by Todd Wilkinson

A few days ago in mid-July, Evan Stout was bracing himself and his community for inevitable sad news. A Yellowstone grizzly bear was going to die. He knew it, but there was nothing that could be done to prevent it.

Since early June when the large male bear, known to researchers as Grizzly 769, toppled the first garbage can in Gardiner, Montana, filling his belly with tasty trash and even leaving paw prints on the flaps of a few lids, Stout knew the animal was headed down a tragic, inexorable path toward its own doom. He just hoped the final catalyst couldn’t involve a close injurious encounter with a human.

It wasn’t the grizzly’s first romp through the streets of this small historic national park border town located literally on Yellowstone’s northern edge. Gardiner is the place where President Theodore Roosevelt arrived by train in 1903. Today, there’s a namesake stone archway commemorating his visit. It’s possible Grizzly 769—weighing more than 500 pounds and whose age was 15—passed through the arch in route to crossing the local high school football field where it was recently observed. Fittingly, Gardiner High School’s class mascot is “the bruins”

For the most part, the bear’s circumnavigation of Gardiner had been stealthy, Stout says, except in years’ past when 769 wandered into someone’s backyard north of town and shook apple trees, helping himself to the ripened falling fruit in late summer.

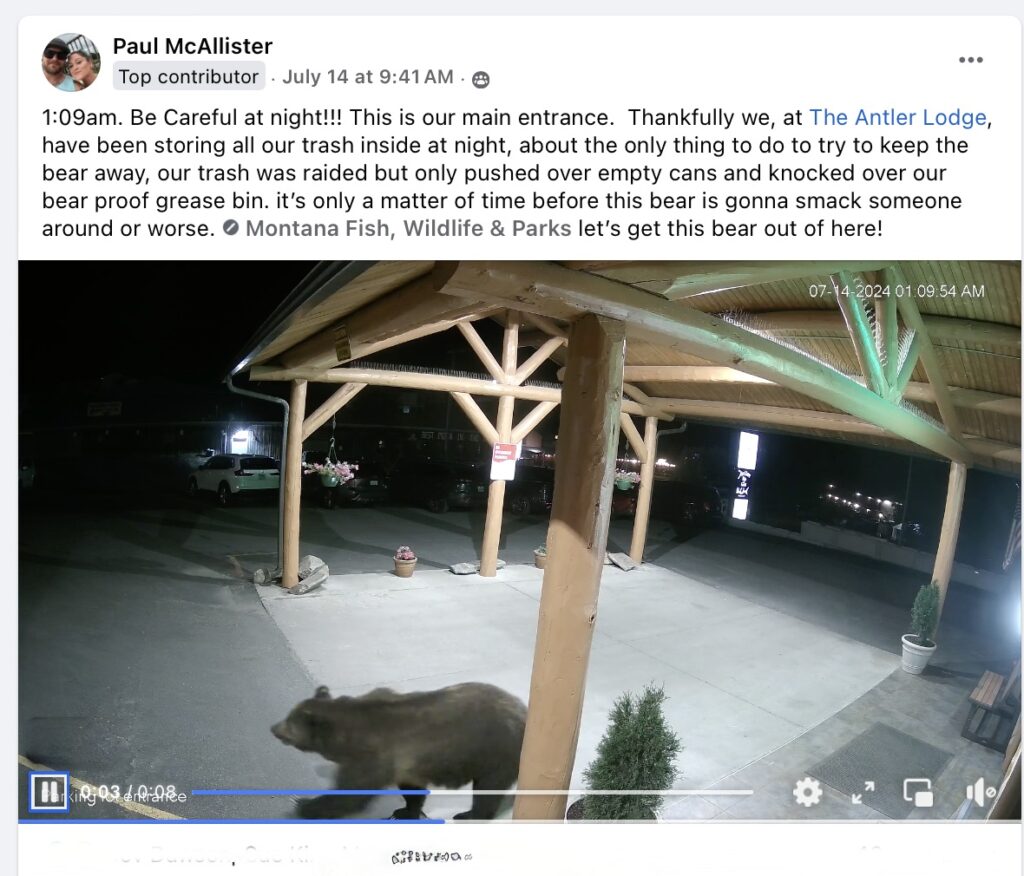

This year, the grizzly showed up early and left scattered trash piles in his wake. He continuously evaded capture in baited barrel traps installed around town. Combined, his ongoing nocturnal raids of trash cans and restaurant dumpsters, him trying to break into employee housing on the outskirts of Gardiner and attempting to enter a housing unit in Mammoth Hot Springs—Yellowstone’s official headquarters—in July, left social media abuzz. He possessed mystique and also, notoriety.

