears responsibly. Even with federal protections in place, in 2024 we saw more grizzly bears killed by humans than in any year since their listing 50 years ago, said Drew Caputo, a senior attorney for the environmental law firm, Earthjustice.

In the past Earthjustice has twice represented a coalition of wildlife conservation groups in overturning delisting of grizzlies in court. “Grizzlies face increasing threats, including habitat loss, climate change, and human-wildlife conflicts,” Caputo said. “Stripping them of federal protections now would only raise their death count and threaten to reverse decades of conservation work.”

What the Fish and Wildlife Service essential did was shift away from approaching each isolated group of bears as a distinct population segment and work to stabilize each subpopulation piecemeal. Now the focus, consistent with approaches taken for other species, is to establish a metapopulation that, in order to succeed, would mean having self-sustaining numbers of bears living between the gulf of space separating Greater Yellowstone from the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem.

Each of those ecoregions is believed to have slightly more than 1,000 bears. There are also tiny enclaves of grizzlies in the North Cascades in Washington State, and the Selkirk and Cabinet-Yaak regions of northern Idaho and northwest Montana.

In December Earthjustice filed a petition on behalf of 14 national, regional and state environmental, tribal and animal welfare groups asking the Fish and Wildlife Service to adopt a new approach to recovering grizzly bears arrayed around the metapopulation concept. The petition, supported by Dr. Christopher Servheen who served as the nation’s grizzly bear recovery coordinator for 35 years, details site-specific management actions necessary to aid in the bears’ recovery.

Servheen had actually authored the original grizzly bear management plan for the federal government that has been in effect and which was supported by states. In years’ past, he had supported delisting but reversed his position because circumstances had changed, undermining the premises of his longstanding optimism.

Servheen says that the grizzly subpopulation of Greater Yellowstone is facing increasing private land development pressure that destroys bear habitat and will hasten more human-bear conflict. He also cites hostile legislation to bears being passed by the states, relatively high numbers of bears dying, and impacts from climate change. Bears remain vulnerable, he said, noting that seeking to achieve a large single population would make grizzlies better able to withstand deepening pressures. Read what Servheen said earlier in an interview with Yellowstonian.

Predictably, elected officials in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, livestock interests and hunting organizations, which had hoped to have sport hunting seasons of grizzlies restored 50 years after they were first protected, cried afoul. Claiming that bears have met early-crafted metrics designed to measure recovery, they accused the Fish and Wildlife Service of impetuously altering the roadmap for delisting.

In a statement, Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon wasn’t surprised and characterized it as an 11thhour move by the Biden Administration. He insisted that the shift to say recovery hinges more on establishing a metapopulation than success achieved area by is driven by politics and not biology. “The GYE grizzly bear has been delisted twice,” he said “Population determinations should not be made whimsically; lower-48 management approach is not scientifically based.”

An organization that represents hundreds of ranchers in the West was among the groups that weighed in. “The reality is that grizzly bears are increasing in population and expanding in range well beyond original recovery targets,” said Lesli Allison, Chief Executive Officer of the Western Landowners Alliance. “While grizzly bear recovery is widely celebrated as a success, the moving goalposts for delisting are a source of deep frustration for many in the region. People who live and work in recovery areas continue to experience increasing conflicts, safety concerns and disproportionate economic costs. It is imperative that state wildlife agencies, communities and landowners have both the flexibility as well as the tools and financial resources to manage this growing population and these challenges.”

“While grizzly bear recovery is widely celebrated as a success, the moving goalposts for delisting are a source of deep frustration for many in the region. People who live and work in recovery areas continue to experience increasing conflicts, safety concerns and disproportionate economic costs.”

—Lesli Allison, CEO of the Western Landowners Alliance

A looming question is whether the Trump Administration will use its new incoming, politically-appointed director of the Fish and Wildlife Service to abandon this new approach and whether both branches of Congress will try to legislative fast-track delisting that would result in states bringing back a trophy hunting season on grizzlies.

Tom Mangelsen of Jackson Hole, who has been an outspoken advocate of bear protection and who is known for his photographs of the late Grizzly 399, believes there’s more public support for preserving bears than ever before.

“I obviously am pleased and relieved by the ruling,” Mangelsen said. “Maybe now we can step back for a moment and reflect on what the real goal ought to be. We don’t save species so that one day we can hunt them again for sport. We do it to give them a second chance at survival. That’s a noble objective. Like a human patient who’s been seriously ill, the aim is to help them get well and recover so they can live a long healthy life. Whether bears are delisted or not, they are facing a lot of serious threats, including the mindsets of governors and legislators from Wyoming, Montana and Idaho who seem to think they’re still living in the 19th century.”

“We don’t save species so that one day we can hunt them again for sport. We do it to give them a second chance at survival. Whether bears are delisted or not, they are facing a lot of serious threats, including the mindsets of governors and legislators from Wyoming, Montana and Idaho who seem to think they’re still living in the 19th century.”

—Tom Mangelsen, Jackson Hole photographer and bear conservationist

What’s not in dispute is that the human footprint of development continues to expand markedly in the Northern Rockies, in valleys where grizzlies currently are and whey they likely need to wander to establish solid connectivity between ecosystems.

Increasingly, working lands that previously provided space for many wildlife species are being converted to subdivisions for development, encroaching upon bear habitat and leading to loss of habitat and increased conflicts, said the Western Land Alliance’s Allison. “We’re losing ground—literally—and will continue to do so until we change our fundamental approach to conservation,” she noted. “If we want long-term success, we need solutions that work for both people and wildlife. Things like support for nonlethal conflict prevention practices, habitat leases and fair compensation for losses are needed to alleviate the economic toll on producers in large carnivore recovery areas, enabling them to keep these lands and habitats intact.”

Andrea Zaccardi, carnivore conservation program legal director at the Center for Biological Diversity, was overjoyed by the decision announced by the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Director Martha Williams, who previously had been director of Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks.

With more flexibility given to states to remove bears deemed “problems,” Zaccardi still has questions how it might be implemented. For example, property owners would be allowed to kill bears actively attacking livestock, which means justification will still rely on evidence. In the Upper Green River Valley of Wyoming, federal officials were set to allow for dozens of bears to be legally killed for presenting a threat to cattle on public land grazing allotments managed by the Forest Service. That was overturned.

“While grizzlies won’t be killed by state-sponsored trophy hunts, I’m concerned that their recovery will be harmed as more bears die at the hands of the livestock industry,” said Zaccardi. “We’ll advocate to maintain all protections that keep grizzly bears alive until recovery is reached.”

The two major subpopulations of grizzlies in the Lower 48 are found in Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem which encompasses Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area up along the US border with Canada. In each of those ecosystem there are an estimated 1,000 grizzlies. Meanwhile there are also tiny populations of bears in the North Cascades of Washington, the Selkirk and Cabinet-Yaak mountains of Montana and northern Idaho.

“Now federal agencies should focus on improving connectivity between regions and growing the small grizzly bear populations in the Bitterroots, Cabinet-Yaak and Selkirks,” said Zaccardi. “We know the states can’t be trusted to manage grizzly bears, and ongoing federal protections will keep grizzlies on the path to recovery.”