by Todd Wilkinson

In this third decade of the 21st century, nature pilgrims on their way to Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks increasingly opt for air travel over the traditional method of piling into vehicles and setting out on the great American road trip. For many who fly into Bozeman, Jackson Hole or Idaho Falls from the east, what they see far below, after crossing aloft over the Mississippi, is an area of the country long treated condescendingly as “the flyover.”

How ironic that for tourists eager to see wildlife in Greater Yellowstone they’re actually overlooking what was once the richest biome in North America—the prairie.

Largely treeless, windswept, exposed to the elements, dauntingly spacious, and, until fairly recently, coated with an amazing mosaic of native plants, the prairie/high plains was home to an intricate web of life that functioned as a system constantly re-generating.

Some readers here may not realize that the check list of charismatic megafauna routinely seen in Yellowstone and Grand Teton actually comprises species that were fixtures on the prairie.

Bison (tens of millions of them), along with flowing herds of elk and bands of pronghorn, grizzly bears, wolves, coyotes, black-footed ferrets, sandhill cranes, even bighorn sheep, are products of the big open and river corridors running through. Underappreciated, too, is the prairie as a kinetic crossroads for hundreds of different bird species, many moving between breeding grounds in northern latitudes and wintering areas as far south as Central America. Add to this native insects, amphibians and reptiles, and what existed until the advent of modern industrial agricultural was both a naturalist’s paradise and a storehouse of sustenance for indigenous people. From tasty food for daily meals to herbal medicines, the plentitude dwarfed the offerings available at any modern farmer’s market or whole food store.

Not long ago, ecologist Curtis Freese, who co-founded the American Prairie Reserve (now called simply American Prairie) with Sean Gerrity and others, wrote a book, Back From The Collapse: American Prairie and the Restoration of Great Plains Wildlife published by the University of Nebraska Press. The volume delivers a comprehensive overview of why the prairie matters and sets the stage for what’s coming in the next century. Poignant, too, is that the daring, visionary efforts of American Prairie exist in parallel and some ways in contrast to the still-evolving story of wildlife conservation in Greater Yellowstone. Where the preserve American Prairie is assembling is intended to reach one and a half the size of Yellowstone National Park, the aim there is re-wilding and restoring the ecological processes in a corner of that vast biome. In Greater Yellowstone, the challenge is to prevent the region’s de-wilding through the loss of migration corridors to differing kinds of human development on both public and private lands. Simply put, the question is can public land managers along with elected officials at the federal, state and local level devise policies that “hold the line” and sustain the diversity which exists now, or will human activities continue apace, carving up landscapes into ever-smaller pieces?

Freese’s engaging book puts both the end-goal of American Prairie and what’s at stake in Greater Yellowstone in perspective. After you read it, you will never think of the prairie the same way again as you fly over it and have the delight of taking a long drive through it.

I recently interviewed Freese, who for years lived in Bozeman. He is married to noted artist Heather Bentz who served as assistant dean of the College of Arts and Architecture at Montana State University and the College of Visual and Performing Arts at University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. Bentz also worked at World Wildlife Fund for whom Freese was employed as an ecologist before joining American Prairie.

What’s the future of America’s prairie ecosystem,

the humans and wildlife living within it?

An In-Depth Conversation with Curtis Freese

TODD WILKINSON FOR YELLOWSTONIAN: Your book really opens one’s eyes and imagination to what American Prairie is trying to piece back together on its own lands in east-central Montana near the Upper Missouri River. It paints a portrait of biodiversity abundance, followed by mind-numbing, human-induced destruction and then shows us what’s possible to try to bring back through repair and protection at scale. As you note, it’s a bioregion that evolved over 500 million years yet was radically altered in just 150 years. Was this book difficult to write?

CURTIS FREESE: First, thank you, Todd, for the opportunity and honor to participate in the launch of this new venture, Yellowstonian. To your question, the writing was sometimes hard because my default style is technical writing—efficient sentences and paragraphs with little passion, few metaphors and no story telling. So I worked hard—thankfully with the help of friends and family who read my drafts—to make the book accessible, enjoyable and informative for the interested public as well as for wildlife and wildland managers and scientists.

But mostly it was deeply satisfying because I enjoyed exploring the vast literature and interviewing experts across the broad range of topics covered in the book. There is nothing more fun, for me anyway, than going down a rabbit hole to research some topic, from paleontology to recent history to the plants and animals of the Great Plains, even if most of it didn’t end up in the book. The problem is, at the end of some days doing this I’d think, damn, did I write even one sentence? Better stop testing my editor’s patience. I should add here, before proceeding, that neither in my book nor here do I in anyway speak for American Prairie. These are strictly my personal take on things.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Frank and Deborah Popper, who conceived of Buffalo Commons in 1987, were just in Bozeman. They laud American Prairie and describe it as “Buffalo Commons adjacent,” meaning that while it isn’t Buffalo Commons it is an expression of how prairie ecosystems can be restored. How did the idea of Buffalo Commons affect the thinking of you and Sean Gerrity when American Prairie was only an abstract concept?

FREESE: The Poppers’ “Buffalo Commons” made our concept of building a 5,000-square-mile prairie reserve look modest! I won’t try to speak for Sean [Gerrity], but from my perspective their 1987 paper, in which they propose the idea, provided a much-needed, clear-eyed, wake-up call to everyone, from ranch communities to conservationists to rural policy wonks, that the 100-year experiment of Euro-American settlement of the Great Plains was floundering. By the time we launched American Prairie in 2001, the 1990s had experienced a continuation of what the Poppers described—the continuing 100-year decline of the human population of eastern Montana’s rural counties. The Buffalo Commons was also a reminder of the tragic loss the Great Plains suffered when tens of millions of bison and other wildlife—along with Indigenous people—were annihilated by Euro-American settlement. The vision of American Prairie was one small step toward righting that wrong. Buffalo Commons provided an opening and justification for re-envisioning what the prairies of eastern Montana—and more broadly the Great Plains—could be economically, culturally and biologically.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Some might not know that earlier in your career you worked internationally for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service overseeing its Latin America program, served as vice president of conservation programs for World Wildlife Fund in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and, as a conservation ecologist you’ve been involved with leading edge discussions about re-wilding. Based on your global perspective, what do you think Americans take for granted about the prairie?

FREESE: It begins with their assumption that the prairies are boring flyover country and were made for crops and livestock…and always will be. That the era of creating big parks in the Great Plains passed years ago. That you’ll only ever know about the Serengeti-like wildlife spectacle of the Great Plains by reading early explorers’ accounts. Chalk it up to a short attention span that ignores both history and harbingers of the future.

An alternative, dynamic view of the Great Plains is that in 50 years we will have three major land uses there: crops, livestock grazing, and wildlands. History tells us that such massive change should be expected. Almost any 30 to 50-year period in the Great Plains over the last 200 years experienced similarly big transformations: from Indigenous to Euro-American-dominated land management; a near total swap from native ungulates to livestock; the rise and fall of the cattle barons and open-range grazing; the homesteading surge of people followed by their massive exodus and government’s land buyback program; no farm subsidies to billions of dollars in subsidies; and more. The Great Plains has seldom been locked for long in one economic or land-use mode over the last 200 years.

YELLOWSTONIAN: With big changes coming that disrupt the way agriculture has been tiered to “predictable” seasonal weather patterns, it will bring seismic economic and social implications for prairie dwellers. What else do you see? [Note to readers: scroll to the bottom of this interview and take note of Freese referencing four different numbers: “24,” “95,” “5,000,” and “2”]

FREESE: The next 50 years is likely to bring an even faster transformation in how our prairies are managed due to climate change, groundwater depletion, market forces, food technology, public attitudes, and so on. Examples: Jerry Holechek, professor at New Mexico State University, recently expressed the view of many leading rangeland scientists when he and colleagues wrote, “Eventually, traditional ranching could become financially unsound across large areas if climate change is not adequately addressed.” Per capita beef consumption in the U.S. has declined by a third since the 1970s. A recent review of 30 public opinion surveys in the West found that, on average, western voters back proposals to expand federally protected lands. Many will disagree, but I see transformational change on the horizon. The uncertainty is in what sectors it will happen first and at what scale.

YELLOWSTONIAN: From a conservation perspective as it pertains to restoring and protecting biodiversity as an attempt to tangibly bolster resilience, it’s not all woeful. You’re not being insensitive to the people and multi-generational rural people who live there now. The sense I gather is that you foresee a future in which the changing land will re-form culture rather than forcing land to conform to the kind of monoculture uses imposed upon it.

FREESE: Let me share a lesson from my international experience that involved a country changing the way it thinks about nature. In 1970, a year before I began working for the Costa Rican Park Service, Costa Rica created its first national park, Poás Volcano National Park. Thirty years later, Costa Rica had one of the premier protected-area systems in the world. In the process, Costa Rica transitioned from a deforestation-enabled economy based primarily on agricultural exports to a more diversified and resilient economy that depends on forest protection and restoration to support a multi-billion-dollar nature tourism industry and to protect watersheds for human consumption, hydropower and irrigation. We saw a similar surge in protected area growth in other countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia. So my view was that if conservationists in countries with growing and impoverished human populations, much more limited resources, and bigger, scarier wildlife than we have are willing to try and often succeeding in building big protected areas, we can surely do the same in the Great Plains. The result will be a transformation from a landscape dominated by monocultures of crops and livestock to one where wildlands are another major land use delivering multiple societal benefits from biodiversity, watershed protection and outdoor recreation to soil conservation, carbon sequestration and resiliency to climate change.

“My view was that if conservationists in countries with growing and impoverished human populations, much more limited resources, and bigger, scarier wildlife than we have are willing to try and often succeeding in building big protected areas, we can surely do the same in the Great Plains. The result will be a transformation from a landscape dominated by monocultures of crops and livestock to one where wildlands are another major land use delivering multiple societal benefits from biodiversity, watershed protection and outdoor recreation to soil conservation, carbon sequestration and resiliency to climate change.”

Author and scientist Curtis Freese

YELLOWSTONIAN: People driving along Interstate 90 or 94 between Minneapolis/St. Paul and Seattle may think the prairie is empty, boring and even desolate. Your book will quickly disabuse them of that. It’s like standing next to the ocean and not realizing what’s beneath the waves. What folks may not understand is that between American Prairie, wildlife migration mapping done by the Wyoming Migration Initiative and the marvel that is Greater Yellowstone, our region is seen as a conservation bellwether for big picture thinkers around the world. The purpose of wildlife conservation seems obvious here. You are an Iowan by birth and rearing. How does that shape the way you think about the heartland, the Great Plains and the prairie?

FREESE: I was born and raised on a farm in the tallgrass prairie region of eastern Iowa. Growing up hunting pheasants and trapping muskrats led me to believe a grassy draw or shrub-lined creek winding through a cornfield was great wildlife habitat. A couple of courses as an undergrad in wildlife biology at Iowa State University set me straight regarding the almost total loss of the tallgrass prairie and its wildlife. Fortunately, millions of acres of mixed- and short-grass prairie remain in the more arid western Great Plains, but we’re still losing nearly two million acres of Great Plains grasslands to the plow every year. So I feel urgency in ensuring that our remaining prairies don’t suffer the same fate as the tallgrass prairie.

YELLOWSTONIAN: American Prairie is thought of, by some people who dwell in the western mountains of Montana and Wyoming, as “that experimental-thing happening way out there somewhere” in the windblown country. What should interest Greater Yellowstone residents is that there’s a strong connection between Jackson Hole and the C.M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge which is a bordering neighbor of American Prairie. The conduit is naturalist Olaus J. Murie (1889-1963), known for his pioneering work on elk, his advocacy for expanding the size of Grand Teton National Park, his promotion of wilderness protection and preserving the Arctic in Alaska. How does Murie fit into the focus area of your book? Anything that leaps out at you from Murie’s report?

FREESE: In 1935, Murie, while employed by the Bureau of the Biological Survey (today’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), wrote Report on the Fort Peck Migratory Bird Refuge, based on his biological survey of the area surrounding the construction of the Fort Peck dam that was then underway. Although Murie gave the most attention to the sharp-tailed grouse because he considered it “the most important bird affected by the plan for the refuge,” I found two other comments more interesting.

With his qualifier of “I am not at all sure of the desirability of introducing bison,” he had to admit that “It is a rather alluring thought for the outdoor-man to restore the bison to a portion of its hereditary range in this part of Montana” and “that there would be much value in such a move, of an inspirational sort.” Also notable was that among the region’s ranchers he “found considerable sentiment in favor of a wildlife refuge . . . and some of them were very enthusiastic.” Some, he noted, “begged us to push the refuge idea vigorously.” Makes one wonder if the Montana Stockgrowers Association might learn a lesson from old-time ranchers about showing some magnanimity toward protected areas.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Murie, who was one of the foremost biological thinkers in the country at the time and a friend and colleague of Aldo Leopold, had also supported better protection of the Gallatin Range between Bozeman and Yellowstone because of their high wildlife values. What few realize is how Murie’s thoughts informed the perspective of US presidents in how they thought about Greater Yellowstone, Alaska and the landscape where today American Prairie is doing its work.

FREESE: Yes, Murie’s report provided the foundation for president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1936 executive order creating the Fort Peck Game Range (now the C.M. Russell Refuge), one of the most important wildlife conservation acts of his presidency. Although it’s too bad he didn’t mandate reintroducing bison at the same time.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Perhaps because the prairie offers a kind of topographic drama that is very different from the kind of eye that exists in the mountains with peaks jutting into the sky, it is more difficult for some to fully appreciate the intricate, mesmerizing web of interconnections between native species. What are a few of the favorite examples you use to make this point?

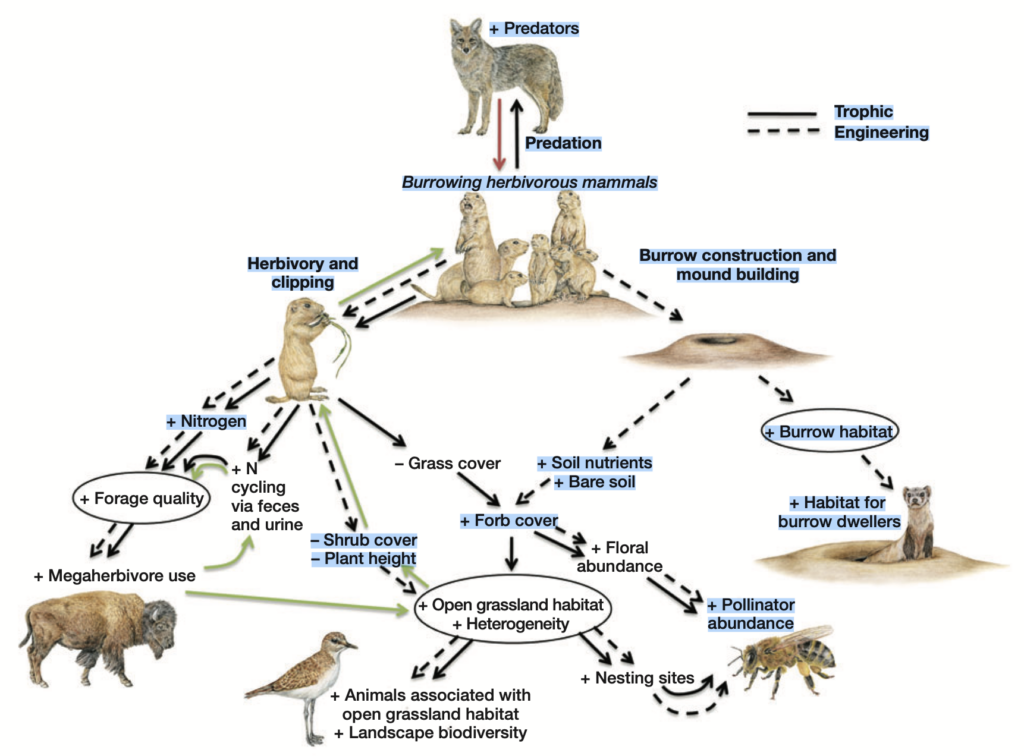

FREESE: I’ll pick two of the best-known, most-studied species on the prairie—prairie dogs and bison—because they illustrate so well that just when we think we fully understand their role in the ecosystem, they surprise us with new revelations.

The prairie dog, as most of readers likely know, stands out for its ecological interconnectedness—their burrowing churns the soil and creates habitat for subterranean species, species ranging from bison and pronghorn to mountain plovers and thick-billed longspurs eat the plants and insects that thrive on their colonies, and their plump bodies attract a menagerie of avian, mammalian and reptilian predators. But new connections are still being discovered. Recently, for example, Rick Adams at the University of Northern Colorado found that several species of bats were foraging at night over prairie dog colonies, apparently because the colonies support an abundance of flying insects. The activity pattern of one species, the small-footed myotis, even suggests that they may use the burrows as roosting sites! I now realize that it was likely not a coincidence when I once saw several common nighthawks foraging over a prairie dog colony on American Prairie lands.

YELLOWSTONIAN: And, as for the signature icon of American Prairie—bison—elaborate, please, on the animal’s importance as an ecological driver.

FREESE: Bison offer another lesson in interconnectedness because we tend to focus on just one end of the bison, that is, what goes into their mouth and much less on what goes out the other end. No doubt, bison grazing and its interaction with other grazers and with fire is extremely important for supporting the diversity of plant species and of habitats that grassland birds and other wildlife depend on. But an ecological dictum is “follow the nutrients.” And bison dung has a load of nutrients. Lucky for the grassland ecosystem, lots of small organisms know this. One bison will drop 10–12 dinner-plate-size patties per day. Each new patty instigates a feeding frenzy of insects, nematodes, bacteria, fungi and other tiny organisms.

So, first, you have this incredible biodiversity within the patty itself. Three hundred species of insects may inhabit a single patty and surely thousands of species of microorganisms. All this biological activity eventually returns nitrogen and other nutrients to the soil for plants to use. Now consider that a bison population of 1,000—about the size of American Prairie’s—deposits four million patties in a year. What a biological circus—mostly invisible to us! But that’s not the end of the dung story. Bison disperse plant seeds in their dung—at least 70 species of seeds found in one study. Long-billed curlews often build their nests next to bison patties, perhaps as a form of camouflage. Burrowing owls line their underground nests with bison dung to attract dung beetles that the owls feed on. What else is there yet to be discovered about bison poop?

YELLOWSTONIAN: As a result of your research, what were the lifeways like for indigenous people on the prairie prior to the return of the horse and the arrival of firearms?

FREESE: The lesson from my research is that I would not even wish to try to describe their lifeways, whether before or after the arrival of the horse and firearms. What I can say is that I appreciate that indigenous lifeways on the prairies surely reflect a complex co-evolutionary dance of Indigenous peoples with the prairies and prairie wildlife over the last 20,000-plus years. This spans the transition from a mostly forested region to today’s grasslands, the massive extinction of large mammals (mammoth, short-faced bear, etc.) at the end of the Pleistocene 12,000-some years ago, and the peak and then retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet from the northern prairies, among other sweeping changes. After more than 20,000 years of adapting to this ecological maelstrom, Indigenous peoples surely have myriad lifeways I am clueless about!

YELLOWSTONIAN: You make glowing, reverential reference to the work tribes are doing. You note how, in many places, they are positioning their communities to be at the forefront of using bison as a keystone for healing land, improving human health and preserving culture. What most excites you?

FREESE: I’m excited by how ecological research is confirming the land-healing power of bison. That, in turn, offers ever better reasons for restoring the bison to its keystone role in the prairie ecosystem by rewilding millions of acres of the Great Plains. New studies demonstrate how we’re still learning their land healing ways. Recent research by Zak Ratajczak and colleagues found that re-introducing bison to a tallgrass prairie site resulted in a doubling of the number of plant species. This was double the increase recorded after the introduction of cattle. Moreover, the plant-species-rich bison site was much more resilient to the effects of a severe drought than the ungrazed and cattle-grazed sites.

YELLOWSTONIAN: You’ve not mentioned any need to pepper bison country with pesticides, herbicides and nitrogen-rich fertilizers.

FREESE: Let me bring up dung and dung beetles again to demonstrate the subtleties of land healing. Not just any dung will do for a dung beetle. When cattle replaced bison, non-native dung beetles were introduced and began to replace native dung beetles. Recent research by Ellen Welti, a scientist with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, found that when American Prairie replaced cattle with bison the non-native dung beetles disappeared while nine native species have claimed the dung. It’s an encouraging case of native species returning and self-assembling on their own, with surely profound benefits, yet to be fully understood, for nutrient recycling in the prairie ecosystem.

I’ve been lucky to witness another healing effect myself. American Prairie replaced cattle with bison on their Dry Fork Unit in 2016. Beaver Creek, which runs through the area, was a highly incised narrow channel with scant beaver activity. This is often the effect that intensive use and trampling by cattle, combined with beaver removal, has on small prairie streams. Bison, in contrast, come much less frequently to water. Now, a mere eight years later, the beaver population has boomed as they’ve built 100-foot-long dams and created extensive wetlands on Beaver Creek attracting wetlands plants and wildlife. It’s been a phenomenal transformation to watch.

YELLOWSTONIAN: The late great ecologist E.O. Wilson wrote about “consilience” and made a case for demonstrating there is no insurmountable chasm separating having a scientific understanding of the natural world and one that involves having a spiritual relationship. As an expression of this, how has the holistic thinking of indigenous people affected your own views?

FREESE: When we released the first 16 bison onto American Prairie lands in 2005, George Horse Capture, Jr., a spiritual leader of the Aaniiih Nation on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, gave a blessing. After listening to George and other Indigenous people share stories of their spiritual connection to bison and the land, and George’s invitation for all of us to nurture that same connection, I’ve increasingly appreciated and respected that view. Though I don’t consider myself particularly spiritual—not in the religious sense anyway—I view bison science and the spiritual reverence for bison synergistically fitting side-by-side to justify and foster the restoration of wild bison.

YELLOWSTONIAN: What do you better appreciate about bison today that you’ve absorbed from experience and didn’t grasp when you were a young ecologist in your 20s and 30s?

FREESE: I was mostly a tropical ecologist and conservationist in my 20s and 30s and so my grasp of anything bison was nil then. Although bison had been gone from my home ground of eastern Iowa for more than 100 years, I did have an early experience with wild bison when I worked as a biologist in Yellowstone National Park during the summers of 1969 and 1970 before I left for the tropics the next year. What I mostly grasped then as a young, naïve wildlife student was that bison were big and intimidating up close—a wonder to behold—but I knew almost nothing about their ecological role. But, if you look at the history of ecological research about bison, essentially no one else did either except that they were obviously prey for wolves and grizzly bears. Considerable research over the last three to four decades, however, has demonstrated the central role that bison play in shaping the grassland ecosystems of the Great Plains, with new insights to their importance still being discovered. Our grasslands are profoundly different places both culturally and ecologically without them.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Anything more you wish to throw in here about the ecological value of those two other keystone species you mentioned earlier—beaver and prairie dogs?

FREESE: Most people recognize the ecological value of beaver, but few likely appreciate that their keystone role is magnified in the semi-arid Great Plains compared to their influence elsewhere across the continent. Whether in the humid east, mountain west, or boreal north, streams still generally flow and water is not in short supply even when beaver are gone. But not so in the short- and mixed-grass prairies of the western Great Plains. Here, beaver dams are crucial for capturing and holding stream water in beaver ponds and recharging groundwater, water that without beaver would be gone by mid-summer, leaving the riparian vegetation and wildlife high and dry and dying. Beaver-dammed streams are lifelines into the semi-arid grasslands of the region.

I could wax on and on about the ecological value of prairie dogs, but probably said enough already except, perhaps, to emphasize that we need colonies of tens of thousands of acres to fully appreciate their ecological and cultural value. We are nowhere near that anywhere yet.

YELLOWSTONIAN: It’s a term that is thrown around with wild abandon. When you hear the term “regenerative agriculture,” what does it mean to you?

FREESE: Because it means a lot of different things to different people and there is no legal or regulatory definition of it, what I think it means and how it’s practiced may be two different things. This seems especially true with respect to regenerative grazing as I see a diversity of grazing practices using this label. Restoring soil health seems a fairly constant goal, but the outcomes for biodiversity appear much more uncertain. I’ve seen as a goal, for example, grazing to a uniform vegetation height and the elimination of bare ground, neither of which is good for native grassland biodiversity. The best regenerative grazing is to replace livestock with prairie dogs and wild ungulates—bison, elk, deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep—and give them lots of room to roam!

YELLOWSTONIAN: No pun intended but dig deeper into regenerative farming because to many readers here it might be obscure. And yet, a lot of different entities are engaged in. Ted Turner, who owns a couple of bison ranches in southwest Montana, has created the Turner Institute of Ecoagriculture and is advancing principles of re-generative ag at bison ranches in South Dakota and the Sandhills of Nebraska. It’s working with the Center of Excellence for Bison Studies at South Dakota State University. There’s also the Intertribal Buffalo Council comprised of over 80 tribal nations in 20 states, which is working closely with Yellowstone National Park.

FREESE: The focus in regenerative farming also seems to be on restoring soil health and carbon. But let me take the opportunity to riff on a favorite gripe. I also hope it means that we get rid of ecologically and economically perverse crop subsidies, encourage greater diversity in food production, stop sodbusting of native prairie, and restore prairie on lands that should never have been cultivated. Speaking of subsidies, northeast Montana is among the biggest recipients of this government largesse in the country. Since 1995 farmers in the eight-county region of American Prairie have received more than $3 billion in subsidies. What did that buy?

World Wildlife Fund’s Plowprint analysis shows that from 2009 to 2020 nearly one million acres of grassland were converted to cropland in the region, the equivalent of 8 footballs field per hour. Much of this acreage is, at best, marginal cropland that should have never been plowed, but crop insurance subsidies that we pay for mitigate the risk. The result—apart from converting a rich grassland ecosystem to a biodiversity wasteland—is the erosion of vast amounts of soil and nutrients that eventually augment the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, the release of tons of global-warming carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide into the atmosphere, and widespread applications of wildlife-poisoning neonicotinoid insecticides. For much of this cropland, the best regenerative practice would be to regenerate native prairie.

World Wildlife Fund’s Plowprint analysis shows that from 2009 to 2020 nearly one million acres of grassland were converted to cropland in the region, the equivalent of 8 footballs field per hour. Much of this acreage is, at best, marginal cropland that should have never been plowed, but crop insurance subsidies that we pay for mitigate the risk.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Regarding climate change, please share a few of the wowing insights in your book about how much carbon a healthy diverse grassland ecosystem sequesters. And its role in strengthening the resiliency (hardiness) of a region facing shocks of hotter drier temperatures, erratic precip that departs from the predictable norm and certain human hardship.

FREESE: Grasslands of the world store one-third of global terrestrial carbon stocks. Because 90 percent of that is stored underground, it’s generally less vulnerable to carbon loss than forests, which have most of their carbon stored aboveground. Thinking at a smaller scale, one acre of tallgrass prairie may store one ton or more of carbon. However, plow that prairie for cropland and within a few years more than half of that carbon will likely be lost to the atmosphere as global-warming carbon dioxide, as well as some to soil erosion.

Greater plant diversity generally results in more sequestration of soil carbon. Grasslands with native plant diversity are highly adapted to the boom-and-bust weather conditions of grasslands. Research in grassland ecosystems suggests that there may be as much as a 10-fold difference in tolerance to drought among the roughly 80 species of grass found in the American Prairie region. So during extreme droughts, highly drought tolerant species thrive while, during wet periods, species that are less drought tolerant dominate. The bottom line: compared to cropland or tame pastures with few grass species, the high plant diversity of native grasslands assists in the battle against climate change by both storing more carbon and by being much more resilient to the climatic extremes that the region is experiencing.

YELLOWSTONIAN: I don’t mean to pick on the media, but journalists who are members of my own professional tribe seem, especially those who parachute in from outside the region, fairly regularly fall into the trap of resorting to “bothsidesism” in creating their story line. Narratives often portray anointed villains vs. anointed heroes and highlight a polemic which pits American Prairie supporters against detractors. The truth is that, whether AP existed or not, the huge existential problems facing struggling mom and pop ranchers and farmers would still be deepening. Worry about change, the pain that accompanies loss of community, and fear of the unknown are very real, but it seems to get misdirected and not often explored much by journalists. Your thoughts?

FREESE: I agree, Todd. Most journalistic stories I read about American Prairie are real yawners because they rehash the same rewilding-versus-rancher story line that we’ve read dozens of times before. The setup for these stories is efficiently captured in the signs one sees posted in northeast Montana that say “Save the Cowboy, Stop American Prairie Reserve.” As Mark Twain commented, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.”

“Most journalistic stories I read about American Prairie are real yawners because they rehash the same rewilding-versus-rancher story line that we’ve read dozens of times before. The setup for these stories is efficiently captured in the signs one sees posted in northeast Montana that say ‘Save the Cowboy, Stop American Prairie Reserve.’ As Mark Twain commented, ‘Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.’”

Curtis Freese

The truth is that the biggest threat to ranching is climate change, loss of millions of acres of rangeland to cropland and tree invasion, invasive plant species, declining per capita consumption of beef, limited means to diversify ranch income, and young people leaving in search of better opportunities, to name the most prominent. I’ve read a lot of peer-reviewed analyses about threats to Great Plains ranching and ranch communities, but wildlife reserves have never come up as one. In fact, American Prairie offers at least some help for local communities by diversifying economic, cultural and recreational activities in the region and putting more people to work. An indicator of this is that American Prairie and the Smithsonian Institution, which has a research team on the reserve, face a housing shortage. More staff and their families live on the land and in local towns and shop in local stores than would be the case if all the land was still in livestock ranching. But, hey, why let the facts get in the way of a good they-versus-them story?

YELLOWSTONIAN: We like the truth over whatever the alternative to truth-telling is. The organization United Property Owners of Montana, which is behind the distribution of those “Save the Cowboy” signs has made several assertions that do not hold up to serious journalistic scrutiny. It also has opposed the Bureau of Land Management allowing American Prairie to lease public land for bison, arguing the agency should give primacy to non-native cattle. The same entity seems to have no problem with wealthy folk from Texas buying up mom and pop ranches in Montana and doing the same things that UPOM claims American Prairie is doing.

FREESE: This is a good place to add that the vast majority of landowners in the region do not post “Save the Cowboy” signs. Instead, many ranchers as well as the people on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation are wonderful partners working with American Prairie to restore the prairie and its wildlife.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Society, which includes the funders of government (i.e. taxpayers) and the private sector have spent billions of dollars and will spend a lot, lot more in years to come trying to fix broken ecosystems and put them back together again. Whether it’s taking down dams to rescue salmon from extinction, or trying to re-engineer the Florida Everglades, or even building an $80 million overpass across 10 lanes of traffic in southern California to help a tiny population of mountain lions and other species move between remnant habitats. What’s daunting to you about “restoring the prairie?”

FREESE: First, the good news is that, given enough time and space, full restoration of the prairie ecosystem and its native species is highly doable. (Except for the likely extinct Rocky Mountain locust.) Comprehensive restoration, with free-roaming bison, migratory pronghorn, wolves and grizzly bears, and similar wide-ranging species requires millions of acres as a core area and millions of surrounding acres with wildlife-friendly landowners and ecological connectivity to other wildlands, so assembling the land and community cooperation are crucial and daunting tasks. As I noted above, the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and many local landowners, such as those participating in American Prairie’s Wild Sky Program, are solid and inspiring collaborators with American Prairie and the C.M. Russell Refuge in this effort. The task is much less daunting when working together.

Some species restoration needs pose special challenges. Perhaps the most challenging is overcoming plague, a disease of Asian origin, that is deadly to prairie dogs and thus is a hurdle to restoring big prairie dog colonies and their keystone role in the prairie. No species’ survival depends on this more than the black-footed ferret, one of the most endangered species in North America.

Imperiled prairie species: Short-eared owl, Greater sage-grouse hen, and marbled godwit. Photos by Curtis Freese

YELLOWSTONIAN: As for the feathered denizens who breed on the prairie, live there or use it during pitstops?

FREESE: A major daunting challenge is trying to restore or stabilize grassland bird populations, which have been undergoing steeper declines than any other group of birds in North America. In this case the problem is that grassland birds migrate to spend winter in the grasslands of the Chihuahuan desert and other regions to the south and southwest. So stopping and reversing these population trends require large-scale conservation work—saving and restoring habitat, controlling insecticide use, and other measures—on both their nesting and wintering habitats as well as at stopover sites along their migration routes.

There are many unknowns because we lack the resources to adequately monitor trends in species populations and other indicators of ecological health. For example, some data suggest that pollinators—hundreds of species of bees, butterflies and other insects—may be trouble. If so, what are the consequences for prairie biodiversity and for agriculture?

YELLOWSTONIAN: We, of course, value your perspective on Greater Yellowstone where you were based for a few decades. Here, we presently have wildlife completeness and landscape intactness—the best, in fact, compared to anywhere else in the Lower 48. But intense human pressures are causing a fraying at the edges and on crucial private lands. You and your artist wife, Heather Bentz, lived in Bozeman as it was growing and you’re familiar with huge growth issues in Jackson Hole, Big Sky, Teton Valley, Island Park, Idaho et. Now the rate of change has brought an acceleration of expanding human footprint. What’s your advice for people who live in Greater Yellowstone and or who like visiting but aren’t aware that our legacy could be one of de-wilding?

FREESE: Anyone who visits national parks in the West quickly recognizes two problems, for which Yellowstone could be the poster child. The most obvious is overcrowding of the parks themselves—the “loved-to-death” syndrome. The second is people crowding around the perimeter of parks to live on private lands and recreate on public lands. The obvious advice is don’t build your house in wildlands that wildlife depend on and recreate with a light touch. What should be equally obvious is the importance of voting and lobbying for legislators, governors, policies and budgets that support the park and the wild nature of the lands and waters that surround it. Do not take it for granted, do not assume others will take care of it. It demands commitment and work to keep what you have and love.

“Anyone who visits national parks in the West quickly recognizes two problems, for which Yellowstone could be the poster child. The most obvious is overcrowding of the parks themselves—the “loved-to-death” syndrome. The second is people crowding around the perimeter of parks to live on private lands and recreate on public lands. The obvious advice is don’t build your house in wildlands that wildlife depend on and recreate with a light touch.”

Curtis Freese

YELLOWSTONIAN: Back From The Collapse deposits readers into the middle of the prairie and takes stock of what’s been lost or depleted. You do a marvelous job providing an overview of what American Prairie is endeavoring to do and this part of your narrative is hopeful. Yet you are not a Pollyanna. You call out the reckless heavy-handedness that turned this biome on its head. As a seasoned scientist you make a strong case for why we need to change our ways as a society. It’s inspiring to see your passion. What prompted you to take this tone?

FREESE: In large part, numbers did, and I’ll offer you these:

“24”—At a minimum, the number of species in northeast Montana whose populations collapsed by at least 90% after Euro-American colonization. As I describe in my book, some are still barely hanging on, some are still declining, a few have partially recovered, and, because my estimate was conservative, the number that have collapsed is probably closer to 30 or more.

“95” —The estimated percent of all non-human mammalian biomass in Great Plains grasslands that consists of livestock, versus 5% that is wild mammals. Plus, consider that all of that 95% gets removed from the landscape rather than, as occurred historically, remaining there to feed predators, scavengers, decomposers and plant life. It’s one ecological reminder, among others too long to describe here, that while good practices in livestock ranching can make important contributions to conserving grassland biodiversity, it represents a highly distorted ecological system far removed from natural conditions that in no way can substitute for large protected areas.

“5,000”—The square-mile goal of American Prairie for which the 1,500-sq-mile Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge provides a central anchor. While small protected areas are also crucial, we need a series of similarly large protected areas across the Great Plains to fully restore and conserve the region’s wildlife, to rewild the landscape, to bring wonder and awe to future generations.

“2”—The percent of the Great Plains in protected areas dedicated to biodiversity conservation, compared to an average of 24 percent for the other biomes of the United States. In 2016, the directors of NPS, USFWS, USFS and BLM, along with the heads of their counterpart institutions in Canada and Mexico, signed a report calling for increasing protected area coverage of North America’s central grasslands to 17 percent, or roughly 100 million acres of new protected areas for the Great Plains. Remarkably, here we have federal agencies taking the lead with a bold proposal, but the conservation community has mostly ignored it. With a more lenient definition of what counts as protected, in 2021 President Biden issued an executive order pledging to conserve 30 percent of the U.S.’s lands and waters.

YELLOWSTONIAN: In Greater Yellowstone and other places, there is a sense that the conservation movement has drifted away from wildlife conservation, even in some cases demonizing the value of protected areas, at a time when stronger advocacy is most needed.

FREESE: I am perplexed and concerned that much of the Great Plains conservation community is ignoring protected areas. If you doubt that, do a word search for park, refuge, reserve, wildland, protected area or any similar term of the Central Grasslands Roadmap, the biggest grassland conservation initiative, in terms of participating institutions, underway today. It seems like it would require a conscious effort to avoid talking about protected areas in the document. My reading is that much of this inattention to protected areas stems from the belief that because 90 percent of the land is privately owned that little can be done for protected area expansion (though that doesn’t explain the inattention to helping existing protected areas). I also wonder if an undercurrent here is fear that promoting protected areas will jeopardize cooperation from the ranching community. I disagree with the first premise. And if the second is true, it’s a sad state of affairs if we can’t embrace both concepts at the same time: both protected areas and biodiversity-friendly ranching practices are crucial and must work side-by-side for successful biodiversity conservation.

As I noted above, it seems likely that big changes will sweep across the Great Plains over the coming decades, changes that may offer a chance for wildlife, from dung beetles to bison to wolves, to return to their native home on the prairie and to reverse the ongoing collapse of other wildlife populations. American Prairie and its diverse collaborators provide an inspirational touchstone for realizing this vision by rewilding landscapes large and small elsewhere in the Great Plains. The last chapter of my book argues that money is not the problem—a fraction of cropland subsidies could pay annually for a million acres of land acquisition and management. A win-win: rather than subsidize prairie plow-up, use the money to save and restore prairies. What’s lacking is the will to dream and act at much larger scales, at scales that are visionary, at scales that grab public attention, at scales that matter to wildlife.

YELLOWSTONIAN: Thanks for the fantastic conversation and, on that note, we’ll end for now. Again, we hope readers will pick up a copy of your book Back From The Collapse: American Prairie and the Restoration of Great Plains Wildlife.