EDITOR’S NOTE: Among the three states whose borders converge to form the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Idaho’s contribution of terrain is often the most overlooked in the triumvirate. Yet the sweep of public and private lands that reside within the Gem State play a crucial role in the overall ecological health of many wildlife species in the region. Idaho’s portion of Greater Yellowstone extends from public lands southeast of Pocatello to northern portions of the Caribou-Targhee National Forest and Bureau of Land Management tracts stretching from the Centennial Valley to the outskirts of West Yellowstone, Montana.

Geographically, it represents a vital linkage zone for wildlife moving between Greater Yellowstone, the High Divide Ecosystem and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem along the US border with Canada. At present there are major growth issues related to sprawl and exurban development happening along US Highway 20 between Idaho Falls and extending north through Island Park to the shores of Henrys Lake. In the essay below, Rob Harding discusses the challenges of sprawl in Idaho statewide and the findings of a new report from NumbersUSA which is working on a study of sprawl in Greater Yellowstone, replete with a foreword from Yellowstonian co-founder Todd Wilkinson. —Gus O’Keefe

By Rob Harding

Idaho’s population has grown faster than any other state’s in the past decade. Since 1980, it has doubled, from 940,000 to over 1.9 million today, and this explosive growth is set to continue. By 2060, Idaho is on track to have a population of 2.7 million.

All that growth has consequences.

According to a new study of government data, Idaho lost more than 370,000 acres of farmland and natural habitat from 1982 to 2017. That means fewer pristine views, less habitat for wildlife, fewer farms for traditional livelihoods, and less peace and quiet.

Gem State residents don’t want more unchecked growth, according to new polling data. They worry that the droves of people arriving in recent years, particularly from California, will fundamentally change life in their hometowns.

Luckily, it’s not too late to stop the trend. If people want to “keep Idaho beautiful” and stop others from “Californicating” Idaho – as popular bumper stickers suggest – they can band together and demand common sense solutions from our federal, state, and local governments.

Idaho’s population has grown so much because America’s population did too. The country’s population went from 179 million in 1960 to 335 million today. Much of that growth happened thanks to immigration. In fact, annual legal immigration levels have tripled since 1960, to say nothing of illegal immigration, which is currently setting all-time records.

Many of these immigrants – roughly twenty-five percent per year – have gone to California. The Golden State’s population has ballooned to nearly 40 million.

No wonder, then, that Californians tired of crowded cities and high costs of living are fleeing for other states. No other state exports more people to Idaho than California.

Those new residents, whether in Boise or elsewhere, must live somewhere. So now Boise has become a rather large city, dotted with new neighborhoods and homes. The city ranked as America’s sixth “fastest-growing place” in 2023-2024, according to the US News & World Report. Meanwhile, Kootenai County’s population is on pace to grow by a whopping forty-two percent by 2040.

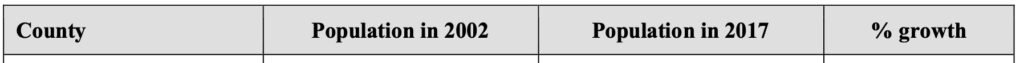

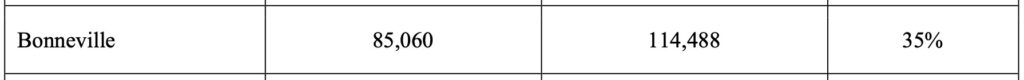

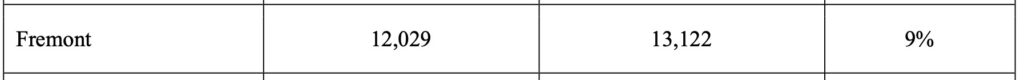

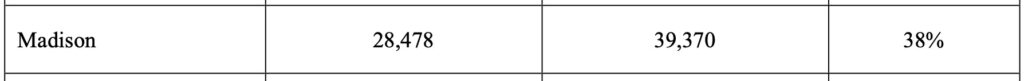

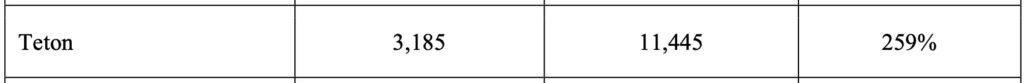

Idaho has four counties that reside squarely inside the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—Bonneville, Fremont, Madison and Teton. The population statistics, however, only tell part of the story. Missing is the number of vacation and second homes constructed in communities like Victor, Driggs, Tetonia, Island Park and Henry’s Lake. While residents may inhabit those properties all or, for many, only part of the year, their infrastructure of dwellings, outbuildings, driveways, yard lights and roads are set in place permanently. Along with them there are concerns about water quality related to groundwater pumping and the longterm viability of individual rural septic systems. In the case of Island Park, it is situated amid several noted trout streams that are tributaries to the Henrys Fork of the Snake River.

Whether people are present in those structures doesn’t matter; wildlife is still being displaced and increasing traffic loads are contributing to a rise in vehicle-wildlife collisions that pose a grave danger to both humans and animals. The Nature Conservancy recently rated the flats around Henrys Lake as possessing high habitat importance for biodiversity and the US Highway 20 corridor south of there similarly is a crossroads for a number of species, many of which are moving back and forth seasonally between Yellowstone National Park and winter range.

If the 370,000 acres of lost cropland and wildlife habitat in Idaho overall were concentrated in one area, that wouldn’t be great, but it would at least be manageable, keeping natural areas natural and built areas built.

But sprawl doesn’t work that way. New developments are often scattered across the landscape, causing habitat fragmentation by dividing up forests and rangeland. That’s terrible for wildlife, and the people who must deal with unwanted encounters, from bears raiding backyard pet food bowls to drivers who fear plowing into an elk on their commutes.

Sprawl also poses a threat to key industries. Idaho is famous for its potatoes, but fewer people know Idaho also leads the nation in alfalfa hay, peppermint, and barley production. We also excel in dairy products, sugar beets, and hops. Yet farmers have lost sixteen percent of their cropland in the last four decades. More sprawl often means fewer farm jobs.

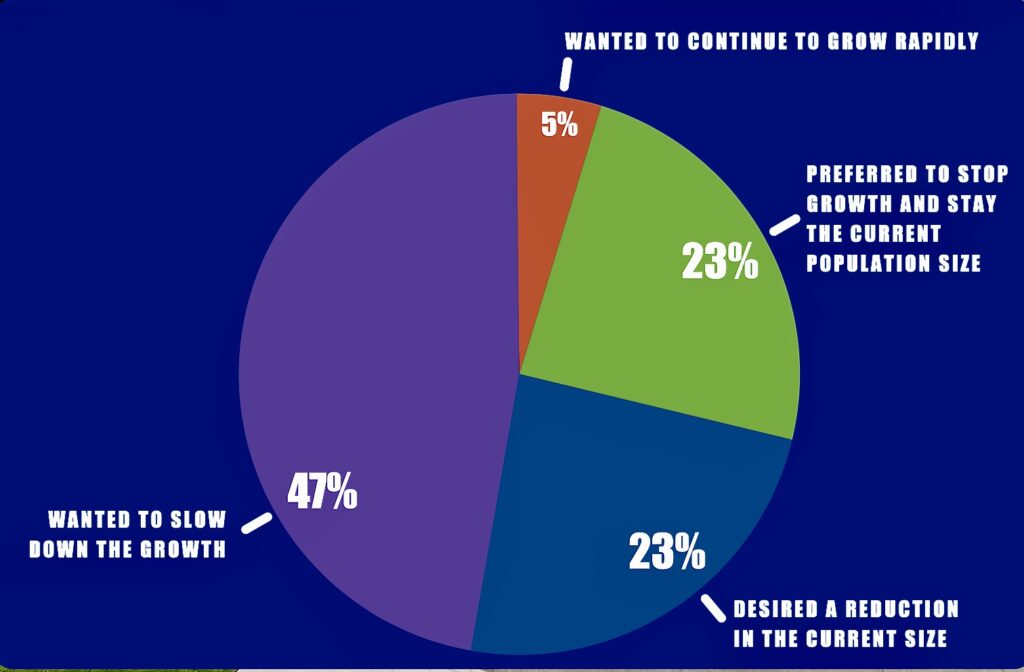

Idahoans don’t want to lose their natural beauty and traditional way of life to sprawl. In fact, 93 percent of Idaho voters want to either slow down, stop, or reverse population growth, while 77 percent think keeping current levels of growth will make the state worse, and 81 percent consider it “very important” to protect farmland from development to feed America.

Idahoans don’t want to lose their natural beauty and traditional way of life to sprawl. In fact, 93 percent of Idaho voters want to either slow down, stop, or reverse population growth, while 77 percent think keeping current levels of growth will make the state worse, and 81 percent consider it “very important” to protect farmland from development to feed America.

But to turn these wishes into reality, citizens will need to engage every level of government.

Start with federal immigration policy. Fewer immigrants to the United States as a whole, and California specifically, would ultimately mean fewer people moving to Idaho. We can demand that our congressional delegation support common sense immigration restrictions.

Second, local municipalities and counties can pass zoning laws that encourage new development to go up, not out. Instead of yet another subdivision, local towns and cities in our county, including Coeur d’Alene and Post Falls, can encourage multi-story and multi-family development along major throughways and town centers.

Finally, individuals can get involved with local organizations, both governmental and non-profit, committed to protecting natural places and farmland across the state. Interested people can contact their local soil and water conservation district, the Kootenai County Aquifer Protection board, or the county Farm Bureau, among others.

Idaho is beautiful. It’s why many have chosen to make it their home. But it won’t remain beautiful if unfettered migration and development continue.

EDITOR’S NOTE: What can be done, in the short term, to safeguard critical wildlife habitat and achieve landscape protection in a way that also keeps ranchers and farmers on the land in place of exurban sprawl? Here is a story written by Yellowstonian founder Todd Wilkinson for The Land Report magazine featuring the efforts of two ecologically-minded investors, Rebecca Patton and Tom Goodrich who worked with Beartooth Capital and The Nature Conservancy of Idaho to keep a vast sweep of land on eastern edge of Henrys Lake safeguarded. We find their efforts inspiring and believe you will, too. Lastly, what are the real consequences of sprawl? Read the Yellowstonian profile and interview with Lindsay Jones of Victor, Idaho about her work in wildlife rehabilitation and injuries to animals that is happening because of impacts brought by human development.

Stayin’ Alive: A Journey Of Healing: A Profile and Interview With Lindsay Jones