One of the hardest things for we humans to do is openly challenge the core belief systems that reside among members of our own respective tribes. Which is to say, absorb new facts and allow them to open our minds.

Loyal Democrats struggle as much with this as Republicans do; the same holds for those subscribing to Christianity, Judaism or Islam and the various, sometimes radical, sects residing within each faith.

“If we are this,” we tell ourselves, “then we cannot possibly be that.”

Make no mistake, having the courage to dissent can come with costs, including fear of being cast off the island, but there remains the notion that speaking the truth, as an expression of personal evolution, can set us free.

For years, Carter Niemeyer could feel his moment of liberation approaching but it required that he cross his own Rubicon. Today, looking back, he has no guilt, shame or regret associated with calling out his professional cohorts who still are pushing lethal control of certain wildlife species in the West.

Across more than a quarter century, Niemeyer worked for differing iterations of Wildlife Services, a federal agency most Americans have never heard of. He was tasked with protecting domestic livestock from wolves, coyotes, bears, mountain lions, and even eagles.

Niemeyer’s career literally placed him in the belly of the beast of anti-predator sentiments and he is well versed in every argument that’s ever been made about why the animals above should be destroyed. Most of the portrayals, he says, are based on fairy tales, not facts. No one can refute the hard-earned knowledge he accrued.

° ° °

Not long ago, the Humane Society of the US, an organization largely demonized in Western ranch country, enlisted a polling firm, Remington Research Group, to survey Wyoming residents on what they thought about the now-notorious “Roberts incident.” The case involves a 42-year-old man, Cody Roberts, from Sublette County. See photo of Roberts mugging for the camera with beer in hand.

On Feb. 29, 2024, he allegedly ran over the young wolf with a snowmobile for fun. He later admitted that he wrapped the muzzle of the badly injured animal with duct tape, brought it to a saloon in Daniel, Wyoming to show it off to bar patrons and then killed it. Read the Yellowstonian report about that and its aftermath here. While state officials claimed that what Roberts did was an isolated event, it was hardly the first time people in that part of Wyoming engaged in such activity on snowmobiles. I wrote an investigative report about it in 2018 and still have video recordings of others showing off as they brutally ran down coyotes.

What Roberts and others did in Wyoming, a reality shocking to the world, was perfectly legal. Some 71 percent of Wyomingites who were surveyed by Remington Research said they believed Roberts’ actions qualified as animal cruelty. In addition, 57 percent said laws, which currently allow wolves to be killed by almost any means in 85 percent of Wyoming, need to be reformed.

Looking at the poll a different way, the results also reveal that 16 percent of those surveyed did not see the Roberts incident as constituting cruelty and 13 percent said they weren’t sure. That’s more than a quarter of respondents.

Regarding the need to amend existing laws, 30 percent of those surveyed said no changes are necessary and 13 percent indicated they are undecided. That’s almost one half.

To Niemeyer, the results are not encouraging but problematic. They suggest that Wyoming has a long way to go because it appears hatred toward certain wildlife species is still deeply engrained in its culture. Worse, the fact that elected officials in the state capital of Cheyenne refuse to fix the problem illustrates “a level of depraved thinking that ought to leave them ashamed. If this is how they allow wildlife to be treated, then how does that reflect their character in so many other areas?” he asks.

Niemeyer believes politically-driven assertions made about carnivores in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho— toward wolves especially and with little scientific basis supporting the negative contentions—have turned professional wildlife management in those states on its head. Continuously repeating untruths and mistruths about wolves, grizzlies, coyotes and other species, and even yelling those claims at the top of one’s lungs, may be tribally cathartic, Niemeyer says, but it does not change the natural history of those species.

A lanky farm kid from Iowa by origin, Niemeyer, who stands 6’5” tall, grew up hunting, fishing and trapping. “I was a hardcore trapper,” the 77-year-old who now lives in Idaho, says. “I loved it and I like to think I was pretty good at it. I must have been, because that’s why I was recruited to do what I did.”

After earning two degrees from Iowa State University, Niemeyer moved West in the 1970s. His trapping skills were put to use on behalf of livestock interests who often turned to Wildlife Services, a division within the federal Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service which is itself an agency inside the US Department of Agriculture.

Quickly, Niemeyer gained a positive reputation among ranchers and farmers for being very good at fulfilling his primary duty: killing wildlife that represented a perceived threat to cattle, sheep, chickens and other domestic creatures. He carried on a tradition brought to the West by settlers and which had been imported from Europe—and it resulted, by the mid 20th century, in the decimation of many native animals labeled a threat to non-native livestock. “We destroyed our natural heritage on millions of acres of the West in order for people to raise cattle and sheep,” he says. “We destroyed bison because they were perceived to be competitors to grass and then we annihilated wolves, grizzlies, black bears, mountain lions and coyotes—millions of animals in total—because someone determined that no loss of livestock was acceptable.”

Quickly, Niemeyer gained a reputation for being very good at fulfilling his primary duty: killing wildlife that represented a perceived threat to cattle, sheep, chickens and other domestic creatures. He carried on a tradition brought to the West by settlers and which had been imported from Europe—and it resulted, by the mid 20th century, in the decimation of many native animals labeled a threat to non-native livestock.

Niemeyer conducted his work on both private and public land. The tools of the trade, sanctioned by his federal employer, were: leghold traps, body-crushing conibears, snares, poison baits including devices that dispense ultra-toxic sodium cyanide, and small aircraft and helicopters enlisted foremost for aerial gunning of coyotes.

Niemeyer himself never deployed sodium cyanide but he was taught how to use it. By his own estimate, he killed thousands of coyotes and foxes, plus 14 wolves. “I have their blood on my hands,” he said. (Later, when he went to work for the US Fish and Wildlife Service after he had an epiphany, he captured more than three dozen wolves and relocated them live, including a few that today are ancestors of current Yellowstone wolf packs).

Between 1987 and 2002 , the Fish and Wildlife Service reported that 117 gray wolves were relocated in the Northern Rocky Mountain Region. Niemeyer was involved in the capture and relocation efforts of many of those wolves. “After 2002, [the Fish and Wildlife Service’s national wolf recovery coordinator] Ed Bangs decided that relocation was no longer an option. From then on, problem wolves were killed, or I could have saved a few additional wolves from destruction,” Niemeyer shared.

° ° ° °

It was—and still is— common practice for Wildlife Services to, instead of waiting to be summoned, to pre-emptively head into an area at the invitation of ranchers to kill as many coyotes as possible—even if they are causing no “predator problems.” Bureaucrats with the agency have described that as “prophylactic” killing. Niemeyer calls that absurd. “The idea is that you go in and wipe out coyotes or wolves to prevent future losses that won’t actually occur,” he says. “It’s kind of like clearcutting a forest to prevent it from burning.”

Niemeyer knew who buttered his bread. His salary, performance evaluations and continued employment were based upon having an adequate budget and budgets grew if field personnel like him continued to rack up annual death tolls, which also kept ranchers, and the politicians who answered to them, happy, he said.

“Our orders were clear. Wildlife Services sounds like an agency that is there to be an advocate for wildlife. Most of the time it was just the opposite. We were there to serve the interests of stockgrowers and woolgrowers whom we referenced as ‘our customers,’” he said. “Our primary clients were not the wildlife-loving public of America who were actually footing the bill.”

“Our orders were clear. Wildlife Services sounds like an agency that is there to be an advocate for wildlife. Most of the time it was just the opposite. We were there to serve the interests of stockgrowers and woolgrowers whom we referenced as ‘our customers.’ Our primary clients were not the wildlife-loving public of America who were actually footing the bill.”

—Carter Niemeyer

What neither Niemeyer and fellow trappers, nor his clients fully realized in the prime of his killing years, is that because of coyotes’ ability to reproduce, annihilation campaigns often backfired, making predator conflicts worse rather than better. What the public still doesn’t realize, he notes, is that taxpayers have spent hundreds of millions of dollars subsidizing private livestock protection and a lot of public wildlife was and are being killed, he said, that didn’t and don’t need to die.

° ° ° °

According to Lizzy Pennock with WildEarth Guardians, a conservation group, Wildlife Services, Niemeyer’s former employer, killed 56,089 coyotes in 2022, along with 26,371 beavers, 2,432 foxes, 515 bobcats, 450 black bears, 219 gray wolves, 205 mountain lions, and seven federally protected grizzly bears, among many other species. If a conflict erupts, for example, between grizzlies and cattle on public land in the Upper Green River country of Wyoming, it has been Wildlife Services that intervenes and its unspoken priority, he says, is making the range safe for cows, not bears.

Wildlife Services in 2022 also gassed over 200 coyote burrows and dens, killing an unknown number of pups. That toll above is just the number that was officially reported and does not include the tens of thousands of coyotes killed in the West by civilians because, basically, no justification is necessary and in many states it’s open season. In 85 percent of Wyoming, right now, it’s legal to do the same with wolves.

The 2022 Wildlife Services report also revealed that field personnel working for the agency killed 2,631 animals “unintentionally” in a single year. That includes domestic pets. Over the years imperiled wolverines, Canada lynx and others have died from traps and poisons. Today, there is the real possibility, he notes, that in coming years grizzly bears and cubs likely will die from snares, set by Wildlife Services or private trappers trying to kill wolves.

After years of destroying predators, Niemeyer left Wildlife Services and became the wolf recovery coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Idaho and he also worked in Montana. “I was personally involved in the live capture of perhaps 20 grizzlies and all but one were relocated either by me as an authorized Wildlife Services employee through the Fish and Wildlife Service or via state oversight and assistance,” he says. “I was involved in one control action where we killed a grizzly bear for killing sheep.” (Note: If bears are delisted, both Montana and Wyoming have indicated they may halt re-locating grizzlies to give them another chance at survival if they have conflicts with humans or livestock).

Still possessing a network of contacts inside federal and state agencies, Niemeyer says from his home in Boise there’s solid evidence for criticism of Idaho’s “wolf annihilation campaign” and if Americans knew what is happening, most would be shocked.

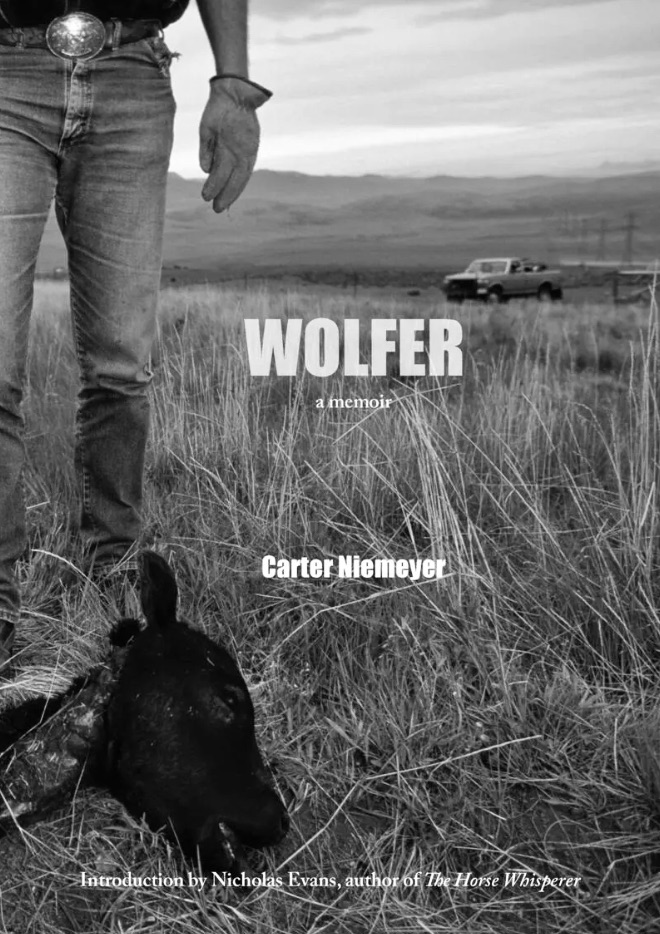

Upon his retirement, he wrote two tell-all books that earned him praise and also accusations of cultural betrayal, including thinly-veiled threats that he needed to keep his mouth shut.

