by Todd Wilkinson

In June 2021, headlines appeared in Idaho newspapers declaring that, in a couple of fell swoops, predatory wildlife had killed 54 sheep on a farm in the Magic Valley near Twin Falls.

The reports echoed of a familiar narrative that might otherwise have indicted the usual suspects often maligned in the West—wolves, mountain lions, coyotes, grizzly and black bears.

Interviewing the affected grower of domestic sheep, journalist Hannah Welzbacker wrote that “in April, Rocky Matthews started finding dead lambs on his farm near Murtaugh Lake. At first, Matthews thought someone had killed the animals with a pellet gun. The animals all had puncture wounds the circumference of a No. 2 pencil.”

Livestock producer Matthews then did the math in his head and calculated that, if the killings continued at that rate, “in 45 days, I’ll be out of sheep.” He implied that some of the meat-eating culprits seemed to be attacking livestock purely for sport. Mr. Matthews estimated the value of his lost sheep then at $7500. By autumn of the same year, the toll grew to 60 sheep in what was described as a “snowball effect” with another 15 animals which, he said, “just disappeared.”

Reporter Welzbacker also interviewed a state wildlife official. She wrote, “Idaho Department of Fish and Game regional wildlife biologist Lyn Snoddy said [the predators] ‘strike from above and use their [claws] to grab the animals. In this process, they can sever internal arteries and wait for the animal to bleed out.’”

Graphic descriptions, indeed. Similar predations were happening in other parts of the county. At the venerable news outlet, Tractor Supply Magazine, writer Jennen Bell Hoffman noted how the attackers’ sharp tools “can slice through hide in seconds.” And, alluding to their pack-like hunting techniques, and how they hold quietly in the trees until the opportunity is right, the reporter added, “They wait and observe. It’s a matter of seconds before dinner is served….This is not the opening scene of a horror movie, but instead the reality faced by many farmers and ranchers across the country.’”

To make sure readers understood the severity of the menace, the predatory wildlife allegedly sowing terror was referenced as “ferocious and stealthy hunters, costing hundreds of thousands of dollars in livestock and poultry losses annually [across the US].”

As another indication of this, across the Idaho border near Albany, Oregon on the other side of the Cascade Range, a different family running sheep and goats estimated that their operation loses 300 lambs a year to the same predators, costing $37,500. Click on this youtube link and fast-forward to the three-minute, 15-second mark to hear a rancher discuss a bald eagle allegedly posing a threat to a cattle calf.

Regarding these attacks and the other that opened this story, there was no major public outcry or ruckus. No claims that these predators represent a dire existential threat to the livestock industry or other wildlife populations; no calls to initiate bounty programs, or enlist sport hunters and trappers to control the vile vermin and knock down their numbers to “manageable levels;” no demands for aerial gunners to arrive; no debates as to whether it should be ethical (as in Wyoming with wolves) to run down the offending animals with snowmobiles; no adding these predators to the lists of critters featured in hunting contests where prizes are awarded to those who kill the biggest and most animals; nor was there any rhetorical grandstanding in Congress to legislatively remove them from federal protection as a way to validate states’ rights, freedoms, liberties and while also creating memorable hunting experiences enjoyed by families.

Why do some states claim federal protections applying to grizzlies, wolves or wolverines are expressions of overreach by the federal government but not when it concerns bald eagles?

Had the livestock losses above involved wolves, grizzlies or mountain lions, there surely would have been fury expressed by agrarians. But the malefactors were, in fact…. bald eagles….America’s national wildlife symbol.

Why does this matter, besides the sensation that you, as a reader, might feel being left dumbstruck with irony?

In addition to the obvious hypocrisy pertaining to the way some meat-eating wildlife in the West are subjectively villainized, with state laws tailored to aggressively control their numbers using lethal means, the management status of bald eagles makes for provocative comparison. It may, in fact, provide a way forward in the debate over proposed delisting of grizzly bears in both the Greater Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide ecosystems of the Northern Rockies.

The main arguments often invoked by politicians, ranchers and hunters in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho for removing grizzlies from federal protection are that: 1. Numeric thresholds pertaining to biological recovery of the species have been reached; 2. That states will allegedly do a better job of managing bears than the federal government; 3. That the cost of recovery has imposed an onerous financial burden on states and halted natural resource extraction; 4. That one of the primary objectives of recovery is to allow trophy hunting of a recovered species again and give citizens enjoyment that has been denied them; 5. That hunting would be a significant revenue generator for state coffers; 6. That hunting of “conflict animals” would be a great, effective management tool.

Science and the reading of the Endangered Species Act actually debunks several of those assertions. Grizzly bears in Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide ecosystems have been listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act since 1975. Ironically, even things the Fish and Wildlife Service declared in its 1975 press release have been debunked by science-based facts that have emerged over the last half century. For a short time after sport hunting of bears was banned in Greater Yellowstone, grizzlies could still be hunted in northwest Montana and killing of bears, even as numbers dwindled, was allowed in defense of human life and livestock protection on public lands—the latter being one of the very reasons why that species and others were decimated.

Reduced to inhabiting around two percent of their original home range that existed in the West in 1800, and subsequently extirpated from all but four states, bears were dying at rates that far exceeded their reproduction.

Primary causes of death were killing done in the name of private livestock protection even on public lands, trophy hunting,poaching, real and alleged acts of self-defense, lethal removal of aggressive bears that had become conditioned to human food, and other causes. Another major earlier factor in the decline of bears a century ago had been widespread use of the deadly poison strychnine, spread across western open ranges and public lands to kill all wildlife carnivores through direct and secondly ingestion of baited carcasses because those native fauna were deemed a threat to cattle and sheep.

By comparison, bald eagles plummeted for many of the same reasons plus ingestion of lead ammunition by eating wounded game birds and scavenging big game carcasses. That’s a problem that still persists. Bald eagles first received special legal status with the Bald Eagle Protection Act in 1940. Then, in the decades which followed, prolific use of the lethal pesticide DDT to kill mosquitos caused numbers of eagles and other birds to tumble in steep declines as the toxic agent inhibited female birds’ ability to produce and hatch eggs—in addition to killing insects they feasted upon.

Bald eagles were given priority listing under what was called “the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966,” the forerunner to the Endangered Species Act (ESA), signed into law in 1973. Shortly afterward, President Richard M. Nixon said in a statement: “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed. It is a many-faceted treasure, of value to scholars, scientists, and nature lovers alike, and it forms a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans.”

Around the world, the ESA is widely viewed as the most consequential national wildlife protection law whose chief aim is recovering species populations in danger of disappearing. In 2007, amid much public fanfare and bi-partisan patriotic celebration, bald eagles were removed from ESA safeguards. However, the birds today still reman federally protected by both the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Should grizzlies—because they are even rarer in number, slower to reproduce than bald eagles and facing perpetual challenges through habitat loss on private lands in the Northern Rockies and climate change—also be the subject for new 21st century federal law that would protect them in perpetuity? From a conservation biology perspective, the idea is gaining traction.

But before we continue, consider this thought exercise: If the rationale is, as officials in the states of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho contend, that America recovers species so that they can be hunted again for personal thrill, to also covet them in death as decorative trophies and, in rare cases, to provide meat for the dinner table, then why don’t we sport hunt bald eagles?

But before we continue, consider this thought exercise: If the rationale is, as officials in the states of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho contend, that America recovers species so that they can be hunted again for personal thrill, to also covet them in death as decorative trophies and, in rare cases, to provide meat for the dinner table, then why don’t we sport hunt bald eagles?

Based on the argument that grizzlies ought to be hunted because they’ve surpassed minimum numeric recovery targets and are ranging more widely beyond the core of their original minimal recovery areas, consider what’s happened with bald eagles.

