By Phil Knight

In the Northern Rocky Mountains, there’s a great rugged land where wild lives play out against a backdrop of mind blowing mountains. Rising in a riotous mass of sharp peaks, craggy ridges and vast alpine plateaus, split by steep canyons, decorated with clear, cold tarns, draped with snow drifts, clad with vibrant evergreen forests, humming with creeks and waterfalls, and thrumming with wildlife, this landscape on the doorstep of Yellowstone National Park is a bastion of the untamed Earth.

Named for Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury, and James Madison, Secretary of State, two magical mountain ranges beckon beyond Bozeman’s ever more urban borders like some Rocky Mountain Shangri-La. The corrugated ranges and their lush surroundings teem with wildlife, with nearly all species present when these names were imposed on the Missouri’s headwater rivers by Lewis and Clark.

From the towering Hyalite Peaks near Bozeman to the Madison River Valley, the verdant and diverse Gallatin Range forms the spine of an unbroken 525,000 acre roadless wildland, unsurpassed in rugged beauty and teeming with native fish and wildlife. This range stretches far into Yellowstone’s remote Northwest corner, where Electric Peak reigns over the Gardiner Basin; Three Rivers Peak births the Madison, Gallatin and Gardner rivers; Antler Peak rises like an ancient pyramid above Swan Lake Flat; Fawn Pass draws backcountry travelers seeking to cross the mountains; Windy Pass beckons with endless alpine meadows; Eaglehead and Ramshorn Peaks bristle with Eocene petrified tree stumps; Mount Holmes keeps strange scimitars of snow on its north ridges well into summer; and the upper Gallatin River sings a wild song of grizzlies, trout and horse-mounted travelers.

Just across the Gallatin River to the west rise the higher, craggier Madisons, whose 11,000-foot glacial horns scrape the sky in serrated glory. Lone Mountain, the Sphinx, Gallatin Peak, Koch Peak, Echo Peak and the lord of them all, Hilgard Peak, offer an irresistible mountain paradise for all lovers of the high country.

Here you will find both colorful limestone peaks and brooding dark metamorphic peaks, all jumbled together and strewn with alpine tarns and waterfalls and draped with swathes of tundra. Remote refuges such as Hilgard Basin, Taylor Fork and Alp Creek shelter solitude-seeking moose, grizzlies, wolves and wolverines, while mountain goats and bighorn sheep skitter along ledges and ridges higher yet.

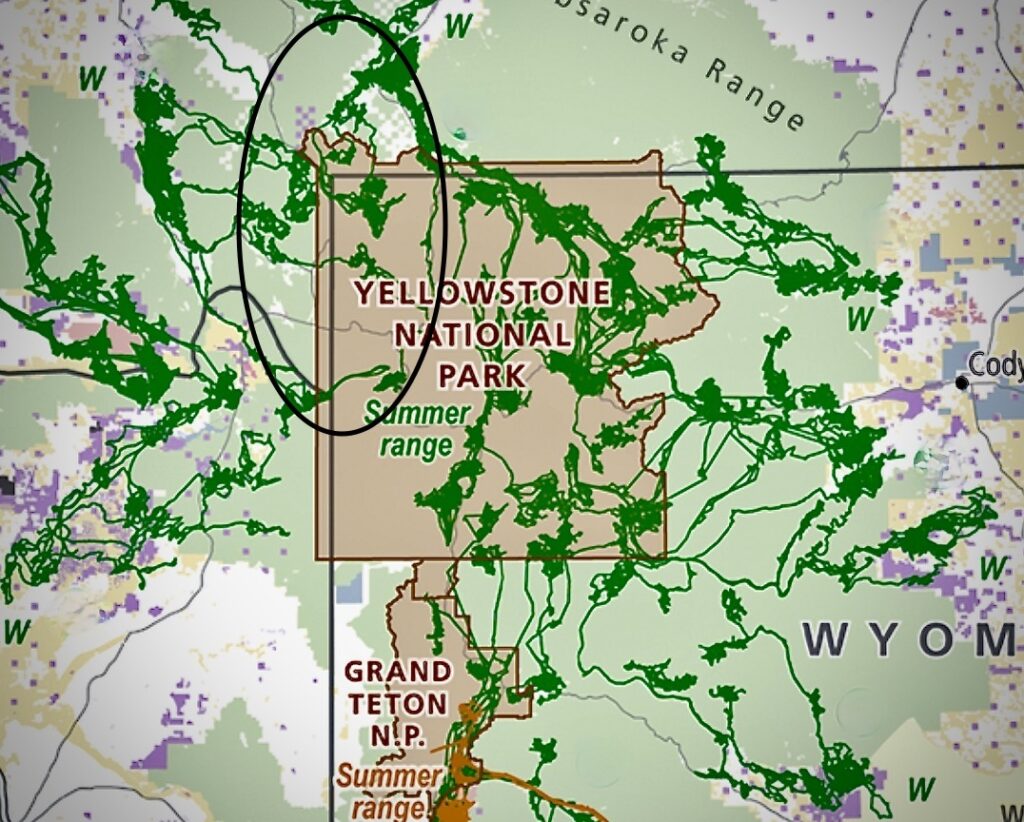

The Gallatin and Madison ranges are critical habitat for grizzly bears and all wilderness-dependent species in Greater Yellowstone, including bighorn sheep, mountain goat, elk, wolverine, wolf, and cougar. Some of the last best habitat for grizzly bears is found in the canyons and meadows of this paradise, and the threatened lynx may still survive in this rugged land. The mountain valleys contain essential wintering and birthing grounds for some of the nation’s largest elk herds. Twenty-three plant and animals species listed as threatened, endangered or sensitive exist here. The Gallatins are also part of an essential wildlife corridor linking the Yellowstone region with the Northern Continental Divide ecosystem and points north to the Yukon.

The Gallatin and Madison range vegetation mosaics are rich and diverse: a complex of Douglas-fir, aspen, and foothills prairie grace the lower elevations, with scattered juniper and limber pine. Higher up, aspen and Douglas fir are replaced by lodgepole pine, Englemann spruce and subalpine fir, mixed with rich mountain meadows. Near treeline, threatened whitebark pine becomes dominant on many sites, and well-developed alpine tundra characterizes the areas above 9,500 feet.

The 25,980-acre Gallatin Petrified Forest is a geologic marvel found close to and within Yellowstone’s northwestern corner. This is the world’s most extensive fossil forest, with 30 million year old stumps buried by Eocene lava flows, still anchored and upright atop these wild ridges. On the west side of the range, Madison limestone outcrops provide a stunning backdrop to the blue-ribbon fishery of the Gallatin River.

Human history goes back at least eleven thousand years in the Gallatins and Madisons. Native Americans visited these mountains to hunt bighorn sheep and elk and to harvest obsidian and chert for making stone tools, leaving evidence in the form of lithic points and rock chips. Shelters built by Sheepeater Indians may yet exist in remote drainages. These lands remain important to many tribes in the region, who visit them on a regular basis. The Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery traveled just north of the Gallatin Range when Clark led a return party over Bozeman Pass in 1806.

Divide Up In Order To Conquer

Controversy has dogged the fate of and status of the landscape on the northwest borderlands of Yellowstone for over a century, since the land was parceled out in the 1880s in square mile sections with every other section given to the Northern Pacific Railroad. The square mile grid pattern is the antithesis of the wild, imposing a harsh regime on a place with no boundaries. While much of the “checkerboard” grid has been resolved through costly land swaps, modern disagreements revolve around preservation vs. exploitation vs. recreation.

The Madison Range shelters the Lee Metcalf Wilderness, declared by Congress in 1983 and divided into four units. The Lee Metcalf Wilderness is broken into four segments: Spanish Peaks on the north, Monument Mountain on the east, Taylor-Hilgards in the highest and most remote portion, and the lower elevation Beartrap Canyon along the iconic Madison River. The legislation also created the Cabin Creek Wildlife Management Area where motorized recreation is allowed but resource development is outlawed.

The Gallatin Range, however, hangs in a seeming perpetual limbo with the wildest core of the range tentatively protected as the Hyalite-Porcupine-Buffalo Horn Wilderness Study Area, 155,000 acres sprawling across the highest ridges and down into the Hyalite Canyon and Porcupine/Buffalo Horn creeks. The entire Gallatin Range roadless area, encompassing more than 230,000 acres outside Yellowstone, deserves Wilderness status. This should be a new crown jewel of our nation’s Wilderness Preservation System.

The Gallatin Range hangs in a seeming perpetual limbo with the wildest core of the range tentatively protected as the Hyalite-Porcupine-Buffalo Horn Wilderness Study Area—155,000 acres sprawling across the highest ridges and down into the Hyalite Canyon and Porcupine/Buffalo Horn creeks. The entire Gallatin Range roadless area, encompassing more than 230,000 acres outside Yellowstone, deserves Wilderness status. This should be a new crown jewel of our nation’s Wilderness Preservation System.

A frenzy of logging and road building on national forests after World War II resulted in an overbuilt road network in much of the Gallatin Range and in parts of the Madisons and a pauperized forest of younger growth slowly reclaiming hundreds of clearcuts. Hundreds of miles of useless old logging roads remain, crumbling and sliding into creeks. Some roads have recently been ripped and reclaimed, with a resultant surge in wildlife activity.

Intensive logging has returned with a vengeance in last four years in the northern Gallatin Range under the guise of forest fire prevention and “forest health.” The Forest Service and the City of Bozeman have pushed through a stealth logging project, targeting 150 to 200 year old trees to sell to the sawmill while claiming they are protecting the Bozeman city watershed.

What Kind Of Fate For Yellowstone’s Essential Borderlands, Especially For Wildlife In The Face Of Growing Pressure?

Plans and visions for the future of the Gallatins and Madisons are a simmering mess. Everyone who knows the place has a plan for it, a way they want to use it and a strong opinion. This public passion for the Gallatin and Madison ranges speaks of the powerful feelings people have for this place and the depth of experiences people enjoy who visit the backcountry of Yellowstone’s borderlands.

Over it all hangs the spectre of Republican Party plans to give federal lands to the states which would open a massive sell-off a public lands to greedy rich investors. Even without the sell-off Republicans oppose any and all land protection measures such as WSAs and designated Wilderness. With Republicans soon wielding a stranglehold on the US government and the extremist Trump at the helm, the immediate future is grim for our last wild lands.

Current designations and proposals for the Gallatins and Madisons include the following:

-The Custer Gallatin National Forest’s Land Management Plan, completed in 2022, recommended some small wilderness areas in the heart of the Gallatin Range. Only about 70,600 acres of the WSA were recommended for wilderness (less than half of the 155,000 acres), along with about 15,000 acres of recommended wilderness in the steep, inaccessible Sawtooth ridge and a very welcome recommendation for about 17,000 acres in the Cowboy Heaven area of the Madison Range.

° ° ° °

–The Gallatin Forest Partnership’s controversial Greater Yellowstone Conservation and Recreation Act would create a slightly larger wilderness area in the Gallatins at about 90,000 acres while rebranding parts of the WSA as “Watershed Protection and Recreation Area” and “Wildlife and Recreation Management Areas.” It would also add some acreage to the Lee Metcalf Wilderness.

° ° ° °

-The Alliance for the Wild Rockies and its partners’ long-running Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act (currently in Congress) would grant full wilderness protection for the roadless lands of the Gallatins and Madisons.

° ° ° °

–The Gallatin Yellowstone Wilderness Alliance’s Gallatin Yellowstone Wilderness Act would designate as wilderness all of the roadless national forest lands of the Gallatins and Madisons.

° ° ° °

–Bold Visions Conservation’s 1.7 million acre Madison Gallatin Wildlife National Monument, the first proposed national monument dedicated to wildlife preservation, would outlaw hunting of predators such as wolves and bears and ban all trapping of wildlife. This bill is the first with major support from the Rocky Mountain Tribal Elders Council. It would manage the lands according to IUCN standards.

° ° ° °

Some political and recreational interests would strip all wilderness protection from the Gallatin Range and add no more to the Madisons, seeking access for unrestricted motorized recreation, logging, and other abuses. No doubt they will have plenty of sympathetic ears in the “Drill Baby Drill” Trump administration.

The states of Montana and Wyoming, meanwhile, are as anti-wilderness and wildlife as they can be, with state legislatures passing ever more draconian wildlife killing legislation and politicians running roughshod over wildlife professional managers, dictating policy with little science but lots of redneck attitude. Montana senators would strip all protection from the state’s wilderness study areas.

It may be hard to believe, but so called conservation groups pushing the Greater Yellowstone Recreation and Conservation Act (Greater Yellowstone Coalition, The Wilderness Society and Wild Montana) would divide up the Wilderness Study Area, leaving just the highest and most severe alpine area as wilderness and allocating the better habitat in Porcupine and Buffalo Horn Creek to the funhogs with their dirt bikes, snowmobiles, mountain bikes and snow motorcycles.

Turning loose the machines and riders not only allows further trampling, erosion and noise pollution, it also allows slob hunters to drive in to set their traps and snares and baits, bringing terror and death to the furry and fanged critters like bear, wolves, coyotes, mountain lions and bobcats.

Severing the Madison Range in an ever-expanding insult are the mega-sprawl resort developments of Big Sky, Spanish Peaks, and Yellowstone Club with uber-expensive hotels like the Montage and the One and Only, as well us luxury homes and a major growing townsite sprawled all across the West Fork Gallatin River.

Is this really the highest and best use of this phenomenal landscape? An ever growing, metastasizing sprawl of trophy castles and 8-person heated high speed ski lifts? Will $15 cappucinos become more common than wild animals or living whitebark pines?

Let’s see if we can’t abide some limits on our own activities and set aside what still remains wild. Let’s practice some self-restraint and recognize that here we still can experience a truly wild and self-regulating ecosystem. Let’s look beyond the constant craving for Instagram-worthy wheeled motorized excitement and step back for a moment. Hear that wind in the pines? That cackle of ravens playing on the wind? That piercing bugle of the bull elk in rut? That haunting howl of the grey wolf? That is the real, wild world calling. Listen, and take a stand for the land.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Yellowstonian thanks Phil Knight for penning this essay. In full disclosure, Mr. Knight is an advocate for passage of Bold Visions Conservation’s proposal for a Gallatin Madison National Monument. While Yellowstonian believes that the Gallatin Range needs protection in order to safeguard its world-class wildlife against intensifying human pressures—and based on a compelling argument grounded in science— we do not advocate for a particular proposal to accomplish that. To understand more about the pressures, read:

Wreckreation And Our National Obsession To Love Wild Places To Death

Subdivisons: As Impactful To Wildlife Over Time As Clearcuts, Mines And Energy Combined

What Happens When Greater Yellowstone’s Conservation Movement Goes MIA On Sprawl?

The Spillover Effects Of Big Sky’s Ravenous Appetite For More

Meet The Real Madison—And Why It’s Called ‘A Mini-American Serengeti’

A Yellowstonian Exclusive: Watch The Documentary ‘Subdivide And Conquer: A Modern Western,’ For Free

Proposed Suce Creek Luxury Resort In Park County Is Just “Tip Of The Iceberg”

New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife