Introductory note from Yellowstonian co-founder Todd Wilkinson

History often turns on fickle twists of fate. What if Hitler hadn’t invaded Russia and ordered the German military to instead focus solely on conquering Britain? What if Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev hadn’t been rational actors during the Cuban missile crisis? What if George Armstrong Custer had not made a fatal, ego-driven miscalculation on June 25, 1876, ordering members of the Seventh Cavalry to ride with guns blazing into an encampment of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho along the Little Bighorn River in Montana?

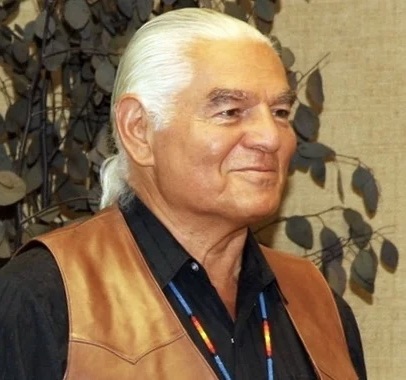

There are innumerable what ifs? What’s your favorite? The following piece is published in memory and honor of a dear departed friend, Ben Sherman (1939-2024), who passed away earlier this year. Ben was many things—a Lakota, an engineer who worked in the space industry, an expert in his tribe’s cosmology; and a visionary on the leading edge of advancing responsible indigenous tourism around the world. He pointed out the pricelessness and fragility of local cultures, and encouraged travelers not to trample all over them, exploiting them, to suit their own desires. Ben was also a board member of the First Peoples Fund, an indigenous arts organization founded by his niece, Lori Pourier which aids artists in cultivating a public presence; he is the uncle of Sean Sherman, the famous “Sioux Chef,” he was a member of a diverse and talented family. He was a father, brother, uncle and trusted friend to me, a gentle soul from whom I learned a lot and it changed the way I think about journalism. Ben also was a damned fine writer. The following essay was written by Ben to addresses a what if: what if his Lakota ancestors, upon meeting the Lewis & Clark Expedition as it moved up the Missouri River in 1804 had decided not to tolerate the Corps of Discovery’s imperious cultural insensitivities? How might that have altered the way Euro-Americans approached the West? How might things be different today in the absence of William Clark? For all of us, exploring these questions should invite deeper reflection, especially as we try to derive more than superficial meaning from the national holiday we call Independence Day.

By Ben Sherman

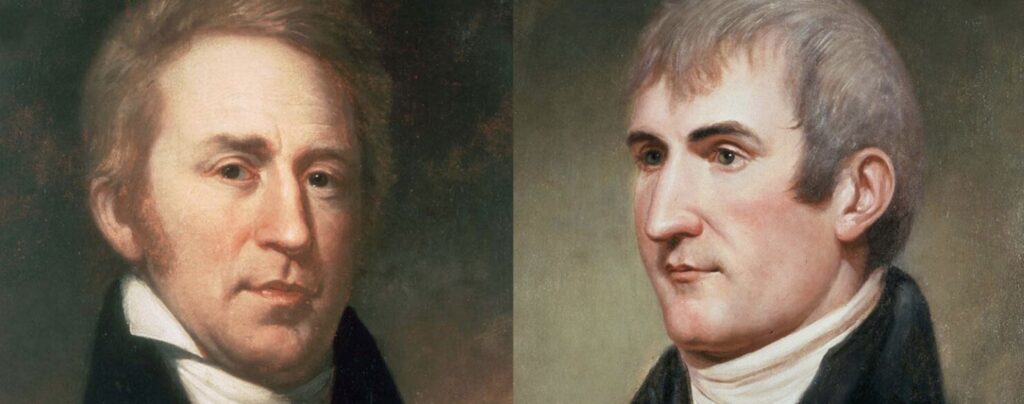

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark made their journey from St. Louis to the Pacific Coast and back, they observed a remarkable wealth of land, animals, plants and native cultures along the Missouri River and beyond to the ocean. It was essential to the success of the expedition that they find ways to get along well with the Indian tribes during the journey. They nearly succeeded.

Two of the most powerful tribal nations along their route, the Blackfeet and Sioux, were almost their undoing. In 1804, in what is now South Dakota, William Clark would have his first “bad” Indian experience. It happened in late September not far from where the Bad River enters the Missouri. Clark’s near-violent argument with western bands of the Sioux Nation would cause Lewis and Clark to describe them as the “vilest miscreants of the savage race.”

Clark was never known to modify the sentiment. The expedition was passing through the heart of Sioux country. They had been sufficiently forewarned of the potential hazards of traveling through the territory of the powerful Lakota. This encounter with the Lakota was the expedition’s narrowest escape with disaster.

What follows is not an attempt to engage in “cancel culture;” it is merely a suggestion that when we think about the West that is my home, and may be yours, that we consider the bigger, fuller picture.

When William Clark unsheathed his sword in a flush of anger against the Teton Sioux, he was prepared to do battle with a force that could easily have wiped out the small group of Americans. It so happens that the Sioux did not want to fight then. There was no good reason for risking Sioux lives to put these few invaders in their place. At that time, the Sioux did not hate or fear the white man.

But what they did fear was the white man’s strange and deadly diseases. When William shouted to the Lakota that he had “…medicine on board that would kill twenty such nations in one day,” the wise Lakota leader recalled the reports from distant tribes that had already been decimated by disease, and he decided not to take a risk with any “bad medicine” the interlopers might possess.

The encounter with the Lakota would be particularly unpleasant for William Clark. His journal descriptions were harsh, portraying the Lakota as “thin, small and generally ill-looking.” Two years later while drifting on the river through Lakota territory on the return trip, William Clark would make shouted threats to the Lakota again.

A Lakota warrior by the name of Makes the Song would have been about 18 years old at the time of the first encounter. It is remotely possible that Makes The Song was involved in the encounter with Lewis and Clark. But the likelihood is that he was further west, among the buffalo, where many of his people were. Makes the Song and the Lakota nation knew about the “wasichu” and most chose to stay away from these unpleasant, ungracious people.

Clark’s near-violent argument with western bands of the Sioux Nation would cause Lewis and Clark to describe them as the “vilest miscreants of the savage race.”

Seventy-three years later the famous grandson of Makes the Song would lead the last defiant band of Lakota into Fort Robinson, surrendering their guns and horses. The buffalo and other sources of food were almost wiped out in the Missouri region, and his people could not face another winter in a running fight with the US Army. Sitting Bull had fled to Canada. The rest of the Sioux people were confined to reservations, mere remnants of our homelands.

This grandson of Makes The Song was named Crazy Horse. The year was 1877.

Crazy Horse would die that year from a soldier’s bayonet blade placed in his back. The sacred Black Hills would be stolen from the Sioux in 1877. A Supreme Court justice saw fit to comment on the government’s conduct, “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealings will never, in all probability, be found in our history.”

A little more than a decade prior, John Bozeman, a Georgian who went AWOL in fighting for the Confederacy, headed West and blazed an illegal shortcut route between the Oregon Trail and gold discoveries around Virginia City, Montana. Ultimately, Bozeman and his trail, after whom the booming Montana city is named today, served as a catalyst for bloody clashes between western plains tribes and the US Army with its Crow and Shoshone allies, including the Battle of the Rosebud on June 17, 1876 which involved Crazy Horse and the Battle of the Little Bighorn eight days later.

The tendrils of the Corps of Discovery touched the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. It passed through the Missouri Headwaters area in 1804 and Clark and party members, prior to descending via the Yellowstone River and rendezvousing with Lewis at its confluence with the Missouri, trekked through the area of present-day Bozeman and the banks of Livingston. During the winter of 1807-1808, a member of the expedition, John Colter is believed to have been the first person of European descent to set foot in what would become Yellowstone National Park and he saw the Teton Range.

Ultimately, Bozeman and his trail, after whom the booming Montana city is named today, served as a catalyst for bloody clashes between western plains tribes and the US Army with its Crow and Shoshone allies, including the Battle of the Rosebud on June 17, 1876 which involved Crazy Horse and the Battle of the Little Bighorn eight days later.

Just seventy-three years after Lewis and Clark passed through the lands of the Sioux nation, the US Government would take most of the lands of the Louisiana Purchase from the Indians through a combination of deception, force, murder, starvation and broken treaties. Alcohol and disease would contribute. There were many “rank cases of dishonorable dealings” in the extremely rapid expansion of the United States into the new territory. One of the most egregious, that continued for decades, were indigenous children, ripped away from the comfort of their parents and families and sent away to notorious Indian boarding schools, some operated by the Catholic Church.

William Clark played a singular key role for the first 30 of those 73 years in launching the American takeover of lands, subjugation of Indians and expansion of America into the Upper Missouri region. Part of it was based on American expansionism rooted in The Doctrine of Discovery, conceived of by a Catholic pope that told Europeans in the 15th century basically that any lands not inhabited by Christians were there for the taking. In US history, it is referred to as manifest destiny.

Clark implemented new Indian policy as a powerful and influential political appointee under six different presidents, beginning with President Thomas Jefferson and continuing through the presidential administrations of James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren.

Clark’s extensive accomplishments can be viewed today as total and complete execution of Jefferson’s wishes. Jefferson had started his presidency with great optimism about civilizing and assimilating Indians into American society as yeoman farmers.

However, with each passing year his optimism waned. By the end of his second term, as he appointed the great expedition hero William Clark to the position of Indian superintendent for the new Missouri Territory, President Jefferson was devising a new policy for dealing with Indians.

Jefferson’s plan for the fate of Indians would be harsh and unremitting. Civilization and assimilation were replaced with removal or extermination.

Either way, through annihilation, forced removal or deception, Indian lands would be obtained for the growing American settler population. William Clark was being prepared to make that a reality. Clark spent several weeks in Washington DC before his appointment. He most likely had opportunities to learn firsthand of Jefferson’s policy for expanding America at the expense of indigenous people, some of whom he claimed to have befriended.

Jefferson’s Indian policy, according to Anthony F.C. Wallace’s Jefferson and the Indians, the Tragic Fate of the First Americans, would include predatory credit practices where the Indians would be allowed to accumulate higher and higher debts with traders and the U.S. government.

The government would then pressure the Indians to eliminate the debts through land cessions. The government would also stand by as white encroachment of Indian lands took place. Acts of atrocity committed on Indians defending their land, property and families, would follow, leading to Indian retaliation. Then the US military would invade Indian lands to protect whites and punish “hostile” Indians. Threats of a trade embargo or war, with parents worried their elders and children would starve, pressured the Indians into more treaties and land cessions.

The process was to be repeated over and over on the grandest scale that only a man of Jefferson’s capacity could imagine. Indeed, the seeds of ethnic cleansing and cultural genocide were planted by Jefferson. All that was needed was the persistence of resolute men to carry out his Indian policy, and he found one such man in William Clark.

I was born in 1939 not far from Wounded Knee on Pine Ridge in South Dakota where the infamous massacre of Lakota women and children happened in 1890, bringing an end to the so-called “Indian Wars.” Just 15 years earlier than my birthdate, Congress passed a law “giving” we Indians, who had been here 20 millennia, maybe longer, our citizenship as Americans but lacking, of course, was any sincere or honest extension of real constitutional rights.

Again, some have portrayed Clark (1770-1838) as an ally, a defender of Indian rights and benefactor of Sacajawea, the young Shoshone woman who helped guide the Corps of Discovery.

A few decades after he passed through the West with Lewis, he spent many years as governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Missouri region, a forerunner to the present-day Bureau of Indian Affairs. There, in St. Louis, he cultivated a reputation as a benevolent protector of the Indians, a defender of Indian law.

Some called Clark “the redheaded Chief.” He was even accepted by many Indian leaders—yet he was a man of power and reputation who demonstrated his friendship by taking millions of acres of Indian lands into the new American empire.

William Clark, his nephew Benjamin O’Fallon and his friend René-Auguste Chouteau, executed a combined total of 47 treaties with Indian tribes during the period 1815-1830. Clark ultimately had 65 Indian treaties executed under his watch.

William Clark personally participated in ten treaties that involved major land cessions from a number of tribes. The US would eventually violate every single Indian treaty. How did that square with US government’s sacred reverence for private property?

William Clark would succeed in clearing all Indians out of his home state of Missouri before he was done. Clark, his city of St. Louis and his state of Missouri, would reward those same Indian tribes that contributed to their wealth with a quick boot to their collective backsides.

William Clark was also an astute businessman from the very beginning of his long political career. He helped form the Missouri Fur Company along with members of the Chouteau family and Manuel Lisa. The Chouteaus were among the wealthiest families in St. Louis, as well as being William Clark’s business partners in Indian trade.

Clark and his nephews and in-laws, along with the Chouteaus, gained wealth from the fur trade, which decimated bever and other animals, and the general Indian trade. Government treaty money authorized by Governor-Commissioner-Superintendent Clark and paid to Indians found its way into company cash boxes in St. Louis. Government treaty goods provided to Indians were purchased from company stores in St. Louis. Alcohol was an important and permanent part of Indian trade, creating immense profits for the white traders.

William Clark had complete power over all aspects of the Indian trade, including the evil liquor that ruined many Indians and destroyed entire tribal communities.

Indeed, William Clark’s long reign as Governor of the Missouri Territory, Treaty Commissioner and Superintendent of Indian Affairs led to the eventual devastation of all free and independent tribal nations of the great Missouri region that he explored.

Not a single tribal nation, friendly or hostile, large or small, escaped the ravage.

William Clark’s long reign as Governor of the Missouri Territory, Treaty Commissioner and Superintendent of Indian Affairs led to the eventual devastation of all free and independent tribal nations of the great Missouri region that he explored. Not a single tribal nation, friendly or hostile, large or small, escaped the ravage.

Clark’s actions against Indians were not accidental but deliberate, well planned and sustained. It is as if he sought to inflict lifelong retribution upon the “vilest miscreants of the savage race.”

The direct link between the Indian removal policies of Thomas Jefferson and the Indian removal actions of William Clark is all too clear. Indeed, who can say that William Clark did not communicate with President Jefferson and plan the grand scale of scheming deceptions that eventually cost the Indians their lives, their independence and their lands?

William Clark devoted a long career to the intense manipulation of the numerous Indian tribes that came under his direct control. His career was truly remarkable because of the extremely rapid spread of the new nation in the wake of his manipulations and his reconnaissance of the plains and Pacific Northwest.

If one suspends any moral judgement on his actions, Clark’s accomplishments reach heroic proportions. But I, a direct descendent of Makes The Song, can no more suspend judgement on Clark’s incredibly cynical and immoral career than I can deny my ancestry and heritage. What if things had turned out differently that day in September 1804? We will never know.

Support Yellowstonian and

Get Some Real Cool Visual Stuff

From now through the end of July, Livingston-based Artemis Institute, the parent non profit entity of Yellowstonian, is participating in the Park County, Montana Community Foundation’s Give a Hoot fundraiser and all contributions made to Artemis Institute will support Yellowstonian‘s mission of providing conservation journalism focused on Greater Yellowstone. We would be profoundly grateful for your support and here’s your chance to get a really cool visual reward for your generosity: Anyone who contributes $35 or more will receive their pick of one individual species poster below or all three for $100. For a donation of $350 or more, supporters will receive a special, limited-edition collector’s lithograph that features all three of Greater Yellowstone’ species’s icons. It is hand-signed by Eric Junker.