Wolfer: A Memoir and his second book, Wolf Land, bring readers to the front lines of the West’s predator war and explain the events that caused him to suffer a crisis of conscience.

Over time, the reality of his field work with Wildlife Services started gnawing at him, he says. Predator control in the West is touted almost with religious conviction and Niemeyer says the evidence he gathered daily, which contradicted the assertions made by people who hate predators, shook his own long-held beliefs to their core. Like the soldiers at My Lai who carried out orders from their commanders in Vietnam and took part in atrocities on civilians, Niemeyer says he and many of his colleagues wrestled with the question of what does one do when superiors tell you do things you know are morally and ethically wrong?

“In the beginning, I was zealously committed to what I did because it was kind of an extension of my own rural cultural upbringing. But then I became super aware and conscious of my own misguided notions when I started seeing what we were doing to these sentient beings,” he says. “It bothered me a lot—inflicting pain and misery on these animals and being rewarded for it. Some of my colleagues seemed to really enjoy it. When I started raising doubts about what we were doing, I was labeled a traitor though many others quietly agreed with me. Some either left the agency or they wouldn’t speak up because they were afraid of losing their jobs. Predator control is built on a culture of secrecy because that’s how you avoid scrutiny.”

Niemeyer wasn’t the first whistleblower. A generation earlier, Dick Randall, who worked for Wildlife Services’ predecessor, Animal Damage Control, had been a predator control specialist in Wyoming and exposed what he said were illegal activities carried out by federal and state agencies. He wrote this piece in 1991 and in 1976 he was featured in a profile written by Bruce Hamilton that appeared in High Country News when that publication was based in Lander, Wyoming.

“In the beginning, I was zealously committed to what I did because it was kind of an extension of my own rural cultural upbringing. But then I became super aware and conscious of my own misguided notions when I started seeing what we were doing to these sentient beings. It bothered me a lot—inflicting pain and misery on these animals and being rewarded for it. Predator control is built on a culture of secrecy because that’s how you avoid scrutiny.”

Like Randall, Niemeyer noticed a disconnect between anti-predator rhetoric voiced even in the halls of Congress and with what he found as a principal forensic investigator tasked with identifying why cattle and sheep went missing or what is alleged to have killed them. “We’d be called to a ranch where a dead cow was lying in the mud and there were no wounds from canid teeth or other telltale signs and no tracks of wolves, coyotes, bears or mountain lions,” he said. “And I’d look at my partner and remark, “I’ll bedamned, another amazing example of stealthy predators who must have flown through the air and killed the cow or sheep without taking a bite. There seems to be a lot of these.”

Right now, the livestock industry in Colorado is going through the same melodramatic gyrations that states in the Northern Rockies did after wolves were reintroduced in the 1990s, he says. They are predicting an apocalypse with wolves that isn’t going to happen. Ranchers show up at meetings shouting and trying to intimidate anyone who challenges what they say, but their “rampant exaggerations and lies” need to be called out, he says.

To make his point, Niemeyer cites what he describes as deceptive statistics circulated by government agencies and politicians. He is not unsympathetic to ranchers and farmers who suffer real loses of livestock to predators and in those instances the government is very effective in solving the problem, but losses need to be considered within context.

“When you look at actual losses caused, for example, by wolves, they account for .009 percent of cattle and sheep losses. Yes, you heard that right—point zero zero nine percent. Often we hear people say, ‘Well, what about the cows and sheep that are killed by wolves and never found?’ And my response is, ‘Well, okay, go ahead and triple the number of reported cattle and sheep deaths attributed to wolves. Add that up and it doesn’t even get you to one percent of total losses.”

On a top 10 list of threats to ranchers’ economic viability, Niemeyer says bad weather, eating poisonous plants, disease and digestion issues, animals getting injured through accidents, getting washed down streams, falling off cliffs, lightning strikes, predation by roaming domestic dogs and others kill more cattle and sheep than predators. On top of that, ranches and farms are confronting true existential challenges from market economics, ag kids going away and not wanting to come home to run the family operation, and sprawl making it harder to achieve scale.

A disproportionately large percentage of resources are focused on lethal predator control, he says, because villainizing predators—blaming them for any hardship—creates a convenient scapegoat and a rallying cry for defiant cultural behavior. “If you’re frustrated in life, you want to point a finger at something, so you claim all the problems in the world are owed to predators even if it’s not true,” he says. “Wolves do not, as many believe, kill everything in sight, destroy their own food supply, or lick their chops at kids waiting at bus stops. They are simply predators like lions and bears, and anyone who believes otherwise is, well, wrong.”

For decades, Niemeyer has been an avid elk hunter and he says that people who claim they haven’t been able to get a wapiti are either not trying hard enough or are not very skilled at hunting. “In Idaho, Wyoming and Montana, it’s really not that hard to get an elk, and the same holds true with white-tailed deer in the Midwest where I grew up and where there are wolves,” he says.

Today, there are more elk in Northern Rockies states than at any time in the last 140 years, according to the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and state game agencies. Niemeyer points out that as wolf numbers rose following their re-introduction in 1995 to Yellowstone and central Idaho, so too have the size of most elk herds to the point where states claim there is “an overabundance.” Ranchers are complaining about elk numbers, and so, as a response, states have implemented aggressive hunting seasons to reduce their numbers. “Elk populations are chronically over objective in most hunting districts around the state,” claims the United Property Owners of Montana. “The 2020 elk counts put statewide population around 170,000 animals. Populations are over objective in 77 of the 105 districts counted.”

In addition, Niemeyer says, predator control campaigns continue to be waged at the same time Chronic Wasting Disease is rapidly spreading in elk and deer populations. Researchers say that having healthy populations of wolves, bears, mountain lions and coyotes could help slow the spread of CWD that is projected to dramatically reduce elk and deer populations over time and it represents a potential danger in spreading to humans who eat game meat.

In 2017, a peer-viewed analysis published in the Journal of Mammology attempted to gauge public opinion toward predator control. It was authored by Kristina Slagle, Jeremy T. Bruskotter, Ajay S. Singh and Robert H. Schmidt.

Researchers contrasted what people thought in 1994 vs. 2014. Support for killing wildlife to protect livestock, they found, is partially based on this sentiment from average Americans: “Wildlife control is acceptable if there is evidence that wildlife damage is the cause of economic loss.”

“The support for predator control represents a pragmatic side of the public; there is general agreement that wildlife causing damage to livestock or crops, or causing economic loss generally, may be subjected to actions designed to prevent or eliminate the problem,” authors of the study note. “Currently, support for predator control is substantial despite the fact that only a small percentage of respondents reported experiencing wildlife damage in the past 5 years (13 percent), and only a little more than one-third (37 percent) reported having ever hunted. These data support the conclusions of researchers who contend that individuals will generally support lethal management of predators if such actions are undertaken to address what individuals perceive as legitimate impacts.”

“Legitimate impacts” is term that states and the livestock industry deliberately keep vague. A wolf may kill a few calves or sheep, Niemeyer says, and it creates headlines in newspapers but what isn’t mentioned in stories is that hundreds of animals died in the same area from other non-predator causes.

“That never makes the news. I don’t know of a single ranch or farm that went out of business due to losses of livestock from predators yet the perception persists and part of the blame for that is owed to sloppy journalism that either misrepresents the facts or doesn’t hold the people perpetuating the myth to account,” Niemeyer says.

There is paltry evidence, at best, he adds, that allowing wolves “to be persecuted” engenders more social tolerance and respect for the animals. “After being in the predator business, I can tell you it doesn’t change anything. Allowing people to wantonly kill predators just motivates them to do more of it,” he says. “The more socially acceptable it is, and if intolerance is legalized, the more they take advantage of it. The Roberts case represents just the tip of the iceberg of attitudes that justify what he did. He ought to be treated with the same kind of scorn that we hunters have for those who poach trophy elk or people who starve their horses.”