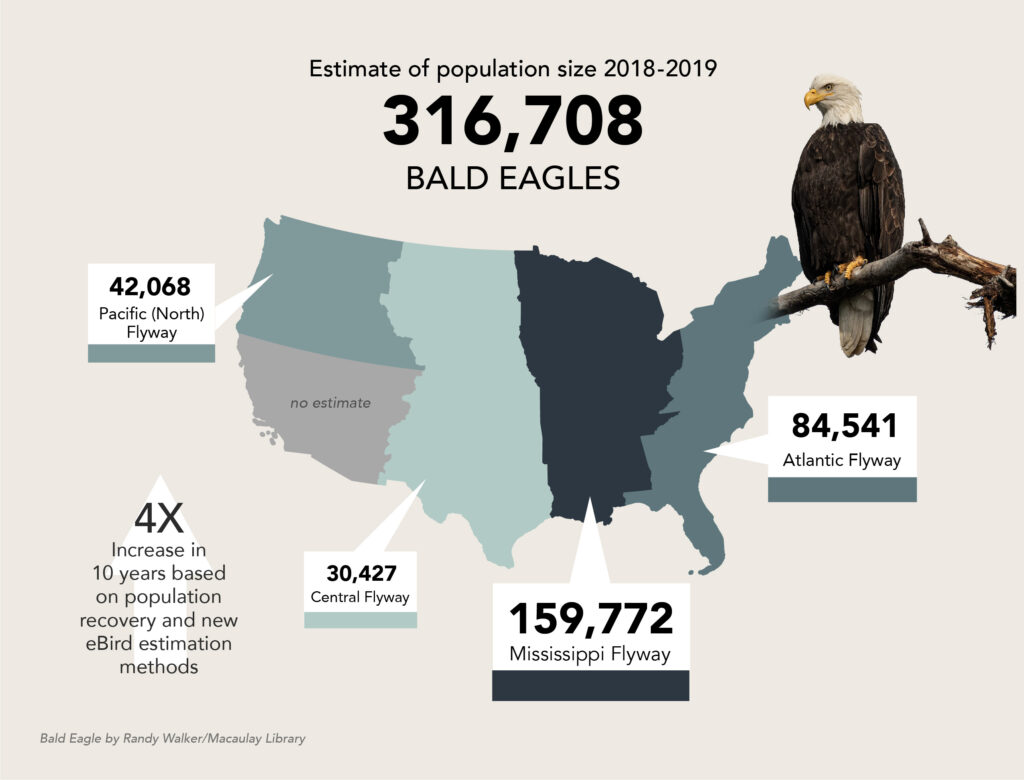

In 1963, there were just 417 known nesting pairs of bald eagles in the entire Lower 48. The white-crowned raptors previously had been killed as lethal nuisances to livestock, for their plumage and after World War II were decimated by DDT, which was banned in 1972. Today, according to the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s Migratory Bird Program, the bald eagle population was recently estimated at 316,700 individuals in the Lower 48, including 71,400 nesting pairs. The total population of eagles has quadrupled since 2009 alone, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service. The total number of bald eagles is nearly 1000 times larger and more widely distributed than when the species was listed in the mid 1960s.

The Greater Yellowstone grizzly population, estimated now to be more than 1000 individuals, may be between seven and nine times larger than when it spiraled toward its nadir of fewer than 140 bears in the 1970s and had only a few dozen females of breeding age.

Today, there are around 2000 grizzlies in all of the Lower 48. Not long ago, the lead scientist with the Yellowstone Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team noted that in the core of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the number of bears is no longer growing and rapidly proliferating sprawl is filling up many mountain valleys that previously were thought to be secure habitat areas beyond public lands. What this means is that as humans permanently fill in these space, there will be less land available for bears to maneuver; it includes the potential loss of safe, critical travel corridors that exist between tracts of public lands.

For comparison, the population of bald eagles in the Lower 48 is 157 times greater than grizzlies. Although eagles are relatively slow to reproduce, grizzlies have a dramatically slower reproduction rate. Solely for the sake of argument, if it’s justified for grizzlies, why not have sport hunting seasons for bald eagles?

For comparison, the population of bald eagles in the Lower 48 is 157 times greater than grizzlies. In the big picture, bald and golden eagles do not exact a large negative impact on livestock—compared to other causes of death—but it’s a greater toll than grizzlies and geographically speaking they affect far more ranchers and farmers.

Note: Yellowstonian is certainly not suggesting that bald eagles be sport hunted, but rather examining the pretenses for why grizzly bears, given the push to delist, must necessarily then be sport hunted.

Using the same arguments being invoked by the states for grizzlies, hunting eagles could generate jobs and income for outfitters, guides and taxidermists who could turn them into trophies perfect for display on the walls of homes and offices. It could help reduce predation on cattle and sheep and give hunters unforgettable chances to “harvest” “surplus” and birds labeled as “conflict eagles.” Similar to grizzlies, which most hunters do not eat, the states could offer tasty recipes for how to roast eagles just as the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and Wyoming Wildlife Federation did for bears. Given their high profile and the prestige of drawing an eagle tag, some lucky households could surprise guests at their Thanksgiving day feasts by swapping out turkey for eagle and serving it on the holiday banquet table.

Further, it’s been a long time since hunters have been deprived of being able to sit in a blind and bait or call in eagles. Haven’t they waited and suffered long enough?

Snark aside, these are exactly the same kinds of justifications made for delisting grizzlies and recommencing a sport hunt. Why do people wince at killing one species for fun but not another?

In addition, there is an economic argument that western members of Congress would likely invoke if the topic were bears or wolves, not eagles. The US Department of Agriculture, in a published 2015 survey of ranchers and farmers, reported that bald and golden eagles killed 6,680 cattle calves nationwide, representing about 2.8 percent of total predation on calves caused by wildlife. For comparison’s sake, domestic dogs killed 15,740 calves, representing 6.6 of total losses; mountain lions allegedly killed 11,500 or about 4.8 percent; wolves allegedly killed 8110 or about 3.4 percent; and bears (mostly black) allegedly killed 1,810 calves or about 0.8 percent. Coyotes were blamed for allegedly killing 126,810 calves, accounting for 53.1 percent of losses attributed to predators. (Millions of livestock were lost to other causes, including disease and other illness, foul weather, and injury).

Between 2015 and 2020, according to the USDA, Montana wool growers lost between 700 and 1200 sheep annually to eagles (bald and golden). Eagles also ate trout stocked in private ponds. The tally for livestock allegedly lost to eagles in 2020 was more than twice the number—500— lost to grizzly and black bears; three times the number of losses attributed to wolves; and 200 more than were blamed on mountain lions. The losses attributed to bears, wolves and mountain lions often are cited by ranchers and those in the predator control business as reasons for their lethal removal and having hunting seasons.

The amount of economic loss allegedly owed to eagle predation in Montana in 2020 was $216,000. By comparison, the estimated cost attributed to bears was $104,000; $82,000 for wolves and $64,000 for mountain lions. In Wyoming, in 2020, the deaths of 3,100 sheep and lambs were blamed on eagles, and in 2021 the number of livestock allegedly lost to eagles rose to 4,000, compared to both species of bears (grizzlies and black) blamed for 400 livestock losses, wolves 300, and mountain lions 800.

In the big picture, bald and golden eagles do not exact a large negative impact on livestock—compared to other causes of death—but it’s a greater toll than grizzlies and geographically speaking they affect far more ranchers and farmers.

Fact: nature tourism dollars generated in part due to grizzly bear watching opportunities in the areas around Yellowstone, Grand Teton and Glacier national parks alone far exceed, in a single year, what the states of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, combined, have spent on grizzly bear management in half a century.

Again, Yellowstonian is not endorsing this notion, but using the logic advanced by politicians in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, think of the revenue-generating possibilities that could, ostensibly, be realized by selling bald eagle tags. Since a huge percentage of eagles migrate, like waterfowl, there could be a spring and autumn season. In 2022, the Wyoming office of the Bureau of Land Management announced that citizen volunteers had counted 576 eagles—376 bald and 153 goldens—on a single day along 1500 miles of highway in the Powder River Basin alone. The tally was the highest recorded since 2006 when the counting began and that’s just a small portion of the state.

In 2018, when Wyoming was about to launch its first sport hunt of grizzlies in 44 years, it planned to issue 22 bear tags.

States could push to have bald eagles de-classified as a trophy animal and probably a lot more hunting tags than those for grizzlies could be issued and sold. Or, they could, the same as they have done for wolves in 85 percent of the state, officially categorize them as vermin predators allowing for them to be killed 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, by almost any means. Remember, there are more livestock allegedly killed by bald and golden eagles in Wyoming, according to official statistics, than are attributed to wolves.

Eagles could be stalked using baits just hunters do with black bears; night-vision infra-red goggles could be employed as they are for wolves. And imagine the sporting fun that could be had if one could pursue eagles using drones?

To appease trappers, the raptors could also be trapped with steel legholds or snares and then, after dispatching, have their feathers sold to make money, just like furs are. (Note: at present only Native Americans can legally kill and possess bald and golden eagle parts in order to use for religious ceremony, but the practice is federally regulated).

Certainly, some in-state and out of state sportspersons would probably jump at the opportunity to demonstrate their love of country and hunting by having their eagles transformed into flying poses by taxidermists, and hung on game room walls, just as waterfowl are.

Think of the boasting rights it would bring to successful hunters who successful draw tags in an eagle lottery and the priceless stories of adventure that could be told. The governors could contribute a few bald eagle tags every year that could be auctioned by hunting organizations and sold for tens of thousands of dollars to raise revenue for conservation.

Videos of how hunters braved inclement weather and rugged terrain to take their 14-pound female eagle with eight-foot wingspan could be shared on youtube as they are for hunted big game animals and vermin. Moms, dad and kids could take selfies of themselves posed with the bald eagle they just felled and proudly post those images on social media, and, if they are so inclined, circulate the pictures in part to taunt the tree-huggers likely to decry eagle hunting as barbaric.

A final argument states could melodramatically assert for bringing back a bald eagle hunt, the same as they do for wolves and grizzlies, is protection of public safety (especially children) and pets. If you read comments posted on the internet or testimony delivered by state and federal lawmakers from Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, claims are routinely made about the imminent threats lobos and bruins allegedly pose to kids, dogs and cats. If you take those lawmakers at their word, their hardy rural constituents live in constant fear and terror. Theoretically, those lawmakers could also contend that bald eagles have the potential to swoop down and nab babies out of the arms of unsuspecting mothers as well as scooping up small dogs, puppies and kittens—just like flying monkeys nabbed Dorothy and Toto in The Wizard of Oz. Apparently, eagles have attacked people, but such incidents have been extremely rare. To prevent such tragic incidents, fear-mongering politicians from the West could declare that rural people must be allowed to pre-emptively kill eagles flying over their ranches.

Yes, obviously, most of the above is presented here in gest but it should raise serious questions about our motivations as a society when making the same ridiculous assertions about other animals.

For all of the reasons being offered for why grizzlies, wolves and mountain lions should be hunted, why not bald eagles? Along the same lines of inquiry, why not hunt wild horses, burros, peregrine falcons, whales and manatees? Why aren’t there rancher-sponsored sport hunts of cattle and sheep. Indeed, many people reading this will likely find such scenarios to be appalling and heretical, but they are based on subjective biases, not any compelling scientific reason.

When a species is federally protected, as grizzlies and bald eagles have been, all Americans are stakeholders. When an animal is delisted, it then becomes the jurisdictional domain of the state where it resides and is managed on behalf of citizens in that state by the state fish and game agency. Unless it remains federally protected, even when surprising metrics of so-called “recovery,” as bald eagles do.

The truth is there’s no hard and fast rule that says animals rescued via the Endangered Species Act must necessarily be hunted. It’s an option some states decide to exercise as a reflection of prevailing values. Why society—and politically appointed state fish and game commissioners— choose to allow hunting of certain species over another is purely arbitrary, political and sometimes specious; it’s not based on any compelling biological or monetary rationale as demonstrated above.

Anthropomorphically (which is to say assigning human values to animals), bald eagles have been turned into symbols. Mated pairs are together for life and we attach virtues to them such as courage, strength, valor, beauty, honor, intelligence and loyalty—traits which could also easily be ascribed to grizzlies. Who would doubt Jackson Hole Grizzly 399’s faithfulness to her 18 cubs, her family values in raising them, and her intelligence in being able to non-aggressively navigate throngs of humans?

As for the economics, nature tourism dollars generated in part due to grizzly bear watching opportunities in the areas around Yellowstone, Grand Teton and Glacier national parks alone far exceed, in a single year, what the states of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, combined, have spent on grizzly bear management in half a century.

Another truth is that in the federal public land West, where there are millions of acres of habitat being stewarded for public wildlife species managed by the states, all American taxpayers, not just residents of local states, fund federal agencies that play a critical role in the survival of wildlife. The investment in land stewardship dwarfs what states spend.

So, how can the populations of Greater Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem grizzlies be removed from ESA status and still be protected?

° ° ° °

On the back of a napkin at Ted’s Montana Grill restaurant in Bozeman, Montana, I was taking notes not long ago as Robert Keiter advanced a hypothetical notion. Keiter explained a way out of the current socio-cultural-biological quagmire that involves grizzly bears in Greater Yellowstone and politicians aggressively pushing to legislatively delist them. They cites the reasons mentioned above.

Keiter is not a person who engages in advancing whimsical flight-of-fancy ideas. He is the Wallace Stegner Professor of Law at the University of Utah Law School. He is an expert on federal environmental laws and earlier in his career he wrote a book, The Wyoming Constitution, that is considered the definitive overview of codes in the Equality State. He also has written several overviews on the evolution of conservation thinking in the Greater Yellowstone region and we saw each other again at the recent 16th Biennial Scientific Conference held in Big Sky where he was the keynote speaker.

Proponents of delisting say that recovery criteria have been met and therefore bears should be removed from federal protection. The integrity of the law is at stake, politicians assert, and “bears need to be managed” through a limited “harvest.”

Grizzly advocates, who have prevailed twice in getting delisting attempts reversed in court, don’t want it to happen because one of the states’ prime motivations, they argue, is restoring sport hunting. Among those championing this view and confirming their worry is Montana Governor Greg Gianforte who enthusiastically wants to restore sport hunting. Notoriously, Gianforte, who identifies as a big game hunter, attracted national ridicule when he shot and killed a wolf that wandered out of Yellowstone National Park and was caught in a leghold trap. The lobo was kept alive—its leg in the trap— till he could kill it. Later, Gianforte also shot and killed a mountain lion, that was part of ongoing cat research, after it, too, left the protective confines of Yellowstone and was treed by hounds—kept there until the governor could arrive to shoot it. In both instances, he was criticized for engaging in activities involving dubious levels of what is known in the hunting world as “fair chase.” One can’t help but wonder: if it were legal, would Gianforte hunt a bald eagle?

Grizzly advocates claim that, contrary to assertions made by Gianforte, bears already are being managed—in fact quite well through joint federal and state collaboration that sometimes involves translocating or lethally removing bears, but it works. Had it not been a success, there wouldn’t be any discussion about delisting.

Keiter proposes a third way forward as response to the current polemic and it’s one in which both sides could claim victory. It’s an alternative that intrigues Dr. Christopher Servheen, who for 35 years led American grizzly bear recovery in the West for the Fish and Wildlife Service. Notably, Servheen wrote the nation’s Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan and supported delisting, but today he stands in opposition saying that states have adopted aggressive policies that could easily be interpreted as “anti-bear” and would undermine ongoing long-term recovery. Read his testimony that he delivered on Capitol Hill before the House Natural Resources Committee in 2023 and noted, “Unfortunately, many people think that delisting only requires reaching a certain number of animals as required by the species Recovery Plan, but that is incorrect.”

Servheen, a longtime hunter, angler, professor at the University of Montana and current board chair of the Montana Wildlife Federation, also has noted that hunting grizzlies does not represent an effective way to manage bears. As an aside, but pertaining to one of the arguments made by states for delisting, Servheen says there is paltry evidence to support the contention that ESA protection for grizzlies have imposed serious economic hardship on states (compared to the benefits of recovery) or prevented resource extraction on public lands or development on private lands from going forward.

Next year will be the 50th year since grizzlies in the Northern Rockies were given protection under the ESA after state efforts to keep bears alive were clearly failing. Bringing back grizzlies from the brink is not an easy task—in fact it has been the hardest in the history of the law—but the last half century is proof that the ESA had done its job with one of the most fearsome animals on Earth, Servheen says.

However, biologically speaking, in the face of many different factors including a record influx of people coming to the region, there will never be a time when a permanent banner is erected that proclaims “Mission Accomplished.” Grizzly bear recovery and maintaining a biologically-viable population in the years ahead, he says, hinges not on getting hunting quotas right. Foremost, it will require protecting adequate habitat to support a viable population. That means preserving habitat that is still secure which includes keeping large ranchlands undeveloped and economically viable using incentives, reducing the causes of human conflict that include not building subdivisions in certain areas, elevating human understanding, awareness and tolerance of bears, and having good laws and penalties in place to dissuade poachers. Similar thinking exists with how bald eagles, delisted from the ESA, remain protected under two other federal laws.

“Unfortunately, many people think that delisting only requires reaching a certain number of animals as required by the species Recovery Plan, but that is incorrect.”

—Dr. Christopher Servheen, author of the US government’s Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan and who supported delisting but now stands in opposition based on concerns that sound science-based management objectives have been usurped by politics and backward cultural thinking.

The Endangered Species Act has done its job in reviving the prospects of grizzlies in the Northern Rockies and that’s a group achievement worth celebrating, Servheen and Keiter say. But that is only part of the picture. It does not mean bear recovery going forward will need any less vigilance, investment and forward-minded management that, incidentally, also benefits the prospects of survival for hundreds of other wildlife species.

“What if the federal government removed the Greater Yellowstone grizzly population from its ESA protection but, just prior to doing that, Congress placed bears under the jurisdiction of a new federal law? You could call it the American Grizzly Bear Protection Act,” Keiter says.

The grizzly might be one of those species, like the bald eagle, that needs to remain legally protected forever. “It could be argued,” Keiter said, “that grizzlies will face even more threats as we go forward into the future than bald eagles which are more highly adaptive and inhabit a much wider range.”

Those who want bears delisted because they claim the ESA has done its job and management should be partially given back to the states can claim victory, and so, too, do people who believe bears need ongoing protection given the growing amount of pressures they face, especially the human footprint of sprawl that is negatively and permanently affecting habitat on private and adjacent public land.

As climate change alters habitat, wildlife will need to roam ever farther to find adequate food and water to sustain its numbers. If the Northern Rockies are going to retain their vaunted status as unparalleled concentrations of rare wildlife, and as the landscape becomes flooded with swelling numbers of human visitors and permanent residents, animals having more access to terrain still unfragmented by human structures, roads, and busy recreation trails will be critical, scientists say.

Passage of a law like the American Grizzly Bear Protection Act would be a reflection of how societal values have changed in the 21st century, validating the fact that grizzlies hold special mystique, they are a symbol of the country’s dedication to world-leading wildlife conservation, and even that their economic value far outweighs the costs of perpetuating their survival. He believes it would also establish the states of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho to be beacons showing how protection of nature focused on co-existence is a far more bullish proposition than the natural resource extraction boom and bust cycles of old that were not only unsustainable economically and ecologically, but they resulted in destabilized communities.

The presence of grizzlies give those states distinction, and make them stand out, as places able to do what no other states have the courage and habitat left to accomplish. Even California, which often boasts of its superiority and abundance of high-tech wizards, cannot ever bring back grizzlies, which were once more numerous in that state than any other and are a remnant emblem on its state flag.

Why do we, as a nation, invest in rescuing species from the brink of extinction? Why do we put so much effort into preventing wild animals from disappearing from a given region? Why do we reintroduce native species that were depopulated or exterminated, and what kind of second chance are we giving them?

Why do some states claim federal protections applying to grizzlies, wolves or wolverines are expressions of overreach by the federal government but not when it concerns bald eagles? Can politicians urgently pushing for grizzly delisting articulate what biological recovery means in light of irrefutable factors that represent a formidable counterweight to it persisting?

Arguably, we ought to know and understand why we approach those questions differently for bald eagles than we do for grizzly bears. If we don’t know why, what does that say about us, and our ability to allegedly think rationally when the arguments we invoke don’t seem to make sense?