by Dennis Glick

Before tuning out the mind-numbing barrage of political ads we’ve been subjected to this year, I noticed that a major issue highlighted in many of them is the topic of more “access” to our public and private lands—who it’s for, and who’s against it.

Of course, none of the candidates are foolish enough to say anything that sounds remotely anti-access. Clearly, public polling has underscored that it’s a sacred cow in Montana, my home state. To question it would be political suicide.

Conservation organizations have also jumped on the access bandwagon. Groups that used to have tag lines and mission statements primarily focused on conservation, with an emphasis on wildlife conservation, now include access as one of their top—if not primary—goals.

Not long ago, a representative of one of Montana’s major conservation groups wrote an op-ed touting a proposed land exchange and trail-building project in the Crazy Mountains. The Crazies represent one of the northern flanks of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and the landscape surrounding it is considered a vital biological linkage zone between Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem. That landscape is also a remnant home for species found in few other states beyond the Northern Rockies.

Tellingly, in the op-ed written by the conservation group, the word “access” appeared 20 times. The word “wildlife” appeared just once. It was a sign of the times. For wildlife, of course, the land is their home—the place where they live permanently and struggle to survive. For increasing numbers of humans, it is becoming a playground. The issue is not one of “balance,” which in the equation of human wants versus wildlife needs has obviously been tilted in our favor.

As an avid hunter and outdoor recreationist, I am all for maintaining, and where appropriate, expanding, access to both public and private lands. “I ain’t no fortunate son,” as John Fogerty sang. If it’s not Block Management [private land open to public access], or public land, chances are I’m not going to be hunting or hiking it. And I’ve had more than my fair share of flushed birds, pronghorn, and other game I’ve been pursuing fly or bolt across a fence line onto adjacent property with a “No Hunting or Trespassing” sign. It can be frustrating..

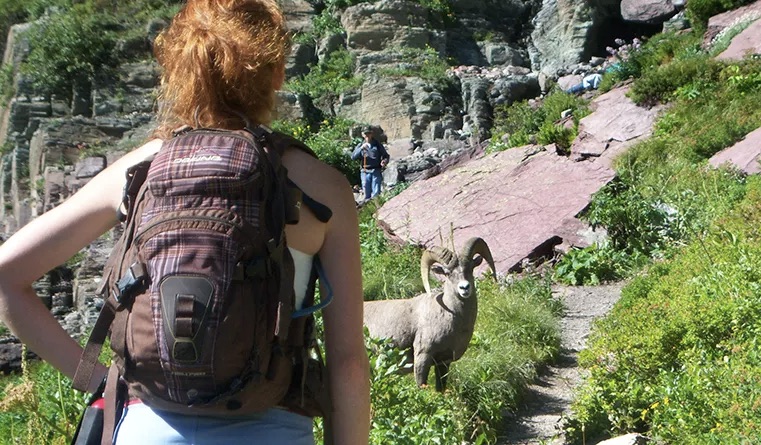

Equally frustrating is driving to a trailhead and seeing a full parking lot, or in the case of Block Management, sign-in boxes stuffed with more names of hunters than the number of live wild game birds on the property. The logical conclusion being advanced is: we need more access to more places.

At least that would be the conclusion if your primary interests were your own personal recreation and hunting pursuits. However, if your concerns also include the long-term well-being of wildlife and the character of wildlands, you might have a different perspective.

In the year 2024, many species of our most beloved wildlife are beleaguered, if not seriously threatened. How much more do the animals that make these places wild need to give up?

A Native American friend once told me that when his tribal council is discussing a resource management issue affecting wildlife, they leave an empty chair to remind themselves of the voiceless species that could be impacted by the council’s decisions. I wonder if organizations, like those who worked on the Gallatin Forest Partnership proposal for the Gallatin Range, made the long-term wellbeing of wildlife their top priority?

Even some once-common species, like the sharptail grouse, have been extirpated from many former haunts due to a variety of factors including habitat conversion, climate change, adjacent development, and cumulative human pressures. Overhunting, especially with efficient, topflight bird dogs, has also been a factor. This may sound heretical coming from a bird hunter, but maybe it’s not such a bad thing that there are posted properties scattered amongst the accessible units where heavily-pursued game can take refuge. It’s at least something to ponder.

On public land, there seems to be a full-court-press of efforts to fight conservation-oriented land management designations like Wilderness, which among its virtues limits volumes of cumulative human pressures and, as a result, benefits sensitive species over the long term.

Vocal efforts to limit new Wilderness designations are mainly spearheaded not by timber or mining interests, but by various recreation groups that do not like restrictions on, for example, mountain bikes or off-road vehicles. The current battle over Wilderness designation in the Gallatin Range is a case in point. The Gallatins run from Yellowstone National Park on the south to the back doorstep of bustling Bozeman. Rather than protect the Gallatins and its truly world-class concentration of wildlife, and employing the most effective land designation available, some groups are putting the self interests of outdoor recreationists first.

Vocal efforts to limit new Wilderness designations are mainly spearheaded not by timber or mining interests, but by various recreation groups that do not like restrictions on, for example, mountain bikes or off-road vehicles. The current battle over Wilderness designation in the Gallatin Range, which runs from Yellowstone National Park on the south to the back doorstep of bustling Bozeman, is a case in point.

Even river paddlers have tried to expand access at the expense of wildlife conservation, making runs at opening Yellowstone National Park’s protected waterways to boaters. Can you imagine driving all the way to Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley, and instead of gazing upon an almost Pleistocene-like landscape or listening quietly to wolves howling along the roadside, you are confronted by a parade of brightly colored rafts and kayaks filled with hootin’ and hollerin’ boaters?

A Native American friend once told me that when his tribal council is discussing a resource management issue affecting wildlife, they leave an empty chair to remind themselves of the voiceless species that could be impacted by the council’s decisions. I wonder if organizations, like those who worked on the Gallatin Forest Partnership proposal for the Gallatin Range, made the long-term wellbeing of wildlife their top priority, or a priority at all? My sense is that there was not an empty chair at their negotiation sessions.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying we should stop being vigilant about making sure access to public and private lands is maintained and, where appropriate, expanded. What I am saying is that none of our truly wild landscapes that miraculously remain today are—to use a bureaucratic terms often invoked by federal land managers—”underutilized.” As is, they are critical wildlife habitat, essential intact watersheds, and rare, living laboratories that can serve as baselines for measuring how the rest of our more compromised landscapes are being impacted by development. And, they are finite.

When it comes to reducing the negative effects of environmentally-damaging global phenomenon like climate change, the reality is there’s not that much we can do to reduce these impacts in the short term. But one thing we can do is avoid adding additional stress to these already-besieged natural systems.

I wish that access proponents thoroughly understood and incorporated wildlife conservation concerns into their access proposals and acknowledged their impacts upfront. And more than that, I wish they would only propose expanded access only if it is deemed to have negligible long-term impacts on wildlife and wildland values.

There aren’t many communities in the world with a higher percentage of Patagonia-wearing, conservation-group-membership-card-carrying citizens (many driving vehicles with wildlife-related license plates) than right here in Bozeman, Montana. Superficially, anyway, it seems like an extremely environmentally aware city.

Regardless of who wins the elections this fall, chances are that efforts to expand access to public and private lands will continue, if not increase. As locals in Greater Yellowstone and throughout the rural West, we can—and should—be monitoring these efforts and making certain that they do not come at the expense of our priceless wildlife heritage.

Will we, who say we value wildlife, rise to the occasion? Will a concern for wildlife and wild places override our personal desires for more recreational access? Will we, in fact, be that shining example of communities that, when it comes to conserving their natural environments, not only talks the talk, but also walks the walk? We shall see.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay appeared originally in the autumn 2024 issue of Outside Bozeman magazine, which you can find on newsstands throughout southwest Montana. You can also enjoy its great content by clicking here. Thanks to Outside Bozeman founder Mike England and writer Dennis Glick for granting us permission to reprint. If you have comments about Glick’s piece you would like to share, email them to us here. Keep them civil, thoughtful and on-point and we may print them below.

ALSO READ:

Of Wildlife, Wheels and Keeping Lands Wild by Calvin Servheen

Greater Yellowstone Coalition Plan For Gallatin Range Draws Flack From Many Of Its Alumni

If you’re in the Northern Rockies, love wild country and are fascinated by two of the region’s wildest icons, you’re invited to a pair of free public events in Bozeman and Missoula. They feature two of the premier bear and wolf experts in America. Hope to see you. Please let your friends know, too.