EDITOR’S NOTE: This is part of an ongoing series, Wild Journeys, inspired by Helen Seay’s multi-species outdoor wildlife mural in downtown Jackson, Wyoming that was commissioned by Wyoming Untrapped.

by Todd Wilkinson

The town of Jackson, Wyoming and its engulfing dell known as Jackson Hole is named after a 19th century mountain man few modern people have ever heard of—Davey Jackson. But, if the enclave were instead given an identify tied to a totemic wild animal, it would be, more fittingly, “Elk Valley.”

The trappings of elk iconography in Jackson Hole are everywhere, from the famous archways made of interwoven elk antlers in downtown Jackson to the presence of the National Elk Refuge; from the names of businesses to the official logo of the National Museum of Wildlife Art—the only fine art museum devoted to wildlife subject matter that’s officially recognized by the US Congress.

In local homes you can find elk heads and antlers displayed as hunter’s trophies on the walls and folksy elk antler chandeliers hanging over long banquet tables; in the vibrant art gallery scene, you’ll encounter paintings, sculptures and photographs galore of wapiti; and, yes, you can see elk represented today in Helen Seay’s marvelous two-walled, multi-species mural. (To learn more about that, click here, or you can find it—and sit still in the presence of her imagery—on the backside of Hatch Taqueria & Tequilas at 120 West Broadway).

Adding to their cultural mystique, elk have been foundational to the outfitting, guiding and hunting economy of not just Jackson Hole but throughout the Rockies, and, of course, they’re beloved by millions of wildlife watchers. Historically, the indigenous Crow Nation (Apsáalooke or “children of the large-beaked bird”) called what is today the Yellowstone River that begins just south of Yellowstone National Park and flows 700 miles toward its confluence with the Missouri, “Elk River.”

Just as that river flows, so, too, do herds of wapiti (the name the Shawnee in the eastern US gave to elk which speaks of their traditional geographic distribution and how native peoples associated place names and their own identities with wildlife).

Second only to moose, elk are the largest members of the cervid (deer) family in North America, weighing between 500 and 1000 pounds. Although they have a similar appearance, analysis of mitochondrial DNA indicates that Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus canadenis) is a species distinct from European red deer. (C. elaphus)

In case you didn’t know this, the plural reference for elk is elk, not elks, though there’s a venerable social organization in the US known as the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks.

So, here’s the fantastic, uplifting news: today, there are more elk in the Lower 48 and western Canada than there were 150 years ago. The current population estimate is around one million. Such is an astounding achievement in wildlife conservation, though it belies a deeper truth. Prior to Europeans pouring into the interior West from the East and Southwest, scientists estimate there were 10 million elk ranging from the Pacific Coast to the dells of Appalachia and everywhere between. Then their abundance and distribution winnowed, as was the fate of so many species, due to killing by settlers and commercial market hunters, habitat changes and loss caused by landscape fragmentation. Seay’s mural gives us reason to reflect on what happened in the past and extrapolate what some of the forces, above, might mean for wildlife in the years’ ahead.

Think of “Elk Valley” as being a nexus for a pulsing biological power grid that converts sunlight into caloric energy which is then dispersed over a vast area. Fueling biodiversity, this system is constantly recycling in a true re-generative way.

Nothing signals the shifting seasons in the Rockies more than the sounds of “bugling” bull elk that commences in late August in the high country and then plays out across the floors of valleys from Arizona to the Canadian province of Alberta in September and October. Along with wolf howls and loon-song on northern lakes, it represents a true call of the wild.

In Jackson Hole and other corners of Greater Yellowstone, the spectacle is backdropped by the brilliant yellow and orange hues of aspen and cottonwood leaves. Bugling is a magnificent expression of courtship behavior with bulls pursuing cow elk during the mating season, or “rut;” it’s punctuated by the brassy-sounding vocalizations of wapiti males trying to bring more females into their breeding groups while fending off rivals. And, it’s a true drama, potentially hazardous for human onlookers who unwisely venture too close and don’t give the animals space.