There is paltry evidence, at best, that allowing wolves “to be persecuted” engenders more social tolerance and respect for the animals. “After being in the predator business, I can tell you it doesn’t change anything,” Niemeyer says. “Allowing people to wantonly kill predators just motivates them to do more of it. The more socially acceptable it is, and if intolerance is legalized, the more they take advantage of it.”

As a retired trapper, Niemeyer says there’s no compelling market argument either for having trapping seasons on most species. A recent review of the fur market at the website, Trapping Today, notes that in 2024, beavers in the West were bringing in $31 per pelt, otter $33, muskrat $2, wild mink between $12 and $16, and red fox $16 to $17. That’s less than a fry cook working at McDonald’s makes in an hour.

Bobcat prices rose in 2024 but in recent years pelts have yielded around $350. Fur buyers earlier this year were paying $57 for fisher and $50 for marten. While lynx and wolverine are protected in the Lower 48, in Canada and Alaska pelts from those animals fetched $140 for lynx, $400 for wolverines, and between $150 and $500 for wolves.

“You have to kill a lot of animals to cover your time, gas and other expenses. With fur prices so low, it means trappers aren’t doing it for the money; they’re doing it for fun, which means it isn’t necessary to their survival,” Niemeyer says. “At the same time, in the Lower 48 where there are only a few hundred wolverines and low numbers of lynx and grizzlies, a species which has a low reproductive rate. Losing those animals to trapping can negatively affect the survival of those species. Very few people, if any, make their living on trapping. I know because for many years I supplemented my income as a trapper.”

Niemeyer says he believed the 21st century had the potential to usher in a new era of more thoughtful, science-driven wildlife management. But people who devoted their careers to working for state agencies have opted for early retirement or are fleeing them because of how politics has co-opted decisions being made. Wildlife Services, to its credit, is investing more in non-lethal management, but the ag lobby, combined with state legislatures that have enacted regressive anti-predator policies, are blunting the progress.

“There was a time when I had faith that leaders in these states had evolved but instead they just pander to mythology and the people electing them are ignorant and gullible,” Niemeyer says. “If people are in an uproar over what’s happening with wolves, just wait until grizzlies are delisted and the states apply the same attitudes to bears. We are on a path leading to the bad old days.”

Were he called to testify on Capitol Hill or in the state capitals of Boise, Helena and Cheyenne and were this reformed former trapper allowed to speak the truth to senators, members of Congress, governors and legislators, this is what he’d say:

“I’d put it bluntly. I just don’t feel the states at present have the maturity to manage wildlife responsibly. You see it with Montana’s backward attitude toward Yellowstone bison and it’s apparent especially with grizzlies and wolves in the three Northern Rockies states. State game managers, who might otherwise want to do the right thing are under the thumb of politicians and influential members of the livestock industry who want to severely control bears and wolves,” he said. “As we’ve seen with the Roberts incident in Wyoming, state game officials, even if they wanted to, are forbidden from exercising good judgment and speaking out against cruelty and torture they know is wrong. They’re not even allowed to say the laws need to change and, as wildlife professionals, they don’t have the courage to say they support these changes. But at the end of the day they will have to live with themselves and know they deceived not only the public who paid their salaries but they deceived their own moral and ethical principles. To me, that’s not just sad; it’s pathetic.”

Subscribe

Never miss a story, subscribe to our newsletter!

Support Yellowstonian and

Get Some Real Cool Visual Stuff

From now through the end of July, Livingston-based Artemis Institute, the parent non profit entity of Yellowstonian, is participating in the Park County, Montana Community Foundation’s Give a Hoot fundraiser and all contributions made to Artemis Institute will support Yellowstonian‘s mission of providing conservation journalism focused on Greater Yellowstone. We would be profoundly grateful for your support and here’s your chance to get a really cool visual reward for your generosity: Anyone who contributes $35 or more will receive their pick of one individual species poster below or all three for $100. For a donation of $350 or more, supporters will receive a special, limited-edition collector’s lithograph that features all three of Greater Yellowstone’ species’s icons. It is hand-signed by Eric Junker.