Empathy and outrage poured out on his behalf, but there was corresponding fear. Justifiably so, says Stout, who by day leads visitors on wildlife watching excursions into the park through his business, Yellowstone Wildlife Guide Company. On his time off, as a volunteer, he has joined other citizens in doing all they can to prevent grizzlies and black bears from gaining access to a wide range of human-related foods whose aromas waft for miles, far beyond the boundary of America’s most famous nature preserve.

The initiative Stout helps to lead is called Bear Awareness Gardiner launched by a local non-profit conservation organization called the Bear Creek Council which itself is an affiliate of the Northern Plains Resource Council. The campaign seeks to trade out as many traditional garbage bins as possible for bear-proof trash containers. Despite its valiant efforts, the transition has been slowed due to limitations of financial resources and, in some cases stubborn resistance. In the meantime, bears getting addicted to human foods remains a chronic problem. And it’s most sorrowful when mother bears and cubs must be removed.

Bear Awareness Gardiner is doing important work filling a vacancy created by the absence of government. Gardiner is unincorporated and doesn’t have a city council. It falls under the jurisdiction of Park County which is dealing with a number of growth-related issues and there hasn’t been the political will to implement regulations mandating bear-proof garbage containers.

As part of Bear Awareness Gardiner’s program, all residents in the Gardiner Basin are eligible to receive one 64-gallon bear-proof trash can for free for their residence. Businesses (including short-term rentals) are eligible to cost-share the expanse of a can for 50 percent of its wholesale purchase. Besides providing bear-proof trash cans, the initiative has an electric fencing loan-out program that residents and businesses can deploy around apiaries (bee and honey-making boxes), apple trees or chicken coops. In 2023, a team of 20 volunteers also helped to pick apples from trees at local residences and get them removed from the landscape as bears move into autumn hyperphagia when they are incessantly hungry trying to put on weight prior to hibernation.

So, what’s the big deal about lethally removing a single grizzly, one might ask?

In isolation, if grizzly recovery were merely a numbers game, and given that there may be 1,000 grizzlies today in the Greater Yellowstone population, the incident might be casually dismissed as insignificant. To bear experts, however, it’s what the saga of the Gardiner bear represents as a foreboding of things to come that matters. The issue is not one of somehow training bears to do what people want, but the much more vexing challenge of changing human behavior so that bears aren’t lured to their own demise.

“For the last 150 years since Yellowstone was created, we as humans have been allowed to behave in certain ways as bears receded from the landscape and so as the population recovers, and if we want to prevent conflicts, many of which are avoidable, we need to adapt our thinking,” Stout says.

In the last decade alone, a half dozen grizzlies between Gardiner-Jardine and Yankee Jim Canyon have been killed by wildlife managers because somewhere they ran into unnatural food and their cravings led them to become aggressive. That tally doesn’t include the destruction of a mother and two cubs that were also eliminated.

When “people food” and “pet foods” are available to wild bears it’s like a human taking fentanyl or heroin and getting instantly hooked. Bears will switch to eating trash, rather than subsisting on natural staples if given the choice and such edibles are convenient. There is no treatment program that grizzlies and black bears can be sent away to for deprogramming. The rate of recidivism—as in grizzlies successfully overcoming their addiction—is far less than a human addict. That’s not because bears are dumb or weak willed; quite the opposite.

Just as odors wafting from garbage do not adhere to artificial lines created by cartographers, neither do wildlife. The latter are drawn to the former, and the scent-detecting capabilities of grizzly bears are legendary. Exhaust vents piping fumes from sizzling steaks and bison burgers in local Gardiner eateries and backyards catches the attention of people, fueling their hunger pangs, and, so, too, of bears.

The forward lines of the problem are not the city limits. They are actually outlying areas at the far peripheries of towns and counties where new tendrils of sprawl are becoming points of first contact for bears, Stout says. “If they get a food reward out there, it incentivizes them to keep wandering in closer, deeper into populated areas, especially if along the way their curiosity keeps getting reinforced.” Gardiner, he says, is a microcosm but because it is the gateway to Yellowstone, it ought to be setting an example. The huge invasion of newcomers to Greater Yellowstone from urban areas or states where wildlife isn’t present in recent years exposes new variables in pondering grizzly recovery which treats private land issues as a major blind spot, experts say.