Adult elk can measure more than nine feet from nose to tail and stand five feet tall at the shoulder. Female elk do not breed until they’re nearly two years old and can then produce calves every year, but the quality of habitat—as measured in adequate nutritious forage—is an essential factor in successful pregnancies. Bulls and their mighty antlers get most of the attention, but mothers are the caretakers and teachers.

Elk also figure in the center of a functioning predator and prey ecosystem. During springtime, visitors to Grand Teton National Park can watch grizzly bear mothers teaching their cubs to hunt young elk calves at a place called Willow Flats. Researchers in Yellowstone confirm that bear on elk calf predation also happens there. While wolves have been portrayed as the chief predators of elk, which is true in winter when adult elk are more stressed and vulnerable in winter conditions, the most effective wildlife predator might be mountain lions which ambush their prey.

More consequential than the above, elk have special symbolic status for something else that modern Americans may not recognize. Did you know: they were among the biological touchstones that gave us the modern philosophy of conservation biology which recognizes not merely the wonder of diversity, but, like the interconnectivity of elk antlers in Jackson’s park archways, the interrelatedness of all native species in a functioning healthy terrestrial ecosystem. In the Lower 48 south of Canada, that concept is writ largest in Greater Yellowstone.

When the group, Wyoming Untrapped (WU), commissioned Seay to assemble a montage of Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife, it was with the intention that viewers not only embark on an art safari search to identify their favorite animals, but that they might learn something, realizing that species do not exist in isolation from one another. Lisa Robertson, co-founder of WU and WU board member Karen Hanson note that because Seay’s art speaks in a contemporary style, like that of street art, it is the hope that younger viewers drawn to it might gather at the mural with their elders and have a joint learning experience together, she notes.

Profoundly, elk were also the reason Jackson Hole became home to a clan of conservationists synonymous with the real beginnings of science-informed wildlife management, wildland conservation as we know it now and efforts to protect unmarred public lands considered the rare crème de-la-crème of unbroken terrain—federal “wilderness.”

In 1927, after studying caribou in the far north of Alaska for the US Biological Survey, a forerunner to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, biologist Olaus Murie was invited to relocate, undertaking a study of elk in Jackson Hole. He and his wife, Margaret E. “Mardy” Murie were joined by Olaus’s half brother, wildlife researcher Adolph Murie, who also would distinguish himself in ecology, and Ade’s wife and Mardy’s half sister, Louise, known as Weezy.

That humble foursome, who eventually settled, in 1945, at what is now the Murie Ranch near Moose in Grand Teton National Park, contributed indelibly to making Greater Yellowstone the cradle of American wildlife conservation.

Originally, Olaus Murie was tasked with trying to unravel a vexing problem: why were elk dying in Jackson Hole even when humans were giving them ample amounts of supplemental food in the form of hay? Less than two decades earlier, in 1912, the National Elk Refuge had been hastily created in Jackson Hole. Its primary purpose was giving elk supplemental rations to help them survive winter. The motive, while well intended, has set off negative consequences that continue to ripple to this day.

Murie’s years of ongoing study of elk behavior yielded a book in 1951, The Elk of North America, that is considered a classic. He and Mardy also co-authored a book, Wapiti Wilderness, that chronicles their family life in the field and is a must-read for people considering careers as field researchers.

Based on what he observed and documented, Olaus proposed five ideas that were controversial but are today considered the cornerstone of ecological thinking. First, he noted that healthy elk populations need plenty of secure habitat and healthy native foreage, and it’s a truism that applies to all species. Second, he noted how elk are critical pieces in a larger ecosystem puzzle; their presence affects and benefits other species. Third, and this is something also championed by his brother, Ade, carnivores (predators that eat prey species like elk, including wolves, bears, mountain lions and coyotes) are essential to having healthy ecosystems. Fourth, nature and wild places hold intrinsic value far beyond economic values ascribed to them by commercial markets. Fifth, elk and other ungulates in the Rockies move seasonally twice a year between the mountains and lower-elevation valleys and protecting those corridors is critically important—an insight that is the fulcrum of world-renowned research being carried out by the Wyoming Migration Initiative led by Dr. Matthew Kauffman, who credits the Muries with inspiring his work.

