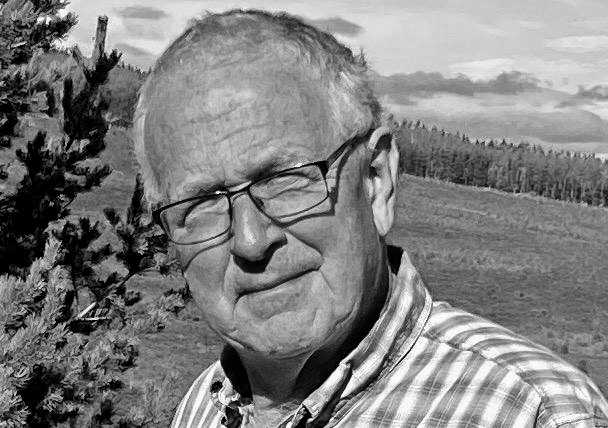

by Todd Wilkinson

To put it mildy, it’s “gettin’ Western” in America today and no more so than the region in which the expression was coined. (If you’re unfamiliar with the term, ask a cowboy to explain it in colorful detail). For writer, history buff, cultural observer and thought leader Sam Western, there ought to be an apt parallel that applies to his fearless knack of trying to make sense of abstruse social forces shaping our culture and landscapes.

Western is author of The Spirit of 1889: Restoring the Lost Promise of the High Plains and Northern Rockies that couldn’t be a better fit for this moment. He is giving a public reading at 7 pm Thursday in Livingston, Montana at the great indie hub, Elk River Books. Based in Sheridan, Wyoming, he was for 25 years a correspondent for The Economist magazine and in recent years when he isn’t writing books, has had different kinds of research jobs.

His take on the inner West stretching from the Rockies to the prairies of the Dakotas, Nebraska and Kansas has always been insightful. It stands in sharp contrast to the narratives invented by Hollywood and pulp fiction novels. In terms of original voice, it’s right up there with Wallace Stegner, Don Snow, Patty Limerick and Terry Tempest Williams.

Back in 2002, Western had his book Pushed Off the Mountain Sold Down the River published and it is, in its own way, an unflinching cult classic that, with a slight current of underlying snark, critiqued the portrayal of his home state, Wyoming, as a land of maverick, fiercely-independent cowboys and where the skies are not cloudy all day. The slim volume is a rip snorter, emerging around the time that Wyoming, as the largest producer of lower-sulfur coal in America and carrying a swagger with a gigantic budget surplus, was about to deal with a staggering reversal of fortune.

In the years that followed, a number of governors defiantly vowed in their state of the state addresses and other forums that they were “doubling down” on coal production as market forces were turning against Wyoming’s confidence it would never again undergo another boom and bust. Yet Wyoming’s coal economy, accompanied by bankruptcies and hardships of differing coal producers, was done in not by environmentalists but fracking and the new abundance of natural gas.

In his new book, Western guides readers forward from the time when five states (the Dakotas, Wyoming, Montana and Idaho) were still territories and they needed people and viable economies to be granted statehood by Congress. All kinds of special interests were at work behind the scenes, including wealthy outside investors who treated the interior West as a vast natural resource colony there to be exploited.

The Spirit of 1889 is part celebration of a nascent regional identity that held promise for having a more open society that valued individual thinking, the power of an educated citizenry and pushed back against exploitation by corporate monopolies. But as time has demonstrated, it did not last. Western explores the reasons why in his examination, and potential remedies emerge for how we, today, might move past this era of polemical tribalism.

Recently, Western and I discussed parts of his book, which is highly recommended and available from your favorite local booksellers and elsewhere.

Todd Wilkinson: 1889 is a pivotal year in the West when five new states were born and springing forth from them were separate administrative identities that came replete with mottos, provincial flags and “cultures” that while venerated as eternal are actually superficially constructed given the short of amount of time that has passed since settlers arrived. Set against the backdrop of geological, geographic, natural and indigenous histories, why is understanding the above so important?

Sam Western I’m not sure we can compare the narratives of the natural and political world. They operate on radically different time schedules. Yet, we need values – the roots of political beliefs and ideologies – that understand we have to live in harmony with the natural world. That’s a loaded—and obvious—statement, I know. In 1889, we were concerned with conquest as opposed to conservation, let alone harmony. We paid a price for that. But that’s what happens when you put both your economic and social identity in the commodity production basket. In the end, we need a value system that supports Aldo Leopold’s idea of a land ethic, “an individual responsibility for the health of the land.”

TW: The subtitle of your excellent book is “Restoring the Lost Promise of the High Plains and Northern Rockies.” What do you mean by that?

WESTERN: I draw a direct connection between economic and personal freedoms, including freedom of conscience. The 1889 constitutions embraced this notion, which actually were in place during territorial times. The Dakotas, ND, SD, MT, WY and ID encouraged the unconventional citizen: Hutterites, Mennonites and Mormons (although they had a rough go in Idaho for a spell). Look how they’ve prospered. Some faltered, like the Church Universal and Triumphant commune north of Yellowstone or the Jewish colonies in the Dakotas. They were generally peaceful and didn’t expect the rest of the society to follow their norms. Not everyone was included; Native Americans got totally screwed. Circa 2025, some regions, like western Montana and northern Idaho are home to the sovereign citizen ilk. They have singular political expectations that society will conform or at least oblige them. Yes, since territorial days, we’ve had vigilantes, but these folks are different.

Secondly, when I was writing Pushed Off the Mountain, I took a deep dive into the homesteader narrative.

Godallmighty, Todd. What heartbreak. Wallace Stegner refused to visit his family’s homestead on the Montana/Saskatchewan border. Too painful. Still, I think we can play that optimism/promise forward by supporting small agriculture. This is a big and complicated ask. Has to be ground up, like what folks have done in Winnett, Montana. The USDA needs a shake up on how to distribute the taxpayer dollar.

TW: An intriguing fact for reflection in these times is that Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, despite the ferocious pushback on affirmative action today, were actually ahead of other states in advancing women’s rights. There was this premise that our evolutionary thinking moves progressively forward, from new plateau to new plateau, and never do we backslide, be it with equal rights and respect for others, or in our dealing with carnivorous wildlife. What happened?

WESTERN: Social backsliding and nostalgic yearning for the days of yore are part of the human condition. Yet one of my favorite economists, Paul Samuelsen, said, “funeral by funeral, new ideas advance.” We can’t hide from the fact that women are kicking ass; society has mostly accepted this development. And but for a minority of hardcore Republicans, our nation has accepted gay rights. Look at the backlash against that Wyoming hunter who ran down a wolf with his snowmobile then tortured him. If this were the 1950s, Cody Roberts would be feted and given free drinks for a lifetime.

TW: You are not going to praise yourself, Sam, but I will praise you here, for over the last several decades courageously untangling mythology and assumptions often based on false assertions that are the basis of sometimes really misdirected public policy. Your reporting for The Economist was outstanding, even though the magazine doesn’t bestow personal bylines. You’ve been a thinker and writer constantly ahead of the zeitgeist. How has that been for you?

WESTERN: Thanks for your kind words. Pushed Off the Mountain kinda took Wyoming by storm. Totally unexpected, Todd. My publisher said we’d never sell more than one thousand copies. The book is now on its seventh edition and sold over 18,000 copies, I think. I chalk this mostly up to timing. By many economic and demographic metrics, late 1990s Wyoming was hurting. People wanted to know why. I got pushback and a little hate mail, but also support. About two weeks after the book was published I got a call from a trustee at the University of Wyoming. “Somebody,” he said, “had to write this book. Thank you.”

I wrote Pushed Off the Mountain in four months. The Spirit of 1889 took six years. Its premise goes against the current political grain. The response has been more muted, although I’ve had considerable interest from scholars and especially lawyers interested in the power of state constitutions.

I don’t write these books to obtain society’s praise, although it’s nice to get it once in a while. It’s how I participate in this world. Writing about macro issues or what Toynbee called the “deeper, slower movements” has its own rewards.

TW: I love Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, the states which converge to form Greater Yellowsttone. They are filled with good, hard-working people. Some of the best conversations I’ve ever had have involved one on one chats with rural people about life. And those conversations are far different than the kind of polemical ideological-driven tripe that spills out across AM radio airwaves. What do people dwelling in the larger and more prosperous mountain towns/cities need to better appreciate about rural folk?

WESTERN: Oh what a great – and essential – question. Really complicated, however. Rural America is convinced that society’s institutions are stacked against them. Commodity producers, especially agriculture, feel regulated to death. Great enmity towards those promoting those regulations: EPA, USDA, BLM, etc. Yet like any good trial lawyer will tell you, it’s not what’s true, it’s what the jury perceives to be true. How do we convince those good, hard-working people that those institutions work for their benefit? No easy task.

More importantly, it’s through those one-on-one conversations that we reach some sort of consensus. Spencer Beebee once told me a story of how a well-funded campaign to protect Willapa Bay from pollution fell on its ass. His takeaway? Not enough boots on the ground. “We didn’t go from oyster bed to oyster bed, talking to owners. There is no change without that action.”