On Friday, July 19, Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks sent out a press release announcing that the Gardiner grizzly had been shot and killed in the vicinity of Maiden Basin Road north of town. Immediately, there was sadness expressed by local residents.

I had spoken to Stout just a few days earlier. “The state has culvert traps set up around town. They’ve been trying to catch him for a month. He is a really wise bear when it comes to staying away from traps and he’s been finding plenty of unsecured food in dumpsters.” Stout paused, then added, “He the intelligence of a young human, the problem-solving skills of a teenager [in opening trash containers and breaking into structures] and the strength of 10 men. Grizzlies are incredibly smart animals with amazing memories. They go back to the places where they receive rewards.”

The number of close run-ins with people was growing. Stout predicted the end of the bear was imminent because there were no other options. He couldn’t be captured and released because his craving of trash was past the point of no return. Nor could he be sent off to a zoo because they’re no long taking bears.

“One thing I’m hearing is that people are upset with state and federal agencies working together to remove this bear. People want to have someone to blame,” he explained. “I do this work I do because I love bears and if you ask residents of Gardiner, most will say the same thing. Ironically, it’s because we want bears to be on the landscape that makes it necessary to remove this grizzly. The worst thing in the world is if a bear hurts someone. Then social tolerance, which has been hard earned, goes down.” There is a larger issue of grizzly bear conservation in play, he added, “but the immediate topic is one of protecting public safety and thinking about how to prevent this from happening again.”

“Ironically, it’s because we want bears to be on the landscape that makes it necessary to remove this grizzly. The worst thing in the world is if a bear hurts someone. Then social tolerance, which has been hard earned, goes down.”

—Evan Stout with Bear Awareness Gardiner

Fran van Manen, leader of the USGS’s Yellowstone Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, told Brett French, reporter for The Billings Gazette, that Grizzly 769 had been previously been captured by researchers several times, fitted with ear tags and at one point with a radio collar. The bear moved widely throughout northern areas of Yellowstone but it could no longer be tracked after its collar fell off in June 2023. Grizzly 769 returned to Gardiner this spring.

On Wednesday, July 17, wildlife officials from different state and federal agencies were summoned to try to find the bear. Then, early Thursday morning, the grizzly had broken into a home off Maiden Basin Road of town and the owner notified authorities after firing warning shots at it with his pistol. The animal was shot by game wardens as it attempted to flee across the Yellowstone River and subsequent investigation confirmed it was the bear in question. The animal floated down river. (It’s head and claw-bearing paws were subsequently severed from the carcass by wildlife officials because a previous incident showed thatt human scavengers will try to take the parts to keep as souvenirs or sell).

A few weeks prior, I had reached out to Kerry Gunther, Yellowstone’s chief of grizzly research, who lives on the outskirts of Gardiner and, for decades, has been an important scientific voice in bear recovery. He’s emphasized on several occasions how vital it is for communities and counties surrounding Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks to reduce bear food attractants—for the benefit of bears and people.

Of the Gardiner grizzly, he mentioned an added wrinkle involving the lack of affordable housing for service workers in the tourism industry. “I think what’s happening is a good story to tell,” he said. “Seasonal workers in Gardiner can’t find housing and so they live in their cars or in tents. You can imagine food storage is not great at those locations, and a few of the incidents occurred at those sites.”

In 2014, Gunther and six colleagues involved with bear management published a scientific paper documenting that grizzlies eat at least 266 different kinds of natural foods—among them 175 different plant species, 37 invertebrates, 34 mammals, seven fungi, seven bird, four fish, one amphibian and one algae species plus a certain kind of soil (yes, dirt!). The problem is that human food can become an overriding temptation, especially in years when weather conditions make natural staples at certain times of the year more difficult to come by.

Gunther’s point is that food addiction problems with bears are being caused by lax trash storage practices pertaining to local residents and businesses,—and by visitors and seasonal workers who also are being less than fastidious with how they cook, store food and take care of leftovers. After announcing the Gardiner griz had been shot and killed, the state in its news release noted it had accessed food stored in coolers, vehicles, camp trailers, sheds, and garbage cans that were not bear resistant or unlocked bear-resistant garbage cans. Hence, the mission of Bear Awareness Gardiner is essential.

What Stout hopes now is that the bear’s story can highlighted to show it did not die in vain. He stands on the front lines of a proliferating challenge but also a diffuse one. Almost every single Greater Yellowstone resident and the millions of visitors who come here each year own a piece of a problem often treated as an afterthought. Yet the factors which led to the lethal removal of the male bear points to a huge obstacle to ongoing grizzly bear recovery, says Dr. Christopher Servheen, a resident of Missoula, Montana, who for 35 years oversaw grizzly conservation in the Lower 48 for the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Before learning more from Dr. Servheen, there’s something simple that bear advocates, who care about the fate of transboundary Yellowstone grizzlies, can do right now: support the Bear Creek Council’s Bear Awareness Gardiner initiative and help advance the community’s transition to 100 percent compliance. Bear Creek Council is participating in the Park County Community Foundation’s annual Give-a-Hoot-Fundraising drive until the end of July and every dollar you give on behalf of Bear Safe Gardiner will help keep bears alive. In fact, given the summer drought we’re in there’s a strong chance that bears are dealing with decreases in availability of natural foods and more may be showing up on the outskirts of towns.

“My biggest concern now that the nuisance bear has been removed is that Gardiner residents and businesses go on as usual and let their guard down. It was business as usual got us into this mess, and resulted in the death of the animal,” Stout said. “The removal of one bear does not mean our problems are over and solved. We still have a long way to go to be considered a bear safe community. Bear Awareness Gardiner will continue to help with that effort, but it requires buy-in from our locals to get there.”

The Bigger Picture

Bears getting into garbage cans have become a chronic problem not only around Gardiner. It’s happening in the Gallatin mountains south of Bozeman, especially with black bears in the vicinity of a place appropriately named Bear Canyon. Inattentive trash disposal has been an ongoing concern in Big Sky where a number of grizzlies in recent years have become addicted to human foods and then had to be lethally removed. In Paradise Valley, young grizzlies got into trash at an unsecured dump in 2021 and 2022 and a mother with a cub was killed by wildlife officials. Conflicts have happened in the Madison Valley of Montana, Island Park, Idaho, the outskirts of West Yellowstone, Tetonia, the Hoback, and the West and South Forks of the Shoshone River near Cody.

The death of a bear can begin with something as simple as an employee at a resort failing to close the door of a trash impoundment, which is what happened, state wildlife officials say, in a recent instance at Big Sky. It can involve humans having a barbecue and leaving uneaten bites of meat on the patio table, or not taking a dog foot dish in at night, or building a home next to a national forest and planting an apple tree.

And, on top of it, then there can be a devil-may-care behavior of tourists coming to Greater Yellowstone on vacation. When things like these are extrapolated across the bioregion, day by day, year by year, it creates a mine field for grizzlies to have to navigate and, without humans taking the issue seriously, Servheen says, there are going to be a lot more dead bears and potentially dangerous encounters between bears and people and their pets. Bears should not be made out to be menaces or liabilities, he notes, because human behavior is getting them into “trouble.” So who are the “trouble makers”?

“Grizzlies don’t go looking for trouble with people. They want to avoid humans if at all possible. Two things are happening out there,” says Servheen, who today is retired from government service and serves as president of the Montana Wildlife Federation. “First, they are being lured into our towns and suburbs by food and, second, we’re moving into places where bears are or into landscapes that used to be rural and now are undergoing transition from ranches, farms and natural tracts to development. That’s not good for wildlife”

“Grizzlies don’t go looking for trouble with people. Two things are happening out there. First, they are being lured into our towns and suburbs by food and, second, we’re moving into places where bears are, or into landscapes that used to be rural and now are undergoing transition from ranches, farms and natural tracts to development. That’s not good for wildlife.”

Dr. Chris Servheen, former national head of grizzly recovery for the US

Bear proof cans, like wildlife overpasses and underpasses, are no panacea when pondering the impacts of thoughtless, wildlife-unfriendly development occurring at a faster pace in rural landscapes. It’ sprawl that is putting humans on a collision course with bears and other species, he says.

The most important factor in grizzly survival is safeguarding high quality bear habitat. (Note to those developers of multi-million dollar homes and resorts in Big Sky, Jackson Hole, the Shields Valley and other locales in Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies: You do not win green bonus points for virtuous conduct by lavishly striving to make your structures LEED Platinum certified. You’re not helping to save the planet nor are you doing nature a favor. It’s of no positive benefit for a grizzly bear mother with cubs or any other wildlife species whose secure habitat is being usurped by a human footprint that will leave them permanently extirpated from that piece of ground. Plus, a LEED-certified home that has an unsecured trash can or leaves out dog food on the veranda or has a bird feeder spewing seeds is just as problematic as a seasonal worker having to live in their car and storing food in their portable cooler).

People building LEED Platinum trophy homes in wild country are neither saving the planet nor doing grizzlies any favor. A LEED certified home that has an unsecured trash can or leaves out dog food on the veranda or has a bird feeder spewing seeds is just as problematic as a seasonal worker having to live in their car and storing food in their portable cooler.

The Gardiner griz was not a famous bear, like so many are in Jackson Hole. Over the course of roughly six weeks this year, he had become somewhat infamous, active mostly at night. He did not have a human-bestowed nickname. Although his movements were elusive, he was caught on security and citizen-installed trail cams and occasionally spotted by eyewitnesses engaging in various kinds of food seeking, indulge what had become a tenacious craving—call it an addiction or what wildlife officials call “conditioning”—to non-natural foods discarded or left out by humans.

The “problem,” and Servheen wouldn’t call it that, is that grizzlies are incredibly opportunistic because they need to be to survive in the wild, using their keen sense of smell to guide them to sustenance wherever it is found. They can gain a whiff of something edible from miles away, and if it’s people sloppily disposing of their trash, or leaving odorous foods unattended (including hunter’s and their game animals in the fall), or a restaurant even failing to secure the grease bins where cooking oil used to make deep-fried menu items, it begins a process that cannot be reversed.

Whether by accident, unconscious thinking or a tourist trying to be cut and tossing a half-eaten muffin toward a bear along the roadside, the consequences can be lethal. The tourist in the tour bus might be miles away headed toward the next destination, but that fed bear can become a dead bear.

Servheen says it’s worth reminding people that the problem of food-conditioned bears at dumps in Yellowstone was a major contributing factor to grizzlies nearly disappearing from the park and necessitating federal protection under the Endangered Species Act. For the first six decades of the 20th century, generations of grizzlies gathered around dumps, teaching that learned behavior to their young. It led to widespread “begging bears” along roadsides, making incursions into developed areas and campgrounds, voraciously seeking “food rewards” associated with people.

Bears were aggressive, people got injured, bears were killed. After the dumps were shut down in the 1970s, 80 to 90 grizzlies were killed each other to protect public safety and property and remove bruins that couldn’t shift back to seeking out only natural foods. Yellowstone’s grizzlies, which represented the bulk of the ecosystem population, crashed. At only point there were only 23 females of reproductive age left and each year only a few handfuls were producing cubs. Conditions were dire and it’s why a major part of the original recovery plan—which continues today—focuses on food sanitation issues.

What some politicians in the three Northern Rockies states that have grizzlies don’t seem to realize, Servheen says, is that grizzly recovery in modern times has no terminus; it is an ongoing challenge and an opportunity, but in order to keep a healthy population of bears on landscapes becoming increasing cluttered with human development on private and growing numbers of recreationists using public lands beyond Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, food storage needs to become a higher priority in towns and counties within the sphere of bear country. What is he talking about geographically?

It’s an area that extends from southern reaches of Greater Yellowstone in the Wind River, Wyoming and Salt mountain ranges northward to the US border with Canada, particularly since a major goal of recovery—and one that has hampered attempts to delist the species—to connecting Greater Yellowstone bears with those in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem. Priority areas are those towns and counties in close proximity to the parks, especially those undergoing huge surges in human population and development pushing right up the edge of public lands. Among some of those counties: Park, Gallatin, Madison, Sweetwater and Carbon in Montana; Teton, Park, Sublette, Freemont, Hot Springs and Lincoln counties in Wyoming; and Teton, Fremont, Madison, Bonneville and Caribou counties in Idaho.

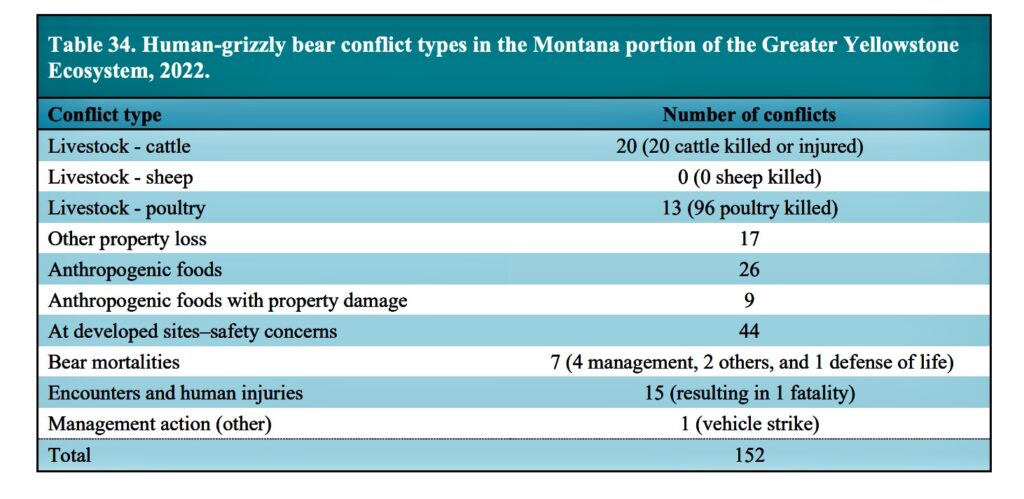

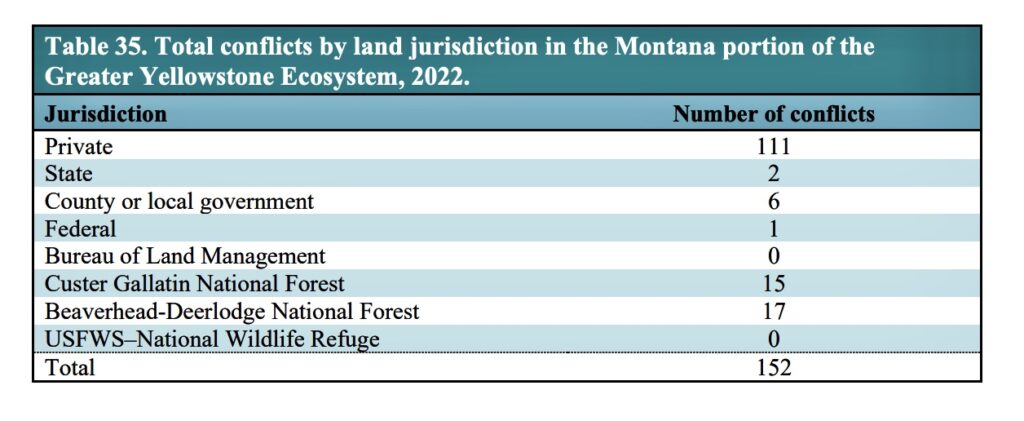

The absence of private lands figuring much in the calculus of grizzly recovery is considered by many to be not only a major flaw of the Endangered Species Act but in ignoring the trendiness of habitat loss and how sprawl will continue to drive up conflicts. It also casts shade on the optimistic portrayals of recovery made by politicians. Two graphs, below, created by the Yellowstone Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team for its annual 2023 report, illustrate the point. It highlights stats from 2022 which show that anthropogenic food issues, associated conflicts and safety issues at developed sites account for a large percentage of incidents in the Montana portion of Greater Yellowstone. The next graph shows that more than two-thirds of the conflicts in Montana occurred on private land and they did not involve livestock predation. It means that a much bigger onus for perpetuating grizzly recovery relies not just on federal land managers but decisions by elected officials at the county and local level in various forms of land use planning and enacting regulations that prevent conflict.

“Bear recovery is more of a secure habitat issue than a numbers issue because numbers of bears over time become a reflection of the quality of habitat bears are using,” Servheen told me. If bears are chronically being displaced and wandering into areas where they have a higher probability of dying, that does not bode well for sustaining a population, especially for a mammal that is as slow to reproduce as a grizzly.

To date, only Teton County in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in concert with the town of Jackson and other local government and non-government organizations has laid out an aggressive strategy, not to mandate the installation of bear-proof trash cans for every human resident and business but conveniently make them available for free or at reduced cost. Action was triggered by the harrowing long-distance meandering of famous Jackson Hole Grizzly and her four cubs in autumn 2021. In search of natural food, they wandered out of Grand Teton National Park southward through the town and suburbs south of Jackson where they came in contact with unnatural food attractants. It exposed how voluntary measures fail. Indeed, some residents even believe they are doing wildlife a favor when they feed animals, or lure them in to create photo opportunities. In early summer 2022, one of 399’s subadult cubs was caught and killed after it kept seeking human foods in a neighborhood of cabins near Cora, Wyoming.

Wyoming Game and Fish officials have said publicly that, in the future, should bears get delisted and management turned over to the state, they will allow trophy hunters to target so-called “problem bears” that get into trash and would otherwise be lethally removed by agencies. Many citizens in the region and beyond, who believe grizzlies should never again be hunted, say it could create an incentive for some people to deliberately do things that produce problem bears. And those deeply concerned about state management say Wyoming likely would have minimal penalties assessed against people dealing with grizzlies addicted to human foods and who then claimed they killed bruins in self-defense.

Servheen says that, as a professional bear manager, this is a major concern, for it exposes yet another of the serious wildlife management issues being heightened and made problematic by exurban development. It is happening throughout rural areas of Greater Yellowstone that only a few years ago would have been considered safe and appropriate areas for bears to re-inhabit and upon which the optimism of recovery was based. While federal agencies who oversee public land can compel national park, national forest and BLM managers to use bear-proof trash cans, that cannot happen with counties. Only by citizens applying pressure and elected commissioners who understand the gravity of the growing challenge will attitudes and regional culture change, he says.

Another thing worthy of note about Jackson Hole Grizzly 399. She is a poignant example of what a difference one single healthy mother bear can make. Over the course of her 28 years, 399 has given birth to 18 cubs and if one adds in the fact that cubs have been born of some of her grown cubs, she has at least 24 bears in her descending bloodline. She has given birth to one group of quadruplets, three sets of triplets, one litter of two cubs and three individual cubs.

Why more of Greater Yellowstone’s counties, located closer to the national parks and closer core of the ecosystem have not made bear-proof trash containers mandatory is unexplainable. County commissioners say they’ll get too much pushback from local citizens, or that costs are too high, or that they do not have the resources to enforce the regulations. In fact, the cost is nominal when extrapolated over the course of a few years, the move is considered a progressive measure to prevent injuries and conflicts and it’s a reminder that living and visiting Greater Yellowstone comes with added responsibility.

Stout and Servheen say voluntary compliance clearly doesn’t work as it only takes one business with a trash dumpster made of plywood to start a problem that can start with one bear and then extend to more. Plywood dumpsters, while they don’t work, are not illegal, Stout says.

In 1999, the Canadian tourist town of Canmore, Alberta, a gateway to Banff National Park, shifted to bear-proof containers and mandates compliance with violators given a fine. In that community, there’s also a social shame factor that gets aimed at abusers of the ordinance, with posts made on social media. Canmoreans have embraced better co-existence behavior as a cultural badge of honor.

This is the larger backdrop of the Gardiner grizzly whose death can be blamed on humans. While it was a state wildlife manager who pulled the trigger, the dealers who created the addict are people and it is a shared responsibility. “I keep telling people we need be creating an army of activists when it comes of these issues instead of always being re-activists,” Stout said. “All of this is about getting in front of issues which, in the long run, benefits wildlife and people.”

It’s also why, in the absence of Park County, Montana refraining from mandating the use of bear-proof containers, public support for entities like Bear Awareness Gardiner is so important. In fact, through the end of July, Bear Creek Council is one of the non-profits being featured in the Park County Community Foundation’s countywide Give-A-Hoot fundraising drive. Now is an ideal time to make a contribution as your money will directly be used to install more bear-proof trash containers and it very likely could save a grizzly’s life and/or prevent the injury of a human.

A Mainer by origin, Stout says that Greater Yellowstone being one of the rare places in the Lower 48 with wild grizzlies is one of the reasons he moved here. “There is an intrinsic value of what makes Greater Yellowstone different from Colorado. It’s true that Colorado is a beautiful state but the fact that grizzlies can still exist here is a huge piece of what sets the Northern Rockies apart. It’s important to me and the opportunity for clients to see bears and wolves is a vital aspect of my business and many other companies, ” Stout says. “If grizzlies and wolves and the diversity of species weren’t here, imagine how differently we’d be thinking about it? Whether we’re able to hold onto it is really up to us because it means that we have to think different.”