by Thomas D. Mangelsen

You may remember how I won a hunting tag in a Wyoming lottery, giving me “the right” to kill a grizzly bear. It was all part of the state’s first proposed sport hunt of grizzlies in over 40 years.

I was excited to be a “winner” of the tag. Of course, I had no intention of taking the life of a bear with a bullet. Like so many of us, I am deeply moved by the fact that as sentient marvels of creation, grizzlies have an “intrinsic value” that makes them worth far more alive than dead. Instead of cleaning my rife and buying bullets, I allied myself with a group of impressive women in Jackson Hole who had created a grassroots initiative called “Shoot’Em With A Camera.”

It’s a concept that my friend Tim Mayo and I had thought of, independently, too. As the name sounds, the point was to show the public and officials in the state that a substitute option existed—an alternative to treating grizzlies as trophies destined to become dead “decorative objects” in somebody’s man cave or game room.

Had Wyoming’s hunt commenced, I would’ve been among 21 other lucky recipients of a bear tag from among a pool of thousands who had entered the lottery. My intent was to enlist a hunting guide and invite other nature enthusiasts to join me on a trek into the wilds looking for grizzlies—and then, if we saw one, have all of us take photographs of the bear with our cameras.

Fortunately, the hunt was stopped at the 11th hour thanks to a successful lawsuit brought by the environmental legal firm EarthJustice. The legal victory resulted in grizzlies being put back under federal protection of the Endangered Species Act where they remain today. However, some politicians are pushing to force delisting and would result again in states trying to bring back sport hunting.

That’s a topic for another day. This column relates to my own motivations as a nature photographer. It’s never my primary interest to “stalk” wildlife in order to bring them into my viewfinder. My biggest delight is putting myself into a position so that animals can reveal what they want me to see.

Back in the 1980s, when grizzlies had nearly vanished from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, I often headed north to Canada and Alaska seeking to catch more readily-available glimpses of both brown bears and polar bears in the wild. A favorite destination was the McNeil River on the Alaska Peninsula where brown bears converged every year to feast upon spawning salmon. This was long before the advent of digital camera technology. My equipment then was old-school. By hand, we’d load rolls of film into the camera carriage and then have to wait to see how well we did in capturing moments. In some ways, the waiting for film was more fun.

Many of you are aware that one of my proudest images from those years in Alaska is the picture “Catch of the Day” that features the moment an airborne sockeye salmon, attempting to leap over rapids, flies into the open jaws of bear.

Nothing about “Catch of the Day” could have been rigorously choreographed by me. Rather, I had to put myself into position, and wait, wait, wait, hoping, waiting more, and praying for magic to happen. It did, but for every day like that there are countless others when the forces of the cosmos fail to align.

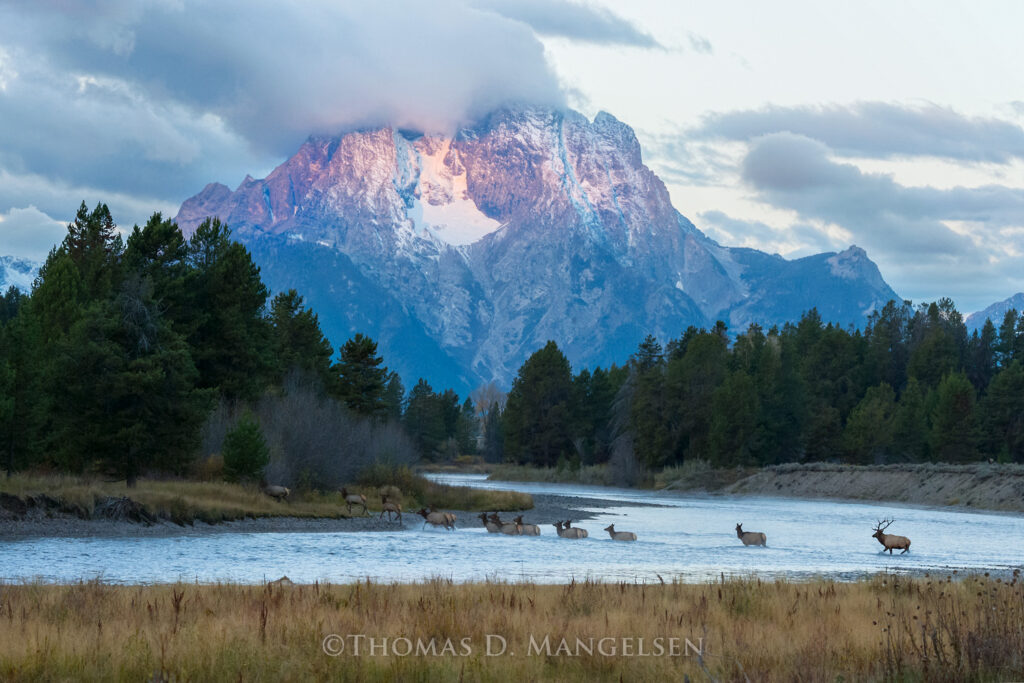

This is the way it’s been with so many other pictures. With “First Light—Grizzly” and “First Light—Elk,” I had pre-visualized what was possible but success depended on having a number of different variables converge and literally fall into place. Among them: the rise of Mount Moran, a Teton peak, in the background, with the Snake River creating a compositional element in the midground. On top of that was the most difficult part, patiently anticipating when a bear or wapiti, respectively might emerge from the forest, wade into the river and create a stunning focal point. These were the essential ingredients but crucial, too, were weather conditions and effects of light that added key components of atmosphere.

Something similar occurred with the tiger picture, “Light in the Forest,” and the portrait of waltzing polar bears, “Polar Dance,” and, yes, with a handful of photographs involving Grizzly 399, her cubs and other bears in Jackson Hole.

There is no way a human can “force” all of the individual parts to converge—unless, of course, you go to a game farm where captive animals are rented out and pose for the camera like fashion models. The challenge is being in the right place at the right time. Important to note is that in each instance I needed to be far enough away to respect the space of animals and be discreet and unimposing as to not spook them. This is the antithesis of aggressively “stalking” or trying to ambush subjects in ways that traumatize them.

On countless mornings after I arose well before dawn, nothing happened in terms of the composition I desired. And yet, while I didn’t “get the picture,” I still had the gladness of simply being out there. That’s the secret, friends. When you are out there, you never know when enchanting moments are going to reveal themselves. I love to be surprised. This to me is the essence of finding joy as a photographer. The best images are those you don’t count on. There is never a “bad” day when you surrender yourself to the whims of wild nature. Although I confess that the day 399’s young cub, Snowy, was struck and killed by a car and the day when Grizzly 610 almost died in a hit and run were sad and traumatic for many of us.

Looking back, I think an even better name than “Shoot’Em With A Camera” is “Save

‘Em With A Camera.” If you take pictures of wildlife, make sure you do it respectfully by giving your subjects the safe space they need, but also let them be your statements of advocacy for wildlife. Good luck, be safe and support conservation.