by Gregory Nickerson, Biographer of Mule Deer 255

We have some sad news to share. After 11 years, the Wyoming mule deer that migrated farther than any other deer known to science has died. Deer 255’s life of migrations ended in the Red Desert of Wyoming, about 200 miles from her most recent summer range in Jackson Hole. She was 10 years and 10 months old.

The death marks the final chapter in the life of a remarkable mule deer whose story has captured the hearts of millions of people around the world, and helped to share the science of mammal migration in the American West.

Born in June 2013, Deer 255’s life spanned a significant period in the field of migration science and conservation. Her lifetime saw Wyoming map and designate its first migration corridor in 2016, and ended at a time when 182 migrations had been mapped across 10 western states.

Biologists designated her Deer 255 because she was the 55th animal collared in the second year of a collaborative study led by Matthew Kauffman at the U.S. Geological Survey Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and the Monteith Shop at the University of Wyoming, with strong collaboration from the Bureau of Land Management – Wyoming and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

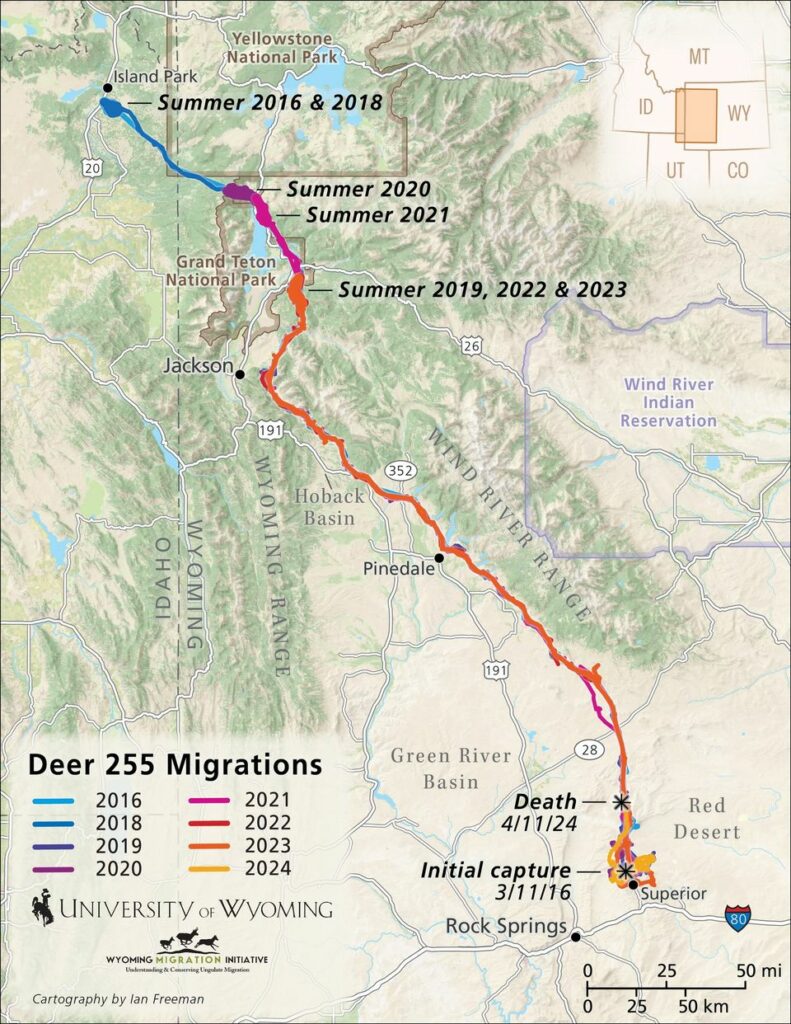

Biologists first captured Deer 255 on March 11, 2016 in the Leucite Hills near Superior, Wyoming where she spends winter. University of Wyoming PhD student Anna Ortega and the research team were astounded in June 2016 when Deer 255 — having already migrated 150 miles to the Hoback Basin — broke off from the rest of her herd and migrated an additional 90 miles to Idaho.

Deer 255’s walkabout ran from Bondurant, Wyoming and skirted Cache Creek above the town of Jackson. From there she traversed the shoulder of Jackson Peak and crossed the Gros Ventre River east of Slide Lake. She passed near Moran Junction and less than a mile from Jackson Lake Lodge, then bounded over a highway to traverse the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway.

After swimming the Snake River near the inlet of Jackson Lake she climbed over the low north end of the Teton Range, then forded the Fall River in the southwest corner of Yellowstone National Park. Her final 2016 summer range was four miles from Island Park, Idaho, 242 miles from where she started (see map).

At the time, no deer had migrated such a great distance from winter range to summer range. Across North America, only Arctic caribou are known to migrate farther.

Ortega and the team could not yet tell if this incredible movement was a true seasonal migration or a dispersal event. Before they could observe her fall 2016 migration to confirm if she would return to the Red Desert, Deer 255’s GPS collar malfunctioned on August 7, 2016.

Deer 255’s whereabouts were unknown for the next 19 months until March 12, 2018. That’s when Ortega and crew were recapturing study animals on their Red Desert winter range near Superior, Wyoming. The helicopter pilot spotted a deer on Steamboat Mountain with a brown GPS collar that they could see but not hear on the radio. They captured the doe, and Ortega — with a quick glance at the collar serial number etched into her memory — immediately recognized her as the long-lost deer.

From that point on biologists had an unbroken record of migration data for Deer 255, during which they tracked her nearly 3,300 miles across seven spring and seven fall migrations. Her migration tied together a vast swath of Wyoming and Idaho spanning private working ranches and public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management, the US Forest Service, and the National Park Service.

And then, Deer 255’s vast yet incredibly regular movements ended in a patch of sagebrush. She died three days into her 2024 spring migration, having traveled about 16 miles north from her Leucite Hills winter range straddling the Continental Divide near Superior, Wyoming.

She died around the noon hour on April 11, 2024, according to GPS collar data monitored by current University of Wyoming PhD student Luke Wilde.

Wilde and I found Deer 255 five miles north of Steamboat Mountain, a volcanic uplift near the Killpecker Sand Dunes in Sweetwater County. This area is an important spring migration stopover for Red Desert mule deer.

In the modern West where deer often die by disease, habitat loss, starvation, fence entanglement, or vehicle collisions, Deer 255 died playing her role as a prey animal in an intact ecosystem.

In the modern West where deer often die by disease, habitat loss, starvation, fence entanglement, or vehicle collisions, Deer 255 died playing her role as a prey animal in an intact ecosystem. Although mule deer display extreme fidelity to their migration routes year after year, Deer 255 was notable for her ultra-long distance migration.

Signs on Deer 255’s body suggested predation as the probable cause of death, most likely a mountain lion. Several scavengers visited the remains, including a golden eagle, magpie, mouse, and a ground squirrel, as documented by motion-triggered cameras set up by the researchers.

Deer 255 was healthy as of March 12, 2024, when last captured for a field checkup. She was pregnant with twins and had a body fat percentage of 6 percent, which put her in the top 12 percent for all animals that spent the past winter near Superior.

As a long-distance migrant, Deer 255 typically had more body fat than medium or short-distance migrants that winter in the Red Desert but migrate to the southern Wind River Range or Steamboat Mountain, respectively.

She also had a larger body size than average — 170 pounds compared to most female mule deer at around 140 pounds — and a notched left ear from an unknown injury. Throughout her life she had crossed highways dozens of times and jumped more than 1,000 fences. No doubt she had avoided numerous predators, just as she had eluded field biologists trying to spot her in the field, which earned her a reputation as the wiliest deer in the study.

The long-term research project focuses on the migration dynamics of the deer that winter near Superior and make the Red Desert to Hoback migration. Biologist Hall Sawyer with Western EcoSystems, Inc. initially documented this 150-mile mule deer migration in 2014. The State of Wyoming officially designated the broader Sublette Mule Deer Corridor was as “vital habitat” in 2016.

Although mule deer display extreme fidelity to their migration routes year after year, Deer 255 was notable for her ultra-long distance migration.

Deer 255 summered in different spots over the years, but she always used the same exact migration route to get there and back. Ortega tracked Deer 255 across the full 242-mile migration from the Red Desert to Island Park, Idaho in both 2016 and 2018. In 2020 and 2021 Deer 255 spent the summer near Mt. Berry and Mt. Reid near Jackson Lake, Wyoming, both known locations along her past routes to Idaho.

With mule deer populations across the West down by 40 percent in the past two decades — and a global decline of migratory ungulates across the planet — conservation of migrations is key to sustaining productive herds.

For the summers of 2019, 2022 and 2023, Deer 255 spent the summer in the Bridger-Teton National Forest in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Those years she foraged and nursed her young in habitats 14.5 miles east of the summit of Grand Teton, near Dry Lake and the Triangle X Ranch.

Using field ultrasounds in 2016 and 2018-2024, biologists documented Deer 255 had eight pregnancies, including seven sets of twins.

Both Ortega and Wilde attempted to collar an offspring of Deer 255 to see if one of her fawns would learn her long migration and carry that knowledge forward for another generation. Despite her multiple successes in bringing twin fawns to winter range in the Red Desert, biologists were unable to track any of her fawns migrating back to summer range.

Researchers suspect that other deer make Deer 255’s record-breaking migration, but her specific migration tactic is rare and has yet to be recorded in any other collared deer.

Of the hundreds of animals tracked in the Red Desert, only one other deer has been known to migrate to Idaho: Deer 665 spends the summer on Teton Pass and made an exploratory movement to near Ririe, Idaho in 2022. The Wyoming Migration Initiative will continue to publish updates about Deer 665’s migrations on social media.

As of this writing, Deer 255’s distance record for mule deer still stands, though biologists expect it will be broken as migration tracking efforts continue across the West.

Deer 255’s story attracted substantial interest from the public. Animations of her migrations were viewed 3.75 million times across four videos published on social media by the Wyoming Migration Initiative from 2019 to 2022. Journalists featured her in numerous stories by High Country News in 2018 and 2024, the Casper Star-Tribune, Cowboy State Daily, Wyoming Public Media, and others.

Deer 255’s life story was further highlighted in an interactive geonarrative published by the USGS demonstrating how collaborative projects have helped conserve migrations in Wyoming, which has the some of the most-intact migration corridors in the lower 48 states.

About 1,800 mule deer live in the Superior segment of the Sublette mule deer herd, which was estimated at 26,000 deer in 2023. Remarkably, the deer that winter in the Red Desert had 80 percent survival in the severe winter of 2022-2023, faring significantly better than other herds in western Wyoming.

The use of long-distance migration strategies to connect excellent summer range to low-elevation winter range is thought to give the Red Desert deer optimal fat gain over summer and fat conservation during winter that confers a survival advantage.

From a conservation perspective, migrations of all distances help animals survive in the highly-seasonal habitats of the Rocky Mountains. Migration is a behavioral adaptation shared across many terrestrial ungulate species, known to Native Americans for millennia.

In many parts of the West, the animals themselves are revealing the true scale of migration connectivity and habitat requirements. In response, state and federal agencies, nonprofits, and landowners have come together to manage migrations over the long term as landscapes continue to change.

With mule deer populations across the West down by 40 percent in the past two decades — and a global decline of migratory ungulates across the planet — conservation of migrations is key to sustaining productive herds. For this reason, the Wyoming Migration Initiative at the University of Wyoming has been sharing Deer 255’s story since 2018 to increase public understanding, appreciation, and conservation of large mammal migrations.