Olaus Murie faced resistance from colleagues in government when he courageously said healthy elk populations need five essential things: secure habitat and natural food; being treated as irreplaceable pieces in a larger ecosystem puzzle; carnivores which prey on big game animals shouldn’t be targeted with eradication; nature has an intrinsic value beyond its exploitable commercial worth; and species like elk need to be able to migrate as they’ve done for millennia

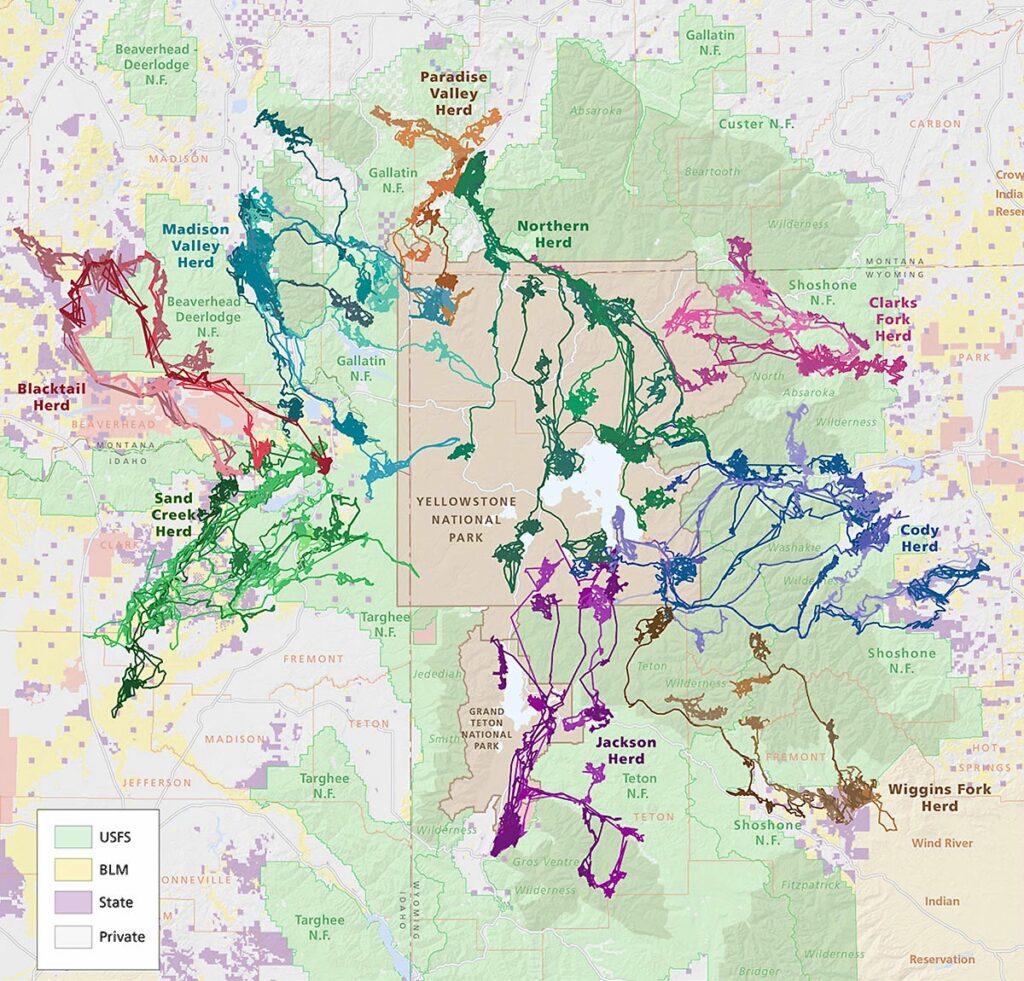

Murie serves as a crucial conduit between the thinking that resulted in creation of the National Elk Refuge and the Wyoming Migration Initiative’s cutting edge mapping using radio-collared animals to show movements of elk herds across vast sweeps of public and private land. When readers consider what’s at stake with migrations it’s impossible to forge the role citizens play in advocating for habitat protection and true science-based management.

In an essay about the Muries for the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Draper Museum of Natural History in Cody, Wyoming, Valerie Hamm wrote, “By 1937, Olaus had become a well-known and highly regarded naturalist—but he was also a disillusioned one. Tired of researching and writing reports that had little impact on the government’s policy toward habitat protection, Olaus accept a new position as director of the Wilderness Society. Soon he and Mardy were working with other key conservationists, including Howard Zahniser and Aldo Leopold, to promote environmental protection.”

Hamm then featured a passage penned by Mardy, “We had become immersed in the conservation battle and enthralled and stimulated by it and by the interesting people we met in connection with it, and we both knew that life was blooming, expanding, growing because of the new work Olaus had undertaken. It demanded a great deal of us both.”

Olaus is reverred, in hindsight, as “the grandfather of modern elk biology” and Mardy, at age 96 awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998 by President Bill Clinton, is held up as “the grandmother of the modern conservation movement.”

Elk had opened their eyes to understanding biological connectivity and how it courses through roadless wilderness lands. Olaus had commented on the importance, of saving habitat to the north in the Gallatin Mountain Range, home to the Gallatin Elk Herd and today a topic of debate over how much terrain managed by Custer Gallatin National Forest to protect as wilderness.

° ° ° °

What’s the outlook for elk? When Lewis & Clark were tasked by President Thomas Jefferson with mapping a route between St. Louis and the Pacific Ocean in the early 19th century, they traveled up in the Missouri River and its headwaters. Along the way, they encountered more elk on the prairie than in the mountains.

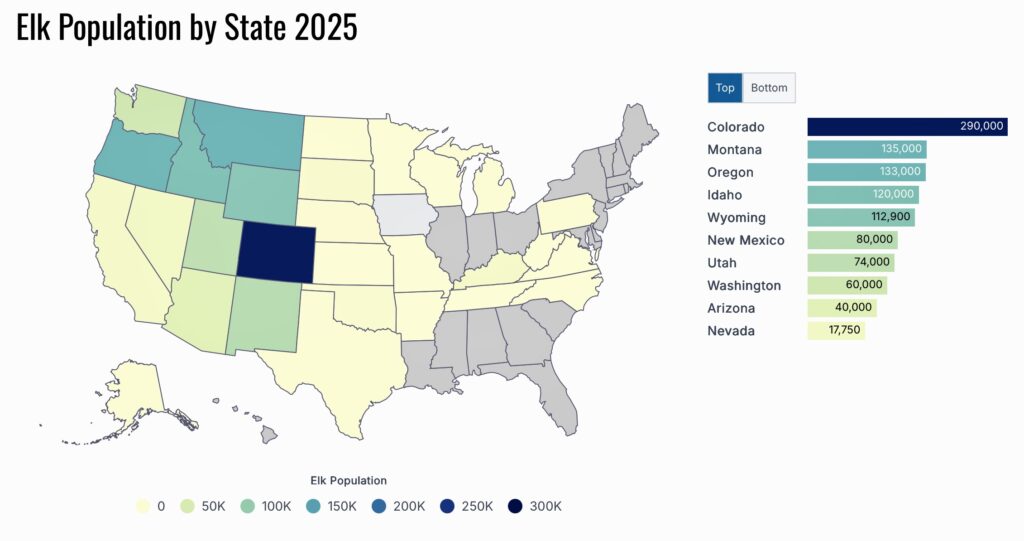

In these years of the 2020s there are around one million elk in North America—several times the number present a century ago. Many of the elk used in earlier species transplants were descended from elk survivors in Greater Yellowstone. That includes efforts to resuscitate dwindling herds in Colorado early in the 20th century and what’s telling about that is Colorado today has largest elk population of any state with an estimated 290,000 strong. Rounding out the rest of the top five are Montana with 135,000, Oregon with 133,000, Idaho with 120,000 and Wyoming with over 112,000.

In the wake of Lewis & Clark, and within the mere span of a century, the number of elk in the Lower 48 and Canada plummeted to perhaps 200,000. They were plundered by commercial market hunters providing meat and selling “elk ivory” teeth and taken by settlers to put food on the table. They were extirpated from Eastern states first, then on the plains and Upper Midwest, and finally they became rare west of the Mississippi.

What people forget is that one of the biggest predators of elk was, and is, not people nor native carnivores like wolves, bears and cougars—but habitat loss. Since 1984, the leading elk conservation group in the world, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, has secured the protection of 8.9 million acres of habitat mostly in the West, an area equal to four and a half Yellowstone Parks. Those efforts have benefitted hundreds of other species. RMEF has also been a leading collaborator with federal and state agencies in reintroducing elk to places where they were gone, such as areas of Appalachia. But the number of private land acres placed under conservation easement is not keeping pace with the volume being permanently degraded by development.

Essential to note is that in the Greater Yellowstone region, encompassing Wyoming, Montana and Idaho where wolves were reintroduced in 1995, elk numbers have risen in the last 30 years, hunter success has remained high, and some ranchers and farmers today complain of there being “too many elk” because they compete for grass with livestock, get into hay supplies and break fences.

Elk migrations have transformed the way we think about the importance of having landscapes free of sprawl. Migration routes allows us to grasp a larger superstructure of biological connectivity that illustrates Greater Yellowstone’s intactness which sets it apart. Many ungulate migrations are imperiled by rapidly-expanding development on private lands and a prime example is how habitat for the Gallatin Elk Herd in imperiled by expanding sprawl south of Bozeman, around Big Sky and in Paradise Valley.

Upwards of a dozen major herds and elk subherds converge upon the geographical center of the ecosystem—Yellowstone Park—from all directions. And then ,when the snow flies they leave the park for lower terrain, adhering to passageways that have served them for thousands of years. Noted ecologists Kauffman with the Wyoming Migration Initiative and noted researcher Arthur Middleton have likened the movement to the function of lungs whereby Yellowstone breathes in elk during the spring and then exhales them in late autumn.

That analogy goes deeper. Migrating elk and mule deer and pronghorn and many large species are like circuitry for transporting biomass—caloric energy—throughout the ecosystem. Their grazing positively effects soils and grasses which absorb energy from the sun. When the grasses are eaten they are converted to body mass in the ungulates whose migrations extend across thousands of square miles. Those ungulates in turn feed predators and scavengers and their decomposing carcasses nourish the soils, allowing the cycle to be repeated. Disrupt the migrations and it can become the equivalent of a blood clot in a major artery of the body. Not only does development sever the ability of animals to move, it halts the passing along of knowledge accrued by their matriarchs and generations before them, and it makes the energy transfer go haywire. Once its destroyed, it cannot be put back together again, especially if habitat is permanently lost.

What’s the value of having healthy circuitry? It’s incalculable though the marvel of a functioning ecosystem is priceless.

On a winter day in January or February a visitor to Jackson Hole can climb into a sleigh and enjoy a perimeter view of thousands of elk on the National Elk Refuge whose boundary begins at the northern edge of Jackson. Yet in many ways, that sight is an illusion of naturalness. Since the early years of the 20th century, the Elk Refuge was actually born as desperate attempt to stave off mass starvation of animals. That’s because elk habitat was being usurped by humans and wapiti became stranded in Jackson Hole during harsh winters, no longer able to migrate as they had done for millennia.

When migration corridors are destroyed or become constricted, it can affect the integrity of pathways hundreds of miles away. When species can’t move, they become resident animals where they are even more vulnerable to encroachment on limited habitat. This turns them into island population clusters and history shows that island populations decline faster than populations which can move. This is particularly important as climate change affects the availability of grasslands and water.

The gesture of providing alfalfa to the Jackson Elk Herd in winter has created not only yielded unnaturally higher numbers of elk, but biologists say it has created a dependency and inhibited their natural instinct to migrate to lower ground to avoid deep snows. Migration isn’t merely “an instinct;” it’s a behavior taught by mother elk to offspring, from one generation to the next. As teachers go away or have their instructions stifled, it is no different from destroying a human language tied to how people survive on a landscape. Across the last century, the state of Wyoming, in an effort to bolster elk numbers and keep wapiti from feeding on private property haystacks grown for domestic livestock, opened nearly two dozen other feedgrounds, operating in parallel with the National Elk Refuge.

Migration isn’t merely “an instinct;” it’s a behavior taught by mother elk to offspring, from one generation to the next. As teachers go away or have their instructions stifled, it is no different from destroying a human language tied to how people survive on a landscape

A graver concern today is that bunching up animals in close proximity makes them vulnerable to catching communicable diseases, such as Chronic Wasting Disease, brucellosis, tuberculosis, Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, hoof rot and other ailments, experts specializing in communicable epizoonotic diseases say. CWD is an always fatal malady that kills members of the deer family and has no known cure or preventative vaccine.

A recent analysis by researchers with USGS and collaborating agencies suggest that CWD stands to bring devastating population-level effects to elk numbers in decades to come, with more dire consequences happening faster if feeding at the Elk Refuge and state-run sites continue.

Still, closing the feeding operation has met with stiff resistance from outfitters and guides who say inflated elk numbers are crucial to their ability to profit by selling hunts. Wyoming also claims that discontinuing feeding would cause a collapse in elk numbers but that assertion is challenged by two facts: First, large numbers of wintering elk exist in Montana where there is no artificial feeding; and, second, CWD incidence is likely being accelerated by feeding but politics is trumping the cautionary wisdom of science.

° ° ° °

What’s at stake?

About 40,000 elk are estimated to roam through the three-state Greater Yellowstone region. That’s a lot of elk biomass which, in turns, supports a lot of biomass in other species.

Wildlife advocates, which include both senior US wildlife health experts and former senior biologists who worked at the Elk Refuge, say that those who resist closing the feedgrounds in Wyoming are selfishly putting their short-term interests ahead of the long-term health of elk, the ecosystem and the culture tied to elk. By knowingly allowing it to happen, some believe state officials are violating the sacred tenets of the public trust doctrine.

If CWD brings huge declines in elk as expected—and possibly to other members of the deer family that include moose and mule and white-tailed deer—what will be the negative cascade effect up and down the food chain in America’s most iconic wildlife ecosystem?

This brings us to a question that is increasingly on the minds of many, including hunters: why, against the wisdom of the Muries, do states continue to aggressively control carnivores? A growing body of scientific evidence shows that predators likely help slow the progression of CWD and other diseases because they remove sickened prey and likely help prevent maladies from spreading.

“Poisoning and trapping of so-called predators and killing rodents, and the related insecticide and herbicide programs, are evidences of human immaturity,” Olaus Murie remarked nearly a century ago. “The use of the term ‘vermin’ as applied to so many wild creatures is a thoughtless criticism of nature’s arrangement of producing varied life on this planet.”

Moreover, again, there is little evidence that wolves, cougars and bears are significantly harming larger big game populations. Just as feeding is putting elk in more peril, so too is the aggressive killing of predators antithetical to the cause of disease containment. Fully considering the important role of predators was recognized by Ade and Olaus Murie more than a century ago and it’s more prescient today than ever.

“The Muries were essentially the first to start laying the groundwork for a new way of thinking, connecting the human situation here with the needs of animals,” says Dr. Susan G. Clark, co-founder of the Jackson-based Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, a research outfit, and a longtime professor at Yale University. “They made the relationship clear and the responsibility we have to live conscientiously in this ecosystem if we want healthy wildlife. There’s been nothing like them since. The nearest has been the Craigheads with their work on grizzlies and other species. Fundamental is how the Muries tied the persistence of elk and other wildlife to the persistence of wilderness and the arguments they made, given the world we have now, are even wiser today. Their reasoning has withstood the test of time.”

As you gaze at the wapiti in Helen Seay’s mural, appreciate what the presence of moving elk means in America’s most iconic wildlife-rich ecosystem. And, if you hail from a distant city or suburbs, ask yourself: how and why is the caliber of wildness in your backyard different and what are you willing to do to help insure this American national natural treasure persists?

If you dwell in Greater Yellowstone, imagine the ecosystem without robust numbers of healthy elk herds. At the present rate, what was once unthinkable isn’t so much anymore.

ENDNOTE: This story is part of an ongoing series titled Wild Journeys inspired by Helen Seay’s two-wall outside mural in downtown Jackson, Wyoming and sponsored by Wyoming Untrapped. Other stories that have appeared so far: