by Kris Ellingsen

On April 9, 2025, at the beginning of the forum in Bozeman, Montana, titled Loving Our Wild Backyard: How Can We Save the Mini-American Serengeti?, panel moderator and journalist Todd Wilkinson posed a question along the lines of: “Why don’t we protect wildlife migration routes the same way we protect our rivers?”

Actually, I wondered, do we really reverentially safeguard our rivers in Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies?

I live near the Gallatin River, downstream from Big Sky, and what I refer to as Yellowsnow Club. Consequently, my concept of river “protection” is clouded; let’s say it carries with it some turbidity, some traces of algal bloom. But Todd’s question keeps flickering in the back of my mind, so I’ll take a turn at entertaining it.

Here’s a somewhat obvious response: We, Homo sapiens, are a species that relies on vision, and rivers are usually in full view. In addition, we have a long history with rivers including drinking from them, navigating them for necessity or fun, watering our crops with them, bunching them up and then pouring them over precipices to harvest their energy, and appreciating—sometimes capturing, killing, and eating—the other species that live in or near watercourses.

Sure, many people value rivers for their own sake, but perhaps a large part of our desire to protect them is based in our human needs, perceived or real. The less obvious response is that migration routes are often nearly invisible. They’re ancient trails that meander and change to some degree. They’re paths etched on the earth by species that rely on scent, taste, touch, and hearing much more than we do.

Migration routes are about species survival, so their paths could be expected to be subtle, relatively unseen and silent efforts to avoid encounters with key predators, of which we comprise one big, noisy category.

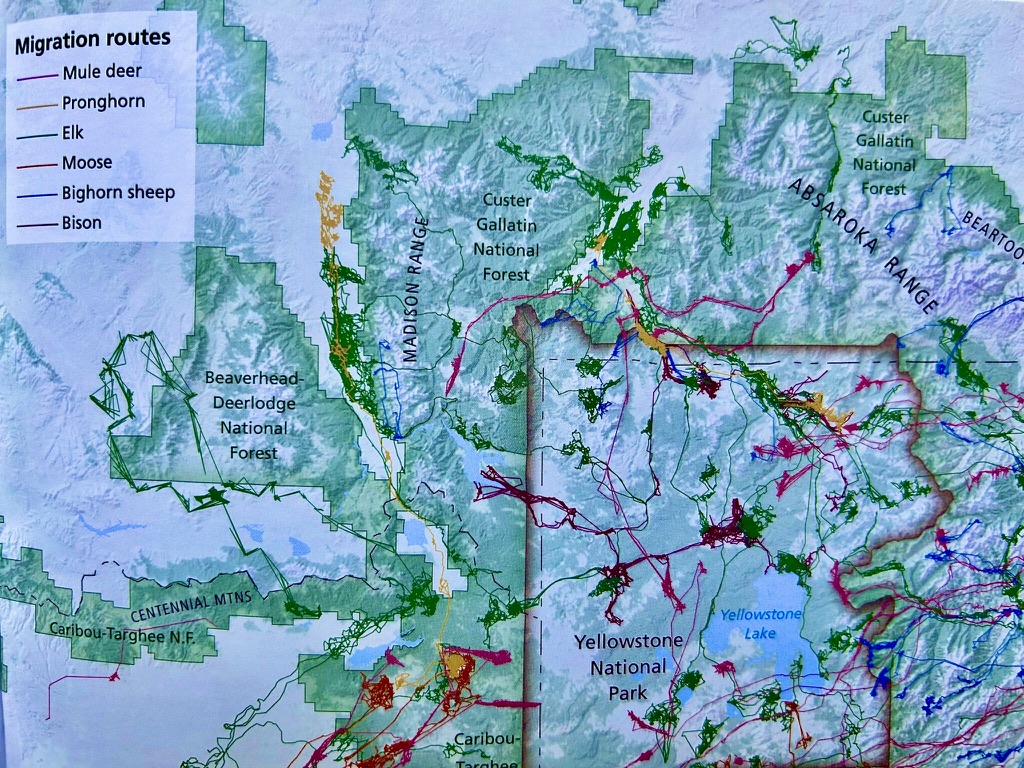

Wyoming is amassing an admirable track record for mapping and paying attention to migration corridors, for species such as pronghorn, mule deer and elk. The Wyoming Migration Initiative is an international leader. Other states like Montana have lagged behind.

Perhaps we don’t protect wildlife migration routes as we do rivers because we’re mostly oblivious to them. (I speak here as a middle-class white woman and a Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem native who grew up in a culture of outdoors appreciation that did not include hunting.) And it’s bigger than that; we have a chronic myopic condition: relentless speciesism.

Perhaps we don’t protect wildlife migration routes as we do rivers because we’re mostly oblivious to them. (I speak here as a middle-class white woman and a Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem native who grew up in a culture of outdoors appreciation that did not include hunting.) And it’s bigger than that; we have a chronic myopic condition: relentless speciesism.

We undervalue the sentient, mysterious and inherently singular lives of these wild others who create the routes. We don’t “see” the other species. Unless of course, their needs cross ours. Then we pay attention.

On Easter Sunday, I wasn’t paying attention. I almost hit a deer with my car. I was driving, slowly enough, on a quiet road near the north foothills of the Gallatin Range, but I was distracted by a notebook on the empty passenger seat beside me. Suddenly a doe appeared on my right. I was startled to see the arc of her form as she leaped across a fence, and then all at once, she was right in front of me.

I saw her graceful body, cantilevered in mid-stride, leaning out from under my front bumper as I swerved and braked to avoid hitting her. It all seemed instantaneous, but of course, that wasn’t exactly the case. Her route was simply perpendicular to mine, and had I been looking more carefully to either side of the road—where fenced pastures colored ochre and grey in mid-April camouflaged a small herd of white-tailed deer in their late winter pelage—she would have had plenty of time to cross.

The only truly sudden thing in this situation was the transformation of my obliviousness into panic.

I live with low-level dread about this while driving. I feel acute anguish when I see any animal dead by the side of, or in, the road. And once, when I saw a pickup truck run over the back half of a marmot, mortally wounding but not killing it, I felt a black ragetoward the callousness of this driver who couldn’t be bothered to stop. And about the stupidity of the misery we cause on roadways? I sometimes feel despair.

In Montana, approximately 200 people die in car accidents each year, and these tragic fatalities are marked with white crosses by the side of the road. Near my home, the mouth of the Gallatin Canyon is a particularly dangerous nexus, where fatalities and serious injuries occur due to collisions with large ungulates attempting to cross US Highway 191. Numbers are hard to pinpoint, but at least seven people died and 27 were badly injured between 2009 and 2018. (Editor’s note: Read the recent study produced by the Bozeman-based Center for Large Landscape Conservation).

And large ungulate deaths during those years? Probably about 2,300 (my extrapolation from data published from the March 20-April 2, 2025 issue of Explore Big Sky).

What to do, especially while we are waiting for more wildlife over-and-underpasses to be funded and constructed? (The “Animals’ Bridge” on Highway 93 in Montana—a collaboration between the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes working together—is a good example of what is possible.) The data concerning the effect of human sprawl and motorized travel on migration routes are widely available from various organizations [see, for example, the Department of Transportation for Montana and Wyoming, the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, the Craighead Institute, the work of Dr. Patricia (Patty) Cramer, to name only a few].

But we, the visual species, have a poor track record about changing our collective behavior in response to written expression. OK then, maybe we need it made loud and clear, but not in words.

While traveling in Norway last autumn, I was delighted to see artist Linda Bakke’s Storelgen (“The Big Silver Moose”), an enormous stainless steel sculpture that stands alongside National Highway Number 3 near Atna. Storelgen has two jobs: he stands over a park where people can stop for a break from driving, and he also alerts folks to be on the lookout for moose crossing the road. Maybe he could be cloned. He’s hard to miss.

And maybe we could pick up on the Montana tradition of placing small white crosses to mark highway fatalities. Human deaths, that is. What if we similarly planted a red cross at the location where each non-human animal died? The number of crosses would be truly sobering—probably more than 4,000 for the mouth of the Gallatin Canyon, just for ungulates alone given the toll over time—and that’s the idea.

I am inspired to discover that there are pioneers in the niche of wildlife-honoring signage, activists and artists including Bram Koese, who installed crosses to mark non-human animal deaths, and L. A. Watson, whose roadside animal cutouts are species specific and use reflective tape for visibility during the dark hours. I applaud their practical and visionary work.

It won’t resurrect the people or the countless non-human animals who have already died, but perhaps such efforts could make all the data and all the migration maps come alive.

Perhaps we can correct our near-sightedness with compassion and see a more spectacular world.

ENDNOTE: By popular demand: below is a recording of the forum mentioned by Ellingsen that included panel moderator Wilkinson of Yellowstonian exploring the impact of sprawl on wildlife, open space and rural communities. The group of experts featured at the event co-hosted by Gallatin Valley Earth Day were Eric Ruark of Numbers USA which produced a recent analysis of the effects of sprawl on wildlife in Greater Yellowstone, Deb Davidson of the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, Chet Work of the Gallatin Valley Land Trust, former Teton County, Idaho Board of Commissioners Chair Cindy Riegel, and professional planner Randy Carpenter who is executive director of Friends of Park County in Montana.

What sets Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies apart in the Lower 48 and most of the world? We still have large wild mammals able to move across landscapes because their routes have not yet been fragmented by development that makes them impassable. Roads are part of the challenge, but as the Center for Large Landscape Conservation says, wildlife overpasses and underpasses are no panacea, and their promise diminished if communities and their elected officials are not protected habitat on both sides of a highway. This image appears in The Atlas of Yellowstone, 2nd edition, a book we encourage our readers adding to their shelf.