EDITOR’S NOTE: Think of how we orient ourselves to personal geography, how we create our world views based on those coordinates. From US Interstate 80 in southwestern Wyoming,where the story below begins, you’re 200 miles (equidistant to downtown Salt Lake City in one direction or to the Town Square of Jackson, Wyoming in another); 415 miles (or about seven hours by car) away from Bozeman, Montana. Now imagine that you and perhaps a few friends are mule deer, and you’re moving, not out of fun but it’s what keeps you alive. Your persistence depends on you successfully navigating a perilous gauntlet of human and natural obstacles and doing it to and fro year after year in good weather and bad. In this enlightening story written by Dr. Matt Kauffman, chief scientist with the Wyoming Migration Initiative and science writer Emily Reed, they describe a journey that will take your breath away, and help you come to better appreciate why the still-intact pathways of wildlife in Greater Yellowstone are fragile and sensitive wonders of nature. Lose them and you lose the spirit of an ecoregion. The essay that follows is an excerpt from a new book, A Watershed Moment: The American West in the Age of Limits which we strongly recommend you read as you ponder your own navigations of this ecosystem and the rest of the West. —Todd Wilkinson

by Emily Reed and Matthew Kauffman

The small town of Superior, Wyoming, used to be a booming coal town. Pictures from the 1920s reveal sparkling new cars, a bowling alley, and other amenities supported by the wealth of the coal mines. Today, those prosperous days are nowhere to be seen. Superior doesn’t have a grocery store or a gas station, and the local bar is only open occasionally. Aside from the low-slung, modest houses built into the hills around town, the most prominent structure is the county road maintenance shop.

But those hills are also dotted with mule deer—lots of them. Superior represents the southern terminus of the world’s longest-recorded mule deer migration and it’s located in the southern-most reaches of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

The study of these deer has shaped how wildlife biologists think about migration, and the conservation of their corridor illustrates how science informs the management of iconic Western wildlife populations. These deer, and their story, may also represent what is possible when we recognize the habitat needs of wildlife that move across the same landscapes where we live and work.

How The World’s Longest Mule Deer Migration Became Uninvisible

This corner of the Red Desert outside of Superior is a great place for mule deer to spend the winter. Aside from the one paved road that runs from town to Interstate 80, seven miles to the south, most other roads are two-tracks that are largely impassible once the snow arrives and the near-constant wind hardens it into drifts. Except for the few hundred hearty humans that live here, and the occasional oil and gas truck checking on some gas wells to the west, the deer have most of the area to themselves.

While this country is quite dry, the draws hold sufficient moisture to grow robust sagebrush and the forage that comes with it. Perhaps what is most important is that this country is mostly free from the ravages of the deep snow that piles up along the foothills of Wyoming’s mountain ranges.

It’s clear that some of Wyoming’s migratory routes are still intact today because of the open space, but we know that they are still vulnerable, especially in today’s modern world. Similar to the Western “boomtowns” brought about by oil and gas, there are now “zoom towns,” where remote workers are moving to Western gateway communities and building houses, some of which are in crucial winter range areas for wildlife.

The mule deer are not full-time residents. To appreciate their movement, it’s important to consider topography and terrain. Once the days lengthen and the snow begins to melt, they turn their noses north toward the Wind River Range, where there is the promise of abundant spring forage. Sometime in April or May, depending on the snow conditions, they cease the roundabout movement on their small winter ranges, straighten out their trajectory, and begin moving north. For the first thirty to forty miles, they move through the sagebrush habitats of the Red Desert, skirting the Killpecker Sand Dunes to climb up and over Steamboat Mountain, where some stop over briefly to forage before heading on. Then they head up to the northern end of the Red Desert, crossing State Highway 28. After crossing the highway, they take a northwesterly bearing along the western foothills of the Winds.

The herd moves along the foothills, many of which are working lands used primarily for livestock grazing and mineral extraction. Such lands underpin many ungulate migrations in Wyoming, which are far too vast to be contained within the region’s protected areas. Here the mule deer move across a mix of private lands, federal lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and US Forest Service, and a few state of Wyoming parcels. This wide-open rangeland tends to support migrations of deer, elk, and pronghorn as long as they can jump or slip under the livestock fences. The ranch houses are few and far apart—even so, the migrating deer hug the mountains, giving them a wide berth. After moving about forty miles along the foothills, the herd comes to Boulder Lake, its outlet stream swollen with the snowmelt. The larger does can ford the stream, hooves stable on the rocks below, while the fawns must swim. But most make it safely across.

After Boulder Lake, the corridor starts to become busier with human activity. Another five to seven miles and the deer will no doubt see the lights and hear the vehicle noise of Pinedale, the biggest town in the Upper Green River Basin. Fueled by an oil and gas boom in the early 2000s, Pinedale and its surroundings have grown over the years. Its subdivisions are pushing up against the foothills and Fremont Lake, which juts out like a finger from town, heading northeast deep into the flanks of the Wind River Range. As the deer approach the lake, they have limited options.

As the deer approach the lake, they have limited options. The path around the lake to the right is blocked by the steep mountains, and it would be a long swim to go straight across. The best choice for the migrating deer, it seems, is to cross near a narrow outlet of the lake where it funnels into Pine Creek, which runs down into town.

This choice requires the deer to navigate through an obstacle course of challenges. If they cross below the lake with a simple traverse of Pine Creek, they end up on the wrong side of an eight-foot-high woven-wire fence constructed to prevent elk from spilling onto private lands. They can stay above the fence, but that requires them to swim the tail end of the lake before it funnels into the creek. Every year biologists recover carcasses of deer that failed to navigate the iced-over portion of the lake in spring.

These decisions are further complicated by activity from a marina, a restaurant, and a lodge located near the bottleneck. They have now come nearly a hundred miles, having left winter range a few weeks before, and the abundant forage they seek lies beyond this human-made bottleneck. They still have a long way yet to go.

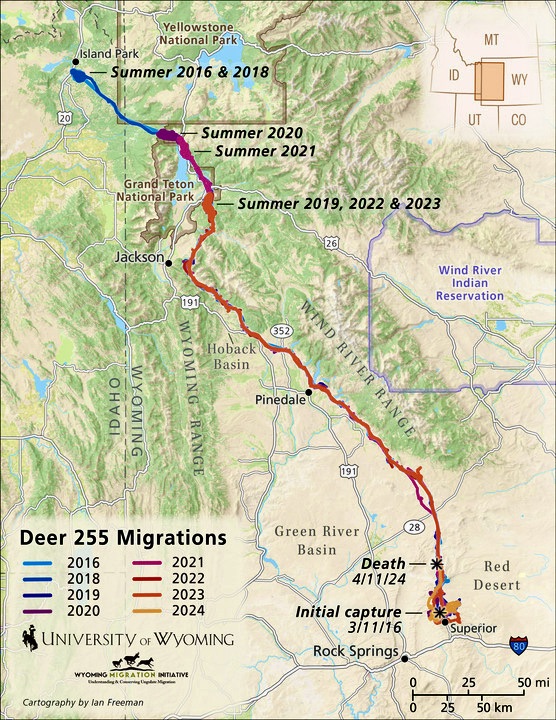

Putting Epic Migrations On Maps

The migrations of these deer weren’t always known, at least not the full expanse of their movements from one end of the corridor to the other. In 2011, wildlife biologist Hall Sawyer captured and put collars on forty mule deer that were wintering down in the Red Desert near Superior. He had been funded by BLM to conduct a study to figure out the habits of deer who live “year-round” in the desert. Much to Sawyer’s surprise, he couldn’t find the collared deer in the Red Desert when he went to look for them during the first summer. Finally, he sent a plane in search of the radio frequencies the collars emitted. They started hearing the familiar “pings” from the collars once they got up near the Hoback Basin, the headwaters of the Hoback River. Once the collars dropped off and Sawyer could map all the locations, a picture emerged of a narrow corridor from a winter range in the Red Desert to summer ranges in the Hoback Basin—150 miles away. It was then the longest migration ever recorded for the species.

Charting it across a map of southwestern Wyoming, Sawyer and his colleagues at the University of Wyoming were amazed at the migration (see figure 17.1). The length was of course impressive, but they were more impressed by the country these deer traveled. As they migrated over just one spring or fall, they moved in and out of lands managed by two federal agencies and two state agencies, crossed ranches owned by about forty different private parties, and crossed three or four highways and about a hundred fences.

The researchers decided to do something that had never been done before for ungulate migrations in the American West—they conducted a “migration assessment” to identity obstacles.

Maps are a powerful means to convey conservation priorities, and the map of the corridor made it hard to mistake what a formidable challenge that bottleneck was. The sheer distance they travel before and after the bottleneck spoke to how important those movements must be.

Sawyer and colleagues also helped tell the story, with a glossy report, a short film, and a photo exhibit by wildlife photographer Joe Riis that toured around the state. Conservationists working in the region quickly became aware of the importance of Fremont Lake to the newly discovered migration. One of those was Luke Lynch, who worked to prevent development on private lands in the region primarily by purchasing conservation easements from willing landowners. When Luke learned that the 360-acre parcel at the outlet of the lake was up for sale and already drawn up for lakeside cottages, he saw an opportunity to conserve the parcel for the five thousand migrating deer that cross through it.

The tracked movements of the deer made it clear how important that bottleneck was to the migration, and that information combined with Luke’s tenacious fundraising quickly resulted in the necessary funds ($2.1 million) being raised to purchase the property outright. That deal was done in 2016, and the property was turned over to the Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD), which created the Luke Lynch Wildlife Habitat Management Area. The deer still move through that narrow spot each spring and fall, but the fences have been removed by volunteers working with Game and Fish, and the property is protected from further development in perpetuity.

Highway Crossing Structures And Their Role In Preserving Migrations

Not far from the Fremont Lake Bottleneck, about five miles west of the town of Pinedale, is an open ridge dotted with sagebrush, carved out by the Green River on one side and the New Fork River on the other. The area is known as Trappers Point, as it was a trading hub for hundreds of trappers and Native Americans in the 1830s and 1840s. Trappers Point is a natural bottleneck that acts as a one-mile-long gateway between the riparian zones of the Upper Green River Basin and the more mountainous sagebrush hills that lead into the Gros Ventre Range.

In the early days of spring, a group of about 350 pronghorn begin their 90-mile migration from their winter range in the Upper Green River Basin to their summer range in Grand Teton National Park. This pronghorn herd makes one of the longest wildlife migration in the Lower 48 states.

(Note to readers: learn also abut pronghorn and elk in Montana’s Madison Valley by clicking here).

Their journey is not an easy one: they must pass through the bottleneck at Trappers Point, which has now shrunk to be a half-mile wide because of recent housing developments. As they make their way through the open space that is left, they reach their first and perhaps most dangerous barrier along the route.

Running alongside Trappers Point, bisecting their migration, is US Highway 191, a busy two-lane roadway connecting Pinedale to Jackson Hole. In this exact spot, about five thousand years ago, early human hunters used the outlet of the bottleneck to ambush the pronghorn as they moved north. Archaeological evidence discovered in 1992, when a section of Highway 191 was widened, revealed one of the largest and oldest known pronghorn kill sites by early human hunters.

Before the pronghorn even reach Highway 191, they must make it through right-of-way fencing that encompasses both sides of the blacktop. Pronghorn, in particular, struggle with crossing fences, as they prefer to duck under the bottom wire rather than jumping. In years when there are heavy spring snowstorms, snow drifts impact their ability to find sections where they can slip under the wire. Weaving between the traffic on U.S. Highway 191 became more difficult for the herd as traffic increased during the years of Pinedale’s natural gas-fueled economic boom in the early 2000s. Nearby mule deer that spend their winters on the Mesa, an area just south of Trappers Point, also had to contend with the difficult crossing of US Highway 191. In the 2000s, wildlife-vehicle collisions became increasingly common, with about eighty-five incidents occurring annually.

The pronghorn and mule deer who survived the crossing of US Highway 191 would continue their migration. The mule deer settle into their summer ranges in the Upper Hoback Basin and the northern end of the Wyoming Range, but the pronghorn keep going. In 2008, the first 40 miles of this pronghorn migration from Grand Teton National Park through the Bridger-Teton National Forest was federally designated. As of this writing, it remains one of the only herds that has part of its migration federally designated as a wildlife corridor in the United States.

Around this same time, a pilot project had been completed in another part of Wyoming that would lay the groundwork for conserving this famous pronghorn herd and many others. About 100 miles southwest of Pinedale, near the town of Kemmerer, wildlife biologist Bill Rudd and Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) district engineer John Eddins had worked to install seven wildlife underpasses and seven miles of fencing in Nugget Canyon along US 30. The project was a success: wildlife-vehicle collisions declined significantly, and trail cameras in the tunnels recorded thousands of mule deer and even a few moose using the underpasses.

The success of Nugget Canyon propelled stakeholders back in Pinedale to think about implementing something similar. There was a looming question: Would migrating pronghorn use an overpass? With maps of migration and data on vehicle collisions in hand, a collaborative group of researchers, wildlife managers, and engineers designed a system of crossing infrastructure that included two 150-foot-wide overpasses, six underpasses, and thirty miles of fencing to help direct the animals.

Pronghorn survival hinges on their speed and keen eyesight, unlike mule deer. As a result, they tend to steer clear of dark and narrow spaces such as underpasses. The overpasses would be the first of their kind in Wyoming and the first ever built specifically for pronghorn in the world. The project was completed and open for ungulate use in 2012.

Conservationists, researchers, engineers, and local community members waited anxiously for fall migration to begin to see if the newly completed project would work. The project was a success, with 90 percent of pronghorn using the overpasses and 80 percent of mule deer using the underpasses, leading to an 80 percent reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions three years postconstruction. A lesser-known yet significant outcome of the project was the expansion of winter range usage by mule deer on the Mesa. The project received numerous awards, including the Wyoming Engineering Society’s 2012 President’s Project of the Year and the Federal Highway Administration’s 2011 Exemplary Ecosystem Initiative Award.

Conservationists, researchers, engineers, and local community members waited anxiously for fall migration to begin to see if the newly completed project would work. The project was a success, with 90 percent of pronghorn using the overpasses and 80 percent of mule deer using the underpasses, leading to an 80 percent reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions three years postconstruction.

Although the project came with a hefty $10 million price tag, it carried an impressive return on investment. Within twelve years, the project would pay for itself by reducing property damage resulting from wildlife-vehicle collisions, which on average costs $11,600 per incident.

Reducing wildlife-road conflicts has continued to be a priority in Wyoming. In 2017, 130 people from conservation nonprofits, wildlife agencies, and universities gathered with WYDOT engineers for the Wyoming Wildlife and Roadways Summit. They identified 240 stretches of roadway that were of special concern for wildlife mortality. Each section was then evaluated by crash frequency, core wildlife habitat, and migration corridors to identify the top ten most critical projects.

Two and a half years after the Wyoming Wildlife and Roadways Summit, the state secured more than $17 million for a project along Highway 189 between La Barge and Big Piney that included eight underpasses and additional fencing. A federal grant provided the initial $14.5 million, but WYDOT and Game and Fish both contributed $1.25 million.

Citizens of Wyoming have shown great support for these projects as well. According to a poll of four hundred registered Wyoming voters conducted by the University of Wyoming in 2019, 64 percent strongly supported constructing more crossings, while an additional 22 percent somewhat supported the initiative.

The poll also revealed that 76 percent of respondents viewed highways as a significant threat to wildlife migration. This percentage was higher than all other factors identified in the poll, including development, fencing, climate change, and oil and gas drilling. In the same year this poll was conducted, 79 percent of Teton County voters approved the allocation of $10 million in Special Project Excise Taxes (SPET) for wildlife crossing projects. Two wildlife crossing projects are funded through SPET and are expected to be completed by 2025.

In November of 2021, President Biden signed a $1 trillion infrastructure bill, with $350 million of that bill being earmarked for wildlife crossing infrastructure, the largest investment in wildlife crossings in national history. A few months later, in December of 2022, Wyoming’s Republican governor, Mark Gordon, set aside $10 million of the state’s $1 billion allocation of American Rescue Plan Act funding for wildlife crossing projects.

The appropriation of these funds will help support an overpass for wildlife on Interstate 80 near Elk Mountain between Laramie and Rawlins, improvements to wildlife fencing and a wildlife underpass along US Highway 189 near Kemmerer, and additional wildlife fences, three underpasses, and an overpass along US Highway 287 near Dubois. In December of 2023, Wyoming was awarded the largest federal grant ($24.3 million) from the US. Department of Transportation’s new Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program. The grant will build wildlife crossings for mule deer and pronghorn along a thirty-mile stretch of Highway 189 south of Kemmerer.

Despite its reputation as a fiscally conservative state, Wyoming has made significant financial investments in wildlife conservation. While we don’t have any data points or sophisticated analysis that identify the social dynamics that underscore the success of wildlife crossing conservation in Wyoming, we can speculate that it really boils down to the shared human-wildlife connection. For example, the partnership between WYDOT and Game and Fish can be traced back to the shared values of Eddins and Rudd’s love for mule deer on the landscape. One could pose the question, If a WYDOT engineer did not have a personal connection to migrating mule deer, would there have been such enthusiasm for a wildlife crossing project? A deep love and attachment to these animals within people who work in transportation agencies is the catalyst for this ongoing roadway conservation success story in Wyoming.

How Migration Maps Can Guide More Thoughtful Energy Development And Subdivisions

Wyoming has more mapped ungulate migrations than most other Western states, with much of that collaring work being conducted in response to ongoing oil and gas development. Many studies have been funded by the energy companies themselves, while other studies were funded by state or federal managers seeking to quantify the impacts or to collect wildlife information to guide adaptive management as gas fields were being built.

Several boom periods, starting in the 2000s, illustrated the potential for wildlife habitat to be transformed rapidly by oil and gas development. It is an unfortunate coincidence that many of the best places to drill for oil and gas in Wyoming also happen to be critical habitat for ungulates to winter or migrate through on their way between their summer and winter ranges. Consequently, there are now numerous development areas that overlap with key habitats for ungulates.

One such place is the Pinedale Anticline, where world-class energy resources (natural gas) coincide with world-class wildlife habitat: namely, the sheltered winter range for the Mesa mule deer. Biologist Hall Sawyer began monitoring mule deer movements during winter in this area shortly after the development began in early 2001, and it is one of the longest-running studies to evaluate impacts from oil and gas. The results are not terribly complicated or surprising. The deer, many of which are also migratory and summer in the Hoback Basin (sharing that range with the deer that come up from the Red Desert), come down out of the mountains in early winter to the Mesa winter range.

As construction began, a clear pattern emerged wherein the deer would spend less time around the well pads, especially when they were being actively drilled. During drilling, there is nearly constant truck traffic in and out of the area as the vehicles carry supplies, equipment, and laborers. The wintering deer give these areas a wide berth, much like other wildlife avoid areas with high human activity. It is a type of indirect habitat loss, and it can mean that mule deer miss out on the forage within and around the actual footprint of the human disturbance.

Sometimes development is permitted directly within a migration corridor. Researchers have wondered if mule deer would simply stop using those migration routes. A long-term study of the Baggs mule deer herd in south-central Wyoming has provided the clearest answers. The sagebrush basin around Baggs, Wyoming, winters approximately two to three thousand mule deer, most of which migrate in a northeasterly direction across Wyoming Highway 789 up into the Sierra Madre Range for summer.

The Atlantic Rim project began drilling wells for coal-bed methane in 2005, and about forty mule deer were collared on winter range at the same time. When the GPS data came back, it was immediately clear that the development area was right in the middle of a key migration corridor. A first set of studies showed a common behavioral response, where instead of avoiding human activity, the deer sped up as they moved through the well pads. The speeding up through the development came at a cost: the deer also reduced the area they used for stopovers by 60 percent.

One way to measure the “functionality” of a migration corridor is to evaluate how well animals pace their movements with the wave of spring green-up, which allows them to access fresh, green forage when it is most digestible. This behavior—the way that deer choreograph their movements in pace with their preferred forage—is known as “surfing the green wave.” In the case of the Atlantic Rim study, researchers were able to monitor the movements of mule deer throughout most of the period of gas field development.

In 2005, when there were just a few wells, the mule deer kept pace with the green wave (i.e., surfed) throughout their migration. But as early as 2008, they changed their behavior: they migrated off winter range and began to congregate in a large stopover just before the development area. Some deer spent weeks held up on the edge of the development before eventually rushing through it and continuing to their summer range. But the green wave didn’t stop.

As the deer were held up, the green wave passed them over, moving up in elevation following the snowmelt. The deer were now behind the green wave. There was evidence that deer moved more quickly after the development area to catch the wave, but the overall result was for deer to become increasingly mismatched over the period of the study from 2005 to 2018) Researchers estimate that their altered behavior in response to development caused mule deer to experience a 38 percent reduction in the foraging benefit of migration.

These studies, and others, have established that development reduces the functionality of migration corridors—such disturbances and barriers make it more difficult for ungulates to migrate, causing them to miss out on the foraging benefits of migration. Ungulate migrations have been lost around the world. When foraging benefits are lost, deer are expected to put on less fat, rendering them less capable of producing healthy fawns and reducing their chances of surviving the harsh winters in Wyoming.

In essence, a population that uses a heavily developed corridor can become what ecologists call a “sink habitat”—a habitat no longer able to support positive population growth. With fewer animals produced each year than are needed to replace those that die from natural causes, animals slowly drain out of the population and off the landscape. Because migration behavior takes many generations to be learned and transmitted throughout the population, lost migrations cannot easily be restored. For example, it took bighorn sheep about forty years and moose nearly ninety years to learn new migration routes after being translocated.

In essence, a population that uses a heavily developed corridor can become what ecologists call a “sink habitat”—a habitat no longer able to support positive population growth. With fewer animals produced each year than are needed to replace those that die from natural causes, animals slowly drain out of the population and off the landscape.

Most of this science was in place in 2018 when President Trump’s administration was strongly prioritizing oil and gas leasing on public lands. In its end-of-year lease sale, the BLM proposed to lease approximately a million acres in Wyoming. Dozens of those parcels overlapped the mapped corridor of the Sublette Herd, which contains the herd segment that makes the migration from Red Desert to Hoback. The proposed leases were in the BLM lands that are scattered throughout the Red Desert, the last leg of the journey the mule deer make down to winter range, between the southern tip of the Wind River Range and the town of Superior.

By this time, the state of Wyoming had become focused on corridor conservation. Following the mapping of the corridor in 2014, the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission passed an Ungulate Migration Corridor Strategy in 2016. The new policy provided a process for the Game and Fishto designate a migration corridor as a “vital habitat,” which they could seek to manage for no net loss of function . The Sublette mule deer corridor, including the Red Desert to Hoback segment, was officially designated later that same year.

Once the leases were mapped and the conflict with the corridor became clear, the letters poured in. A wide range of groups, including hunting groups like the Muley Fanatic Foundation, wrote to Game and Fish and Wyoming Governor Matt Mead, requesting the leases be deferred. Some of the most powerful voices came from the county commissioners of Teton County near the summer ranges, and most importantly, Sweetwater County, where the winter range is located. For their part, Game and Fish managers recognized the importance of the corridor, having been collaborators on most of the studies evaluating how gas development could diminish the functionality of the corridor.

Ultimately, then-WGFD director Scott Talbott and Governor Mead wrote a letter to then Department of the Interior secretary Ryan Zinke requesting that a small number of parcels—those that were 90 percent or more within the mapped corridor—be removed from the lease sale. In July 2018, Zinke and Mead announced the deferment of nearly five thousand acres of leases that overlapped the corridor and were deemed too much of a threat to its functionality. It is presumably the first time a mapped corridor has led to oil and gas leases being removed from a lease sale to make space for migrating ungulates. Through 2019, the BLM continued to remove proposed leases from sale lists so that approximately twenty-four thousand acres within the corridor are now protected from oil and gas development.

Ongoing Serious Challenges for Migration Conservation

The science of ungulate migration has developed quickly—and still is. In the political landscape, policies that preserve migratory corridors across public and private lands are complex and don’t offer complete protection. In 2020, Governor Gordon signed an executive order that replaced the 2016 Game and Fish Ungulate Migration Corridor Strategy. The executive order allows the agency to nominate new corridors for designation, to be reviewed by a local working group and approved or rejected by the governor.

The corridors that are approved for designation then receive some degree of protection: the state of Wyoming issues permits for a range of development types to reduce disruption to the corridor habitat. It also encourages private landowners to keep migration corridors and routes functional but does not mandate any management actions to do so. While conservationists appreciate that part of the new designation process includes multiple opportunities for public input, some feel that the designation process is simply too slow given the ongoing threats and expanding footprint of development of all types.

One of the candidate herds considered for designation is the Path of the Pronghorn, the corridor that received federal designation in 2008. The southern portions of the route that would be designated under the 2020 executive order are where the animals intersect with oil and gas fields.

One oil and gas field on BLM is being developed and is currently under litigation from environmental groups for impacting both sage grouse habitat and the pronghorn migration. BLM has already approved the gas field development, citing that the pronghorn migration route did not have any special designations in that area. Similarly, a state of Wyoming oil and gas lease was auctioned off and approved in an area that Game and Fish and conservation groups consider a bottleneck for the Path of the Pronghorn. Wildlife advocates have been vocal about the need to designate the entire Path of the Pronghorn corridor in a timely manner and ensure management of the corridor limits new oil and gas development. As of this writing, the Path of the Pronghorn is still not designated under Wyoming’s executive order.

Even though dozens of migrations have been mapped in Wyoming and some have been designated, they are often not included in more localized land use decisions on private lands. One recent example is in Sublette County, where there has previously been a lot of momentum around migration conservation. This county is where the Fremont Lake bottleneck and the Trappers Point road-crossing projects are located. In 2021 and 2022, commissioners approved a 56-acre zoning change that would allow a billionaire to build an exclusive retreat. They also rezoned 299 acres of former agricultural land so it could be developed into houses and approved the construction of a trauma therapy center—all within the Red Desert to Hoback migration corridor.

What underscores some of these zoning decisions is the pressure on the county to expand housing, the need for rural-based mental health care, the economic interest in resort tourism, and the revenues associated with expanded commercial and residential development. The ongoing struggle of agricultural producers in the area to make ends meet or recruit the next generation to take over the operation also adds pressure to develop.

Even though there is more federal funding available to support agricultural producers that are in big-game habitat areas through voluntary opportunities and incentive-based approaches such as habitat leasing and conservation easements, farms and ranches are still being developed at an alarming rate.

The ongoing struggle of agricultural producers in the area to make ends meet or recruit the next generation to take over the operation also adds pressure to develop. Even though there is more federal funding available to support agricultural producers that are in big-game habitat areas through voluntary opportunities and incentive-based approaches such as habitat leasing and conservation easements, farms and ranches are still being developed at an alarming rate.

It’s clear that some of Wyoming’s migratory routes are still intact today because of the open space, but we know that they are still vulnerable, especially in today’s modern world. Similar to the Western “boomtowns” brought about by oil and gas, there are now “zoom towns,” where remote workers are moving to Western gateway communities and building houses, some of which are in crucial winter range areas for wildlife. Green energy initiatives have led to solar panels and wind turbines being assembled across the prairie, sometimes within migration corridors or winter ranges of the state’s abundant ungulate herds. The reality is that without adequate protections for habitat, any type of development poses a threat to migrating wildlife populations.

Conserving wildlife while providing for the needs of a growing human population is possible—it is not an either-or proposition. But it will require more cooperation. Untangling how we can make these compromises in modern society across multiple scales will require us to prioritize the importance of understanding how to communicate better about what the science is telling us and to integrate that into communities for their knowledge and planning.

Many Wyomingites know about the Red Desert to Hoback migration, the Fremont Lake bottleneck, and the success of the overpasses that have allowed pronghorn to more easily navigate Trappers Point. It seems clear that local knowledge of these migrations, and the connection that people have to the herds, has underpinned and prompted these conservation actions. The influence of even a single connection to an animal or a species can have a profound effect on the hearts of decision-makers, potentially paving the way for viable and lasting solutions.

ALSO READ/VIEW:

Where Does The West Go From Here? New book, A Watershed Moment: The American West in the Age of Limits enlists incredible roster of writers to assess where we’re at. Yellowstonian interviews one of the editors, Robert Frodeman, about limits and how we decipher myth from reality. To learn more about the book and public forums with its authors, click here.

Goodbye Long Distance Traveler Mule Deer 255: Thanks For Everything You Taught Us This essay by Gregory Nickerson of the Wyoming Migration Initiative following the passing of Mule Deer 255 who a few years earlier was documented carrying out the longest known mule deer migration in modern times.

New Scientific Study Focuses On Largest Threat To Greater Yellowstone’s Iconic Wildlife Sprawl is happening everywhere but in the bioregion surrounding Yellowstone it is having huge impacts on a wildlife concentration unparalleled in the Lower 48 and renowned in the world.

Below, an interview about Greater Yellowstone wildlife migrations with Greg Nickerson of the Wyoming Migration Initiative and Jeff Reed of Paradise Valley, Montana with Todd Wilkinson was part of the 2024 Yellowstone Summit

Part One:

Part 2: